OF ABSTRACT NATURE

FIND CREATIVE INSPIRATION BY FOCUSING ON DETAILS

The mind is a fascinating thing. One of the great unknowns when we share our photographs is how the viewer will respond. Once the artist has made an exposure and then edited it for presentation, a new life begins for any image shared with others. Each of us brings his or her mind, full of personal and photographic history, to the viewing process. When a scenic landscape photograph is viewed, we know where the sky is and where to “stand” in the image. But on the other end of the spectrum, when we view abstract photographs of nature, questions about orientation or scale or subject immediately come to mind. For example, I made the opening image flying over sand dunes, photographing out of a plane’s window. Few first-time viewers can guess the subject, which serves to focus full attention on the pure sensuousness of color and form.

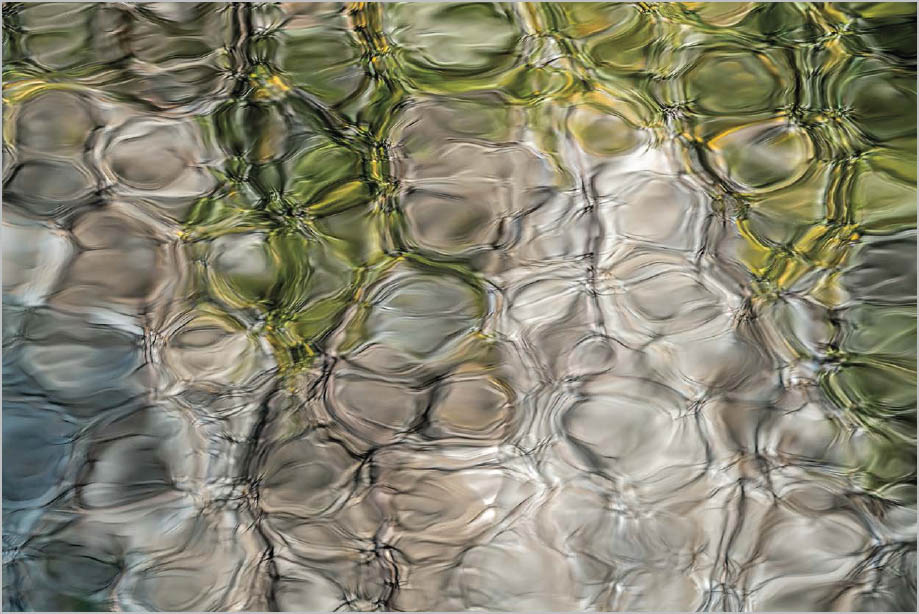

Recently I’ve been adding new images to my long-evolving series of nature abstractions. It started with clearing the overgrown rosemary shrubs away from my patio waterfall, then making ripple images once again. My very first ripple abstracts were made in 1976, at Golden Gate Canyon State Park in Colorado, where I built trails for the park. One day I sat next to a small stream as I ate my lunch and noticed the patterns of ripples in the stream. I had my camera with me, and the series began.

As I have shown these images over the years, I have enjoyed people’s reactions. The first instinct is to define the content. “What is that?” It’s as if knowing the content is required to appreciate the artist’s effort. “Ah, so it’s mud. Well then, it is beautiful, isn’t it? I had no idea what it was at first.” If I don’t tell the viewer what the subject is right away, then their imagination is activated. The mind works to solve the riddle and, in the process, the viewer gets more engaged with the composition.

The intriguing part is how differently people see an abstract photograph. “I see a face.” “I see silk fabric.” “I see an elephant!” If the questions are answered quickly, then the viewer disengages sooner. I have often watched people flip through photography books: “Ah, lovely view of the Grand Canyon . . .” Flip the page. “Wow, what great light on Half Dome that day . . . ” Flip the page. “Now what is this? Is it a rock or a tree?” If the caption is readily visible, the reader looks urgently for the answer. “Oh, of course, it is rock detail!” Flip the page.

Photographic abstractions of nature are based in reality, but are composed to give no clear reference to it. With an abstract photograph, we know the subject is real. The mind wants answers!

