“Be a good boy and cry.”—Jackie Cooper’s grandmother

Hollywood, California, 1930

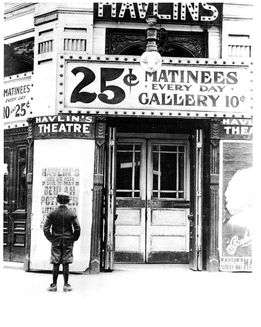

On April 23, 1896, a few people in a New York City music hall saw the first exhibition of motion pictures in the United States. Ten years later, small, shabby theaters called nickelodeons had sprung up all over the country to gobble the nickels of working children. The boys and girls sat in the dark, biting off chunks of gooey candy, as adventure stories passed before their eyes. By 1911, 16 percent of all schoolchildren in New York City saw at least one movie a day. Hollywood talent scouts combed the country for children who could act. One was a quick-thinking boy with a mop of blond hair named Jackie Cooper. His big break came in 1930, when, at the age of eight, he beat out three hundred other children for the lead role in a movie called Skippy. The fun ended when it was time for him to cry.

AT LAST, MONEY OF THEIR OWN

“Never before have such numbers of young boys earned money independently of the family life, and felt free to spend it as they choose.”

—Jane Addams, 1909

“My first crying scene came at the end of a long, hard day. [The director] told everyone on the set to be quiet. My grandmother said, ‘Be a good boy and cry.’ They waited. I tried. No tears …

“The director screamed, and he hollered. He shouted that it had been a mistake to have hired me and he called me a ‘lousy ham actor.’ He told his assistant to start getting the standby kid ready to replace me … It made me angry rather than unhappy. Angry kids don’t cry … I hit things and slammed things and maybe even broke things but not one tear was shed.

“As I waited, I saw a new figure on the set, another kid dressed exactly as I was dressed, in the Skippy costume. They always have two of everything on a set, and they had quickly put it on one of the other kids … The idea that they would give my part to another boy was enough to make me very sad very quickly.

“I came apart at the tear ducts. I really cried … They rushed me into the scene, and I did it, and then they gave me an ice cream cone, and [the director] said I was a fine actor, and my grandmother said I was a good boy.”

Jackie Cooper got bigger and bigger parts. As a ten-year-old he was earning more than the president of the United States. But later he felt he had paid a price:

“I had no friends. I did not receive a good education. I grew up with pressure and responsibility from the time I was seven or eight. The pressure to get the scene right, to learn the words, to act this way or that way, to smile or cry or look scared for the cameraman, to do a nice interview … Why should an eight-year-old kid have that kind of pressure?”

And adults controlled the money. In 1921, a seven-year-old actor named Jackie Coogan (a different boy from Jackie Cooper) got the title role in a film called The Kid and soon was earning nearly $10,000 per week. When he turned twenty-one, he tried to claim some of the $4 million he had earned as a boy. Lawyers told him he had no right to it. He sued to win his salary, but the courts always ruled that money he had earned when he was a minor belonged to his parents. He won in the end, and other child actors with him. The California State Legislature passed the Child Actors Bill, which said that at least half of a child actor’s earnings had to be set aside in a fund that could be claimed when the actor turned eighteen.

He went on to become a well-known actor and a director of the long-running television series M*A*S*H.

Jackie Cooper (left) and Jackie Coogan star together.