SO LONG (IT’S BEEN GOOD TO KNOW YUH)©

A dust storm hit, it hit like thunder,

It dusted us over and it covered us under;

Blocked out the traffic and blocked out the sun;

Straight for home all the people did run, [saying,]

So long it’s been good to know ye

This dusty old dust is a-getting my home

And I’ve got to keep drifting along.

—Oklahoma-born songwriter Woody Guthrie, 1940

“It was coming too fast to be a thunderstorm.”

Near Dodge City, Kansas, 1935

Years after it ended, World War I darkened the skies of Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas. Farmers had answered the call to “win the war with wheat” by plowing under native grasses and planting wheat to feed the soldiers. The strategy led to an environmental disaster. A drought began in 1931 that lasted for nearly ten years. Windstorms swept up the soil that had once been held together by deep-rooted grasses and whipped it into black, towering clouds. The Great Plains simply blew away. Noon seemed like midnight when the dust flew. The worst storm of all hit on April 14, 1935, producing a terrifying cloud seven thousand feet high. That noon, thirteen-year-old Harley Holladay had just gone outside to enjoy a rare day of fresh air on his family’s Kansas farm.

“It was such a nice clear Sunday. We had hung the laundry out on the line that morning, and mother had washed the upholstered chairs and set them out to dry. I walked up to our horse pond and had picked up a stone to skip across the water. While I was throwing I happened to look up and noticed this long gray line on the horizon. It looked like a thunderhead, but it was too long and flat and it was rolling toward me way too fast. I sprinted to the house to tell my parents that the dust was coming but they wouldn’t believe it until they went outside and looked for themselves. Then we started hauling in clothes as fast as we could, just snatching them in armloads and running. The cloud caught me outside with a load of clothes. I couldn’t see anything at all. It was black as night. I got down on my hands and knees and tried to crawl toward the house. I finally felt the porch, and reached up and opened the screen door and crawled inside.

Throughout the 1930s, winds swept the powdery soil of the Great Plains into towering “black blizzards.” Kansas farmers joked that they could see Texas and Oklahoma whizzing past their windows.

“For a long time it was total blackness inside, except for one thing. When I looked out the window I could see

our radio antenna outlined in static electricity. There were little balls of fire all over it caused by dirt particles rubbing together. It was spooky. Finally the sun began to shine as a faint glow of orange light coming in through the windows. As it got lighter, I could see baskets and brush sailing past us. It felt like we were flying through space.”

When the storm was over they stepped outside. Dust was heaped in the yard like sand dunes in a desert. Cattle and farm equipment were buried. Jackrabbits loped through the dunes. As always, Harley and his family cleared their throats and dug out.

“I guess we had gotten used to it, because it had been that way for a long time. Our windows were taped up and the cracks in our walls were stuffed but nothing kept the dust out. Whenever we ate a meal we had to turn our plates and cups and glasses over until the exact time the meal was served. Even then, you could write your name in dust on your glass by the time the meal was done. Every night before we went to bed we scooped a little water into our noses and blew out the dirt. We put covers over our faces and a sheet over my little sister’s crib. Some people slept with masks on.

CALIFORNIA BOUND

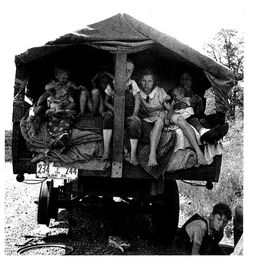

During World War I, the government had set a very high price for wheat, and many farmers made more money than ever. They used their profits to buy more and more land to plant more and more wheat. But after the war ended, the price of wheat declined, a situation made worse when it stopped raining in 1931. With no crops to sell, many families couldn’t keep up their bank payments and lost their farms. More than three million people, like the Arkansas family shown here, left the Great Plains in the 1930s and headed for California, looking for a better life. Most Dust Bowl families were met with hostility and scorn.

“You didn’t want to get caught out in a storm, either. Some families strung clothesline between the house and the barn so that they could always find their way back to the house. We always made sure we had food and water with us when we left the house. When the dust started flying and I was away from the home I tried to find a fenceline to follow. My father used my brother and I as guides when he was plowing with the tractor in the fields. I’d stand at one end of the field with a kerosene light and my brother would shine a light at the other end. My dad would try to drive straight between us. The dust came so fast that it would cover up the tractor’s tracks.”

At the end of a workday their clothes were caked, their hair was matted, and their skin was streaked with dust. They bathed in a tub on the porch before they entered the house, but

nothing kept the dust out. No matter what they did, the rain stayed away, the soil blew away, and very little grew. In 1935, the government established the Soil Conservation Service. The aim was to encourage Dust Bowl farmers to plant grass, rotate their crops, plow the land into strips that caught rainwater, and plant rows of trees to break up the wind. It helped, but true relief didn’t come until rain finally came—five years later. By then, Harley Holladay was a soldier in Italy.

“I was in World War II when the rain came back to Kansas, but I was still thinking a lot about the farm. One night in Italy I had the most wonderful dream. I was back on the farm in Kansas and we were having a rainshower at last. It was a big, loud thunderstorm, with buckets of rain just soaking the ground. I was so happy. And then someone was shaking me awake and there were tracer bullets and anti-aircraft fire all around. We were under attack. But in my dream the thunder of gunfire was a great blessing. That’s how much rain meant to a Dust Bowl boy.”

After World War II, he farmed his family’s land for twenty years. Then he became a husband, a father, a potter, a brickmaker, a research scientist, a schoolteacher, a tour guide, and an actor, and he drilled a few oil wells along the way. “I was one of those guys who never settled down,” he says.