“It started with seven kids, right around my kitchen table.”

Maryville, Arizona, 1990s

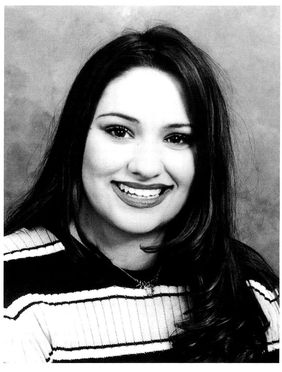

In 1988, nine-year-old Kory Johnson’s older sister Amy died from heart problems after a lifetime of serious illness. Amy’s problems were probably caused by well water, contaminated by industrial cleaners, that her mother had drunk while pregnant. Months later, Kory started Children for a Safe Environment, and she has been organizing to keep polluters out of poor neighborhoods ever since. Her success has made her a speaker at youth conferences throughout the country. In 1998, at the age of nineteen, Kory Johnson won the $100,000 Goldman Environmental Prize, recognizing a decade of work on behalf of the environment.

“I grew up watching Amy. Often I was in her hospital room. When she could come home, she was always hooked up to oxygen. Night after night I heard my mom go in her room to make sure the oxygen was working. Even though we had separate bedrooms, we often ended up sleeping together. We did everything together.

“She died on Valentine’s Day, 1988. Not long afterwards, the Centers for Disease Control named our neighborhood a ‘cancer cluster,’ meaning that there was an unusual concentration of people with cancer there. It fit, too. Many children in our neighborhood

had cancer and leukemia. My grandmother had it, and my mother, [and] many of her high school classmates.

“I couldn’t accept Amy’s death; I would go in her room and smell her clothes. My mom sent me to a bereavement group for kids who had lost siblings. A lot of them were from our neighborhood. We kids started talking. We decided we liked meeting every month, but we didn’t like crying. We decided to start a group to find out why so many kids were dying. We called ourselves Children for a Safe Environment [CSE]. It started with seven kids, right around my kitchen table.

“Right when our group started, a company called ENSCO—Environmental Systems Company—applied for permits to put three hazardous waste incinerators into our community. They wanted to dump all the toxic wastes produced in the whole state there, and bring in more from out of state. Ours is just the kind of community dirty industry normally targets: poor people, minorities—I’m Mexican-American on my mother’s side and Oglala-Sioux on my father’s—not well educated [and] needing jobs. They promised everyone jobs and took the graduating class of a nearby school to Disneyland. A whole lot of people got excited. But we weren’t excited. If this happened, trucks full of contaminated waste would be driving by all day long right in front of the grade school.”

For the next two and a half years, Kory led CSE through a series of hearings and campaigns to oppose the incinerators. They wrote letters to public officials, testified at public hearings, and organized protests, demonstrations, and art projects, sometimes on their own and sometimes working with the adult-led environmental group Greenpeace Action.

“Right away we could see we had to learn about hazardous wastes. Whenever we’d go to a public meeting, reporters would ask us, ‘Are you really concerned, or are your parents making you do this?’ We made phone calls all over the U.S. and ordered educational materials. We taught ourselves. We’d make lemonade stands to raise money to send someone—often me—to conferences to get information. I learned not to waste my time going to information meetings organized by industry, but that it was important to attend public hearings where you can find out what the issue is, who controls it and what is being proposed. I learned to follow the dollars, and how to find out whether my political representatives had accepted campaign money from the industries proposing the project.

LOSS OF SPECIES

In 1616, Great Britain passed a law against “the spoyle and havoc of the Cahows and other birds” in its colony of Bermuda. Cahows were sea birds that nested in underground tunnels, and rats from European ships were gobbling their eggs. It was the first law aimed at protecting an endangered species in the New World. It didn’t work. All the cahows disappeared by 1629.

Throughout colonial times and U.S. history, nonhuman species continued to lose ground. In 1962, scientist and author Rachel Carson shocked readers by warning of a “Silent Spring,” in which songbirds would be wiped out by environmental poisons. Her warning led to the ban of the pesticide DDT in 1970, which helped some species recover. But at this writing, 1,251 species of plants and animals—including the manatee pictured here—were officially listed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as endangered or threatened.

“I learned to write good letters, to stage skits, to talk in sound bites at public meetings. I always mentioned my sister when I spoke, and if it made them cry, fine, because I don’t want anyone to lose someone like Amy. Most of all I learned to organize, to use everybody I could. Some kids would say, ‘My mom will let me play at your house, Kory, but I can’t go to any more protests with you.’ I’d say, ‘Fine, can we make some signs together while you’re here?’ Our rule was that any action was fair, as long as we didn’t commit acts of violence or destroy property.

