“What a wonderful revolution!”

Coastal islands of Georgia and South Carolina, 1862-1865

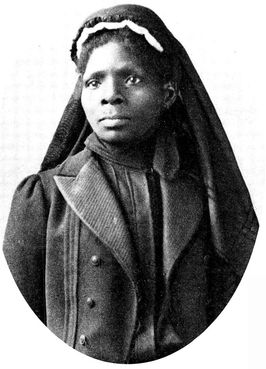

Thousands of African Americans in the South escaped to Union army camps when Yankee soldiers drew near. Carrying all their belongings, they followed the soldiers wherever they went. The Union officers called them “contrabands”—meaning property seized from the enemy. They wondered how to feed them all and where they would sleep. Some Union officers put them to work as laborers, scouts, guides, cooks, laundresses, and teamsters. Hundreds of teachers and nurses came from the North to help them. Along the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, many people who were suddenly both free and homeless turned to a remarkable teenager named Susie King Taylor.

Growing up in Savannah, Georgia, Susie Taylor knew that reading and writing had to be important, as so many people were trying to keep her from doing them. She was a slender, dark-skinned girl, with a kind face and an eagerness to learn. Each morning she and her brother walked out their master’s front door, pretending to be going out to learn a farm trade. Once out of sight, they made a sharp turn and stepped quickly to that most dangerous of places—an ordinary classroom—run by a widowed friend of Susie’s grandmother.

“We went every day about nine o‘clock with our books wrapped in paper to prevent the police or white people from seeing them,” Susie wrote later. “We went in, one at a time, through the gate to the kitchen. She had twenty-five or thirty children whom she taught, assisted by her daughter, Mary Jane. The neighbors would see us going in sometimes, but they supposed we were there learning a trade.” When the teacher ran out of new words to teach Susie, a white friend named Katie O’Connor offered to give her lessons “if I promised not to tell her father.”

In 1862, the year Susie turned fourteen, the Union army captured Fort Pulaski, near Savannah, and took shaky control of the Georgia coast. Slaves poured from plantations and city homes and crowded onto military boats bound for Union camps on islands off the Georgia coast. Susie’s family joined the exodus. On the boat ride over, she fell into conversation with the captain. He asked her if she could read. Proudly, she said yes, and that she could write, too. He gave her a scrap of paper and challenged her to prove it. She wrote down her name and hometown. The officer was astonished. “You seem so different from the other colored people who come from the same place you did,” he finally managed to say. “That’s because I was reared in the city,” she answered.

There was a reason for the captain’s questions. The Union needed someone to teach the illiterate children and adults in the camp on St. Simons Island. Could this newly freed girl handle it? Susie was offered the job and accepted, but refused to begin until they provided her books to work with. When they arrived, she took over a small cabin and started teaching the alphabet to forty children during the day and again to countless adults at night. They were all as hungry to learn as she had once been.

Another important group was stationed on St. Simons Island. Union major general David Hunter, desperately needing soldiers to stave off Confederate attacks on the islands, had given Federal uniforms to a few dozen ex-slaves—although the trousers were red instead of Union blue. He let them fight but didn’t pay them. They were the first black soldiers to fight in the Civil War. One was Edward King, a young sergeant from Darien, Georgia. He and Susie met in camp, fell in love, and were soon married. When his unit was transferred to Port Royal Island, South Carolina, Susie went with him. Though she was officially employed as a laundress, she was far too valuable to spend much time cleaning uniforms. “I taught a great many of my comrades … to read and write when they were off duty,” she wrote. “Nearly all were anxious to learn. My husband taught some also.” And while they were learning, she became the unit’s postmistress, patiently reading letters to the soldiers and helping them write out replies.

THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

“On the first day of January, the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforth, and forever free.”

—President Abraham Lincoln

A SECOND NAME FOR THE FIRST TIME

In the spring of 1862, near Hilton Head, South Carolina, Union commander Ormsby M. Mitchel told former slaves they could now give themselves surnames—last names. This was new. Freed people thought hard about what they wanted their second names to be. Some kept the surnames of their former owners, but most didn’t.

