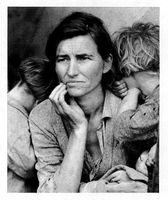

Peggy Eaton, age fifteen

“You’ll be back for supper!”—Peggy Eaton’s father

Wyoming, Idaho, and Washington, 1938

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, nearly one-third of all working-age Americans were out of work. Many teenagers left home to hitchhike and ride freight trains around the country. Their reasons varied: Some schools were closed and there was little work to be found. Some, like sixteen-year-old Clarence Lee, were told by their parents, “Go fend for yourself. I can’t afford to have you around any longer.” Fifteen-year-old Peggy Eaton left her home on a Wyoming ranch in the summer of 1938, after an argument with her father.

“The real problem was there was just no money. I was going into my junior year in high school and I wanted decent clothes to wear when school started … I was taking care of sheep for my brothers, and milking cows for my dad, but it just didn’t look like I was going to make any money. I was mad a lot that summer.

“One night the cow I was milking whopped me in the eye with her dirty tail. I got up and whopped her right back with my stool and cussed her out. My dad heard me. He came over, boxed me up one side of the face and down the other. He said, ‘Don’t you ever let me hear you talk like that again!’ I said, ‘I’ll leave home!’ He said, ‘You’ll be back for supper!’

“A couple of weeks later my friend Irene asked me if I wanted to go with her to see her folks in Issaquah, Washington. She said I could make lots of money out there picking fruit. I didn’t tell my folks. I just rolled up a few pieces of clothing and tied it with rope and slung it over my shoulder. Irene stuffed her things in a suitcase made of tin. We took off hitchhiking on July 12.

“The first day we got rides all the way to Cokeville, Wyoming, near the state line with Idaho. We were walking down the highway when we came to a railroad yard. There were two out-of-work bums cooking their dinner in an old gallon bucket over a campfire. They asked if we were hungry and of course we said yes. They served us a nice vegetable stew and coffee out of tin cans. They said their names were Joe and Slim. They were going to Washington, too, and they said we’d do better riding the rails than trying to hitchhike.

“Soon a train stopped to water up and we all four climbed into an empty freight car. Slim and Joe showed us a lot of things about riding. They warned me not to swing my legs out the open door because they could get caught on a railroad switch and pulled right out. When night came and the cold came in, they showed us how to roll up in the paper that lined the walls of the boxcar.

“Two days later we jumped off at Nampa, Idaho. Slim and Joe went off to beg for food, and Irene and I walked over to a grassy area where dozens of hobos were living. Everyone had their eyes on this one boxcar door, the only open door on a train that was about to leave for La Grande, Oregon. Every hobo in that yard wanted to get inside that car. The bulls [railroad police] were patrolling the area with rifles and lanterns. Everyone was a little nervous because the day before one of them had shot a bum off the top of a boxcar in the La Grande freight yard.

“When the engine started up a wave of bums rose up like one person and rushed for that open door. I was the first one there. Someone behind me picked me up by the nape of the neck and the seat of the pants and pitched me into the car. Irene was right behind me. It was dark inside, and scary. We were the only girls. We crawled into a corner and Irene put her tin suitcase in front of us. Slim and Joe made it on board and slept in front of us, too, that night.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

During the 1920s, Americans went on a spending spree—eagerly snapping up newly invented automobiles and household appliances on credit. Businesses made huge profits, and common people invested in these businesses by buying their stocks. But as company profits soared, the average worker’s pay rose very little. A rapidly widening gap arose between the number of things available to buy and the workers’ ability to keep up with payments. Families struggled beneath a mountain of debt.

On Tuesday, October 29, 1929, the stock market crashed, triggering the Great Depression, the worst economic collapse in the history of the modern world. One-quarter of all American workers lost their jobs, and farm families like Peggy Eaton’s suffered when customers had little money to buy meat and produce. President Herbert Hoover assured Americans it would be over in sixty days. In fact, recovery took more than ten years.

THE CCC

In 1933, the government set up the Civilian Conservation Corps—or CCC—to provide work for the millions of boys and young men, aged seventeen to twenty-three, who were not in school and had no jobs. By 1940, more high school graduates were joining the CCC each year than were enrolling in America’s colleges. CCC workers made thirty dollars a month. They lived in racially segregated camps and did hard outdoor work. They built roads, trails, and bridges; fought fires; staked out fences; blazed trails; dug wells; and planted forests. By the time the program closed in 1942, CCC workers had planted more than half the trees in the nation.