“We did all sorts of things. Once, we and two other groups hauled a bed onto the lawn of the state capital. We carried briefcases and got in the bed two at a time and passed money back and forth. One [person] was industry and the other was our government. We said we wouldn’t move the bed off the lawn until industry got out of bed with government. It went on for days and attracted bigger and bigger crowds. Reporters loved it—after a while they got in the bed. We made a sign-up sheet, and CSE’s membership went from 7 to 359 [from] that one event.

“We developed creative ways to do press releases. We did a protest on Halloween, and put candy in the press packs. We organized a candlelight rally one night at the state capital, with no adults allowed to participate. Kids came one by one to a microphone to express their concerns, and every news outlet around covered it. One of the girls in our group—Amanda King—noticed that ENSCO had spelled the word ‘Environmental’ wrong on their stationery. They left out the second ‘N.’ We called a reporter and they did a huge article making fun of the company and playing up the fact that a kid had discovered the spelling error.

“My mother and I were both often in the news, and not everyone liked it. One teacher told me, ‘If you keep this up, Kory, there’s not a college in the world that will accept you.’ Other teachers would sort of whisper, ‘Keep up the good work, Kory, here’s ten dollars for your organization.’ It bothered me that they felt they had to whisper.

“Finally, as a result of the protests, the State of Arizona paid ENSCO forty-four million dollars to leave. They backed out. In his speech, the Governor said that if he hadn’t taken the action, his sons wouldn’t have let him come home. It made us kids feel good.

“After that, people around the country started calling me, asking me to speak, to help them organize, to take part in their Earth Day [events]. Sometimes my mother and I would go without good food to send a package of information across the country by overnight express.

“All through my high school years I kept on organizing. I was a cheerleader, and a dance team leader, and did a lot of other school things, but I was determined that young people should have a safe place to live, no matter how rich or poor they were, or what race they were. We fought a scheme to bring forty-five freight cars of DDT-contaminated dirt from California to be dumped in our neighborhood. That time I got arrested for carrying a sign that said, ‘Save the Children.’ The police grabbed me and put me into a Jeep and took me downtown and made me go to court. My mother was frantic. It got on the news, and school officials found out and said I couldn’t be a cheerleader anymore. It was right before a big football game. The players were great—they said that if I wasn’t on the field when the game started they would put their helmets down and walk off. Soon after that, my mother got a call saying everything was all right—I could cheer after all.

“I really get tired sometimes, burned out, but I’m not going to quit. We’re talking about our future. If we kids don’t do something, it’s going to be worse. Older people tell me of all the places they could swim when they were young that are closed now, and of the birds and animals they saw that are rare now. My mom went to the same school I did. She said when she went there, there was only one kid in the school who had asthma. Now the nurse has three desk drawers filled with inhalers.

“I would advise kids to get going. Learn about issues, find out who runs your communities, propose good projects of your own. Talk from the heart. Find teachers or other adults to help. Insist on classes that teach more about the environment than the need to recycle and not litter. Get real, practical information. I get really excited when I go to youth conferences of environmentalists. There are a lot of kids willing to work.

“Some of my friends who have come and gone from CSE wonder why I’ve kept going. I watched my sister die. Ten years later, anytime there’s a truck on the freeway, I’m wondering what’s in it. And anytime I see a smokestack pouring, I’m wondering what’s in the smoke. All kids deserve a safe place to live, rich or poor. I’m in this for life.”

After considering offers from several colleges, Kory enrolled at Arizona State University, where she is majoring in psychology. She plans to become a psychologist to help children who have lost siblings.

EARTH DAY

In July 1963, Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson boarded a plane bound for San Francisco, frustrated that after six years of trying he had not been able to convince political leaders that the quality of the environment should be a major national issue. During the flight, a magazine article gave him an idea: Why not stage a nationwide teach-in on the environment? Almost as soon as the plane touched down, he wrote a description of Earth Day. He sent copies to politicians, funders, college newspapers, and one to Scholastic magazine so the idea could reach younger students. On April 22, 1970, more than ten thousand grade and high schools took part in the first Earth Day. On its twentieth anniversary, two hundred million people from 141 nations took part. Today, many of the nation’s most dedicated environmental activists are young leaders like Kory Johnson.