“When the Pony Express dashed past, it seemed almost like the wind racing over the prairie.”––Mary Ann Stucki, a Mormon girl who saw the riders during her journey to Salt Lake in 1860

California to the Mississippi River, 1860

If you wanted to deliver a business letter or newspaper across the West in 1860, the fastest way was to send it by Pony Express. That’s how people in Salt Lake City learned that Abraham Lincoln had been elected president, and that’s how San Franciscans found out that the Civil War had begun.

The Pony Express was a two-thousand-mile-long relay race against time. Investors spaced 190 stations about ten miles apart between Sacramento, California, and the Mississippi River. Each station had two or three fast horses ready to go. Every morning a rider took off from Sacramento with a leather pouch full of letters written on the thinnest paper available and galloped east as fast as he could to the first station, Folsom.

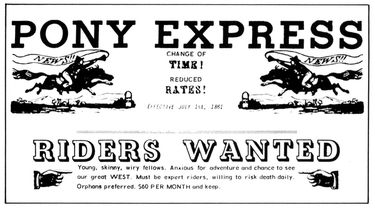

Though some historians doubt the authenticity of this advertisement, there is little doubt that the company was after young, light daredevil riders.

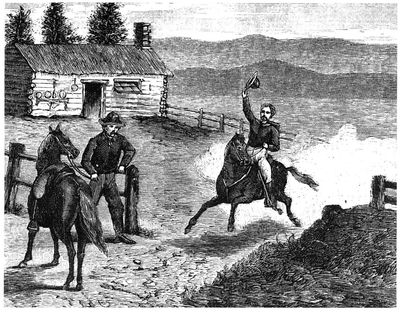

A Pony Express rider gets set to leap from one horse onto another.

There he leaped off the horse, gulped down water, grabbed his mail pouch, jumped onto a fresh mount, and thundered off. The switch took two minutes. The same thing happened with a westbound rider starting from St. Joseph, Missouri. Riders rode about eight switches before they rested. They took pride in never slowing down for anything—storms, Indians, thieves, or even fatigue.

They were lightning fast. News of Lincoln’s election traveled from St. Joseph to Denver—a distance of 665 miles—in two days and twenty-one hours. The text of Lincoln’s inaugural address traveled two thousand miles in seven days and seventeen hours. Many of the riders were teenagers, because they were light and adventuresome. Young J. H. Keetley rode the first eastern leg, starting each morning from St. Joseph, Missouri. People got up early and lined the streets just to catch a glimpse of him as he tore out of town. Keetley later wrote, “[We] bounded out of the office door and down the hill at full speed … It was then that all St. Joe, great and small, were on the sidewalks to see the pony go by … We always rode out of town with silver mounted trappings decorating both [rider] and horse and regular uniforms with plated horn, pistol, scabbard and belt and gay flower-worked leggings and plated jingling spurs resembling, for all the world, a fantastic circus rider.”

The most famous rider of all was William F. Cody, later known as Buffalo Bill. He was a boy who grew up in the saddle. After his father died, eleven-year-old Bill found a job delivering messages by mule for a Kansas freight company. He was fourteen when he heard that the Pony Express had started up. He thought the job had been invented for him. At first the hiring agent at his local station said he was too young, but finally gave in and let Bill take a test run. Bill won his job by blistering the course between Red Buttes and Three Crossings in nearly record time.

He quit after two months but then missed the excitement and tried to get a job at a station farther west. According to Bill, this is how his job interview went: “My boy, you are too

YOUNG, LIGHT DAREDEVILS

It cost five dollars, paid in advance, to send a letter on the Pony Express. The goal was to advance the mail 250 miles per day. Only business letters were allowed. Riders were hired for strength, stamina, and lightness. Their average age was eighteen. They made about $120 a month, a good wage then, and got bonuses for especially quick rides. The riders who brought news of one Civil War battle to Sacramento a day before schedule divided a bonus of $300.

young for a Pony Express rider,” the hiring agent said. “I rode two months last year on Bill Trotter’s division,” Bill replied coolly.”I filled the bill then and I think I’m even better now.” The agent’s eyes widened in recognition. “What! Are you the boy that was riding there, and was called the youngest rider on the road? … I’ve heard of you.”

And so Bill Cody was off again, wringing adventure from every mile. Once, when the rider expected at Three Crossings station didn’t show up (he had been shot dead in a saloon the night before), Bill grabbed the man’s mail sack and took off in his place. He rode 322 miles by himself from station to station without mishap and arrived on time, even though he spent part of his ride bent flat back in the saddle dodging robbers’ bullets. According to Bill Cody (who was known to stretch a story), that was the day he set the all-time Pony Express endurance record.

The Pony Express lasted only eighteen fabulous months. It lost a race to electricity, which could push messages along a telegraph wire even faster than Bill Cody could urge a half-breed California mustang along a dusty trail.

He served as a Union scout in the Civil War, then became, among other things, a wrangler, hotel owner, gold-panner, rancher, and meat hunter for the Union Pacific Railroad. In one year alone, he boasted of killing 4,280 buffalo. In 1883, he started Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which toured America, and in which he, of course, starred. He died in 1917.

Eighteen-year-old Richard “Ras” Egan rode a seventy-five-mile route between Salt Lake City and Rush Valley.