“I am the new feller hand.”

Russia and New York City, 1892

Rose Cohen grew up in a tiny Russian village where Jewish life was brutally controlled by the army of the czar. Jews were forced to live within a barren region that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Rose’s father fled to America, bribing troops at the border to let him pass. Rose heard nothing more from him until the day in 1892 when she received a package covered with mysterious stamps. Inside were two steamship tickets to America—one for Rose, then twelve, and one for her aunt, a few years older. Her father sent for Rose first because he had taught her to sew. She could help him make enough money in New York to send for the others. Rose’s father met her ship in New York City and then led her to their new home—a grimy tenement on the Lower East Side. Like many immigrants before and after them, father and daughter vowed that they would work hard so that next year at that time the family would all be together. Rose Cohen wrote of her first two days in a New York sweatshop.

A SINGER SEWING MACHINE

In the 1870s, the first Singer sewing machines reached Russian Jews. Twenty years later, more than fifty thousand Jewish girls and women worked in the sewing trades. Each small Russian town had little shops where several Jewish women labored over the Singer machines, making clothing. Girls were usually apprenticed to a seamstress at the age of thirteen. Mastering the sewing machine was hard, but it was worth it. Because they had a moneymaking skill, these girls were often the first in their family, perhaps after one parent, to come to America.

European immigrants like Rose Cohen bundled all their belongings onto ships like this one bound for America.

A CLOCK THAT CALLS

“Often I get there soon after six o’clock so as to be in good time, though the factory does not open till seven. I have heard that there is a sort of clock that calls you at the very time you want to get up, but I can’t believe that because I don’t see how the clock would know.”

—Sadie Frowne, sixteen, a sweatshop worker born in Poland

About the same time that the bitter cold came, father told me one night that he had found work for me in a shop where he knew the presser. I lay awake long that night. I was eager to begin life on my own responsibility but was also afraid. We rose earlier than usual that morning for father had to take me to the shop and not be late for his own work. I wrapped my thimble and scissors, with a piece of bread for breakfast, in a bit of newspaper, carefully stuck two needles into the lapel of my coat and we started.

“The shop was on Pelem Street, a shop district one block long and just wide enough for two ordinary sized wagons to pass each other … Father said, ‘good-bye’ over his shoulder and went away quickly. I watched him until he turned onto Monroe Street.

“I found a door, and pushed it open and went in. A tall, dark, beardless man stood folding coats at a table … ‘Yes,’ he said crossly. ‘What do you want?’

“I said, ‘I am the new feller hand.’ He looked at me from head to foot. My face felt so burning hot I could scarcely see. ‘It is more likely,’ he said, ‘that you can pull bastings than fell sleeve

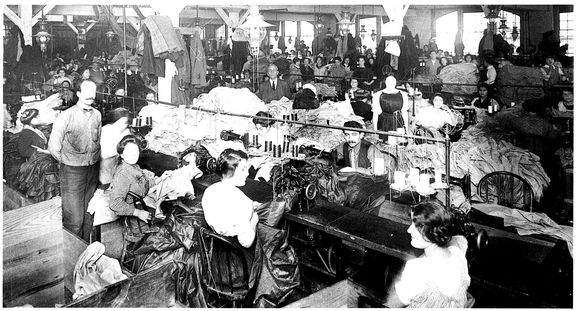

A sweatshop on New York City’s Lower East Side

lining.’ Then turning from me he shouted over the noise of the machine: ‘Presser, is this the girl?’ The presser put down the iron and looked at me. ‘I suppose so; he said. ‘I only know the father.’

“The cross man said, ‘Let’s see what you can do.’ He kicked a chair, threw a coat upon it and said, ‘Make room for the new feller hand.’ One girl tittered, two men glanced at me over their shoulders and pushed their chairs apart a little … All at once the thought came, ‘If I don’t [sew] this coat quickly and well he will send me away at once.’ I picked up the coat, threaded my needle and began hastily, repeating the lesson father impressed upon me: ‘Be careful not to twist the sleeve lining, take small false stitches.’”

The man inspected the sleeve and then silently tossed Rose two other coats to sew. She reached her apartment well after dark. She went back out the next day before the light of dawn. Everyone was already at their stations. The boss bawled her out for being late. This is not an office, he told her. She bent down low and began to work.

“From this hour a hard life began for me. [The boss] refused to employ me except by the week. He paid me three dollars and for this he hurried me from early until late … He was never satisfied. By looks and manner he made me feel that I was not doing enough. Late at night when the people would stand up and begin to fold their work away … he would come over with still another coat. ‘I need it first thing in the morning; he would give as an excuse. I understood that he was taking advantage of me because I was a child. And now that it was dark in the shop except for the low single gas jet over my table and the one over his at the other end of the room, and there was no one to see, more tears fell on the sleeve lining than there were stitches in it.

“[When I got home] my father explained, ‘It pays him better to employ you by the week. Don’t you see if you did piece work [and got paid for each coat] he would have to pay you as much as he pays a woman piece worker? But this way he gets almost as much work out of you for half the amount a woman is paid.’

“I myself did not want to leave the shop for fear of losing a day or even more perhaps in finding other work. To lose half a dollar meant that it would take so much longer before mother and the children would come … Often as the hour for going home drew near I would make believe they were home waiting. On leaving the shop I would hasten along through the street keeping my eyes on the ground so as to shut out everything but what I wanted to see. I pictured myself walking into the house. There was a delicious warm smell of cooked food. Mother greeted me near the door and the children gathered about me shouting and trying to pull me down. Mother scolded them saying, ‘Let her take her coat

SWEATSHOPS

Clothing workers filled factories called sweatshops on New York’s Lower East Side. Workers made dresses and shirts and coats in an assembly line, the way cars are made. A worker finished one part and then passed the garment on to the next worker. A boss stood behind, nagging. Most workers smoked, so a thick blue haze hung over the shop. A peddler brought in beer and whiskey from time to time. Some Jewish women sang songs in Yiddish as they worked, but always, always they bent over their garments.

THE TRIANGLE SHIRTWAIST FIRE

On March 25, 1911, a fire exploded at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory in New York City. Trapped behind locked doors were hundreds of teenage girls and young women—mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants. The fire department arrived quickly, but their ladders could reach only to the sixth floor of the ten-story building. Girls leaped from the higher floors and tore through the safety nets. One hundred forty-six were killed. The tragedy led to increased union activity among garment workers.

off, see how cold her hands are!’ I used to keep this up until I turned the key in the door and opened it and stood facing the dark, cold silent room.”

She kept working in shops and helped make enough money to send for the rest of her family. She became a union leader and organizer. She refused to marry a man her father had picked for her and later married Joseph Cohen. When their daughter Evelyn was born, Rose stopped working in sweatshops. She took writing classes and followed her passion, writing. She wrote five short articles and a book about her life. All were praised. She died in 1925.