“A talk show host offered to lend a gun to anyone who would shoot my dad.”

Des Moines, Iowa, 1965-1968

The Vietnam War divided Americans in the 1960s and early 1970s. First the U.S. government sent military advisers to help one side of a civil war in Vietnam. Troops and high-tech weapons followed. It was like wading in quicksand: Every new step made it harder to get out and caused more and more people in the United States to oppose the war. By 1968, there were 520,000 American soldiers in Southeast Asia and huge protests at home. John Tinker was part of a large Iowa family of war protesters. In 1965, John, fifteen, his thirteen-year-old sister, Mary Beth, and their friend, Chris Eckhardt, fifteen, wore armbands to school to protest the war. When they were expelled, they sued their school system, and the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The decision in Tinker v. Des Moines still affects the rights of students to say what they like in school.

EASIER TO GET IN THAN OUT

Lyndon Johnson became president in 1963 after John Kennedy was assassinated. Although Kennedy had already begun to send U.S. troops to Vietnam, Johnson sent more and more. The idea was to stop the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia. But protesters blamed the war on him. A favorite chant went “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

But tape recordings of phone conversations released after Johnson’s death show that he was tormented by what he was doing and by the deaths of American soldiers. He called the war “the biggest … mess that I ever saw” but feared that Congress would impeach him if he pulled troops out of Vietnam. “I don’t think it’s worth fighting for,” he told his national security adviser in 1964. “But I don’t think we can get out.”

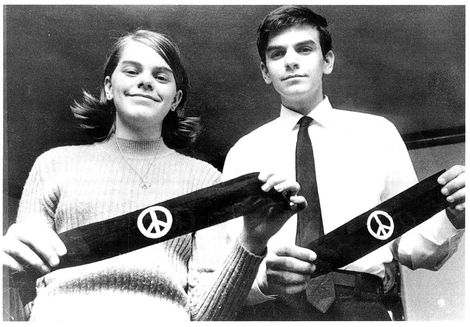

Mary Beth and John Tinker display the antiwar armbands that caused them to be dismissed from their schools and propelled their lawsuit into the U.S. Supreme Court.

HIPPIES

In July of 1967, a fourteen-year-old middle school student named Colin Pringle read a Time magazine article titled “Hippies: The Philosophy of a Subculture.” It was about a large group of people living communally in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. They shared food, music, living space, and a desire to experiment with new ways of living. He knew it was for him, and soon made his way to San Francisco to see for himself. People he met stayed up all night talking about ideas. “Although I dug the long hair, beards and clothes,” he recalls, “it was their values that attracted me the most.”

Colin was one of many thousands in the 1960s and early 1970s who “dropped out” of established society and sought to create alternatives to it. Though nearly all hippies opposed the Vietnam War, not all were politically active. “I dropped out because of the dress code at my school,” Colin recalls, “and because I had no desire to grow up to climb the corporate ladder.”

“Starting in 1961, when I was eleven, the Vietnam War became a big part of our family’s dinner discussions. I read a lot about it and I heard speakers talk about it and I made up my mind. I opposed our involvement in Vietnam because it was a war. I didn’t believe that there were good wars and bad wars. I was brought up to value human life and to see war as a defeat. It meant that better ways hadn’t worked. Besides, we weren’t defending ourselves. We were dropping bombs onto thatched roofs.

“I argued about the war with anyone who wanted to argue with me. Somebody at my school sizing me up might have said, ‘He’s wrong, but he’s a good debater.’ I had a handful of good friends but I wasn’t popular. The popular kids couldn’t risk their popularity by taking unpopular positions. I could.

“One weekend when I was a sophomore, I went with a church group to a protest march against the war in Washington, D.C. On the way back we decided to wear black armbands to school until Christmas as a way of supporting Senator Robert Kennedy’s call for a Christmas truce. About a dozen students in the Des Moines school system did it, but I was the only one from North High. My sister Mary Beth, my eleven-year-old sister, Hope, and my eight-year-old brother, Paul, also decided to do it. So one night we bought black cloth and made armbands.

“Early on the morning of the first day we were going to protest, I was delivering newspapers on my paper route and noticed a story about it. I was amazed because we hadn’t even started yet. It said that all the principals had gotten together and banned the wearing of armbands in the Des Moines school system. The story changed things for me: Now we weren’t just protesting, we were committing an act of disobedience. These were things you talked out very carefully before you did them. I raced home and tried to call the others. But Chris Eckhardt [a friend who had been on the trip to Washington] and Mary Beth had already left for their schools with their armbands on. I didn’t wear mine that first day because I still wanted to talk it over first.

“That night we met at Chris’s house. Chris said he had gone straight to the office and presented himself. When he had refused to take off the armband, the vice-principal of his school had said, ‘Do you want a busted nose?’ When they called his mother, she said, ‘I support what he’s doing.’ So they sent him home and told him not to come back with the armband on. They had told Mary Beth to take off her armband too, and she did, but they kicked her out anyway. We called the school board president for a meeting but he refused, saying it wasn’t worth his time. After that, I felt real clear about what I was going to do the next day.

