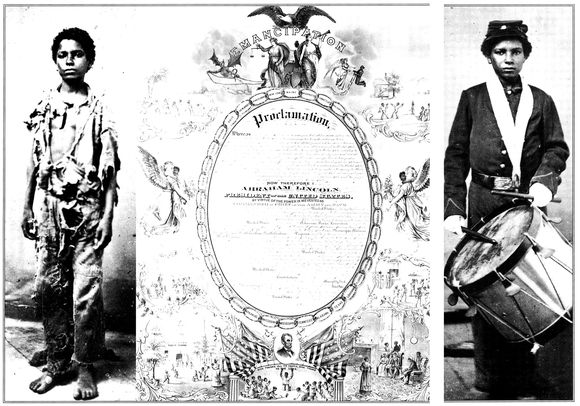

The Emancipation Proclamation helped turn slaves like the ragged boy known only as “Contraband” Jackson into a uniformed drummer for the Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Troops.

One Nation or Two? The Civil War

The long-rising tension between slave states and free states finally burst into outright rebellion in December 1860, when South Carolina simply left the United States. Within months, ten other Southern states followed. They formed their own nation, the Confederate States of America, named their own president, printed their own currency, and raised an army. The United States insisted they couldn’t get away with it: The Constitution said we were one nation, not two. But at 4:30 A.M. on April 12, 1861, Confederate cannons opened fire on Fort Sumter, a federal fort guarding Charleston, South Carolina. The Civil War had begun.

Recruiting officers soon needed soldiers so badly that as many as 20 percent of all soldiers on both sides were younger than eighteen, the official age of enlistment. Many eager boys wrote the number eighteen on a piece of paper and slipped it into their shoe, so that as they stood before a recruiter they could honestly say they were “over eighteen.” Townspeople sent them off with parades that made them feel like heroes. Boys who enlisted learned to gamble, suffer, smoke, drink, swear, steal food, kill, and bury their friends. Girls became nurses, farmers, spies, and teachers—and, sometimes, heads of families.

For four years they fought without helmets, using new, powerful weapons. At the war’s end, 600,000 soldiers, including one-third of all rebel forces, were dead. Slaves were free but faced an uncertain future in a shattered South. Most survivors who still had both legs walked home. One teenage Confederate veteran wrote: “I found my father and mother working in the garden. Neither knew me at first glance, but when I smiled and spoke to them, mother recognized me and with tears of joy clasped me to her arms.”