On June 16, 23 and 30, 1961, broadly representative meetings of Cuba’s intellectuals and cultural figures were held in the auditorium of the National Library in Havana. Artists and writers had the opportunity to discuss at length different aspects of cultural work and problems related to creative activity. Present at these meetings were President Osvaldo Dorticós, Prime Minister Fidel Castro, Minister of Education Armando Hart, members of the National Council of Culture and other representatives of the revolutionary government. At the last session, Fidel argued “within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing.”

Compañeros;

Compañeras:

Over the course of three sessions, various issues relating to culture and creative work have been discussed. Many interesting questions have been raised and different points of view expressed. Now it is our turn. I am not speaking because I’m the best-qualified person to deal with this matter, but because this is a meeting between you and us, we feel it is necessary to express our point of view.

We have been very interested in these discussions, and I believe we have shown what might be called “great patience.” Actually no heroic effort was necessary; for us it has been an enlightening discussion and, in all sincerity, a pleasant experience. Of course, in this type of discussion we, the members of the government, are not the most qualified people to be expressing opinions on issues you specialize in. At least, that is true for me…

We have been active participants in this revolution, the social and economic revolution taking place in Cuba. At the same time, this social and economic revolution will inevitably produce a cultural revolution in our country.

We have tried to do something in this field (although perhaps there were more pressing problems to deal with at the beginning of the revolution). If we were to review our efforts with a critical eye, it could be said we have somewhat neglected a discussion as important as this one. Not that it was forgotten completely. The government was already considering a discussion like this, and perhaps the incident referred to repeatedly here helped speed things up. Months ago we intended to call a meeting like this one to review and discuss the question of culture. But important events kept taking place, one after the other, and the latest ones especially prevented this from taking place earlier. The revolutionary government has adopted a few measures that express our concern over this question. A few things have been done, and several members of the government have brought the question up more than once. In any case, it can be said that the revolution itself has already brought about changes in the cultural sector, and that the artists’ conditions of work have changed.

I believe that a pessimistic perspective has been somewhat overemphasized here. Concerns have been expressed that go far beyond what can really be justified. The reality of the changes that have occurred in this sector and in the actual conditions for artists and writers has been almost ignored in the discussion. It is unquestionable that things are better for Cuban artists and writers than in the past, when their conditions were truly depressing. If the revolution started off by bringing about profound changes in the environment and conditions of work, why should we fear that the same revolution would seek to destroy those changes? Why should we fear that the revolution would destroy the very conditions it created?

What we are discussing here is not a simple problem. All of us here have the responsibility to analyze it carefully. It is not a simple problem, it has arisen many times in all revolutions. It is a knotty problem, we might say, and it is not easy to untangle. Nor is it one we are going to solve easily.

The various compañeros who have spoken here expressed a great variety of points of view, and they gave their reasons for them. The first day, people were a little timid, and for this reason, we had to ask the compañeros to tackle the subject directly, to have everyone state their concerns openly.

If we are not mistaken, the fundamental question raised here is that of freedom of artistic creation. When writers from abroad have visited our country, political writers in particular, this question has been brought up more than once. It has undoubtedly been a subject of discussion in every country where a profound revolution like ours has taken place.

By chance, shortly before we returned to this hall, a compañero brought us a pamphlet containing a brief conversation on this subject between [Jean-Paul] Sartre and myself that Lisandro Otero included in the book entitled Conversations at the Lake [Revolución, Tuesday, March 8, 1960]. I was asked a similar question on another occasion by C. Wright Mills, the US writer.

I must confess that in a certain way these questions caught us a little unprepared. We did not have our “Yenan conference” with Cuban artists and writers during the revolution. In reality, this is a revolution that arose and came to power in what might be called record time. Unlike other revolutions, it did not have the main problems resolved.

Therefore, one of the revolution’s characteristics has been its need to confront many problems under the pressure of time. We are just like the revolution, that is, we have improvised quite a bit. This revolution has not had the period of preparation that other revolutions have had, and the leaders of this revolution have not had the intellectual maturity that leaders of other revolutions have had. Yet I believe that we have contributed to current developments in our country as much as has been in our power. I believe that through everyone’s efforts, we are carrying out a true revolution, and that this revolution is developing and seems destined to become one of the important events of the century.

We have had an important part in these events, however we do not consider ourselves revolutionary theoreticians or revolutionary intellectuals. If people are judged by their deeds, perhaps we might have the right to consider the revolution itself to be our merit. But we do not think so, and I believe that we should all adopt a similar attitude, regardless of the work we might have done. Whatever merits our work may appear to have, we should begin by honestly placing ourselves in the position of not presuming that we know more than anyone else; that we know all there is to know; that our viewpoints are infallible; and that everyone who does not think exactly as we do is mistaken. We should honestly evaluate—although not with false modesty—what we know. I believe it will be easier to progress in this way and with confidence. If all of us adopt that attitude—you as well as us—subjective attitudes will disappear, and the element of subjectivity in analyzing problems will disappear too. What do we really know, in fact? We are all learning and we all have much to learn. We have not come here to teach; we have also come to learn.