“I was really nervous before school the next morning. There was a story in the paper about Chris and Mary Beth being kicked out. They stayed home, but the other students dropped out of the armband protest, mainly because their parents didn’t want to risk losing their jobs. Our parents were terrific—they supported us all the way.

“I put on a dark suit coat and a tie to show respect for the school, stuffed the armband in my coat pocket and walked out the door. I kept thinking, ‘Will this day change my whole life?’ I meant to put the armband on as I was walking, but I couldn’t make myself do it. After home room I went into the bathroom and tried to pin it on, but my hands were shaking so hard I couldn’t. I was fumbling with it when a friend of mine came in and helped me. Then I walked around with it on, trying to look normal, but I had to have looked pretty strange especially since I had never worn a suit coat to school before. But for some reason nobody said a thing about it. Finally I realized no one could see it against my dark coat. So I took it off and put the band on over my white shirt. Then it stood out real well.

“At lunch, as I sat with my friends, some students walked by and called me a ‘Commie.’ It made me feel nervous, because I wasn’t used to being the center of attention. And I kept wondering … ‘How come I haven’t been kicked out of school yet?’

“Then an office secretary spotted the armband and reported me. I got called in to see the principal, Mr. Wetter. He said I was putting a black mark on my record, and that this could make it hard for me to get into college. We debated. He said wars are necessary sometimes. Finally I told him, look, I knew what I was doing and that if he had to kick me out of school then I would leave. He called my parents and my father came for me.

“Chris, Mary Beth and I stayed out for four days, until Christmas break. Paul and Hope kept going to school with their armbands on, because the grade school principals hadn’t banned them. During the break there was a lot of publicity about our stand. Many people in Des Moines were angry at our family. On Christmas Eve, Mary Beth answered a phone call from someone who threatened to blow up our house. Someone flung red paint on our driveway. A radio talk show host offered to lend a gun to anyone who would shoot my dad. At night I would lie in my bed wondering, ‘If someone throws a grenade through the window, what will I do? Dive into the closet? Put the mattress over my head?’

“Over the holiday break we had a big community meeting about what to do next. Lawyers from the Iowa Civil Liberties Union said we might be able to sue the school on the grounds that we had been denied our right to free speech under the First Amendment to the Constitution. We decided we’d go back to school without the armbands so we could keep studying, and we would sue the Des Moines school system. I wore black for the rest of the year.

OLD ENOUGH TO FIGHT AND VOTE

The Vietnam War produced many changes in American life. One was the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the Constitution, passed in 1971, which lowered the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen. It reflected the widespread opinion that young men who were old enough to be drafted into the armed forces should be able to vote for or against officials who could lead their nation into war.

“People called me ‘Pinko’ and ‘Commie’ all year long. A physics teacher told me he lowered my grade because of what he called ‘my attitude.’ A history teacher told me he raised my grade to make up for it. An English teacher said in class that maybe these protesters ought to be hung up by their thumbs. Some teachers gave me a chance to talk to their classes, to give my side of the Vietnam War. I welcomed these chances, but I was feeling weird at school.”

In April 1966, their lawsuit against the Des Moines school system was heard. John, Mary Beth, and Chris testified in the federal district court in Des Moines. Their lawyers argued that the rule against armbands cut off their right to free speech. They also contended that the rule unfairly banned one form of expression—armbands—but allowed other expressions like wearing political campaign buttons or religious ornaments. The school system’s lawyers countered that the school had the responsibility to maintain the health and safety of the students. They said the rule against the armbands was necessary to keep discipline, especially since a former student in one of the Des Moines high schools had been killed in Vietnam.

Throughout America young antiwar demonstrators—like these in Chicago—found ways to protest.

“The courtroom was filled with our supporters. Mary Beth, Chris and I were cross-examined by lawyers for both sides. The lawyer for the school board tried to prove that our parents had made us wear the armbands. We lost. The judge ruled that the schools could ban the armbands if they wanted to.

“We appealed the decision in the summer of ‘66, in St. Louis. It ended in a tie, 4—4, which meant that the lower court’s ruling still stood. So we appealed for a hearing with the U.S. Supreme Court. I was driving around town when I heard on the car radio that the Supreme Court had decided to take the case. It didn’t get argued until the fall of 1968, when I was a freshman at the University of Iowa. It came up so suddenly that I couldn’t get to Washington, D.C., in time. The hearing was all over by the time my family picked me up at the airport.

“In the spring of 1969 it was announced that we won, by a 7—2 majority. The decision still affects students. The armband case

made it clear that school officials can’t just clamp down on kids for expressing their thoughts. They can tell you not to shout or fight or clap during class, but they can’t keep a kid from expressing a thought based on the content of what they’re saying. The Supreme Court basically just said, ‘No, that’s not the kind of society we have here.’”

After a brief time in college he dropped out of school and decided to educate himself through reading and traveling. At this writing he lives in an old schoolhouse that he bought and fixed up, and he makes his living as a computer expert.

WHAT THE SUPREME COURT SAID

“School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are persons under our Constitution. In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate. They may not be confined to the expression of those sentiments that are officially approved … Children do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse door.”

—U.S. Supreme Court justice Abe Fortas, writing in the Tinker v. Des Moines case