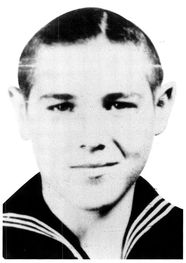

Calvin Graham in his navy uniform at age twelve

“I felt like I wanted to take on the whole Japanese fleet.”

Houston, Texas, and the Solomon Islands, 1942

On December 7, 1941, Japanese warplanes dropped bombs on U.S. ships in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing 2,403 Americans and destroying much of the U.S. Pacific Fleet of warships. The next day President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, and the United States entered World War II. Calvin Graham of Houston, Texas, was one of many thousands who enlisted in the U.S. Navy. The unusual thing about him was that he was only twelve years old. Military historians call him the youngest U.S. soldier of the twentieth century.

The U.S. Navy looked good to Calvin Graham in the spring of 1942. His life was hard. His father had died five years before, when he was seven and his brother, Frank, ten. Their mother married a man who drank heavily and forced the boys out of the house. On their own, the boys shined shoes after school, earning just enough to rent a single room in a shabby hotel. Their only furnishings were a bed, a mirror, a washstand, and a water pitcher.

Until America declared war against Japan, Calvin couldn’t even imagine a future for himself. He was in sixth grade but rapidly slipping behind his classmates. But then, at the age of fourteen, Frank forged some papers and faked his way into the navy, even though the law said you had to be seventeen to enlist. After Frank left, Calvin drifted from one flophouse to another, but at last he had a plan. If Frank could enlist, so could he. Calvin decided to wait until the end of the school year to make his move. That way, if his plan didn’t work, he could always go on to seventh grade. Until then, he would try to eat more and get stronger, since he had heard you had to be at least five feet two and 125 pounds for the navy to take you. He found a razor and started shaving to try to get a beard to grow.

In August of 1942, Calvin went to the recruiting station with his friend Cleon Jones, also underage. The recruiting officer wasn’t fooled when he looked at Calvin, but he needed sailors, since Japan still controlled much of the Pacific Ocean. “The man told me not to tell him my age,” Calvin said, “just to sign my mother’s name and tell him I was seventeen.”

He took a train to San Diego for boot camp, where a dentist noticed that Calvin’s twelve-year molars weren’t in yet. He ordered Calvin to take his file to the medical officer

to be discharged from the navy. Instead, Calvin waited until the dentist’s back was turned and placed his file in a stack with all the others. Five weeks later he was aboard the battleship South Dakota, headed for the Solomon Islands in the Pacific, which were controlled by Japanese forces. Soon the crew was trying to survive an all-out assault in the battle of Santa Cruz. Calvin was assigned to a gun crew that shot down seven Japanese planes.

When the battle ended, Calvin and his crewmates formed a line to be congratulated by Lieutenant Sargent Shriver. Shriver stopped when he got to Calvin. “He asked how old I was. I told him ‘Thirteen in April, sir.’” Shriver sent him to the captain, who told Calvin that he would have to go home at once. Calvin insisted he had only been kidding, that he was really seventeen. “[The captain told me] it wasn’t anything to be ashamed of,” Calvin said. “He had already sent three other [underage] boys home that same day.” Calvin desperately wanted to stay. He had a home now, food, friends, and a job. He stuck to his story and the captain couldn’t prove him wrong. He stayed.

In November, they fought in the battle of Guadalcanal, one of the bloodiest episodes of World War II. The South Dakota was hit again and again by enemy fire. One explosion threw Calvin down three decks of stairs. Another shell whistled in and knocked out the ship’s electrical power. The South Dakota drifted unseen in the dark until a nearby U.S. ship trained a spotlight on it. That made the ship a sudden target: Shell after shell boomed onto Calvin’s part of the boat. The room quickly filled up waist-high with reddened seawater. Dead and wounded men were all around. Screams and exploding shells and planes made hearing nearly impossible. Calvin’s partner went out for more supplies and never returned. Calvin was hit by a shell fragment, sending a bolt of pain through his head and crushing a part of his mouth. All night long he did what he could to keep his mates alive. Often all he could do was take belts off the dead to tie tourniquets for the living.

After the battle, they sailed back to Brooklyn, New York, for repairs. Calvin was awarded the Purple Heart, the Bronze Star, and several other medals for his bravery, but the ship’s captain was still troubled by how young he looked. He ordered Calvin to go home to Texas to get a letter of consent from his mother allowing him to stay in the navy. When Calvin got back with the letter, the captain had been reassigned. The new officer in charge ordered Calvin back to Houston to turn himself in to naval authorities there. “They’re the ones who signed you up,” he said sternly. “Let them straighten this out.”

A GRADE SCHOOL IN 1943

Students throughout America did everything they could to help the war effort. The yearbook of North School, serving grades 1 through 8 in Portland, Maine, lists the following student activities in 1943:

• Raised $5,315 to buy war stamps and bonds.

• Made bookmarks for injured soldiers.

• Collected flower vases to send to a Veterans’ Hospital.

• Pooled pennies to buy yarn.

• Collected 10,017 tin cans to be used by the military.

• Collected 28 pounds’ worth of keys to be turned into bullets.

• Formed a first aid class in case of attack.

• Sold 13,350 half-pints of milk to raise money for war bonds.

• Room 103 alone collected 100 pounds of tin foil, 200 keys, and 100 tin tubes.

Lessons were often about war. Children in Room 209 learned games from a book titled Fun in a Fallout Shelter. Eighth grader John Romano wrote his spring essay about the importance of chewing gum. “Gum is good for aviators when they go into a power dive,” he wrote. “So do not argue with your grocer if he has no gum. The men in the service need it more than you do.”

During the war years, students throughout America—like these from Butte, Montana—collected mountains of scrap metal, which were quickly transformed into planes, tanks, and ships.

Then Calvin’s nightmares really began. He hitchhiked home and reported. But the navy officials got his story backward. They thought he was seventeen and trying to get out of the navy by pretending he was twelve, not the other way around. He was arrested as a deserter and placed in a naval prison in Corpus Christi, Texas. His medals were taken away from him.

He stayed behind bars for three months. No one knew where he was. Finally his sister found him and got a newspaper reporter to write about him. The navy released him but refused to grant him an honorable discharge or veterans’ benefits. Two days after his thirteenth birthday, Calvin Graham, the battle-hardened war veteran, rejoined his classmates in seventh grade.

He enlisted in the marines when he finally turned seventeen. While on duty he fell from a pier and broke his back and leg, causing him to spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. The government paid him for that injury but still refused to return his medals or to pay him for the injuries he suffered as a boy on the South Dakota. He kept writing to the navy and to his congressional representatives, asking for help. He won his pay and all his medals back except the Purple Heart, awarded for being injured in battle. That was the one that meant the most to him. In 1988, a TV movie was made about him. Calvin dedicated it to all the boys who faked their age and fought in World War II. “They helped win that war,” he said. “The Americans were losing the war … we thought that if we got in and did our part, we could turn that thing around. And we did.” In 1994—two years after his death—the navy finally gave Calvin’s widow his Purple Heart.