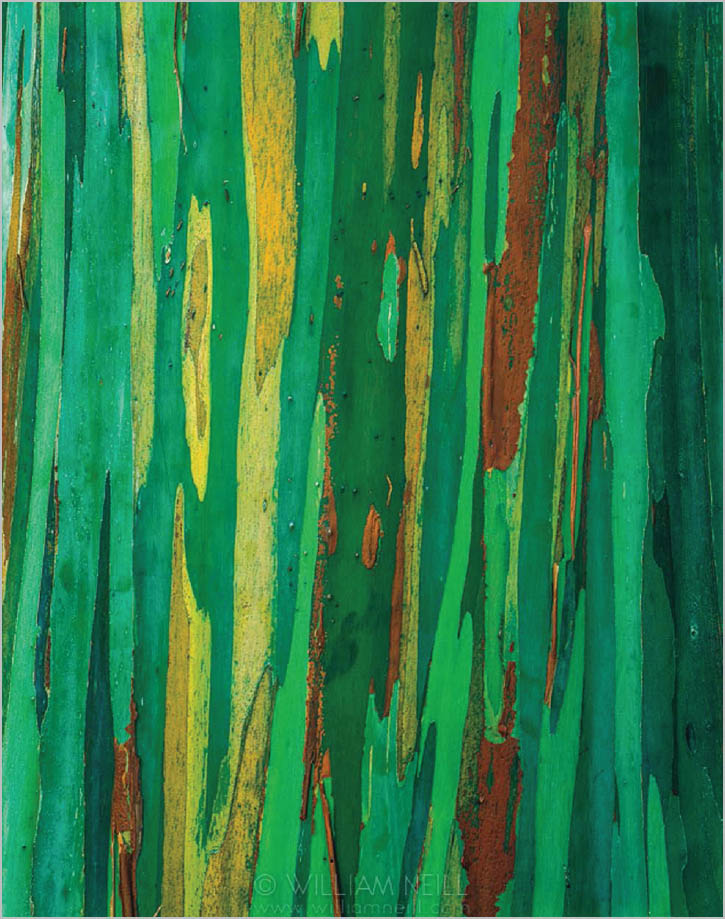

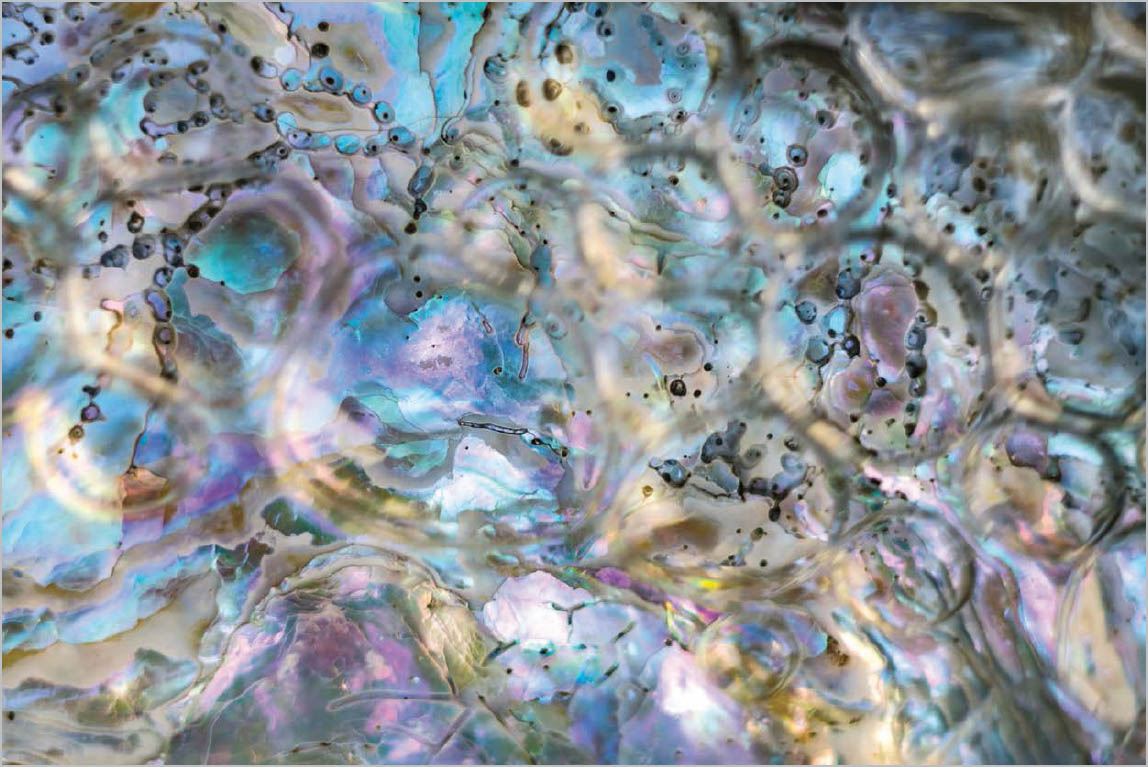

So, here are the answers for the images pictured in this essay: Photo A is eucalyptus bark. Photo B is one of the ripple images of the waterfall on my patio. Photo C is also of my waterfall, and combines an abalone shell with water and bubbles flowing over it.

Does knowing the subject help with your appreciation of each image?

I find the idea of abstract imagery to be an exciting challenge, and the results are a significant addition to the overall portrait of the landscape that I’m making with my photograph. I want my portrait of the earth to be like a symphony, sounding the many notes of the land’s diversity.

Photo A

Photo B

Photo C

Merced River Reflections, Autumn | Yosemite National Park, California | 2018