There have been certain fears floating about, expressed by some compañeros. Listening to them, we felt at times that we were dreaming. We had the impression that our feet were not firmly planted on the ground—because if we have any fears or concerns today, they are connected with the revolution itself. The great concern, for all of us, should be the revolution. Or do we believe that the revolution has already won all its battles? Do we believe that the revolution is not in danger? What should be the first concern of every citizen today? Should it be concern that the revolution is going to commit excesses; that the revolution is going to stifle art or that the revolution is going to stifle the creativity of our citizens—or should it be the revolution itself? Should our first concern be the dangers, real or imaginary, that might threaten that creative spirit, or should it be the dangers that might threaten the revolution?

We are not invoking this danger as a simple point of argument. We are saying that the concern of the country’s citizens and of all revolutionary writers and artists—or of all writers and artists who understand the revolution and consider it just—should be: What dangers threaten the revolution and what can we do to help the revolution? We believe that the revolution still has many battles to fight, and that our first thoughts and our first concerns should be: What can we do to assure the victory of the revolution? That comes first. The first thing is the revolution itself, and then, afterwards, we can concern ourselves with other questions. This does not mean that other questions should not concern us, but that the fundamental concern in our minds—as it is with me—has to be the revolution.

The question under discussion here and that we will tackle is the question of the freedom of writers and artists to express themselves.

The fear in people’s minds is that the revolution might choke this freedom, that the revolution might stifle the creative spirit of writers and artists.

Freedom of form has been spoken of. Everyone agrees that freedom of form must be respected; I believe there is no doubt on this point.

The question becomes more delicate, and we get to the real heart of the matter, when dealing with freedom of content. This is a much more delicate issue, and it is open to the most diverse interpretations. The most controversial aspect of this question is: Should we or should we not have absolute freedom of content in artistic expression? It seems to us that some compañeros defend the affirmative. Perhaps it is because they fear that the question will be decided by prohibitions, regulations, limitations, rules and the authorities.

Permit me to tell you in the first place that the revolution defends freedom. The revolution has brought the country a very high degree of freedom. By its very nature, the revolution cannot be an enemy of freedom. If some are worried that the revolution might stifle their creativity, that worry is unnecessary, there is no basis for it whatsoever.

What could be the basis for such a concern? Only those who are unsure of their revolutionary convictions can be truly worried about such a problem. Someone who lacks confidence in their own art, who lacks confidence in their ability to create, might be worried about this matter. Should a true revolutionary, an artist or an intellectual who feels the revolution is just and is sure that they are capable of serving the revolution, worry about this problem? Should truly revolutionary writers and artists hold any doubts? My opinion is no—the only ones who could hold any doubts are those writers and artists who, without being counterrevolutionaries, are not revolutionaries either.

It is correct for writers or artists who do not feel themselves to be true revolutionaries to pose this question. An honest writer or artist, who is capable of grasping the revolution’s purpose and sense of justice without being part of it, should consider this question.

A revolutionary puts one thing above all else. A revolutionary puts one thing above even their own creativity; they put the revolution above everything else. And the most revolutionary artist is one who is ready to sacrifice even their own artistic calling for the revolution.

No one has ever assumed that every person, every writer or every artist has to be a revolutionary, just as no one should ever assume that every person or every revolutionary has to be an artist, or that every honest person, just because they are honest, has to be a revolutionary. Being a revolutionary is to have a certain attitude toward life. Being a revolutionary is to have a certain attitude toward existing reality. There are some who resign themselves and adapt to this reality, and there are others who cannot resign or adapt themselves to that reality but who try to change it. That’s why they are revolutionaries.

There can also be some who adapt themselves to reality who are honest people—it is just that their spirit is not a revolutionary spirit; their attitude toward reality is not a revolutionary attitude. Of course, there can be artists, and good artists, who do not have a revolutionary attitude toward life, and it is precisely this group of artists and intellectuals for whom the revolution constitutes something unforeseen, something that might deeply affect their state of mind. It is precisely this group of artists and intellectuals for whom the revolution constitutes a problem.

For a mercenary artist or intellectual, for a dishonest artist or intellectual, this would never be a problem. They know what they have to do, they know what is in their interest, they know where they are going.

The real problem exists for the artist or intellectual who does not have a revolutionary attitude but who is an honest person. Obviously, a person who has such an attitude toward life, whether or not they are a revolutionary, whether or not they are an artist, has their own goals and objectives. We should all ask ourselves about such goals and objectives.

For the revolutionary, those goals and objectives are directed toward changing reality and toward the redemption of humanity. It is humanity itself, one’s fellow human being, the redemption of one’s fellow human being that constitutes the revolutionary’s objective. If we revolutionaries are asked what matters most to us, we will say: The people, and we will always say the people. The people in their true sense, that is, the majority of those who have had to live under exploitation and the cruelest neglect. Our fundamental concern will always be with the great majority of the people, the oppressed and exploited classes. We view everything from this standpoint: Whatever is good for them will be good for us; whatever is noble, useful and beautiful for them, will be noble, useful and beautiful for us. If one does not think in this manner, if one does not think of the people and for the people, if one does not think and act for the great exploited mass of the people, for the great masses we seek to redeem, then one simply does not have a revolutionary attitude.

