“It begins to look as if the Yankees can do whatever they please and go wherever they wish—except to heaven.”—Seventeen-year-old Georgian Eliza Frances Andrews

Atlanta Today”

Atlanta, Georgia, 1864

By 1864, the North was winning the Civil War. The Confederate army was running out of supplies and men, while thousands of slaves were strengthening the Union army. Most of the fighting was now taking place in the South. Red-bearded Union major general William Tecumseh Sherman set out to end the war by wiping out the South’s ability to produce food and weapons.

The Union army reached the outskirts of Atlanta, the South’s biggest city, in mid-July. Sherman was amazed by how Atlantans had prepared. “The whole [city] is a fort,” he wrote. And he was right. Residents had stripped the wood from the walls of their houses and hammered together fences around the city. Behind the walls were trenches filled with exhausted but determined Confederate soldiers. And behind them were ordinary Atlantans waiting for the worst and hoping for the best. Instead of trying to storm the city, Sherman decided to bombard it from a distance with cannon fire and starve the Confederate soldiers by cutting off roads and railroads that delivered their food. Deep in Atlanta was a ten-year-old girl named Carrie Berry.

Until that spring she had lived a happy, ordered life in a big house with her parents, her sister Zuie, and a black servant girl named Mary. Aunts and uncles lived all around her. But when the shelling began, the Berrys frantically dug a hole deep in the ground and covered it with wood and tin. They scrambled to their “cellar” whenever they heard the blast of Union cannons outside the walls. Carrie kept a diary throughout the siege of Atlanta.

July 19. “We can hear the cannons and muskets very plain, but the shells we dread. One has busted under the dining room … One passed through the smokehouse and a piece hit the top of the house and fell through but we were at Auntie Markhams’s, so none of us were hurt. We stay very close in the cellar when they are shelling.”

August 3. “This was my birthday. I was ten years old, but I did not have a cake. Times were too hard so I celebrated with ironing. I hope by my next birthday we can have peace in our land so that I can have a nice dinner.”

August 5. “I knit all the morning. In the evening we had to run to Auntie’s and get in the cellar. We did not feel safe in our cellar, they fell so thick and fast.”

August 15. “Soon after breakfast Zuie and I were standing on the platform between the house and the dining room. [A shell] made a very large hole in the garden and threw the dirt all over the yard. I never was so frightened in my life. Zuie was as pale as a corpse … It did not take us long to fly to the cellar. We stayed out till night.”

August 21. “Papa says that we will have to move downtown somewhere. Our cellar is not safe.”

August 23. “There is a fire in town nearly every day. I get so tired of being housed up all the time. The shells get worse and worse every day. O that something would stop them.”

A few days later Carrie got her wish. On August 31, Sherman’s army won a decisive battle and the next day Confederate forces abandoned Atlanta. Carrie heard rumors that the oncoming Yankees were going to burn all the houses in the city, and all the residents would have to evacuate. Union troops began to pour into Atlanta. (Carrie called them Federals in her diary.)

September 2. “We all woke up this morning without sleeping much last night. The Confederates had four engines and a long train of boxcars filled with ammunition and set it on fire last night which caused a great explosion which kept us all awake. Everyone has been trying to [gather up] all they could before the Federals come in the morning. They have been running with sacks of meal, salt and tobacco. They did act ridiculous breaking open stores and robbing them. About twelve o’clock there were a few Federals came in. [We] were all frightened. We were afraid they were going to treat us badly. It was not long before the infantry came in. They were orderly and behaved very well.”

ADVANTAGES

The South had bold and brilliant officers, but the North had advantages in materials. The factories of Massachusetts alone produced more manufactured goods than all the Confederate states combined. Northerners had another advantage, too: education. Slaves were not allowed to read, and only one of every three Southern white children was enrolled in school, compared to three of four in the North.

FORAGING FOR FOOD

Union soldiers were encouraged to forage for food from the surrounding farms. William Bircher, a drummer boy from a Minnesota regiment, went on a foraging trip one day while others in his regiment were tearing up railroad tracks. “I came to a very fine plantation;’ he wrote,”where the white folks had all run off, leaving nobody at home but an old Negro couple. I was the first Union soldier they had seen. After I told them they were now free and could go where they wished, and that I was one of ‘Massa Lincum’s’ soldiers, their joy knew no bounds … I told them I wanted something to eat. The [man] dug up about a peck of yams and the old lady went to the barn and got me about two dozen eggs. She also gave me a piece of bacon.” Best of all, Bircher led two fat cows back to his unit.

