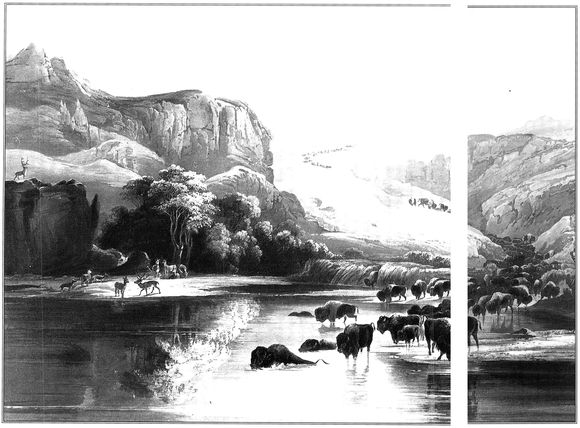

Herds of Buffalo and Elk on the Upper Missouri River. In 1833-1834, Karl Bodmer, a young Swiss artist, traveled twenty-five hundred miles along the Missouri River, painting and drawing western landscapes and native people.

Elbow Room: The West

Early in the nineteenth century, many American schoolchildren learned a song that began: “Daniel Boone was ill at ease when he saw the smoke in the forest trees. There’ll be no game in the country soon. ‘Elbow room!’ cried Daniel Boone.” It was a popular song because so many settlers dreamed of having more space. Steadily, thousands of them hiked westward over the Appalachian Mountains and paddled and poled their way down broad river valleys. They cleared fields, built cabins, and carved the wilderness into new states. Daniel Boone led his own family across the Mississippi River in 1799. At first they lived on Spanish soil that then became French territory. But in July of 1803, President Thomas Jefferson bought all of France’s land in North America for four cents an acre, instantly doubling the size of the United States. Now the United States owned all the land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Most of it was as unknown to whites as the surface of the moon.

Settlers kept on pushing until they were out of elbow room. “There is no more frontier,” declared the U.S. census of 1890, and it was true. By then, cattle trails stretched up from Mexico to the railroads like veins in a weathered hand, and steel rails cut gleaming ribbons in the prairie grass from ocean to ocean. There were three times as many people living west of the Mississippi River as there had been in the whole country just eighty years before.

For some, life changed almost totally. The great Sioux chief Sitting Bull grew up in the 1840s hunting buffalo on horseback and learning to be a warrior. By the 1880s, many of his loved ones were dead, his people were confined to reservations, his children attended white-run schools, and the buffalo were all but gone.