“I tried praying to Jesus for candy and oranges.”

Arizona, 1899

By 1877, there were forty whites for every Indian in the West. Up until 1890, whites and Indians strugged to control the same land, with Indians steadily losing ground. In battle after battle, U.S. army units, filled with Civil War veterans, gunned down Indian men, women, and children. Indians were herded onto government-controlled “agencies” and then given reservations on the poorest land.

Scholars and government officials debated what to do about the “Indian problem.” Some, like Civil War hero William Tecumseh Sherman, thought it best that they be put to death. A group of white church leaders and government officials who called themselves Friends of the Indian had a different idea. Starting in 1883, they set up nearly two hundred Indian schools around the nation. Children as young as five were taken from their families and sent off to learn the ways of whites. One was a stout, curious Hopi Indian boy whose people lived in the high desert near the Grand Canyon. His name was Chuka, which means “Mud.” As an adult, he wrote about what going to an Indian school had been like.

“I grew up believing that whites are wicked, deceitful people. It seemed that most of them were soldiers, government agents or missionaries, and that quite a few were Two-Hearts. The old people said that the whites were tough, possessed dangerous weapons, and were better protected than we were from evil spirits and poison arrows.”

When Chuka was small, a school run by white missionaries was opened at the foot of a mesa in New Oraibi, where he lived. One September morning he watched as his older sister became the first in his family to go down the hill to the school. He was shocked when she returned:

“The teacher cut her hair, burned all her clothes, and gave her a new outfit and a new name, Nellie. She stopped going after a few weeks, and tried to keep out of sight of the whites who might force her to return. About a year later she was captured by the school principal [who] compelled her to return to school. The teacher had forgotten her old name and called her Gladys. Although my brother was two years older than I, he managed to keep out of school until about a year after I started, but he had to be careful not to be seen by whites. When finally he did enter the day school at New Oraibi, they cut his hair, burned his clothes and named him Ira.”

FRIENDLIES AND HOSTILES

Chuka’s people prayed to gods of the sun, the distant oceans, the moon and stars, the eagle and hawk, and gods of the wind, lightning, thunder, rain, and serpents. He ate kiki bread and dumplings made of blue cornmeal. He washed his hair in yucca suds and purified his clothes in the smoke of juniper and piñon sap. His village was split about the missionary teachers. Those who cooperated with whites were called Friendlies. Those who didn’t were Hostiles. Chuka’s family was split, too. They were officially Friendlies, but the elders he trusted taught Chuka to view whites with suspicion.

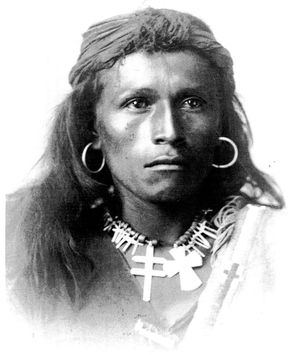

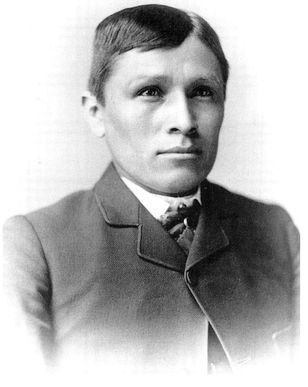

A Navajo boy just before enrolling in an Indian boarding school

When Chuka was nine, it was his turn. He made up his mind to go to school on his own terms: “I did not want a policeman to come for me and I did not want my shirt taken from my back and burned. So one morning in September I left it off, wrapped myself in my Navajo blanket, the one my grandfather had given me, and went down the mesa barefoot and bareheaded.

“I reached the school late and entered a room where boys had bathed in tubs of dirty water. Laying aside my blanket, I stepped into a tub and began scrubbing myself. Suddenly a white woman entered the room, threw up her hands and exclaimed, ‘On my life!’ I jumped out of the tub, grabbed my blanket and started back up the mesa at full speed … Boys were sent to catch me and take me back. They told me that the woman was not angry and that ‘On my life!’ meant that she was surprised. They returned with me to the building, where the same woman met me with kind words that I could not understand … She cut my hair, measured me for a good fitting suit, called me Max, and told me through an interpreter to leave my blanket and go out to play with the other boys.”

HOPI GAMES

Most of Chuka’s time was spent in play until he went to school. “We shot arrows at targets, played old Hopi checkers, and pushed featheredged sticks into corncobs and threw them at rolling hoops of cornhusks. We wrestled, ran races, played tag, kickball, stick throwing and shinny. We spun tops with whips and made string figures on our fingers. Another game I liked was making Hopi firecrackers. I mixed burro and horse dung, burned a lump of it into a red glow, placed the coal on a flat rock, and hit it with a cow horn dipped in urine. It went ‘bang’ like a gun.”

The lessons Chuka learned in school seemed strange: “The first thing I learned in school was ‘nail,’ a hard word to remember. Every day when we entered the classroom a nail lay on the desk. The teacher would take it up and say, ‘What is this?’ Finally I answered ‘nail’ ahead of the other boys and was called ‘bright’ … I learned little at school the first year except ‘bright boy,’ ‘smart boy,’ ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ ‘nail,’ and ‘candy.’”

