GOLD MOUNTAIN MALES

Nearly twelve thousand Chinese went to Gold Mountain in 1852. Only seven were women or girls. Fifty years later only 5 percent of all Chinese in the United States were females. According to Chinese custom and religion, women were expected to stay within the walls of their villages and tend to their families. Also, it was very expensive for two to go, and families thought that if a wife stayed at home, the husband would be more likely to return to China. Many of the Chinese teenagers and men who left were married, and their wives knew they might never see them again. One song warned:

If you have a daughter, don’t marry her to a Gold Mountain man …

The spider will spin webs on top of the bedposts,

While dust fully covers one side of the bed.

“If you will, you can.”––Ng Poon Chew’s grandmother’s parting words to him when he left China for the United States

Pearl River Delta, China, and San Francisco, California, 1850s–1880s

In 1848, nuggets of gold were discovered in several California rivers, triggering a worldwide gold rush. A few Chinese merchants living in California got lucky, and in the winter of 1850–1851, they journeyed back to their villages carrying fortunes of between $3,000 and $4,000 each. Overnight, thousands of young Chinese men and teenage boys borrowed the money for the trip and crowded aboard small ships bound for Gam Saan, or “Gold Mountain,” as California was called. Many who set out to be miners ended up with very different jobs. Ng Poon Chew and Lee Chew were two of China’s Gold Mountain boys.

One day thirteen-year-old Ng Poon Chew looked up to see his long-lost uncle coming up the road from the Tam River. Overjoyed, Ng followed him inside the family house and watched him reach into the folds of his blue traveling blouse and pull out eight heavy sacks. He dropped them one by one on the table and smiled. Each was filled with 100 Mexican silver dollars. From that moment on, Ng could think of nothing but reaching Gam Saan.

Such scenes were taking place throughout Kwangtung Province, on the coast of south China. Nearby, sixteen-year-old Lee Chew quickly lost all interest in farming when he saw all the things a neighbor who had returned from Gold Mountain could buy: “He took ground as large as four city blocks and made a paradise of it. He put a large stone wall around and let some streams through and built a palace and a summer house … The man had gone away from our village a poor boy. Now he returned with unlimited wealth. It filled my mind with the idea that I, too, would like to go to the country of the wizards and gain some of their wealth.”

Parents couldn’t hold the boys. Some parents mortgaged a field or sold a pig to secure a loan from a ticket seller in Hong Kong. Their children promised to send money soon to pay off the loan and then bid tearful good-byes. Ng Poon Chew set off with his cousin in 1880. Each boy attached a bedroll containing a package of herbal medicines to a bamboo

pole, hoisted the pole across his shoulders, then headed for the river. They had their heads shaved, except for a single long braid in back, and wore loose blue jackets and broad, umbrella-shaped hats that shaded them from the sun. They boarded a slow-moving boat called a junk, which pulled them down the Tam River into the mouth of the Pearl River and across the bay to Hong Kong.

Chinese boys and men bound for Gold Mountain aboard the steamship America

Lee Chew sailed with five friends. He had a hundred dollars from his father tucked into his blouse. His grandfather had told him that Americans were “wizards” and “barbarians,” and he was worried that maybe his grandfather was right. Things were different from the

start. He couldn’t sleep on the ship: “All my life I had been used to sleeping on a board bed with a wooden pillow, and I found the steamer’s bunk very uncomfortable because it was too soft. I was afraid of the stews [we ate], for the thought of what they might be made of by the wicked wizards of the ship made me ill. Of the great powers of these people I saw many signs. The engines that moved the ship were wonderful monsters, strong enough to lift mountains.”

DIFFERENT DIETS

The habits of Chinese railroad workers were very different from those of the whites who worked with them. At the end of a workday, exhausted men from both groups put their tools down and went to dinner. But first, each Chinese worker filled his tub with hot water from a giant boiler the cook had ready. He sponged himself and changed clothes. Then he sat down to his evening rice. It was flavored with oysters, abalone, cuttlefish, mushrooms, and bamboo shoots brought from China. Chinese workers drank hot tea several times a day. Whites ate beef, beans, bread, butter, and potatoes, and they drank water that was not boiled free of impurities. Some thought that the Chinese workers were able to work longer because they had a healthier diet.

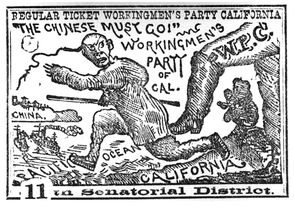

Candidates for California’s Workingmen’s Party campaigned on anti-Chinese sentiment.

Two months later, they arrived in San Francisco. They went through customs, were examined for diseases and frisked for opium, and then tromped down the ship’s ramp into the clamor of San Francisco’s waterfront. At first Chinese immigrants were welcomed to America, but as more and more arrived, attitudes had hardened. Many whites feared that the Chinese, who were tough and disciplined workers, would take away their jobs. Furthermore, most Chinese kept to themselves, cooked their own food, worshiped in their own way, and usually did not speak English.