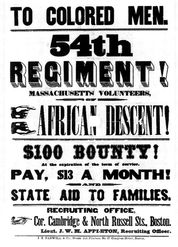

THE FIFTY-FOURTH MASSACHUSETTS

Most Union officers doubted that black soldiers could, or would, fight as well as whites. Major General William Tecumseh Sherman asked: “Is not a negro as good as a white man to stop a bullet? Yes … but can a negro do our skirmishing and picket duty? Can they improvise bridges, sorties, flank movements, etc. like the white man? I say no.”

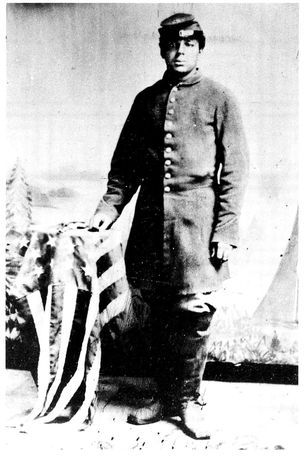

But black boys and men wanted to prove the answer was yes; they felt the war was about them. On January 1, 1863, they got their chance, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that slaves in the rebel states were free and allowing free blacks to join the U.S. Army. Days later, the governor of Massachusetts formed the first unit of free black soldiers, called the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment.

Free African Americans, including many boys, hiked to Boston to enlist. Sixteen-year-old John Henry Johnson walked from Salem, Massachusetts, where he had been taking care of a wounded Union officer. Joseph Christy, sixteen, walked from Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, with his three older brothers. Joseph Henry Green of Boston made up a phony name to fool his parents, and James W. Green of Sherborn, Massachusetts, lied about his age.

After training in the North, the Fifty-fourth attempted to seize control of Fort Wagner, South Carolina, from Confederate forces. To do so, they had to charge up a sandy hill into overwhelming fire. About half the unit was killed, but with them died the notion that black soldiers would wilt in battle. Wrote one New York reporter: “If this Massachusetts 54th had faltered … 200,000 troops for whom it was a pioneer would never have been put into the field. But it did not falter. It made Fort Wagner such a name for the colored race as Bunker Hill has been for ninety years to the white Yankees.”

Susie would have fought, too, if she had had a chance. “I learned to handle a gun very well while in the regiment,” she wrote, “and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading each day. I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun apart, and put it together again.”

Above all, she became a skilled and creative nurse. Once, when a group of wounded men ran out of food, she disappeared for a while and returned with a batch of turtle eggs and several cans of condensed milk. From these she whipped up a custard that not only fed her patients but gave them a break from the monotony of dip toast and dry meat.

Susie was only a mile away on the day the soldiers of the Fifty-fouth Massachusetts—the first unit of black soldiers in the Civil War—led their bayonet assault on Fort Wagner.

Many survivors were horribly wounded by the time they got back to Susie and the other nurses. Many men lost arms and legs. Susie worked around the clock to care for them. When she finally had a moment to think about it, she was amazed by her own calmness. “It is strange,” she wrote, “how we are able to see the most sickening sights, such as men with their limbs blown off and mangled by the deadly shells, without a shudder; and instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain, bind up their wounds, and press cool water to their parched lips, with feelings only of sympathy.”

When the war ended, Susie, then seventeen, went back to Savannah with her husband to begin a new life. Just before their baby was born, Edward King died. Susie opened a school for black children—charging families one dollar a month. Susie later remembered the war years as the best of her life. “What a wonderful revolution!” she wrote. “In 1860 the Southern newspapers were full of advertisements for slaves, but now, despite all hindrances, my people are striving to attain the full standard of all other races born free in the sight of God.”

Private Charles H. Arnum, Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment

FIRST ARKANSAS COLORED REGIMENT’S MARCHING SONG

Oh, we’re the bully soldiers

Of the First Arkansas.

We are fighting for the Union,

We are fighting for the law.

We can hit a Rebel further

Than a white man ever saw.

As we go marching on.

We are done with hoeing cotton,

We are done with hoeing corn;

We are Colored Yankee soldiers now,

As sure as you are born.

When the master hears us shouting

He will think it’s Gabriel’s horn.

As we go marching on.

Of the First Arkansas.

We are fighting for the Union,

We are fighting for the law.

We can hit a Rebel further

Than a white man ever saw.

As we go marching on.

We are done with hoeing cotton,

We are done with hoeing corn;

We are Colored Yankee soldiers now,

As sure as you are born.

When the master hears us shouting

He will think it’s Gabriel’s horn.

As we go marching on.