“We are not just fighting for ourselves, but for decent conditions for workers everywhere.”

Pullman, Illinois, 1893—1894

George Pullman invented a luxurious sleeping car for railroad passengers. His company took off in 1865, when a Pullman car was attached to the funeral train carrying Abraham Lincoln’s body. After that, Americans dreamed of riding in style. Pullman built an entire town near Chicago for the workers who manufactured his cars. He seemed to take care of their every need. But when the company’s fortunes sagged, life for a Pullman worker became brutally hard. One fearless teenage girl sparked a demand for justice in one of America’s most famous strikes.

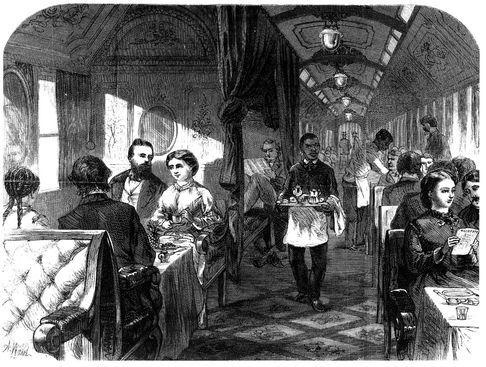

Inside a Pullman Palace Car. For a few dollars more, one could cross the prairie in style, sleeping on a pul/-down bed and eating good meals served on white linen tablecloths.

Jennie Curtis started life in a squalid Chicago tenement with her parents and little sister. Her father, Alexander Curtis, could barely make enough as a peddler in Chicago’s downtown streets to keep them alive. And then one evening he came home red-faced and talking fast. A dream had come true! He had a new job with the Pullman Palace Car Company, the one that made fancy railroad cars. They were moving to Pullman Village, the new town Mr. Pullman had built just for his workers. Now they would live in a two-story house with a private entrance and a backyard. There would be hot and cold running water and gas for cooking. Every day someone would come to pick up the garbage!

Pullman Village was amazing. There were theaters, a library, and a hotel—all just for the Curtises and their neighbors. They chose the biggest and most expensive of the three kinds of houses offered, even though the rent ate up nearly half of Mr. Curtis’s paycheck and meant he had to work nearly all the time he was awake. Jennie’s mother made the children’s clothes to save money and they planted a vegetable garden.

Jennie liked Pullman well enough, but she knew it wasn’t a paradise. The company controlled everything. It set the prices everyone had to pay for food, rent, and heat. Living in Pullman was more expensive than in Chicago, and there were company spies everywhere. Mr. Pullman kept calling the residents his “children.”

Jennie went to work for Pullman when she was thirteen. At first she worked in the room where they sewed fancy carpets and draperies for the sleeping cars. The work was

boring. She hated the long hours, but the pay was good—$2.25 a day. She kept telling herself that she was making good wages for a girl.

But in 1893, the American economy collapsed and orders for luxury railroad cars dropped. Pullman slashed everyone’s wages again and again, but his rent and prices for heat and food stayed high. Children walked barefooted through his wide streets, and the big houses turned cold when renters couldn’t afford heat. Jennie’s wages were cut twice in a single week. Soon she was making only eighty cents a day. When she complained, she was transferred to the repair shop, where it was even harder to make good money.

One of the seamstresses was assigned to supervise the others. The woman seemed to change overnight with her new authority. Jennie wrote: “She had sewed and lived among us for years … You would think she would have compassion on us … [but] she seemed to delight in showing her power in hurting the girls in every possible way … She was getting $2.25 a day and she did not care how much we girls made, whether we made enough to live on or not, just so long as she could figure how to save a few dollars for the Company.”

Jennie organized a petition to have the supervisor removed. After fifteen of eighteen girls and women signed it, Jennie took it to the superintendent. He ignored it, but he began to look at Jennie Curtis as a troublemaker.

Then Jennie’s world collapsed. Her father died after a long illness. Alexander Curtis had worked for Pullman for thirteen years. The company reacted by informing Jennie that her dad still owed them sixty dollars for rent and it was up to her to pay it. They would be taking money from her weekly paycheck until the debt was paid. At first she tried to keep up the payments, just so her family could stay in their house, but it got to be too much. Trips to the bank grew ugly. Jennie wrote: “When I could not possibly give them anything, I would receive slurs and insults from the clerks in the back, because Mr. Pullman would not give me enough in return for my hard labor to pay the rent for one of his houses and live.”