From this standpoint we analyze what is good, what is useful and what is beautiful.

We understand that it must be a tragedy when someone understands this and nevertheless has to confess that he or she is incapable of fighting for it.

We are, or believe ourselves to be, revolutionaries. Whoever is more an artist than a revolutionary cannot think in exactly the same way that we do. We suffer no inner conflict, because we fight for the people and we know that we can achieve the objectives of our struggle. The principal goal is the people. We have to think about the people before we think about ourselves—that is the only attitude that can be defined as truly revolutionary. It is for those who cannot or do not have such an attitude, but who are honest people, that this problem exists. And just as the revolution constitutes a problem for them, they constitute a problem the revolution should be concerned about.

The case was well made here that there are many writers and artists who are not revolutionaries, but who are nevertheless sincere writers and artists. It was stated that they wanted to help the revolution, and that the revolution is interested in their help; that they wanted to work for the revolution and that for its part, the revolution had an interest in them contributing their knowledge and efforts on its behalf.

It is easier to appreciate this by analyzing specific cases, and some of these are difficult. A Catholic writer spoke here, raising problems that concerned him and he spoke with great clarity. He asked if he would be able to write on a particular question from his ideological point of view, or if he would be able to write a work defending that point of view. He asked quite frankly if, within a revolutionary system, he could express himself in accordance with his beliefs. He thus posed the problem in a way that might be considered symptomatic.

He wanted to know if he could write in accordance with those beliefs or that ideology, which is not exactly the ideology of the revolution. He was in agreement with the revolution on economic and social questions, but his philosophical position was different from that of the revolution. It is worth keeping this case in mind, because it is representative of the type of writers and artists who demonstrate a favorable attitude toward the revolution, and wish to know what degree of freedom they have within the revolution to express themselves in accordance with their beliefs.

This is the sector that constitutes a problem for the revolution, just as the revolution constitutes a problem for them. It is the duty of the revolution to concern itself with these cases. It is the duty of the revolution to concern itself with the situation of these artists and writers, because the revolution should strive to have more than just the revolutionaries march alongside it, and more than just the revolutionary artists and intellectuals.

It is possible that women and men who have a truly revolutionary attitude toward reality are not the majority of the population. Revolutionaries are the vanguard of the people, but revolutionaries should strive to have all the people march alongside them. The revolution cannot renounce the goal of having all honest men and women, whether or not they are writers and artists, march alongside it. The revolution should strive to convert everyone who has doubts into revolutionaries. The revolution should try to win over the majority of the people to its ideas. The revolution should never give up relying on the majority of the people. It must rely not only on the revolutionaries, but on all honest citizens who, although they may not be revolutionaries—who may not have a revolutionary attitude toward life—are with the revolution. The revolution should turn its back only on those who are incorrigible reactionaries, who are incorrigible counterrevolutionaries.

The revolution must have a policy and a stance toward this sector of the population, this sector of intellectuals and writers. The revolution has to understand this reality and should act in such a way that these artists and intellectuals who are not genuine revolutionaries can find a space within the revolution where they can work and create. Even though they are not revolutionary writers and artists, they should have the opportunity and freedom to express their creative spirit within the revolution.

In other words: Within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing. Against the revolution, nothing, because the revolution also has its rights, and the first right of the revolution is the right to exist, and no one can oppose the revolution’s right to exist. Inasmuch as the revolution embodies the interests of the people, inasmuch as the revolution symbolizes the interests of the whole nation, no one can justly claim a right to oppose it.

I believe that this is quite clear. What are the rights of writers and artists, revolutionary or nonrevolutionary? Within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, there are no rights.

This is not some special law or guideline for artists and writers. It is a general principle for all citizens. It is a fundamental principle of the revolution. Counterrevolutionaries, that is, the enemies of the revolution, have no rights against the revolution, because the revolution has one right: the right to exist, the right to develop, and the right to be victorious. Who can cast doubt on that right, the right of a people who have said, “Patria o muerte!” [Homeland or death!], that is, revolution or death.

The existence of the revolution, or nothing. This is a revolution that has said, “Venceremos!” [We will win!]. It has very seriously stated its intention. And as much as one may respect the personal reasons of an enemy of the revolution, the rights and the welfare of a revolution must be respected more. This is even more true in light of the revolution being a historical process, inasmuch as a revolution is not and cannot be the product of a whim or of the will of a single individual. A revolution can only be the product of the needs and the will of the people. In the face of the rights of an entire people, the rights of the enemies of the people do not count.

We speak of extreme cases only in order to express our ideas more clearly. I have already said that among those extreme cases there is a great variety of attitudes and there is also a great variety of concerns. To hold a particular concern does not necessarily signify that one is not a revolutionary. We have tried to define basic attitudes.

