THE CIVIL WAR SOLDIER

The average soldier was about five feet eight inches tall and weighed 1431/2 pounds. His average age was twenty-five, which dropped as the war went on. One soldier in ten died of disease, one in ten was wounded, and one in sixty-five died in battle. Most were farmers or farmers’ sons. A quarter were born in another nation. Nine of ten Confederate soldiers had never owned a slave.

“The recruiting officer didn’t measure my height, but called me five feet, five inches high.”

Wisconsin, 1861

Elisha Stockwell, a farmer’s son from Jackson County, Wisconsin, was fifteen when he first tried to join the Union army. He wrote of his family’s reaction and of his early days as a soldier.

“In September [1861] I was helping a neighbor sack grain and we heard there was going to be a war meeting at our little log school house.” Elisha Stockwell wrote his name down when they called for volunteers, but “my father was there and objected to my going, so they scratched my name out, which humiliated me … My sister called me a little snotty boy, which raised my anger … I could rake, and bind and keep up with the men, so why couldn’t [I] fight like one too?”

Elisha’s next chance came when a friend of his father’s returned home from the war for a few days on leave. Elisha begged to go back with him: “I told him I was bound to go, and if he wouldn’t help me, I would go alone and have to foot it.” The soldier reluctantly agreed. Now Elisha had to figure out how to slip away from his dad. An idea came quickly.

He told his father that there was going to be a dance Sunday night and asked if he could take the oxcart. His unsuspecting father agreed. “I drove up to my brother-in-law’s, tied the oxen to the fence, and went in and saw my sister a few minutes. I told her I had to go down town. She said, ‘Hurry back, for dinner will soon be ready.’ I didn’t get back for two years.”

There was one last hurdle. He had to convince the company captain and the recruiting officer that he was old enough to serve. That turned out to be a cinch. The captain, happy to see any eager recruit, told the recruiting officer that Elisha was clearly old enough. Then the recruiter asked Elisha to state his age. “I [said] I didn’t know just how old I was but thought I was eighteen. He didn’t measure my height, but called me five feet, five inches high. I wasn’t that tall until two years later when I re-enlisted.”

Southern boys were doing the same thing. Just after the shelling of Fort Sumter, sixteen-year-old Mississippian George Gibbs excitedly began stuffing clothes into his sack, planning to go off to a recruiting center. George barely listened as his parents pleaded with him not to go. Finally they gave in, helped him sign up, and went with him to join his company. When the unit lined up to board the train that would take him off to war, George turned to look back at his parents. They were still there, sad-eyed and waving. He stepped out of line, hid from his mates, and burst into tears. “This seemed to help me,” he said, “and I felt better about leaving home.”

A young “powder monkey,” trained to deliver ammunition to gunners in battle, pauses aboard the USS New Hampshire.

Some parents pushed their sons to enlist. Another Mississippian, fifteen-year-old Ned Hunter, was dismissed by a recruiting officer who could see that the boy was obviously too young. Ned’s father stepped forward, put his hands squarely on the table, and glared down at the recruiter. “He can work as steady as any man,” Mr. Hunter said, “and he can shoot as straight as any who has been signed today.” The officer shrugged and handed Ned the pen.

B.C. HARDTACK

One of the hardest things for new soldiers to get used to was army food. The main course was hardtack, or twice-cooked biscuits that looked like crackers, often eaten with small white soup beans. William Bircher, a teenaged diarist from Minnesota, wrote: “Our hardtack was very hard. We could scarcely break it with our teeth … We had fifteen different ways of preparing it. On the march it was eaten raw … A thin slice of nice fat pork was cut down and laid on the cracker, and a spoonful of good brown sugar put on top of the pork. If there was time for frying, we either dropped the dry crackers into the fat and did them brown to a turn … or pounded them into a powder, mixed it with boiled rice and made griddle cakes and honey … minus the honey.” Bircher also figured out how to make hardtack pudding, hardtack stew, and fricasseed hardtack. The letters “B.C.” were stamped on all the unit’s cracker boxes. The boys in Bircher’s unit were sure that meant their hardtack had been first baked “before Christ.”

