CREATION

PORTRAYING OUR EVOLVING PLANET

When I was in college and first became enthralled with photography, I frequented the local used bookstore in search of photography books. When I had some spare cash, I added a new book to my small but treasured collection. One of the first books I discovered was The Creation, by Ernst Haas. I was fascinated by the imagery, but even more so by the innovative theme of the book itself. The process of bringing images and concept together in a meaningful way was most intriguing. Besides the great photographs, the use of Genesis from the Bible to powerfully evoke Creation made the whole package far more powerful than the parts. This book provided a moving experience that celebrated the Earth as a grand gift, and upon seeing the magic as revealed by Haas, it made me appreciate nature more fully.

Inspired by Haas’s book and others, I knew I wanted to create my own photography books someday. What I didn’t understand was the depth of imagery needed to make such a project work. It was one thing to make a few strong photographs on a subject, but it was another to accumulate a body of work that was both extensive and strong. Ideas within which a group of such photographs could resonate were still harder to come by.

Resonance is what The Creation had for me. The dictionary states that something is resonant if it has “. . . a prolonged, subtle, or stimulating effect beyond the initial impact.” This is the quality I wanted in my imagery and hoped for in my books—for the viewer to feel resonance with the magic and mystery of nature.

The subjects that have drawn my attention throughout my career are those that, when pared down by the process of composition, reveal the landscape’s essential forces. Images of these forces might show the erosion in the sandstone of a slot canyon, or geologic plate tectonics seen in the uplifted strata of the Himalayas. This trend in my work was reinforced when I started work on a book called Traces in Time for the Exploratorium. It involved illustrating these very forces with images that show the process of changes in nature. The editing process showed that I had most of the images needed for the book already in my files. The creation theme appeared repeatedly in my work, and I then realized more clearly the influence of Haas’s book.

My travels have taken me to many wonderful sights, some serene and some monumental. Probably the most awesome sight of all was on the island of Hawaii. I watched creation in action as lava turned to stone as it poured into the sea.

I photographed the lava flows at the fading light of sunset, experimenting with various exposure times. At the beginning of my session, while there was more light, I worked with faster shutter speeds at around a quarter of a second. This effect slightly blurred the motion of the waves and conveyed the action before me. The ground trembled with geologic energy. As darkness came, I used slower exposure times of several seconds. As seen in the first photograph, the long exposure times enhanced the glow of steam as it was painted orange by the lava. The dark steam clouds, blown away from the flow, were also blurred in an intriguing way by the slow shutter speed. There was just enough light left to have a sense of the landscape, and it was just dark enough to bring out the glow of hot lava.

The action of wave and lava changed constantly. Given the limited amount of good light, the motor drive allowed me to record many variations and combinations of waves cresting or pulling lava down the beach as they receded, or of the steam clouds shifting within the scene. In spite of all the frames I exposed, only one image (shown on the next page) captured a surging wave at just the right instant at just the right shutter speed. Many frames were very good, but these two images were the best, thanks to the speed of using the 35mm format. Haas himself took full advantage of the 35mm format’s strengths and was the master of capturing ephemeral moments in nature.

I do not recommend that you try photographing this close to the lava flow. I worked with permission and the guidance of a very experienced, local professional cinematographer and volcanologist. The volcanic cliffs are continually breaking off into the surf. I was at this site two consecutive evenings, and a huge shelf of hardened lava on which I stood the first evening had disappeared the next day!

When I review the photographs I made of the lava flows, I am invigorated by the memory of that powerful experience. I remember my heart pounding as I exposed roll after roll while sunset turned to darkness. It was a seminal and energizing event for me. I recall Haas’s own beautiful lava images in The Creation, when he photographed a new island formed from a volcanic eruption off the coast of Iceland. He wrote of his own experience, “It was as if we were watching a very fast and small-scale creation of the world.” Looking back with the advantage of hindsight, I see that Haas’s work helped lead me where I wanted to go, and showed me that it was possible to get there. Creation is my inspiration, and creating images of evolving Earth, my sustenance.