The revolution cannot seek to stifle art or culture since one of the goals and fundamental aims of the revolution is to develop art and culture, precisely so that art and culture truly become the patrimony of the people. Just as we want a better life for the people in the material sense, so too do we want a better life for the people in a spiritual and cultural sense. Just as the revolution is concerned with the development of conditions that will let the people satisfy all their material needs, so too do we want to develop conditions that will permit the people to satisfy all their cultural needs.

Do our people have a low cultural level? Do a high percentage of the people not know how to read and write? A high percentage of our people have also known hunger, or live or have lived in very difficult conditions, in conditions of extreme poverty. A section of the population lacks a great many of the material goods they need, and we are trying to bring about conditions that will give those people access to all these material goods.

In the same way, we should bring about the necessary conditions so that works of culture reach the people. This does not mean that an artist has to sacrifice the artistic value of their creations, or the quality. It means that we all have to struggle so that the artist creates for the people, so that, in turn, the people’s cultural level is raised and they draw nearer to the artist.

We cannot establish a general rule. All artistic expressions are not exactly the same, and at times we have spoken here as if that were the case. There are expressions of the creative spirit that by their very nature are much more accessible to the people than other manifestations of the creative spirit. Therefore it is impossible to establish a general rule. What type of expression should the artist follow in an effort to reach the people, and in what ways will the people draw nearer to the artist? Can we make a general statement about this? No, it would be an oversimplification. It is necessary to strive to reach the people with all creative expressions, but at the same time it is necessary to do everything we can to enable the people to understand more and to understand better. I believe that this principle does not conflict with the aspirations of any artist—and much less so if it is kept in mind that people should create for their contemporaries.

Don’t say that there are artists who create only for posterity, because without considering our judgment infallible, I believe that anyone proceeding on this assumption is deluding themselves. That is not to say that artists who work for their contemporaries have to renounce posterity, because it is precisely by creating for one’s contemporaries—whether or not one’s contemporaries understand them—that works acquire historic and universal value. We are not making a revolution for the generations to come, we are making a revolution with this generation and for this generation, independently of the fact that it benefits future generations and may become a historic event. We are not making a revolution for posterity; this revolution will be important to posterity because it is a revolution for today, and for the men and women of today.

Who would support us if we were making a revolution for future generations? We are working and creating for our contemporaries, without depriving any artistic endeavor of its aspiration to eternal fame.

These are truths that we should all analyze with honesty. And I believe it is necessary to start from certain basic truths in order to avoid false conclusions. We do not see how any honest artist or writer has reason for concern.

We are not enemies of freedom. No one here is an enemy of freedom. Whom do we fear? What authority do we fear will stifle our creativity? Do we fear our compañeros in the National Council of Culture? In talks we have held with members of the National Council of Culture we have observed feelings and viewpoints that are far removed from the concerns expressed here about limitations, straitjackets and so on, imposed on creativity.

Our conclusion is that the compañeros of the National Council of Culture are as concerned as all of you are about achieving the best conditions for the development of creative work by artists and intellectuals. It is the duty of the revolution and the revolutionary government to see that there is a highly qualified agency that can be relied upon to stimulate, encourage, develop and guide—yes, guide—that creative spirit; we consider it a duty. Does this perhaps constitute an infringement on the rights of writers and artists? Does this constitute a threat to the rights of writers and artists, implying that there will be arbitrary measures or an excess of authority? It would be the same as being afraid that the police will attack us when we pass a traffic light. It would be the same as being afraid that a judge will condemn or sentence us, the same as being afraid that the forces of the revolutionary power will commit some act of violence against us.

In other words, we would then have to worry about all these things. And yet our citizens do not believe that the militia is going to fire at them, that the judge is going to punish them, that the state power is going to use violence against them.

The existence of an authority in the cultural sector does not mean that there is any reason to worry about that authority being abused. Does anyone think that such a cultural authority should not exist? By the same token, one could think that the militia should not exist, that the police should not exist, that the state power should not exist, and even that the state should not exist. And if anyone is so anxious for the disappearance of the slightest trace of state authority, then let them stop worrying, be patient, for the day will come when the state will not exist either.

There has to be a council that guides, that stimulates, that develops, that works to create the best conditions for the work of the artists and intellectuals. What organization is the best defender of the interests of the artists and intellectuals if not this very council? What organization has proposed laws and suggested various measures to improve those conditions, if not the National Council of Culture? What organization proposed a law to create the National Printing House to remedy the deficiencies that have been pointed out here? What organization proposed the creation of the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore, if not the National Council of Culture? What organization has advocated the allocation of the funds and the foreign currency necessary for importing books that had not entered the country in many months; for buying material so that painters and plastic artists can work? What organization has concerned itself with the economic problems, that is, with the material conditions of the artists? What organization has concerned itself with a whole range of current needs of writers and artists? What organization has defended within the government the budgets, the buildings and the projects directed at improving your working conditions? That organization is none other than the National Council of Culture.

