“Now I see you can fill this gym.”—Warsaw High athletic director Ike Tallman

Warsaw, Indiana, 1976

The 1972 Educational Amendments, passed by Congress, made new rules for schools that receive federal tax money. One section, known as Title IX, requires these schools to provide equal “access and opportunities” for women and girls in education. That meant sports, too, and it was a major change. Most schools had sports programs for boys but very little to offer girls. Basketball-crazy Indiana was typical: There was a huge high school boys’ basketball tournament, but there was no post-season tournament at all for girls. Judi Warren was an exceptional basketball player who grew up in a small Indiana town during those years of change.

“ENTHUSIASM WITHOUT HYSTERIA”

That was the goal of Miss Senda Berenson, who introduced basketball to America’s women’s colleges in 1893. She was the physical education director at Smith College and learned the game from its inventor, James Naismith. She didn’t like keeping score. “We should encourage the instinct to play,” she wrote, “not necessarily competition.”

High school girls first played basketball in Indiana five years later. They wore bloomers, middy blouses, and scratchy, high cotton stockings. Girls smiled at one another as they faced off for the center jump. They stood tall with one hand raised above their heads, looking like they were about to pair off for a ballroom dance. The floor was shortened and some girls were not allowed to cross a certain line or shoot the ball. Hard competition was discouraged for many years. “Better than winning honor in basketball is deserving credit for ladylike conduct,” explained the Hobart, Indiana, Gazette in 1915.

Judi Warren, Cindy Ross, Lisa Vandermark, and Cathy Folk played basketball together all through seventh and eighth grade. “It got so my teammates were closer to me than my own family,” Judi remembers. “We really understood each other. Any of us would do anything in the world to keep one of the others from going down.”

TITLE IX’s EFFECT

In 1971, the year before Title IX was enacted, only 7.5 percent of all high school athletes in the United States were girls. By 1996, it was 39 percent. Powerful, well-funded college programs developed, spawning two women’s professional basketball leagues. When the 1999 U.S. Women’s Soccer Team won the Women’s World Cup, they played before a TV audience of forty million people and a live crowd of nearly eighty thousand. A few months later, more than seven hundred girls’ soccer teams entered a Washington, D.C.—area soccer tournament, far more than expected. College coaches begged tournament sponsors to keep the numbers low, so they could have a better chance to scout players for scholarships. One teenage midfielder told a reporter, “You can feel the future just around the corner. I see a professional career as a distinct possibility.”

When they entered high school they became the core of the Warsaw High girls’ team, but very few knew about them. At Warsaw, basketball meant boys’ basketball. While the boys played on Friday and Saturday nights before thousands of fans, the girls played their midweek games after school in front of a few loyal friends and family members. Socially, boy players were admired as heroes while girl athletes were scorned as “jocks.” “We weren’t the cheerleaders and high society girls all the other girls looked up to,” Judi recalls. “And it wasn’t cool to date a jock … At times it was discouraging but usually we just went out and had a good time.”

The men who ran the sports programs at Warsaw seemed to feel the girls should be grateful they even had a team, since ticket and food sales at the boys’ basketball games helped pay for the other sports programs. Judi, Cindy, Lisa, and Cathy saw it differently: Warsaw High was their school, too. Why couldn’t they have uniforms? Why should they have to practice in a grade school at 7 P.M., while the boys practiced in the Warsaw gym right after school? The late practices meant that Judi, who lived in the country, rarely got home before ten. Most irritating of all, the Warsaw girls did better than the boys’ team. Going into their senior year they had lost only four games since ninth grade.

The girls blamed their problems on the varsity boys’ basketball coach. Ike Tallman was a tall, imposing man who wore dark, formal suits to school. He had once coached a team to the Indiana boys’ championship, which only added to his heroic and intimidating stature. Still, the girls realized they would have to confront him if anything was going to change. One evening after school, their hearts pounding, Judi, Cindy, and Lisa stepped into Warsaw High’s athletic office and placed a list of demands on Mr. Tallman’s desk.

He studied the list for a moment—uniforms, laundry service, buses to games, cheerleaders, and equal access to the high school gym right after school—and then looked up. He didn’t seem angry, just busy. He told them that when they could fill up the Warsaw gym, as the boys did, then they could share it. He said that he would have his secretary print them some tickets and they should see if they could sell them. Then he turned back to what he was doing. Lisa, who had written the list, was furious but somehow held her tongue. Cindy burst into tears. When the tickets arrived, the girls tried to sell them at their churches and

among their friends, but attendance didn’t increase much. It looked like things would never change.