A CIVIL WAR MATH PROBLEM

“If one Confederate soldier kills ninety Yankees, how many Yankee soldiers can ten Confederate soldiers kill?”

—From a math book for Southern grade-school children during the Civil War

September 4. “Another long and lonesome Sunday … We have been looking at the [Yankee] soldiers all day. They have come in by the thousands. They were playing bands and they seem to be rejoiced. It has not seemed like Sunday.”

But on September 8, their worst fears were confirmed: Sherman had indeed decided to burn Atlanta. Confederate officers ordered all residents to leave the city. One by one Carrie’s friends and relatives departed, but her father, a wealthy businessman, made up his mind to stay even if it meant cooperating with the Yankees. While the rest of the family was packing, Maxwell Rufus Berry went downtown and offered to work for the Union army if it would guarantee his family’s safety in Atlanta. He came back home cheerfully announcing they could stay. Early in November, Union soldiers began to enter homes and businesses, first taking anything of value, and then setting piles of furniture ablaze. When flames found the gunpowder that many Atlantans had stored in their homes, explosions rocked the city. Balls of fire arced through the sky, and flying cinders filled the air. One Union soldier called it “the grandest destruction I have ever seen.” Carrie was terrified.

November 8. “We lost our last hog this morning early. Soldiers took him out of the pen. Me and Buddie went around to hunt for him and everywhere that we inquired they would say that they saw two soldiers driving off to kill him. We will have to live on bread.”

November 12. “I could not go to sleep for fear that they would set our house on fire.”

November 14. “They came burning Atlanta today. We all dread it because they say that they will burn the last house before they stop.”

November 15. “This has been a dreadful day. Things have been burning all around us. We dread tonight because we do not know what moment they will set our house on fire.”

November 16. “Oh, what a night we had. They came burning down the storehouse and about night it looked like the whole town was on fire. We all set up all night. If we had not [stayed up all night] our house would have been burnt up for the fire was very near and the soldiers were going around setting houses on fire where they were not watched. They behaved very badly. They all left town about one o’clock this evening and we were glad when they left for nobody knows what we have suffered since they came in.”

With Atlanta in ashes, most of the Union soldiers marched off toward Savannah. Carrie’s family had been one of about fifty families to remain in Atlanta. Her house had been spared, but now it stood as an island in a sea of cinders.

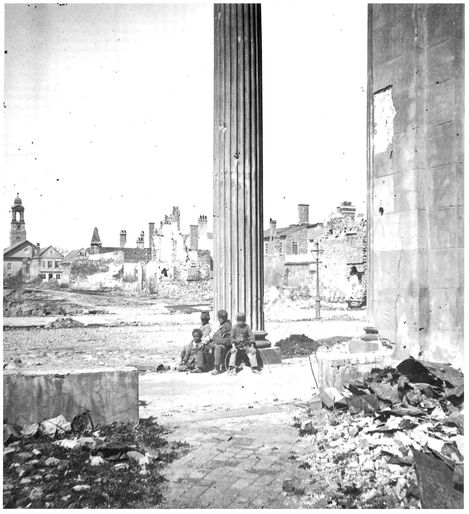

Other cities besides Atlanta were devastated by Union troops. These boys rest in the ruins of Charleston, South Carolina.

After the Union soldiers left, her father was arrested for staying in Atlanta with the Yankees, but was soon released. In the new year of 1865, Carrie’s mind returned to school, church, and a new sister. She remained in Atlanta throughout her life, married an ex–Confederate soldier, and became the mother of two sons and a daughter.

THE BURNT COUNTRY

After burning Atlanta, General Sherman sent Union soldiers marching eastward in two parallel columns forty miles apart and told them to destroy everything in their path. They did, including major cities, until they reached the Atlantic Ocean. “War is hell,” Sherman reminded his troops. Seventeen-year-old Eliza Frances Andrews passed over a stretch of central Georgia just after Sherman’s army had left. Here is how she described it in her diary: “There was hardly a fence left standing all the way from Sparta to Gordon. The fields were trampled down and the road was lined with carcasses of horses, hogs and cattle that the invaders, unable either to consume or to carry away with them, had wantonly shot down to starve out the people and prevent them from making their crops. The stench in some places was unbearable; every few hundred yards we had to hold our noses or stop them with cologne.”