Some whites wouldn’t tolerate these differences. Gangs of boys and young men often waited for the half-starved Chinese newcomers at the bottom of the ramp and greeted them with a shower of stones, potatoes, and mud. The Chinese made their way to agents of “Six Companies” —groups of Chinese businessmen—who separated them by their home villages and hustled them off to the city’s Chinese quarter. Sometimes the gangs ran alongside, screaming curses and pulling them out of the wagons by their braids. “Often,” wrote one who watched such scenes, “they reach [Chinatown] covered with wounds and bruises and blood.” Most recovered quickly. “A few days living in the Chinese quarter,” wrote Lee Chew, “made me happy again.”

Many Chinese boys got their first jobs as houseboys in the homes of whites. Ng was hired by a rancher who couldn’t pronounce his name. For two dollars a week he worked from dawn till nightfall gardening, cleaning, watching children, cooking, and serving meals. The worst times were when he had to go to the store and was beaten by gangs and forced to surrender the groceries. Lee Chew earned $3.50 per week working for a family of four. “I didn’t know how to do anything, and I did not understand what the lady said to me, but she would take my hands and show me how to cook, wash, iron, sweep, dust, make beds, wash dishes, clean windows, paint and brass, polish the knives and forks.”

In the 1860s, thousands of teenage boys and young men went from China to California to build the western portion of the first

transcontinental railroad. Two companies were racing to see which could build the most miles of track. Workers for the Union Pacific Company began in Omaha, Nebraska, and headed west. Workers for the Central Pacific began in Sacramento and moved east. The Union Pacific crew, consisting mostly of Irish immigrants, got off to a great start, racing over the flat prairies. But in 1865, after two years of trying, the Central Pacific had managed fewer than fifty miles of track. Few workers in California seemed interested in the backbreaking labor of blasting a railroad bed through the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains.

Frustrated, the Central Pacific hired fifty Chinese workers in 1865. This was embarrassing because one of the company’s main investors, Leland Stanford, had been elected governor of California partly by vowing to prevent more Chinese from entering the United States. At first whites refused to work with the Chinese. But the Chinese proved well organized, hardworking, and quick to learn. After hearing one complaint too many, Charles Crocker, superintendent of the Central Pacific, faced down a group of whites. “If you can’t get along with [the Chinese],” he said, “we’ll let you go and hire nobody but them.”

As teams chipped and blasted through the Sierra Nevada, the railroad company sent ships to China to get more workers. Groups of uneducated young Chinese farmers of the Sinning and Sinhwui districts clustered around marketplace notices advertising jobs for a long-term project in the Gold Mountain. Seven thousand Chinese workers sailed off to San Francisco in little more than a year.

They were taken to the mountains, organized into camps, and put to work for one dollar a day. Their mightiest challenge came when the tracks reached Cape Horn Pass. There, a sheer cliff rose fourteen hundred feet straight up from the deep green American River. The job, somehow, was to blast a flat ledge out of the cliff face near the top. It had to be wide enough to make a bed for railroad tracks. Some accounts say that the problem was solved when a Chinese interpreter told a crew boss how they had built roads along steep cliff faces in the Yangtze valley. Days later, loads of reeds were brought up from San Francisco, and by campfire the Chinese stayed up weaving waist-high wicker baskets and attaching them to ropes. Symbols were printed on the baskets to repel evil spirits.

Young Chinese workers prepare to move by handcart to another section of the Central Pacific Railroad.

THE EXCLUSION ACT

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Motivated by racial prejudice, the law stopped Chinese people from emigrating to the United States. The law read, “Whereas, in the Opinion of the Government of the United States the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory … no State court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship.” The law remained in effect until 1943.

The next day teams of three climbed to the top of the cliff, carrying the baskets. Ropes were attached to each corner of the basket and then lashed to a central cable. Then one Chinese worker got in. Only the bravest, smallest, and lightest—and probably often the youngest—were chosen to be “basket men.” Once seated, they were lowered over the cliff ledge on long ropes. Trying not to look down, they swayed in the wind like spiders on long strands along the cliff faces, sometimes bumping into one another. When they reached the level of the railroad bed to be blasted, they grabbed a twig or branch to steady the basket, chipped a hole into the cliff with a small ax, inserted gunpowder into the hole, and lit a fuse. When the fuse caught, the worker in the basket waved frantically for his partners above to pull him up, crying out for them to hurry. Some didn’t wait and shinnied up the ropes before the rock exploded in a shower of stone. Some didn’t make it. All summer and fall the boys and men worked the face of the cliff. It took three hundred basket men and boys ten days to blast a single mile of railroad bed at Cape Horn Pass.

When the transcontinental railroad was finished in 1869, most Chinese workers were left on their own without a job or future. Though some twelve hundred Chinese workers had died, they received little recognition for having conquered the Sierra and done the hardest work of the project. Some tried to find work with other railroad companies, while others returned to San Francisco. Railroad work had not prepared them to be houseboys like Ng Poon Chew or Lee Chew, so they looked for work in factories. Some decided it was enough to have wrestled both the Sierra Nevada and Gold Mountain. They tucked their savings into their traveling blouses and went home.

Ng Poon Chew survived many hard times, including the deliberate burning of his school, before becoming the first Chinese Presbyterian minister on the Pacific Coast. Lee Chew saved his houseboy’s wages and opened a laundry business for railroad workers. Then he moved to New York City, where he bought his own laundry shop in Chinatown.