Why should anyone view that council with suspicion? Why should anyone fear that it will use its authority to do exactly the opposite: limit our conditions, stifle our creativity?

It is conceivable that some people who have had no problems at all are concerned about that authority. But those who appreciate the necessity of all the steps the council has had to take, and all the work it has to do, can never look at it with suspicion, because the council also has an obligation to the people and it has an obligation to the revolution and to the revolutionary government. And that obligation is to fulfill the objectives for which it was created, and it has as much interest in the success of its work as each artist has in their own success.

I don’t know if I have failed to touch on some of the fundamental questions that were raised here. There was much discussion on the question of the film [“Pasado Meridiano” or “PM” by Cuban filmmakers Orlando Jiménez and Sabá Cabrera]. I have not seen the film, although I want to see it. I am curious to see it. Was the film dealt with unfairly? In fact, I believe that no film has received so many honors or been discussed so much.

Although I have not seen that movie, I have heard the opinions of compañeros who have seen it, including the president and various members of the National Council of Culture. At the very least, their opinion, their judgment, merits respect from us all. But there is one thing I believe cannot be disputed, and that is the right established by law to exercise the function that was exercised in this case by the Film Institute or the Review Board. Perhaps that right of the government is being disputed? Does the government have the right to exercise that function or not? For us, what is fundamental in this case is, above all, to determine if the government did or did not have that right. The question of procedure could be discussed, as it was, to determine if it was fair or not, if another, more amicable procedure would have been better, if the decision was just or not. But there is one thing I believe no one can dispute, and that is the government’s right to exercise that function. For if we challenge that right, then it would mean that the government does not have the right to review the films that are going to be shown to the people.

I believe this is a right that cannot be disputed. There is, in addition, something that we all understand perfectly, and this is that some intellectual or artistic creations are more important than others as far as the education or the ideological development of the people is concerned. I don’t believe anyone can disagree that among the most fundamental and highly important media is the cinema, as well as television. Now, in the midst of the revolution, can anyone challenge the government’s right to regulate, review and supervise the films that are shown to the people? Is this, perhaps, what is being disputed?

Can the revolutionary government’s right to supervise the mass media that influence the people so much be considered a limitation or a prohibition? If we were to challenge that right of the revolutionary government, we would be faced with a problem of principle, because to deny that right to the revolutionary government would be to deny the government’s function and responsibility, especially in the midst of a revolutionary struggle, in leading the people and leading the revolution. At times, it has seemed that this right of the government was being challenged; and in response, we state our opinion that the government does have such a right. And if it has that right, it can make use of that right. It can make mistakes; we are not pretending that the government is infallible. The government, in exercising its right or its functions, is not required to be infallible. But can anyone be so skeptical, so suspicious, and so distrustful toward the revolutionary government that in believing one decision is wrong, they are terror-stricken that the government might always be wrong?

I am not suggesting the government was mistaken in that decision. What I am saying is that the government exercised its right. I am trying to put myself in the place of those who worked on that film. I am trying to put myself in their state of mind, and I am even trying to understand their sorrow, unhappiness and pain when the film was not shown. That is perfectly understandable. But one must understand that the government acted within its rights. This judgment had the support of competent and responsible members of the government, and there is no reason for distrusting the spirit of justice and fairness of the members of the revolutionary government, because the revolutionary government has given no cause for anyone to doubt its spirit of justice and fairness.

We should not think that we are perfect, we should not even think that we are free of subjectivity. Some people might point out that certain compañeros in the government are subjective, or not free of subjectivity. Can those who believe this assure us that they themselves are completely free of subjectivity?

Can they accuse some compañeros of holding subjective views without accepting the fact that their own opinions might also be influenced by subjective factors? Let us state here that whoever feels themselves perfect or free from subjectivity should cast the first stone.

I believe there has been a personal and emotional element in the discussion. Hasn’t there been a personal and emotional element in the discussion? Did absolutely everyone come here free of emotionalism and subjectivity? Did absolutely everyone come here free of any group spirit? Are there no currents and tendencies within this discussion? There undoubtedly are. If a six-year-old child had been seated here, he or she too would have noticed the different currents and viewpoints, the different emotions that were confronting one another.

People here have said many things. They have said interesting things. Some have said brilliant things. Everyone has been very “erudite.” But, above all, there has been a reality, the reality of the discussion itself and the freedom with which everyone has been able to express themselves and defend their point of view. The freedom with which everyone has been able to speak and explain their views in the midst of a large meeting, which has grown larger by the day, a meeting that we consider positive, where we have been able to dispel a whole series of doubts and worries. Have there been quarrels? Undoubtedly. Have there been battles and skirmishes here among the writers and artists? Undoubtedly. Has there been criticism and supercriticism? Undoubtedly. Have some compañeros tried out their weapons at the expense of other compañeros? Undoubtedly.