Jennie’s co-workers depended on her more and more as times got worse at Pullman. They recognized her as a leader. She kept her cool under fire even when she was angry. Though she was young, she always seemed to find the words to express what they all felt. Many Pullman workers were signing up for the American Railway Union (ARU), led by a brilliant organizer named Eugene V. Debs. The Pullman company hated the ARU, which threatened its control. At first Jennie wasn’t convinced they needed a union at Pullman. She thought the company might still listen to reason. In May of 1894, she and four other leaders went to see the company superintendent, Thomas Wickes, in his paneled office. They demanded the company either restore their full pay or cut rents in Pullman Village. Wickes barely looked up from his desk. Three of the five workers were fired after the meeting. Jennie was allowed to keep her job, perhaps because she still owed the company money.

PULLMAN PALACE CARS

Suppose you need to travel from Omaha to Sacramento in 1875. You could pay forty dollars and sit on a hard bench for most of a week. You could pay seventy-five dollars for a little more room, but you would still be eating stringy buffalo steak for dinner. Or—for just four more dollars a night—you could ride in a Pullman Palace Car. Now, when dinnertime comes, your waiter unfolds an embroidered white tablecloth and serves you fresh trout with lemon and melted butter. After dessert he lights the reading lamp and you settle in with a good book while people gather round the organ and sing. You hum along until you become drowsy, and then fold your seat down into a soft bed and pull your curtain around you. You douse the light and watch the moon gleam on the rails until prairie dreams overtake you.

DEEP FEELINGS

When George Pullman died, in 1897, he was so hated by his employees that his heirs feared his body would be stolen. His coffin was covered in tar paper and asphalt and placed in the center of a room-size cube of concrete, reinforced with railroad ties. Then the entire “room” was buried thirty feet beneath the ground.

The very next day Jennie signed her American Railway Union card and was quickly elected president of the Girls’ Union, Local 269. Only eighteen, she now spoke for thousands of women at Pullman. Jennie and other union leaders went to Chicago in June to urge the ARU to support the Pullman workers in a strike against the company. Thin and tired, Jennie stood up in a downtown union hall and addressed 450 ARU delegates. The room fell silent as she explained that some of the women in her sewing room were starving. Tough men wept as she told the story of her father’s death and the unpaid debt. When she finished, one of the ARU delegates leaped up and urged a strike. A roar of approval filled the hall. But Debs urged caution. The ARU, he pointed out, was only one year old and still fragile. A loss might further weaken them, and he wasn’t convinced they could win against the wealthy railroad managers. Then Jennie rose again to face the delegates. “We ask you to come along with us,” she pleaded, “because we are not just fighting for ourselves, but for decent conditions for workers everywhere.”

At Debs’s urging, the Pullman workers tried twice again to negotiate with the company. It was no use. So they stopped work, and fifty thousand railroad workers throughout the nation joined them. Engineers refused to drive trains carrying Pullman cars. All traffic on the twenty-four railroad lines going out of Chicago stopped. With no cars moving, Pullman’s business ground to a standstill. George Pullman himself asked the mayor of Chicago and the governor of Illinois to send police to force the workers back to work. Both refused.

But President Grover Cleveland felt differently. Declaring that the U.S. mail had to keep moving, he sent thousands of federal troops to Illinois. Riots broke out. Thirty strikers were killed and hundreds injured. A federal judge declared all strike activity illegal. Union leaders were arrested, and Eugene Debs was imprisoned. The Pullman strike collapsed in August and the factory reopened, minus one thousand union members who had been fired for taking part in the strike.

Six hundred freight cars burn on the Panhandle Railroad, July 6, 1894, as striking railroad workers battle federal troops.

All record of her life after the strike seems to have disappeared. She was probably fired because she was a well-known union member and strike leader. Maybe she changed her name so she could get another railroad job somewhere else. In 1994, there was a gathering in Chicago to honor the one hundredth anniversary of the Pullman strike. Historians scrambled to find any record of the girl whose words had jolted the ARU convention back to life and sparked the strike. All efforts failed. One wrote in tribute, “Perhaps if we try hard enough, we can feel her spirit on this centennial.”