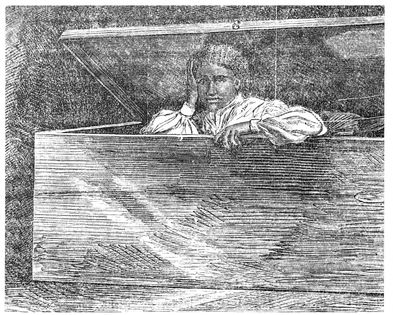

Maria Weems, disguised as a carriage driver

“Are you the passenger expected from Washington?”—William Still

Rockville, Maryland, to Ontario, Canada, 1855

In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act. The law said that anyone who helped a slave become free or hid a slave could be fined $1,000 or jailed for six months. Suddenly unsafe, thousands of slaves who had escaped to Northern states fled a second time to Canada. And slaves in Southern states now made Canada, a longer journey, their goal. The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society maintained a line of the Underground Railroad. Members raised money to buy slaves from their masters and also arranged for runaways to be conducted safely to Canada. Their leader was William Still, a free African American whose parents had been slaves. It was said that any runaway who could make it

to Still’s office in Philadelphia was as good as free. Hundreds arrived by foot, boat, and rail—and in one famous case, even in a box. Still kept detailed records of the hundreds of cases he handled. Maria Weems was one of his youngest passengers.

The year she turned twelve, Maria Weems was sold without warning from the plantation where she had grown up to a quick-tempered slave trader from Rockville, Maryland, named Charles M. Price. Her new home was hellish. Price drank heavily and turned violent when he got drunk. His wife was quick-tempered and rough, too.

Maria clashed with Price from the start. She had free relatives, some of whom had been bought and freed by abolitionists, others who had escaped. She was determined to be free and made no effort to hide her feelings from Price. Her fearless, independent spirit made him just as determined to keep her on his farm. Price even made Maria sleep in the same room with him and his wife to keep her from running away. It was a dangerous place to be, especially when he started drinking. Maria’s only thought was escape, but she needed help.

Then Charles Bigelow, a wealthy Quaker lawyer, entered the scene. Bigelow worked out of an office near the stage depot in Washington, D.C., raising money to buy slaves and set them free. When he heard of the girl trapped in a bedroom with the notorious Charles Price, her case became his number one project. He rode out to Maryland and offered to buy her on the spot, but Price just laughed at him. Desperate, Bigelow turned to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. Could they please send someone to Washington at once who could help this girl escape, hide her, and escort her to Canada? Bigelow would pay all expenses.

The committee sent a young man whose code name was Powder Boy to case the Price farm. He returned with grim news: The Prices rarely let Maria out of their sight. There was nothing to do but make a plan with her now, be patient, and wait for a break. Surely Price would drop his guard sometime.

The chance came three weeks later, in October of 1855, when Price finally let Maria sleep with the other slaves for one night. Barefooted, Maria took off running shortly after dark, arriving at the prearranged spot where a committee agent was waiting for her. Under cover of darkness, the two hustled off to Bigelow’s office in Washington. Price was furious when he realized Maria was gone. He quickly took out a newspaper advertisement offering a $500 reward for her capture.

A FAVORITE ROUTE

Many of William Still’s Philadelphia passengers went first to Burlington, New Jersey. From there they traveled to Bordentown, New Brunswick, Rahway, and Jersey City. Then they were whisked to the Forty-second Street train station in New York City, where they boarded trains for Syracuse. From there it was on to Niagara Falls and the Canadian border.

THE GIRL WHO ESCAPED IN A Box

In 1855, Lear Green, eighteen, escaped from her Baltimore master in a wooden chest. She was packed away with a quilt, a pillow, a bottle of water, and a little food, then stowed with the other freight aboard a steamship. Her boyfriend’s mother, a free woman, accompanied the chest and twice loosened the ropes to give Lear air. After eighteen hours Lear was deposited on a Philadelphia dock and delivered to a house on Barley Street. She was still alive when the chest was opened. Later she married and went to live in Elmira, New York.

Maria hid in Bigelow’s office while bounty hunters patrolled the nearby coach depot. She took the identity of Joe Wright and did chores around the office in boy’s clothing. Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, the Anti-Slavery Society tried desperately to find a conductor to go to Washington and bring Maria back to William Still’s office so that he could move her on to Canada. The only experienced conductor available was Dr. Howard, a college professor who couldn’t travel until the Thanksgiving holiday, still six weeks away. They continued to wait.

Just after dawn on November 23, 1855, young “Joe Wright,” now dressed in a carriage driver’s cap and long coat, cautiously urged Bigelow’s team toward the White House, where Dr. Howard’s carriage was waiting. As Bigelow greeted Dr. Howard, Maria slipped from his carriage into Dr. Howard’s. The horses snorted nervously as she took the reins and whip. Howard said good-bye and gave the command to drive on, which Maria did, for only the second time in her life. Amazingly, the horses obeyed, prancing straight out through Washington and into the suburbs of Maryland. There Dr. Howard took the reins.

To reach Philadelphia they still had to make it through ninety miles of bounty-hunter-infested countryside. They would need to stop at least twice to feed the horses, and they would have to spend one or two nights at a hotel or farmhouse. When darkness fell, Dr. Howard took a chance. He pulled the horses up to the farmhouse of an old friend and rapped on the door. This man was a slaveholder, to be sure, but Dr. Howard thought it unlikely that he would have heard of Maria. His friend was overjoyed to see him. After hours of conversation, Dr. Howard yawned. He explained that “Joe” had to sleep in the

same room with him, since he sometimes passed out in the night and needed the boy to help him with his medicine. Soon the doctor was in bed, sleeping soundly, and Maria was wrapped up in a comfortable quilt on the floor.

At four o’clock on Thanksgiving Day, Dr. Howard and Maria arrived at William Still’s home in Philadelphia. Dr. Howard dropped her off and disappeared. Still was out, but when he got home, he found a young coachman seated quietly at his table. “Are you the passenger expected from Washington?” Still asked. Without answering, Maria got up and walked outside. Still followed. “Yes,” she whispered, “I am the one the doctor went after, but the doctor told me to tell no one but you and there are others inside.”

Three days later, Maria, still dressed as a boy, was conducted to the home of Louis Tappan in New York City. The Tappan family hid her in their attic, bought her some girl’s clothing, and found a conductor named Reverend Freeman to take her to Canada. Three days later they crossed into safety at Niagara Falls. On the other side, at Chatham, Ontario, they stopped at a boardinghouse, where Reverend Freeman told the proprietor his coachman’s story. Reverend Freeman later wrote: “The proprietor seemed greatly surprised and said, ‘I will call my wife.’ She came, and all the women in the house came with her. They soon disappeared, and ‘Joe’ with them, who, after being gone awhile, returned and was introduced as Miss Maria Weems. The whole company were on their feet, shook hands, laughed, and rejoiced, saying this beat anything they had ever seen before.”

She reunited with other family members who had escaped to freedom in Canada. She went to school at the Buxton Settlement in Canada.