SELLING THE WAR

To excite the American people about the war, President Wilson set up the Committee on Public Information and hired an advertising executive to run it. Speakers gave rallying speeches across the country and made up slogans that encouraged families to conserve food. One went, “Don’t let your horse be more patriotic than you are—eat a dish of oatmeal.” Referring to German submarines, another cautioned, “If U fast U beat U boats—if U feast U boats beat U.” Teachers went along, assigning essays about such things as the tastiness of potatoes. Life magazine advised parents, “Do not permit your child to take a bite or two from an apple and throw the rest away … Children must be taught to be patriotic to the core.”

“I hung at the back of the crowd, watching with distaste as the grownups made fools of themselves.”

Hamburg, Iowa, 1914—1918

Eight-year-old Margaret Davidson lived in a small Iowa town during the final year of World War I. The war caused trouble in her town that was even more upsetting than the fighting overseas. The problem seemed to revolve around the word patriotism. To some, it meant supporting American soldiers and making sacrifices for the Allied cause. But to others, the word meant making life miserable for the German-Americans in Hamburg. Margaret later wrote about the forces that tore apart Hamburg, Iowa, during the Great War.

When America entered the war in 1917, the citizens of Hamburg, Iowa, exploded with patriotic activity. Red Cross chapters rolled miles of bandages, knit khaki sweaters and socks, and made flannel nightgowns. “As the draft board began calling up and sending off our young men … we students learned all four verses of the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and sang them every morning along with ‘The Marseillaise’ (which had one verse in English) and ‘God Save the King.’ We sang patriotic songs reaching all the way back to the Civil War—and also ‘Tipperary’ and ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’ and ‘Over There.’ Surely no group of kids ever knew so many patriotic songs as we.”

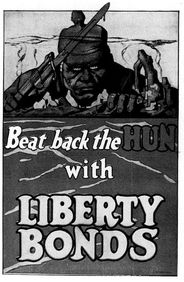

German soldiers were drawn as beasts in many World War I posters.

Like Americans everywhere, the Davidsons went without food and coal so that they could be sent overseas. They learned to cook without sugar or flour. They even followed the government’s advice and “Fletcherized” their food, chewing each bite thirty to forty times before swallowing. Supposedly, Fletcherizing let them

eat less, save more for the troops, and still squeeze the full nutritional value out of each bite. Margaret thought it was crazy, but she remembered the soldiers and dutifully chewed away.

Boys at a Cooperstown, New York, school knit blankets for World War I soldiers.

The Davidsons sat through endless speeches at Liberty Bond rallies to raise money for the war. Margaret followed battle reports in the newspaper and felt heartsick when she read that a soldier from Hamburg had died, especially if she knew his brother or sister. But she was troubled even more by a conflict brewing right in Hamburg.

One large group of men was trying to use the overseas war against Germany to turn townspeople against their neighbors of German ancestry. Some of the men were outlaws who had settled in Hamburg because it was conveniently close to both the Nebraska and Missouri borders if Iowa authorities came after them. They made speeches declaring that no German-American could be trusted and accused anyone who disagreed with them of being unpatriotic. Unfortunately, that included Margaret’s father, who published the town newspaper.

“HYPHENATED AMERICANS”

World War I made things much harder for millions of European immigrants in the United States, especially those who came from enemy lands. Former president Theodore Roosevelt led the attack on what he called “hyphenated Americans,” mainly German-American and Austrian-American residents. “They play the part of traitors,” Roosevelt declared. “Once it was true that this country could not endure half American and half slave. Today it is true that it cannot endure half American and half foreign. The hyphen is incompatible with patriotism.”

To Margaret’s dismay, anti-German fever spread rapidly. Early in 1917, a mob attacked Hamburg’s German Lutheran church, smashing the windows and smearing the sanctuary with yellow paint to symbolize cowardice. “Only a few people were shocked or indignant at this incident,” Margaret wrote with alarm. German dolls—her favorites—were pulled from store windows. German classes were banned in the high school, where students heard horror stories of German atrocities in Belgium and France. Younger children were taught to hate the kaiser.

