STORIES

WRITE ABOUT YOUR PHOTOGRAPHY TO BECOME A MORE POWERFUL STORYTELLER

When I first studied photography in college, the last thing I wanted to do was talk about my images. I just wanted to be outside exploring nature with my camera. My professor persisted, and so in order to pass the class, I had to define and defend my images in class. He wasn’t into landscape photography at all, and especially didn’t like Ansel Adams’s work. I was defensive about my favorite subject matter, so we clashed. Good thing I was stubborn back then. Oh yes, I still am.

So here I sit four decades later, doing what I so resisted in school: talking about my photography, or in this case, writing about it. Along the way, starting in college, I poured through photo books, and soaked up all I could glean from what the photographers had to say, especially from the photo notes often included in the back. Eventually I realized how much I was learning from this process. As I began to teach photography myself, I shared stories about how images of mine were made. I include photo notes in my own books whenever possible, and my writings are an extension of that process.

Corn Lilies | Summit Meadow, Yosemite National Park, California | 1988

Photography is a quiet, contemplative activity for me. It is a time to slow down and enjoy the beauty of the natural world. I seek to experience and reveal the mysterious, spiritual aspects of nature.

Rock, Tree, and Waterfall | Yosemite National Park, California | 2016

“Seeing and feeling beauty is more vital to me than any resulting imagery. When the key elements of photography—light, composition, and emotion—are before me, I am fully engaged, yet detached, without expectations.

The magic of my discovery—whether the dramatic light of a clearing storm or an intimate detail on the forest floor—recharges my spirit with a sense of wonder.” – from William Neill – Photographer, A Retrospective

When I look at my own work, I most enjoy recalling the overall event, such as the sounds or smells or the weather, as well as the emotion of finding the image. I don’t relish analyzing every step of process and technique, such as the decisions made in composition or metering or timing. However, one key lesson I learned from Ansel: the importance of sharing knowledge, as he set a stellar example with his workshops, books, and lectures. When I write notes for a book or write a column, I dissect my efforts for instruction’s sake in the spirit of giving back, of contributing to the tradition of landscape photography.

One time I was at Ansel’s house, and he was sitting at his IBM word processor writing for his book Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs. In this book, he relates the making of his best-known images. I wondered aloud how he could remember the details of events that occurred many decades ago. We decided that he was involved in post-rationalization (a word play on his well-known term “pre-visualization”). He laughed heartily and then assured me that he had a pretty good memory.

Way back in 1985, I hiked down Paria Canyon, which straddles the Utah-Arizona border. I knew little about the trip, except that the best way to see the photogenic narrows of the canyon was to backpack, taking a few days to walk downstream to the Colorado River. It was a spur-of-the-moment trip and so I decided to take a long day hike in hopes of seeing the best parts. It was October, so the river was fairly low. I walked alongside it trying to keep my feet dry until I had crossed so many times that I just waded down the river, shoes on and full of sand and pebbles. I found a few photographs along the way, but pressed on into the deeper part of the canyon. I wasn’t prepared to camp, so finally, feeling unrewarded, I turned around and headed back upstream late in the afternoon.

Of course, that was when I started seeing many images to photograph. The afternoon sun was shining far up the canyon wall and reflecting beautifully in the river. The contrast range of the light was wide, so I looked for compositions that fit within the film’s latitude. The image that opens this essay does not show the whole scope of the scene, with bright canyon walls and deep-blue desert sky. But by cropping out the sunlit walls and the sky, the contrast was manageable, and the reflections glow out from the shadowed canyon and become the central emphasis. Without knowing the context of the whole scene, the viewer has to imagine the source of light and the height of the walls.

By the time I was finished making images, it was late afternoon with several hours of hiking to go. When I came out of the canyon, it was dark, and finding the path to the trailhead parking lot was an adventure. Hey, I was only lost for about an hour! And yes, I had a flashlight; it’s just that there were no trail signs in the river . . .

We all have stories to tell about our photographs. Sometimes the stories are directly about the actual making of the photograph, such as a creative exposure solution or an unusual camera angle. Sometimes stories reveal the photographer’s experience, unseen in the image, but when heard, they make the photograph all the more special.

