“I never had a boyhood.”

Texas to Nebraska, 1871—1878

Between the end of the Civil War and the 1890s, cowpunchers pushed millions of balky cows, bulls, longhorn steers, and horses from Texas north to the new railroads. There the animals were jammed into boxcars and sent to slaughterhouses to feed the masses in eastern cities. Many cowboys were former Confederate soldiers still hungry for action. Their lives were so hard that two out of three never went on the trail again after their first time. But boys throughout the country yearned to become cowboys, and some had their dreams come true. One was Teddy Abbott, a frail ten-year-old boy born in England and brought to Nebraska in 1871 by his parents. Soon after arriving, his dad went to Texas and bought a herd of cattle.

Teddy got to go with the cowpunchers who drove them north to his father’s ranch.

“I was the poorest, sickliest kid you ever saw, all eyes, no flesh on me whatever,” Teddy Abbott wrote. “If I hadn’t have been a cowpuncher I never would have growed up. The doctor told my mother to ‘keep him in the open air.’ She kept me there, all right, or fate did. All my life.”

Even at the age of ten, Teddy had troubles with his father. Mr. Abbott was a distant man, absorbed in his already mounting business losses. As they drove the cattle north along the broken, treeless trail, he had little to say to Teddy except to give him orders and bawl him out for one mistake or another. When they came to the first dangerous crossing, at the Red River, Mr. Abbott decided it was time to make a “man” out of Teddy.

“[My father] said he was to tie me to my horse to cross the Red River, so if the horse drowned I’d be sure to drown too. I kicked like a steer, as I could swim, and the rest of the men talked him out of it.”

When they got back to Nebraska, Teddy’s father ordered him to take care of the cattle. Since Mr. Abbott knew little about livestock, Teddy had to learn on his own. That was fine with him.

“In the summer [the cattle] were turned out on the range and I was out there with them, living in camp ten miles from home and cooking my own grub like a man. That was how I got to be so friendly with Texas cowpunchers and tried to be just like them … One of the Texas fellows gave me my first six-shooter when I was about thirteen. The cylinder was burnt out, and he said, ‘Promise me you’ll never load it’ … but one day I had it home, and my older brother Frank got hold of it, and he loaded it though I told him not to. It pretty near blew his hand off … My father found out and took it outside and smashed it with an ax. As soon as I could I got another one.”

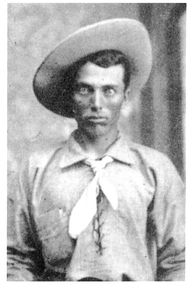

One afternoon in 1876, sixteen-year-old Teddy Abbott (above) staggered drunk out of a saloon and paid a photographer to take his picture. His mother hated it. Three years later he bought new clothes, slicked down his hair, and tried to make up with a new photo (below).

THE GREAT BUFFALO SLAUGHTER

As the range filled up with white settlers and their cattle, buffalo nearly disappeared. When Lewis and Clark explored the West, from 1804 to 1806, there were about sixty million buffalo. The animals gave Plains Indians food, shelter, clothing, beds, blankets, fuel, strings for bows, glue, thread, saddle coverings, even boats. But just fifty years later two-thirds of the buffalo were gone. After the railroads came, the land stank of rotting buffalo meat. Passengers shot them from train windows. President Teddy Roosevelt once spoke of a friend who rode all the way across Montana and “was never out of sight of a dead buffalo, and never in sight of a live one.” By 1883, only a few buffalo survived in parks. Below are an estimated 40,000 hides purchased for a Dodge city firm in 1874.

Though he was young, Teddy developed a reputation for understanding the Nebraska range and being good with cattle. Each summer the cowpunchers came up from Texas, driving cattle to the B&M railroad in Lincoln. Teddy started a business, charging local ranchers $1.50 per animal to take care of their cattle and helping the Texans get their cattle to the trains. These long drives made him even tougher:

“There never was enough sleep. Our day wouldn’t end until about nine o‘clock, when we grazed the herd onto the bed ground. After that [we] had to stand two hours of night guard … Sometimes we would rub tobacco juice in our eyes to keep awake. It was like rubbing them with fire … The cook yelled ‘roll out’ at half past three. I would get maybe five hours’ sleep when the weather was nice. If it wasn’t so nice you’d be lucky to sleep an hour. But the wagon rolled on in the morning just the same.”

When Teddy was fifteen, three Texans hired him to help deliver a herd of five hundred cows to a Nebraska rancher. On that job he got his first look at every cowpuncher’s nightmare—a stampede:

“That night it come up an awful storm. It took all four of us to hold the cattle and we didn’t hold them, and when morning come there was one man missing. We went back to look for him, and we found him among the prairie dog holes, beside his horse. The horse’s ribs was scraped bare of hide, and all the rest of horse and man was mashed into the ground as flat as a pancake. The only thing you could recognize was the handle of his six-shooter … I’m afraid his horse stepped into one of them holes and they both went down before the stampede … After that, orders were given to sing when you were running with a stampede so the others would know where you were.”

Teddy began to spend his nights in the saloons of Lincoln, Nebraska. His pockets were stuffed with the silver dollars he had earned with his own hard work. He tried to impress men at the bars by buying them round after round of whiskey, and they felt no guilt about soaking up a boy’s pay. One day when he was sixteen, Teddy staggered out of a saloon and hired a photographer to take his picture. It shows a boy with a sagging face, half-closed eyes, and a cigar jammed in his mouth.

On the trail

SINGING COWBOYS

“One reason I believe there was so (Omany songs about cowboys was the custom we had of singing to the cattle on night herd. The singing was supposed to soothe them and it did … if you wasn’t singing, any little sound in the night—it might just be a horse shaking himself—could make them leave the country; but if you were singing they wouldn’t notice it.”

—Teddy Abbott

A preacher went to warn Mr. Abbott that Teddy was on the wrong path. “My old man went up in the air … But what could he expect? He’d kept me out there with the cattle, living with all those men, and all they’d talk about was bucking horses and shooting scrapes and women. I never had but three winters at school, and they was only parts of winters. I was a man from the time I was twelve years old—doing a man’s work, living with men, having men’s ideas.”

At the end of his seventeenth summer, Teddy came home from his camp on the range, his pockets jingling with silver dollars. He was very proud of himself. His father didn’t even look up. He told Teddy, “You can take old Morgan and Kit and Charlie and plow the west ridge tomorrow.” That was it. Instead, Teddy took off. He stopped in town and bought a bed, a tent, three horses, and a gun. Then he rode all the way to Austin, Texas, and hired on with a trail outfit to help drive seven thousand wild horses back north.

It took nearly a year to get back to Nebraska. After a lot of thought, Teddy decided to visit his family. He wanted to show his mother that he had amounted to something. First he stopped in town and bought some new clothes and had another picture taken for her, to wipe away the memory of the old one. He loved the way it turned out. “I had a new white Stetson hat that I paid ten dollars for and new pants that cost twelve dollars, and a good shirt and fancy boots. They had colored tops, red, white and blue, with a half-moon and star on them. Lord, I was proud of those clothes! They were the kind of clothes top hands wore, and I thought I was dressed right for the first time in my life.”

But the visit went sour from the start: “When I got there and my sister saw me she said, ‘Take your pants out of your boots and put your coat on. You look like an outlaw.’” It didn’t take Teddy long to head back for the trail.

He became a well-known Montana rancher, songwriter, and western storyteller. When Teddy was an old man, a writer described him like this: “Today he is seventy-eight years old, tough as whipcord, diamond-clear as to memory and boiling with energy. He can ride me into the ground any day.”