The wounded have spoken here, expressing their complaints at what they consider unjust attacks. Fortunately, we’ve had no dead, only wounded, including compañeros who are still convalescing from their wounds. And some of them presented as a clear case of injustice the fact that they had been attacked with high-caliber artillery without ever having had the chance to return fire. Have harsh criticisms been made? Undoubtedly!

In a certain sense a problem has been raised here that we are not going to pretend to be able to address in a few words. But I believe that among the things said here, one of the most correct is that the spirit of criticism should be constructive; it should be positive and not destructive. That’s what we believe. But, in general, that is not kept in mind. For some, the word “criticism” has become a synonym for “attack,” when it really means nothing of the sort. When they tell someone, “So-and-so criticized you,” the person gets angry before even asking what was really said. In other words, he or she assumes they were torn apart.

If those of us who have been somewhat removed from these problems or struggles—these skirmishes and weapons tests—were told about the cases of certain compañeros who have almost been on the verge of deep depression because of devastating criticism leveled against them, it is quite possible that we would sympathize with the victims, because we have a tendency to sympathize with victims. We who sincerely want only to contribute to an understanding and unity among everyone have tried to avoid words that could wound or discourage anyone.

One thing is unquestionable, however: There may have been struggles or controversies in which conditions have not been equal for everyone. From the point of view of the revolution, this cannot be fair. The revolution should not give weapons to some to be used against others. We believe that writers and artists should have every opportunity to express themselves. We believe that writers and artists, through their association, should have a broad cultural magazine open to all. Doesn’t it seem to you this would be a fair solution? But the revolution cannot put those resources in the hands of one particular group. The revolution can and should marshal those resources in such a manner that they can be widely utilized by all writers and artists.

You will shortly constitute an association of writers and artists [UNEAC] at the congress you will attend. That congress should be held in a truly constructive spirit, and we are confident that you are capable of holding it in that spirit. From that congress will emerge a strong association of writers and artists where everyone who has a truly constructive spirit can take part. If anyone thinks we wish to eliminate them, if anyone thinks we want to stifle them, we can give assurances that they are absolutely mistaken.

Now is the time for you to contribute in an organized way and with all your enthusiasm to the tasks corresponding to you in the revolution, and to constitute a broad organization of all writers and artists. I don’t know if the questions that have been raised here will be discussed at the congress, but we know that the congress is going to meet, and that its work—as well as the work to be done by the association of writers and artists—will be good topics for discussion at our next meeting.

We believe that we should meet again; at least, we don’t want to deprive ourselves of the pleasure and usefulness of these meetings, which have served to focus our attention on all these questions. We have to meet again. What does that mean? That we have to continue discussing these questions. In other words, everyone can rest assured that the government is greatly interested in these questions, and that the future will hold ample opportunity for discussing all these questions at large meetings. It seems to us that this should be a source of satisfaction for writers and artists, and we, too, look forward to acquiring more information and knowledge.

The National Council of Culture should also have an information agency. I think that this is putting things in their proper place. It cannot be called cultural imposition or a stifling of artistic creativity. What true artist with all his or her senses could think that this constitutes a stifling of creativity? The revolution wants artists to exert the maximum effort on behalf of the people. It wants them to put the maximum interest and effort into revolutionary work. We believe this is a just aspiration of the revolution.

Does this mean that we are going to tell the people here what they have to write? No. Everyone should write what they want, and if what they write is no good, that’s their problem. If what they paint is no good, that’s their problem. We do not prohibit anyone from writing on the topic they prefer. On the contrary, everyone should express themselves in the form they consider best, and they should express freely the idea they want to express. We will always evaluate a person’s creation from the revolutionary point of view. That is also the right of the revolutionary government, which should be respected in the same way that the right of each person to express what he or she wants to express should be respected.

A series of measures are being taken, some of which we have mentioned. We wish to inform those who were concerned about the question of the National Printing House that a law is under consideration to regulate its functions, to create various editorial divisions in line with different publishing needs and to overcome the deficiencies existing at present. The National Printing House is a recently created organization that has emerged under difficult conditions. It had to begin working in the offices of a newspaper that was closed suddenly (we were present the day that newspaper plant became the largest print shop in the country, with all its workers and editors), and it had to carry out the publication of urgently needed works, including many of a military nature. The National Printing House does have deficiencies, but these will be remedied. There will be no grounds for complaints such as those expressed here, in this meeting, about the National Printing House. Measures are also being taken to acquire books, to acquire work materials, that is, to resolve all the problems that have concerned writers and artists and which the National Council of Culture has repeatedly pointed to. For as you know, the state has different departments and different institutions and, within the state, each body seeks to have the resources necessary for doing its job well. We want to point to some areas where we have already advanced, areas that should be sources of encouragement for all of us.

One example is the success achieved by the Symphony Orchestra, which has been completely reorganized. Not only has it reached a high level in the artistic sense, but also in the revolutionary sense, for there are now 50 members of the Symphony Orchestra who belong to the militia.

The Cuban Ballet has also been rebuilt and has just made a tour abroad, where it won admiration and recognition in all the countries it visited.

The Modern Dance Group has also been quite successful, and has been highly praised in Europe.