From your stories, you may discover themes for an exhibit, portfolio, book, or slide show because they often reveal what is most important to you. Think about what stories you repeatedly tell with excitement. With your stories and images combined, their collective story can powerfully convey a message, be it simply how much fun you had on a photo tour, or more seriously, why you think a wild corner of your state should be preserved. If you are serious about marketing your images, it doesn’t hurt to develop your writing or lecturing skills in order to better tell your tales.

Ultimately, a photograph must stand on its own, and tell its own story regardless of the context or any words written about it. Ansel once wrote, “A true photograph need not be explained, nor can it be contained in words.” The key is that your image reconnects you, and hopefully connects the viewer, to your experience. First and foremost, make an image that needs no words. Then if you can expand and deepen the message with your stories, all the better.

I asked Ansel once, as a photographer concerned with the environment, what he felt was more helpful for the cause: making an artistic image for its own sake or making an image in order to illustrate an environmental issue. He answered: Make your art. Your most deeply felt and seen images will reach people’s hearts and change minds!

By the time I graduated from college, I had already decided to forsake a traditional path of employment and become a photographer. My father, who was a writer, suggested that it might help if I learned to combine writing along with my photographs. From his career as a journalist, he knew that combining image and word was often the most powerful way to communicate a story; that being able to do both added value and opportunity to my efforts. As a young man, I resisted, wanting my photographs to speak for themselves. Eventually, I came around to my dad’s suggestion. The emotions and experiences arising from my visual explorations began to formulate in my head, and through teaching, I discovered I had something I wanted to say, in words as well as images.

My first opportunity to write in depth about my work was for Outdoor Photographer magazine in 1986. The essay I wrote was entitled “Intimate Landscapes.” The essay has endured for me, still ringing true, and the key ideas have formed my artist’s statement ever since. The article’s title pays homage to Eliot Porter’s book of the same name, and to the inspiration of his photographs. I open the essay with these words: “Photography is a quiet, contemplative activity for me. It is a time to slow down and enjoy the beauty of the natural world. I seek to experience and reveal the mysterious, spiritual aspects of nature.” See “The Intimate Landscape” on page 21 for more discussion of this subject.

To help clearly define your personal point of view, it is useful to give a meaningful title to your portfolios. A clear and concise title of your portfolio is vital. Depending on the audience or intent, the theme could be named descriptively, such as the name of the subject or location. Your potential viewer will literally know what to expect. For a series representing your most artistic work, a poetic or conceptual title will entice the potential audience to look further. At the very least, a subject or style should be communicated. Examples I’ve used include “Landscapes of the Spirit,” “Meditations in Monochrome,” and “Impressions of Light.” Each of them gives a sense of the mood or style by which I organized the portfolios. The right words can trigger curiosity and anticipation for what is within.

Of course, the words we might use to describe our images don’t make the photo successful. Each photograph should stand alone on its own merit. However, good writing can explain, amplify, and expand the viewer’s understanding of the photographer’s philosophy, passions, and point of view.

If you spend much time online, you know we are inundated daily by images on social media and blogs, eBooks and eZines. Most of the superstars of social media are making excellent photographs. Although much of social media emphasizes the image far more than the words, if you dig under the surface, you can discover the intriguing details of a photographer’s experience, their history and philosophy. I urge you to look deeper into those photographers that inspire you.

Guy Tal is one photographer who has embraced both word and image. Coincidentally we happened to be corresponding as I was writing this essay. When I mentioned my essay’s theme, he shared these words: “I think that any creative artist must have an understanding, first of all, of what s/he wishes to express, and [should] then pick the best medium for it based on his personal taste and skills. To me, photography came after writing, and I realized early on that the two play complementary roles in my life, and that I had to do both to express what I find important and noble. Photography for me is a way of exploring the world outside myself, and then to overlay personal meaning on it. Writing for me is a way of exploring my inner thoughts and feelings, and then to overlay elements of the external world that elicit these thoughts and feelings.”

If you haven’t already, write an artist’s statement, find the themes about which you are most passionate, frame them with enticing titles, and help distinguish your own photography with words to define your own perspective.

