“It really was Stan Musial … This was not junior high.”—Joe Nuxhall

A RARE OPPORTUNITY

During World War II, major league teams signed players who were older, younger, and often less skilled than usual, as long as they were exempt from military service. Some played with injuries, and more than a few retired players were offered a second chance. Team owners stubbornly refused to let African Americans play until 1947, but signed up plenty of light-skinned players from Puerto Rico, Mexico, and Cuba.

Cincinnati, Ohio, and Kenosha, Wisconsin, 1944

World War II touched everything—even baseball. When shiploads of major league players went off to war, President Franklin Roosevelt thought about stopping professional baseball until the war ended. But then he decided the game meant too much to too many people to take it away. The games went on, and major league baseball scouts looked in unusual places for players. One Saturday afternoon in 1944, a fifteen-year-old junior high school student named Joe Nuxhall found himself on the pitcher’s mound against baseball’s toughest lineup, the St. Louis Cardinals.

“It was the summer between eighth and ninth grade when they found me. My dad and I were playing in the same Sunday league in Hamilton, Ohio, but we were on different teams. One Sunday some scouts came up from Cincinnati to watch my dad play, but our game got started before his so they watched me pitch. I was only fourteen, but I was already

6’3” and 190 pounds. I didn’t have a curveball but I could really throw hard. ‘Straight ahead and let ’er fly,’ that was my motto.

“The scouts introduced themselves to me after the game and said they wanted to sign me right up. I wouldn’t do it, because I wanted to play ninth grade basketball. So I waited until right after basketball season, and in February of 1944 I signed a contract with the Cincinnati Reds. I got a five hundred dollar bonus and $175 a month. I thought I was a millionaire. The deal was that whenever the Reds were in Cincinnati and I didn’t have school I’d go down to Cincinnati and put on a uniform and sit on the Reds’ bench.

“The players were really nice to me. The first day I walked into the clubhouse, an outfielder named Eric Tipton looked up at me and asked me how old I was. I said ‘fifteen.’ He said, ‘Son, you’re big enough to kill a bear with a switch.’ When the games started I’d sit in the dugout with them, and we’d talk about what was going on, but I never even dreamed of getting to play.

“Then this one Saturday afternoon we were playing the St. Louis Cardinals and they were beating us 13—0. The ninth inning came, and I was sitting there thinking, ‘Boy, these guys can hit’ when all of a sudden our manager, Mr. McKechnie, walked down to my end of the bench and told me I was going in. I was scared to death. The Cardinals were the world champions that year. They had the hardest-hitting lineup in baseball.

“When I walked out there I was so nervous I don’t even remember what my catcher said to me. The first batter grounded out, I walked the second and the third popped up. Not bad, I was thinking, and then Stan Musial came up. I just stood there staring at him. It really was Stan Musial, the most feared hitter in the league. There was that famous red number six. This was not junior high. I looked at him for a while until I had to throw the ball. Then I did, as hard as I could. He cracked it even harder to right field for a single. If he had hit it higher it would have been a homer. After that I never got anyone else out. I walked five and gave up two hits and threw a wild pitch. They scored five runs. My earned-run average was sixty-something when they took me out.

“None of my friends or family were in the crowd that day because no one expected that I would ever get into a game. But when I got home everyone was excited. My mom had heard it on the radio. All the kids in the neighborhood wanted to know how it felt to pitch to Musial. They were happy for me. We didn’t know for a while that I had become the youngest person ever to play in a major league baseball game.”

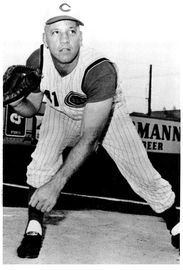

Joe Nuxhall, a major leaguer at age fifteen

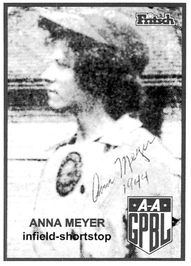

Anna Meyer’s first baseball card

That same year, the war gave another fifteen-year-old a chance to play professional baseball. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was started in 1943 by Philip K. Wrigley, a millionaire chewing-gum-company owner who also owned the Chicago Cubs. Wrigley believed that with so many major league stars away, Americans fans would pay to see good female players. He was right. Wrigley sent scouts out around the United States and Canada, holding tryouts in small towns and cities, signing the best players. The youngest player to sign a contract was fifteen-year-old Anna “Pee Wee” Meyer, who played with the Kenosha Comets and Minneapolis Millerettes in 1944.