LOOKING FOR A GOOD FIT

It took months for both armies to produce enough uniforms for the soldiers. Most didn’t fit. Some rebel soldiers started the war wearing Yankee blue, which was scary in battle. One Alabama boy wrote of searching a battlefield for dead Confederate soldiers about his size. “I must confess to feeling very bad doing this,” he wrote, “ … but I had no other course. In just a few weeks my uniform was the equal of anyone’s.”

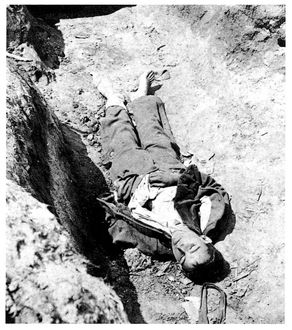

A shoeless fourteen-year-old Confederate soldier lies dead after having taken a bayonet thrust to the heart.

Fresh young recruits were often tested in camp by the older men. Elisha Stockwell encountered a bully right away: “One of [our] company was known as Curley. He was a big husky man and quite handy with his fists. He said he had to try all the recruits to see if they could fight, and proceeded to cuff me around until I got quite enough of that play. I told him I didn’t enlist to fight that way, but if he would get his gun and go outside of the camp, we would stand thirty or forty rods apart, and I thought I could convince him that I could shoot as well as he could. He turned it off as a joke and said he guessed I would pass. I never liked him after that, but he never bothered me again.”

Sometimes it went further. One Confederate boy of fifteen, tired of being teased by an older soldier about how badly his uniform fit, went after his tormentor with a cocked pistol, demanding an apology. The older man grabbed his own rifle and shot the boy dead.

If camp life didn’t toughen boys, the first taste of real battle usually did. Elisha Stockwell’s unit joined the battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862. After spending the first night standing in a soaking rain, they advanced to the front at dawn. As Elisha was walking, he nearly stumbled over a bulky object. He looked down. “[It was] the first dead man we saw … He was leaning back against a big tree as if asleep, but his intestines were all over his legs and several times their natural size. I didn’t look at him the second time as it made me deathly sick.”

Elisha’s unit silently formed a battle line and then flattened themselves against the ground, hearts pounding with fear. On command, they leaped up and sprinted screaming downhill toward rebel soldiers who waited in the bushes. The air quickly filled with smoke and thunder. As he was running, Elisha felt something sharp hit him in the

back of the head. It was a bayonet from one of his own men, who had been shot dead and had fallen forward onto Elisha. He kept running, his vision bouncing up and down, shooting his gun at bushes he could barely see. He felt the hot sting of a ball of lead in his arm, but he kept running and shooting until he heard a call to retreat. The battle had been a disaster: Nearly half of Elisha’s unit was dead or badly wounded. His arm had been injured. And they had lost the camp they were trying to defend.

That night, when he had time to think about his first day of battle, Elisha remembered how he felt when he was waiting on his belly in the grass for the command to charge: “As we lay there … my thoughts went back to my home, and I thought what a foolish boy I was to run away to get into such a mess as I was in. I would have been glad to see my father coming after me.”

When the war ended, he was marching with his unit toward Montgomery, Alabama. They celebrated for a day and then Elisha started walking back to Wisconsin. When he got home, he found that of the thirty-two men and boys from his town who had left with him to fight, only he and two others were still alive. He went back to life as a farmer in Wisconsin.

EMMA SANSOM

Though few put on uniforms, many girls saw action during the Civil War. When her six brothers enlisted in the Confederate army, Emma Sansom took over the family’s Alabama farm with her mother and sister. One spring morning in 1863, sixteen-year-old Emma was working a field when a mounted company of Union soldiers thundered past and raced across the wooden bridge that spanned rain-swollen Black Creek. Once all had crossed, they set the bridge ablaze and waited. When the Confederates pursuing them arrived, the Yankees stood up and opened full fire. Confederate general Nathan Forrest spotted Emma near the gate and sprinted up to ask her if there was anywhere else to cross the creek. She told him of a nearby cattle trail and offered to lead him to the crossing. Under heavy fire, she leaped bareback behind Forrest and guided him and his troops across the stream. Once across, General Forrest’s troops intercepted Yankee forces and kept them from destroying more railroad bridges. The Confederate Congress gave Emma a gold medal for her help, and later a statue of her was erected near the creek. Emma Sansom High School in Gadsden, Alabama, is named in her honor.