The National Library, for its part, is working hard on behalf of culture. It is engaged in awakening the interest of the people in music and painting. It has set up an art department with the objective of making fine paintings known to the people. It has a music department, a young people’s department, and a children’s section.

Shortly before coming here, we visited the children’s department of the National Library. We saw the number of children who were there, the work that is being done there. The progress made by the National Library is a motivation for the government to provide it with the means necessary for continuing this work.

The National Printing House is now a reality, and with its new form of organization, it is also a victory for the revolution that will contribute mightily to the education of the people.

The Cuban Film Institute [ICAIC] is also a reality. The first stage has consisted chiefly in supplying it with necessary equipment and materials. The revolution has established at least the foundation of a film industry. This has required a great effort, if it is kept in mind that ours is not an industrialized country and that the acquisition of all this equipment has meant sacrifices. Any lack of facilities for the cinema is not due to a restrictive government policy, but simply to the scarcity of economic resources at present for creating a movement of film enthusiasts that would permit the development of all cinematic talent when the resources are available. For its part the Cuban Film Institute’s policy will be the object of discussion, and of emulation among the various work teams. It is not yet possible to assess the work of ICAIC itself. The film institute has not yet had time to do enough work to be judged, but it has been working hard, and we know that a number of its documentaries have contributed greatly to making the revolution known abroad. But what we should emphasize is that the foundation for the film industry has already been laid.

There has also been cultural work done in the form of publicity, lectures, and so on, sponsored by different agencies. However, this is nothing compared to what can be done and what the revolution aims to do.

There are still many questions to resolve that are of interest to writers and artists. There are problems of a material nature, in other words, of an economic order. Yesterday’s conditions do not exist now. Today there is no longer a small privileged class to buy the works of artists—although at miserable prices, to be sure, since more than one artist died in poverty and neglect. These problems remain to be confronted and solved, and the revolutionary government should solve them. The National Council of Culture should be concerned with them, too, as well as with the problem of artists who no longer produce and are left completely abandoned. Artists should be guaranteed not only adequate material conditions for the present, but security for the future. In a certain sense, now, with the reorganization of the Institute of Royalty Payments, the living conditions of a great number of authors, who were miserably exploited and whose rights were scorned, have improved considerably. Today, authors, many of whom used to live in extreme poverty, have incomes that permit them to escape from that situation.

These are steps that the revolution has taken; but they are only preliminary steps. They will be followed by other steps that will create still better conditions.

There is also the idea of organizing a place where artists and writers can rest and work. Once, when we were traveling throughout the whole national territory, the idea occurred to us in a very beautiful place, on the Isle of Pines, to build a community in the middle of a pine forest, where we could send prize-winning writers and artists (at that time we were thinking about establishing some sort of prize for the best progressive writers and artists of the world). That project did not materialize, but it can be revived and a place can be created in some peaceful haven that facilitates rest, that facilitates writing. I believe that it is worthwhile for artists, and architects as well, to begin thinking of and planning the ideal retreat for writers and artists, and to see if they can agree. The revolutionary government is ready to contribute its share to the budget, now that everything is planned.

Will such planning be a limitation imposed by us revolutionaries on the creative spirit? Don’t forget that we revolutionaries have been improvising a bit, and are now faced with the reality of planning. That presents a problem to us too, because until now we have had a creative spirit toward revolutionary initiatives and revolutionary investments, which are now part of a plan. So don’t think we are exempt from the problem, for we could protest too. In other words, now that we know what is going to be done next year, the following year, and the year after that, who is going to dispute the fact that economic planning is necessary? But the construction of a retreat for writers and artists fits in with that plan. Truly, it would be a source of satisfaction for the revolution to accomplish this project.

We have been concerned here with the present situation of writers and artists. We have overlooked future perspectives to some degree. And we, who have no reason to grumble about you, have also spent a moment thinking about the artists and writers of the future. We wondered what it would be like if the members of the government—not us necessarily—and the artists and the writers were to meet again, as they should, in the future, in five or 10 years, when culture has achieved the extraordinary development we hope it will achieve, when the first fruits of the present educational and training programs begin to appear.

Long before these questions were raised, the revolutionary government was already concerned about the extension of culture to the people. We have always been very optimistic. I believe that it is not possible to be a revolutionary without being an optimist, because the difficulties that a revolution has to surmount are very serious, and one has to be an optimist. A pessimist can never be a revolutionary.

The revolution has had various stages. There was a stage when different agencies took the initiative in the field of culture. Even INRA [National Institute of Agrarian Reform] was conducting activities of a cultural nature. There was even a clash with the National Theater, because certain work was being done there and suddenly we were off doing other work on our own. Now all that is within one organization.