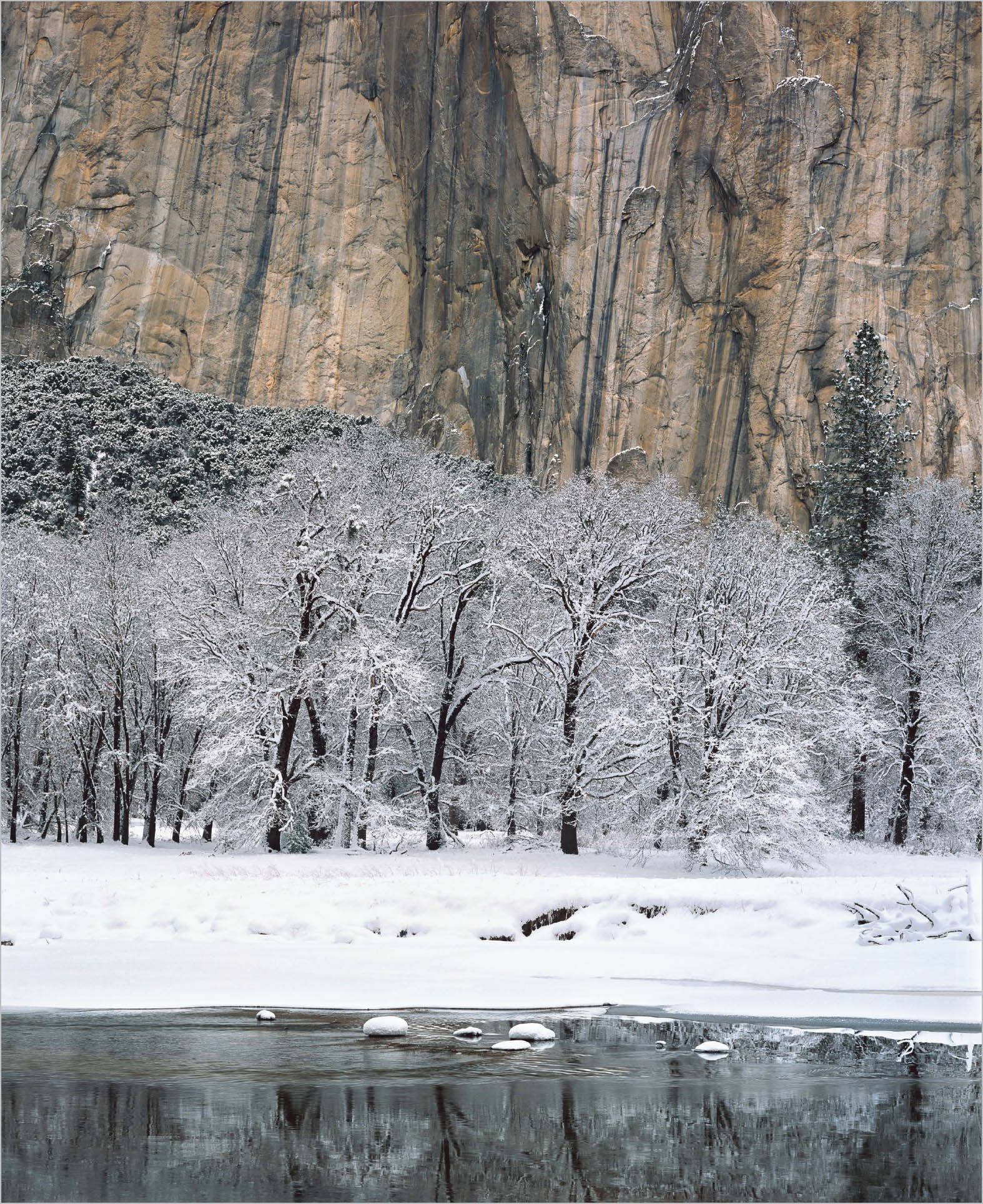

Black Oaks | Merced River and El Capitan, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, California | 1985

“From within these [Yosemite’s] protected walls, the peacefulness and beauty bring comfort and calm to me. Given this sense of sanctuary, my creative energies have been given the freedom to express what I feel, to express the connection between my spirit and the beauty of Creation.” – from William Neill – Photographer, A Retrospective