Lava Flow Entering the Sea at Twilight | Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Hawaii | 1994

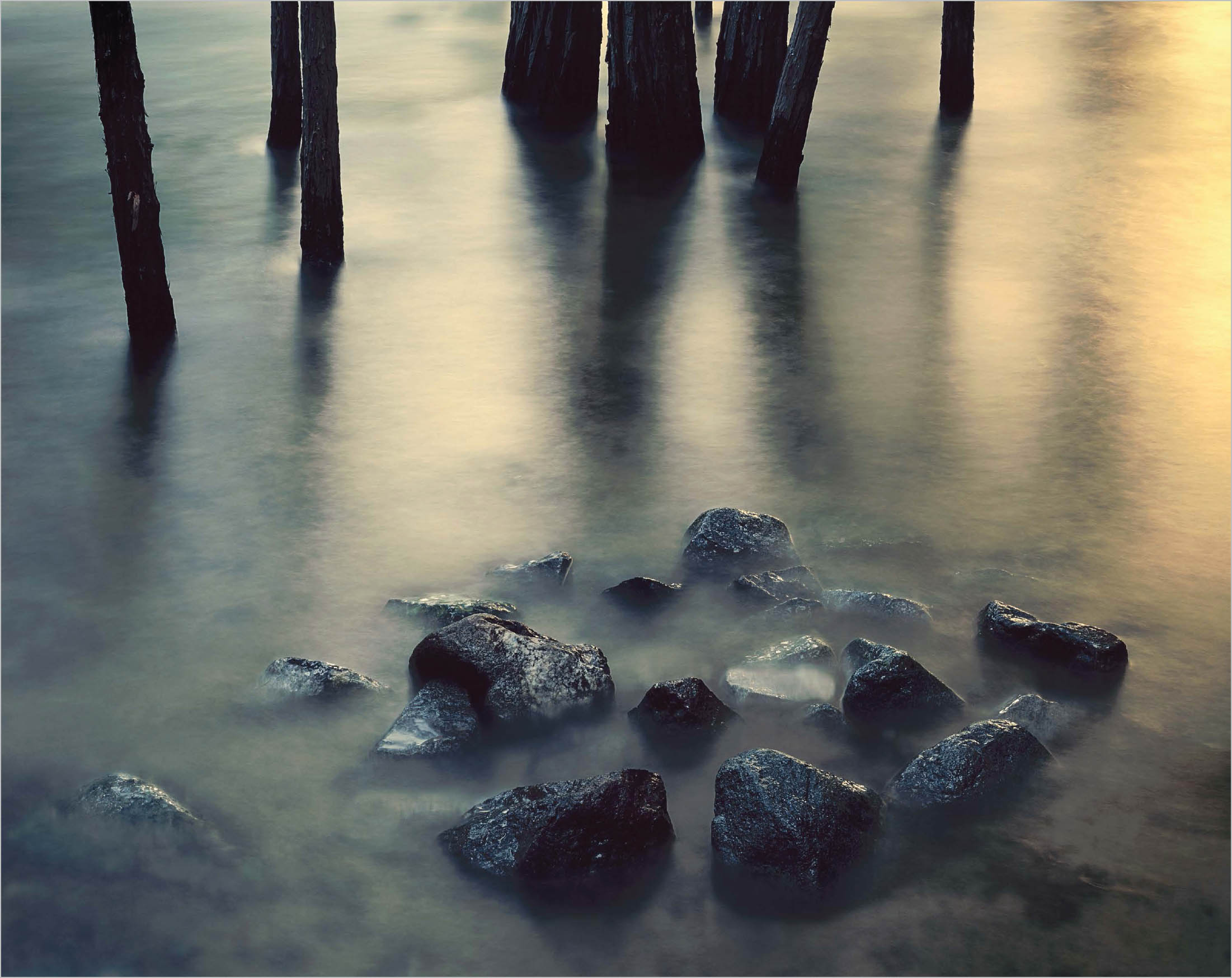

Cedar Trees and Rock Circle | Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California | 1986