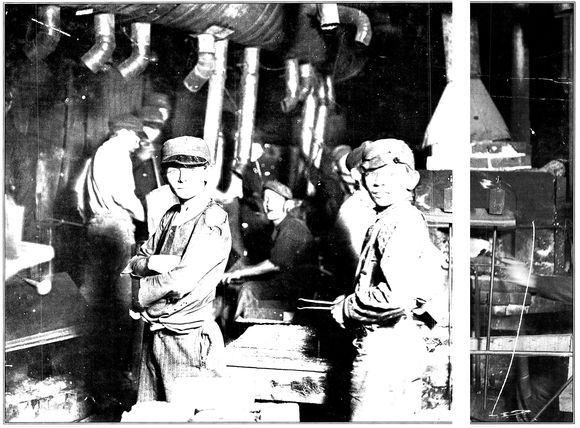

Boys working the night shift at Indiana Glassworks in 1908

Shifting Gears in a New Century

American cities sizzled with energy in the first years of the twentieth century. Overnight, dirt roads became rowdy neighborhood streets filled with farm families, immigrants, and African Americans from the South who poured into cities. In 1908, a young Brooklyn teacher described her third-grade class in a letter to her mother: “There are twenty-eight students. Six speak English, and the rest speak eight other languages, of which I know a few words of only three. We use sign language and get along as best we can.”

New inventions changed the way nearly everyone lived. Between 1875 and 1925, Americans were introduced to electric lights, movies, radios, telephones, bicycles, airplanes, subway trains, typewriters, washers, dryers, irons, refrigerators, cars, and tractors. Engineers used new ways of making steel to send buildings up into the clouds and stretch bridges across even the widest rivers. They built one steamship that was four blocks long. It was called the Titanic.

By 1880, nearly 20 percent of all workers were fifteen or younger. “The most beautiful sight we see is a child at labor,” said the founder of the Coca-Cola Company. Families came to depend on the incomes of children, who worked long hours and struggled to stay awake as increasingly powerful machines ground on. “We don’t have many accidents,” one mill owner told a government investigator. “Once in a while a hand gets mashed, or a foot, but it doesn’t amount to anything.”

The children fought back. Young millworkers, stitchers, miners, and newsboys—even golf caddies—joined and led strikes for higher pay, shorter hours, and safer conditions. It may be that young Americans never worked or played harder, or suffered more, than in the tough, raucous years of the early twentieth century.