Soon the town was deeply divided. Many remembered that German immigrants had founded and built Hamburg the century before, naming it after a German city. Margaret didn’t see why their descendents still living in town couldn’t be both patriotic Americans and citizens proud of their German heritage. One fall day in 1917, she took a small stand of her own against intolerance:

“When I went home for lunch, I heard that some super-patriot had the bright idea that all the German books in the town should be burned in a public bonfire. My sister Letha was away at college. She had studied German four years in high school and owned a half-dozen or so German books. I hid them where my mother couldn’t find them. I had a strong feeling that these books belonged to Letha and that it was for her alone to decide what to do with them. The bonfire blazed in a vacant lot across from the post office. A large crowd waved flags, yelled and danced as they threw more books into the fire. I hung at the back of the crowd, watching with distaste as the grownups made fools of themselves.”

A NATIONAL DRAFT

After declaring war, President Wilson called for a million men to volunteer, but six weeks later only seventy-three thousand had signed up. So, in May of 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, allowing the armed forces to draft young men into the military whether they wanted to serve or not. It was the first time in U.S. history that young men were drafted into a national army. Blacks were drafted, but only about one-tenth of those who served were allowed to fight. Most performed food and maintenance work.

Senators debated the proper draft age. Said Senator Nelson of Minnesota, “Make the age limit eighteen. If you want good soldiers, take the young men.” Senator Lodge of Massachusetts countered, “A boy of eighteen is still in the growing stage.” The age was first set at twenty-one but quickly lowered to eighteen as more troops were needed. Most reported to their draft boards, but many others did not—risking a year in jail. The government encouraged neighbors to report so-called slackers and tried to shame them into induction with poems like this one, which took the stern voice of a father:

I’d rather you had died at birth or not been born at all

Than know that I had raised a son who cannot hear the call

To save the world from sin, my son, God gave his only Son

He’s asking for MY boy today, and may His will be done.

Another poet gave a different view:

I love my flag, I do, I do, which floats upon the breeze

I also love my arms and legs, and neck and nose and knees

One little shell might spoil them all and give them such a twist

They would be of no use to me; I guess I won’t enlist.

On November 7, 1918, word reached Hamburg that an armistice had been signed and the war was over. Jubilant people poured out of their houses to share the

news with their neighbors. “Someone played ‘America’ on the steam whistle at the light plant. And yet, some people weren’t quite sure it was true. They were right—it wasn’t.”

It was a false alarm, but soon definite news arrived that the war in Europe would cease at 11 A.M. on November 11. Europe may have been at peace, but Hamburg wasn’t.

“I didn’t hear about it until I got to school, where we were told that school would be dismissed at 11 A.M. We were crazy with excitement. The teachers lined us up ten abreast and prepared us to march down the school house hill singing ‘Columbia the Gem of the Ocean.’ Then I was looking for a wild and wonderful day with my Dad who always took me with him to exciting events. Suddenly, from nowhere, he appeared and snatched me roughly from my line and pulled me over to the edge of the street. He said, ‘I want you to go right home and don’t go out of our yard again today no matter what happens.’” Then he disappeared.

It turned out that Margaret’s father was trying to protect a store owner who refused to close his store at eleven o’clock. The man insisted upon waiting until noon. Some of the “super-patriots,” as Margaret called them, were so angry that they had already smeared his store with yellow paint and were looking around for a rope to lynch him. Margaret’s father was one of only four men in town trying to save the storekeeper’s life.

The standoff lasted the whole day, paralyzing the center of town and ruining Hamburg’s victory celebration. After dark, Margaret’s father came home, explaining that the men had finally gotten tired and gone home to bed. That suited Margaret just fine. She was tired too—tired of living in a divided, angry town. “By midnight the streets were nearly clear,” Margaret wrote. “Peace descended on Hamburg. The War was over.”

She went to college and, like her mother, became a librarian. During a long career she worked in three Iowa public libraries. Margaret died in 1984.

“WHY DID GOD SEND THE EPIDEMIC?’

One spring day in 1918, Margaret Davidson found herself at the funeral of three of her classmates—all from the same family. A week later, four from another family died. The Spanish influenza had struck Hamburg. Children made up a rhyme for it: “I had a little bird, its name was Enza. I opened up the window, and in-flew-Enza.” It was a mystifying plague that raced through the world, killing twenty million people in less than a year. The flu swept through the army camps of World War I, killing soldiers so fast that doctors stacked up their bodies like wood. Doctors couldn’t see the flu virus in their microscopes and wondered why everyone was dying. Some thought it was a German plot. With no vaccine, people stayed home, wore masks, and tried to breathe only through their noses. Nothing worked. Schools, theaters, church services, and other public gatherings were stopped in most U.S. cities. The crisis ended when the disease vanished just as mystifyingly as it had appeared.