“When we got near the La Grande freight yard the train sped up instead of slowing down. It looked like a trap, especially since it was the same place where the bull had shot the man the day before. We went for the door and jumped out while the train was going at least thirty-five or forty miles an hour. I tumbled head over heels when I hit the ground.

“We couldn’t catch a freight out of La Grande because the bulls were too thick so we split from Slim and Joe and went back out on the highway and caught a ride in a gasoline truck. The old road took us over what was called ‘Cabbage Hill’ between La Grande and Pendleton. We reached the top of the hill right at sundown. There were hundreds of little farms, in all different colors spread out before us. I had never seen anything so magnificent in my life.

“We hitched into Pasco, Washington, found a room for a dollar and then walked down to the tracks the next morning. The only available boxcar was full so we climbed up onto the top of the train and rode up on the catwalk, where railroad workers can walk across the top of the train. When the train first got going we were scared to death and clung tight to the edge, but soon we were sitting up and looking around at the desert. Suddenly we saw a man coming toward us on the catwalks, jumping from car to car. When he reached us he sat down to visit. He was a bull all right, but sort of a friendly bull. He didn’t know how to roll a cigarette so we rolled it for him. He told us we’d have to get off in Yakima, because after that there were low tunnels through the Cascade Mountains and he didn’t want to see us get decapitated.

“So we got off at Yakima. When we finally made it to Irene’s home in Issaquah she came down with the mumps. We started back east as soon she got well. We never did pick fruit or make any money.

A CHILD LABOR LAW AT LAST

At a time when there were very few jobs for anyone, Congress finally passed a law to protect children from working. The Fair Labor Standards Act, passed in 1938, prohibited employment of any child under fourteen, except for farmwork, and all children under sixteen while school was in session. The National Association of Manufacturers, now denied an abundant source of labor, called the law a “communist plot” and tried to get the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn it, but the act held. It was soon amended to protect child farmworkers under sixteen, but in 1950, a congressional commission reported that 395,000 children between ten and fifteen were still working on farms. This trend continued throughout the twentieth century.

“Going back east people were less generous. In Nampa, Idaho, we got arrested for vagrancy, fingerprinted and thrown into a dirty jail cell. The next morning the judge fined us ten dollars apiece, but instead of making us pay he wrote us out a voucher for a free breakfast and a personal note that said, ‘Eat your breakfast and get out of town.’ That was fine with us.

“We went on to Soda Springs, Idaho, where there was a rodeo. A couple of cowboys who had pitched their tent in the city park shared a pot of beans with us. They let us use their tent to sleep in and got us into the rodeo free the next day. Before long Irene fell for one of them and that split us up. She went on to the next rodeo and I started back home alone.

“It took me a few more days to make it back. My mom and dad welcomed me home and my dad never said another word about me leaving. I had traveled over three thousand miles, experienced a few bad incidents and many acts of kindness. I had seen hundreds of people, even whole families, bumming rides to try to find work during those hard times. And I had proved to my dad that I would not be back for supper.”

She continues to live a life of adventure. She has run day care centers, worked as a grocery wholesaler and in a children’s hospital, and served as a missionary in Trinidad. Once she rode a steam engine from Anchorage, Alaska, to Whittier, California. At the age of seventy-five she climbed a mountain and drove 4,212 miles in her van. “My whole life has been interesting,” she says.

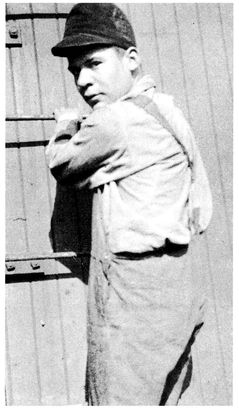

A teenage hobo climbs aboard another freight car after four years on the road.

HUMAN FREIGHT

“Men and boys swarm on every freight in such numbers that the railroad police would be helpless to keep them off … From September 1, 1931, to April 30, 1932, the Southern Pacific Railroad, with 9,130 miles of track, recorded 416,915 trespassers ejected.”

—Monthly Labor Review, 1933