“I grew up in an Indiana town with five baseball-playing brothers who threw grounders at me in the barn from the time I was two. After a while they were smashing them at me—in my family, it was run, catch it or get killed. By the time I reached my teens, I was playing with them on a church league team, and doing very well.

ALL-AMERICAN GIRLS PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL LEAGUE

At first their game was more like softball than baseball. Women pitched underhanded and played with a larger ball on a smaller field than men in the major leagues. The rules quickly changed when officials and fans saw how well they could play. The league drew many fans even after major leaguers came back from war. Attendance dropped off in 1949 when officials pulled money out of the league and gave control of the teams to local investors. The league disbanded in 1953.

“When my dad heard that there was going to be a pro league for women, he wrote a letter to league officials, recommending this anonymous girl he had seen with great talent. He got a letter back telling him to send her to an upcoming tryout in Peru, Illinois, as long as she wasn’t working in an important war-related job.

“Everyone around town said, ‘She’ll never make it,’ and my mom thought I was too young to leave home. On the day Dad and I went to the train station she said, ‘I hope you don’t make it.’ She was crying when we left. I was so determined, though. All the way up on the train I pounded a ball in my glove, not really listening to anyone, just thinking about what I had to do. When we arrived, there were so many women trying out that they had to use six diamonds. They made us all wear little dresses, which was terrible when you had to slide because your legs were unprotected.

“It was a two-day tryout. The first day was a disaster. I tried out at shortstop and made a bunch of errors. I had never been away from home before and I was very nervous and just trying too hard. That night my dad and I had a talk in the hotel. He said I had done terribly and I surely wasn’t going to make it, and he wondered what I was going to say to everyone when we

got home. I just looked at him and said, ‘I’m not going back home, Dad.’ The second day I just burned up the diamond. I fielded everything and threw like a rocket. By the end photographers were taking my picture, and I knew I had made it. After the workout they offered me a contract, for forty dollars a week, plus expenses. That was five dollars more than my dad made.

“I wept a bit when I sent my dad off home, but not for long. I was too busy. We finished spring training and then went off to Kenosha, Wisconsin. Two great players, Pepper Pare and Faye Dancer, took me under their wings. Pepper was a catcher, and we worked endlessly on throws to second base. ‘Look,’ she kept saying. ‘Prepare yourself for a terrible throw and then you’ll be ready for anything. If it’s a good throw, that’s gravy.’ We studied how to position ourselves for certain batters, footwork, anticipation. I learned so much. I lived with a roommate in a family’s home, and we traveled from city to city in trains filled with soldiers. The women smoked, drank, and swore. I didn’t but I loved them anyway and I loved being around all the soldiers. I learned a lot about life. Midway through the season I got traded to Minneapolis. There were even bigger crowds and I signed even more autographs.

“We made the playoffs and I didn’t get home until nearly October. My teachers let me make up lost work at night, and I got quite a reception. I was named my town’s ‘Athlete of the Year’ and rode through town in a float. I had to wear a dress but it wasn’t so bad. There I was, a fifteen-year-old girl making my living as a professional athlete. What a time it was! I loved every minute of it.”

Joe spent seven more years in the minor leagues and finally worked his way back up to the Cincinnati Reds, where he became a fine major league pitcher. He pitched fifteen years for the Reds, with a record of 135 wins and 117 losses. At this writing he is the radio voice of the Cincinnati Reds. Joe is married and has a son.

Anna played five more years and then left to go to college and was soon married. To help pay expenses she took a job in a leather factory and was invited to play on the company’s softball team. She had told no one about her baseball career. Early in the first game she fielded a grounder at third and fired the ball to home plate. The catcher went down in a heap. “They had to bring in the rescue squad,” Anna recalls. She is the mother of two boys, and, like all former players in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, a proud member of the Baseball Hall of Fame.