When Chuka was eleven, he switched to a boarding school a two days’ burro ride away from home. His mother and father rode to school with him and dropped him off. When they mounted up to return home, his father gave him some parting advice: Don’t run away, he said, because “we would not know where to find you and the coyotes might eat you.” And then they were gone. A teacher cut his summer hair again and gave him new clothes. When he did not answer to the name Max, they called him Don. He gave up and tried to think of himself as Don. His confidence faded. He had been a big, tough boy at home, but now he lost fights. The food tasted terrible—hash, prunes, and tea. The matron told him to pray to Jesus each night, so he cupped his hands and prayed for oranges and candy but none came down from the sky. Sometimes in the evenings he and a friend climbed a high hill and looked out over the land. On the clearest days he could faintly see his mesa. Especially at these times, he longed with all his heart to go home.

The same Navajo boy, now called Thomas Torlino, a short time after enrolling at the Indian school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1886

FIRST TRAIN

“As I was watering the ponies, a … noise pealed forth from just beyond the hills. The ponies threw back their heads and listened; then they ran snorting over the prairie. I leaped on the back of one of the ponies and dashed off at full speed. It was a clear day; I could not imagine what had made such an unearthly noise. It seemed as if the world were about to burst in two. I got upon a hill as a train appeared. ‘O!’ I said to myself, ‘that is the fire-boat-walks-on-mountain I have heard about!’”

—Oyihesa, a Sioux boy remembering the first time he ever saw a train

A BOY WHO GREW OLD TOO EARLY

Crow Foot was born in 1876, on the eve of the last major Indian victory over whites, the battle of the Little Big Horn. He was the son of Sitting Bull, the greatest of Sioux chiefs. Crow Foot spent his youth fleeing with his family from U.S. soldiers who wanted to capture his father for his role at Little Big Horn. He deeply admired his father.

“Crow Foot was not like the rest of the boys,” wrote one who met him. “He grew old too early. He did not get out and mingle with the boys and play their games. He was more with the old men … [They were] training him for the chieftainship.” When food ran low, Sitting Bull reluctantly surrendered. But instead of giving his rifle to army troops, he handed it to Crow Foot, saying, “This boy wants to know how he will make a living.” Crow Foot went to a white boarding school at the Standing Rock reservation, but he had little use for white ways. In 1890, Sitting Bull prepared to travel to the Pine Ridge reservation to find out more about the Ghost Dance, a new religion that he hoped could revive the old Indian ways. The Indian agent at Standing Rock ordered forty policemen to stop him. Heavily armed, they burst into the family’s home at dawn. Crow Foot, then fourteen, urged his father to resist. Minutes later, both father and son were shot dead.

In June, his father came for him and he returned home. Riding through the desert on the burro, he thought about what he had learned in his two years of white education: “I had learned many English words and could recite part of the Ten Commandments. I knew how to sleep on a bed, pray to Jesus, comb my hair, eat with a knife and fork, and use a toilet. I had learned that the world is round instead of flat, that it is indecent to go naked in the presence of girls … I had also learned that a person thinks with his head instead of his heart.”

He went home for the summer and helped his father hoe weeds and tend sheep. As the third school year approached, Chuka’s grandfather worried that Chuka was losing his Hopi ways. The old man reminded him to spit four times if he had bad dreams while at school. That would drive evil influences from his head. One morning in September, Chuka was preparing to set off for school when armed police appeared and surrounded his village.

“Their intention was capturing the children of Hostile families and taking them to school by force. They herded us all together at the east edge of the mesa. Although I had planned to go later, they put me with the others. The people were excited, the children and the mothers were crying, and the men wanted to fight. I was not much afraid because I had learned a little about education … The next morning we took a bath, had our hair clipped, put on new clothes and were schoolboys again.”

Throughout his life he struggled to live in two worlds. He took the name Don Talayesva for whites but kept his Indian name and belief in Hopi customs. He was such a good student of English that he was able to co-write his autobiography. He lived to be an old man and stayed in his village of New Oraibi. When his uncle died, Chuka became a tribal official. He married and had four children. To his great sorrow, each of them died as a baby.

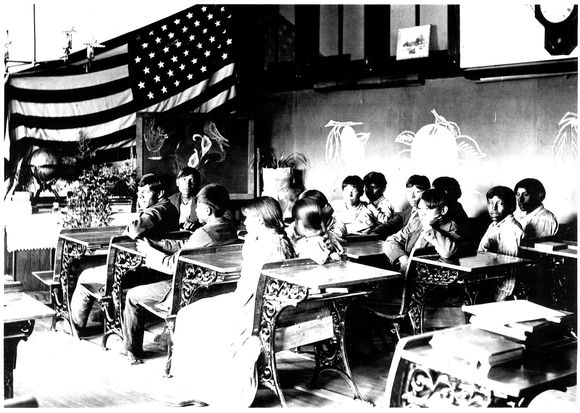

A classroom at the Riverside Indian School at Anadarko, Oklahoma, in 1901