But important changes were happening in Indiana. In 1972, the year Title IX was enacted, a South Bend girl had sued her school for the right to play on the boys’ golf team, since the school had no team for girls. She won. Another Indiana schoolgirl won the right to play on the boys’ baseball team. New sports programs for girls were springing up at schools throughout the state. Best of all, at the beginning of Judi’s senior year, the Warsaw girls learned that the first Indiana girls’ state basketball tournament would be held that March. It would mimic the boys’ tournament, with all of Indiana’s 359 high school girls’ teams competing, no matter how big or small the school was. One loss and you were out. The event would take a whole month, with four separate weekend rounds—sectionals, regionals, semi-state, and the championship round in Indianapolis.

Though the odds of winning the tournament were slim, the Warsaw girls thought they had a chance. They had been playing together so long that they were like a single organism. No team had come within twelve points of beating them all season. They had almost forgotten what it felt like to lose.

The usual scattering of relatives and friends watched them win the sectional final against Plymouth High, 52—38. As proud champions, once again they asked Mr. Tallman for better uniforms and cheerleaders. He agreed to let the junior varsity cheerleaders accompany them to the next weekend’s regional tournament in Goshen. When they won, becoming one of only sixteen teams left in the tournament, their schoolmates seemed to notice them for the first time. Posters covered the halls. People they barely knew stopped at their lockers to wish them luck. Fifteen hundred Warsaw fans traveled to Fort Wayne to watch them play in the semi-state round. And when they won again, qualifying for the Final Four in Indianapolis, there was high-voltage excitement in Warsaw.

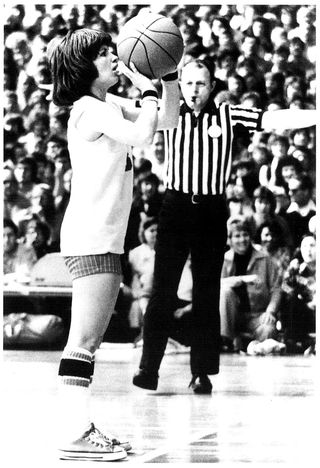

Judi Warren shoots a free throw.

A few afternoons later, the school held a send-off pep rally for them. Judi, Cindy, Lisa, Cathy, and their teammates walked nervously into the gym and sat down on a row of folding chairs that had been placed in the middle of the basketball court. They stared self-consciously at bleachers filled with their schoolmates.

The pioneering 1976 Warsaw Tigers, Indiana’s first high school girls’ champions

After a few speeches and cheers, Mr. Tallman walked slowly across the polished floor and stood before the microphone. The gym fell silent. Looking directly at Lisa, he began. “Some of you have been after me to share this gym,” he said, “and I said, ‘No, not until you can fill it.’ Well, I owe you girls an apology.” He swept his hand in a slow arc around the room. “Because now I see you can fill this gym.”

“After that,” Cindy Ross recalls, “we got a whole lot of respect for him. It took a lot for the head coach of the Warsaw boys to say he was sorry to a team of girls in front of the whole school.”

Warsaw faced East Chicago Roosevelt in the first game of the championship round. Roosevelt was a strong, big-city team led by freshman La Taunya Pollard, who would later be named the outstanding woman collegiate player in the United States. Roosevelt jumped off to a quick eight-point lead, but Judi stole the ball repeatedly in the second quarter, threading her way through defenses and hooking passes over her head for easy baskets. Warsaw turned the game around and won by a big margin.

A few hours later they played Bloomfield High for the state championship. There were more than nine thousand people in the stands and a big prime-time TV audience. It is still remembered as the game that put girls’ basketball on the map in Indiana. The contest was close until the final minute, when Judi once again took over, slashing through the defense to score, or pass for assists. Warsaw won 57—52.

When the last strands of the net had been snipped down, the girls climbed into a Winnebago van and headed home for some sleep. “I was hoping my parents would still be up to drive me home,” Judi remembers. The van pulled into the school lot at 3 A.M. When

Judi drew her curtain back, she was looking at a police officer. When they opened the door, he said, “Better run, I don’t think we can hold the crowd back any longer.” Almost no one in Warsaw had gone to bed that night. Once again the gym at Warsaw was filled, this time well after midnight, and this time to celebrate Indiana’s first girls’ high school champions.

She won a basketball scholarship to Franklin College and became a star player. At this writing, she is the head girls’ basketball coach at Carmel High School, outside Indianapolis. Her players wear first-class uniforms. They share practice time on the main court with the boys and coordinate schedules so that both girls and boys get a chance to play on Friday and Saturday nights.

In 1996, Judi coached her team to the final game of the Indiana championship. Almost fifteen thousand fans attended the game, including almost all of Judi’s old Warsaw teammates. Carmel lost by four points.