In connection with our plans for the peasants in the cooperatives and state farms, the idea arose of extending culture into the countryside, to the state farms and cooperatives. How? By training music, dance and drama instructors. Only optimists can take initiatives like that. So how were we to awaken love for the theater, for example, among the peasants? Where were the instructors? Where would we get instructors to send to 3,000 state farms and 600 cooperatives, for example? All this presents difficulties, but I am certain that you will all agree that if this is achieved it will be a positive accomplishment. Above all, it will be a start in discovering talents among the people and transforming the people from participants into creators, for ultimately it is the people who are the great creators. We should not forget this, and neither should we forget the thousands and thousands of creative talents lost in our countryside and cities due to lack of conditions and lack of opportunity to develop. Many talents have been lost in our countryside—of that we are sure—unless we presume ourselves to be the most intelligent people ever born in this country, and I want to say that I presume no such thing.

I have often given as an example the fact that of several thousand children in the place where I was born, I was the only one who was able to study at the university—study poorly to be sure. And I first had to attend a number of schools run by priests, and so on. I don’t want to anathematize anyone, although I do want to say that I have the same right as anyone here to say what I please, to complain. I have the right to complain. Someone spoke of the fact that he was molded by bourgeois society. I can say that I was molded by something even worse, that I was molded by the worst reactionaries, and that a good many years of my life were lost in obscurantism, superstition and lies.

That was the time when you were not taught how to think, but forced to believe. I am of the opinion that when a human being’s ability to think and reason is impaired, that human being is transformed into a domesticated animal. I am not challenging anyone’s religious beliefs; we respect those beliefs, we respect the right to freedom of belief and religion. But they did not respect my right to this freedom. I had no freedom of belief or religion. On the contrary, they imposed a belief and a religion on me and domesticated me for 12 years.

Naturally I have to speak with an element of grievance about those years, the years when young people have the greatest interest and curiosity about everything, years I could have employed in systematic study that would have enabled me to acquire the culture that the children of Cuba today are going to have every opportunity to acquire.

With all that, only one in a thousand could get a university degree and that person had to bear that millstone where only by a miracle was his mind not crushed forever. The one person in a thousand had to go through all that. Why? Because he was the only one of a thousand who could afford to study at a private school. Now, am I to believe that I was the most capable and intelligent of the thousand? I believe that we are a product of selection, but not natural selection so much as social. I was selected to go to the university by a process of social selection, not natural selection. Who knows how many tens of thousands of young people, superior to us all, have been left in ignorance by social selection. That is the truth. And whoever thinks of themselves as an artist should remember that there are many people, better than they are, who were unable to become artists. If we do not admit this, we are avoiding reality. We are privileged, among other things, because our fathers were not wagon drivers. What I have said shows the enormous number of talented minds that have been lost simply through lack of opportunity.

We are going to bring opportunity to all those minds; we are going to create the conditions that permit all talent—artistic, literary, scientific or otherwise—to develop. Think about the significance of a revolution that permits such a thing. As of right now, we have already begun teaching everyone to read and write, and we will have accomplished this by the next school term. Add to this the creation of schools everywhere in Cuba, educational advancement campaigns, and the training of teachers, and we will be able to discover and bring to light every talent.

And this is only the beginning. All the teachers in the country will learn to recognize which child has a special talent, and will recommend which child should be given a scholarship to the National Academy of Art, and at the same time they will awaken artistic taste and love for culture among adults. Some trials have been made to demonstrate the capacity of peasants and common people to assimilate artistic questions, to assimilate culture and immediately begin to produce it. There are compañeros who have been at some cooperatives that now have their own theater groups. Recent performances in various parts of the republic, and the artistic works of ordinary men and women, demonstrate the interest of the people of the countryside in all these things. Imagine, then, what it will mean when we have drama, music and dance instructors at each cooperative and each state farm.

In the course of only two years, we will be able to send 1,000 instructors, from each one of these fields, more than 1,000 in drama, dance and music.

The schools have been organized. They are already functioning. Imagine when there will be 1,000 dance, music and drama groups throughout the island, in the countryside—we are not speaking of the city, it is somewhat easier in the city. Imagine what that will mean for cultural advancement, because some have spoken here of the need to raise the level of the people. But how? The revolutionary government is concerned about this question, and it is creating conditions so that within a few years the people’s level of culture will have been raised tremendously.

We have selected those three branches, but we can continue selecting other branches and we can continue working to develop all aspects of culture.

The school of art instructors is already functioning, and the compañeros who work there are satisfied with the progress of that group of future instructors. In addition, we have already begun to construct the National Academy of Art, separate from the National Academy of Manual Arts. Cuba is certainly going to have the most beautiful Academy of Art in the world. Why? Because that academy is going to be located in one of the most beautiful residential districts of the world, where the section of the bourgeoisie of Cuba living in the greatest luxury used to reside, in the best district of that section of the bourgeoisie that was the most ostentatious, the most luxurious, and the most uncultured—let me say this in passing, because none of those houses lacked a bar, but with few exceptions their inhabitants did not concern themselves with cultural questions. They lived in an incredibly luxurious manner, and it is worthwhile to take a trip there to see how these people lived. But they didn’t know that one day an extraordinary Academy of Art would be built there, and this is what will remain of what they built, because the students are going to live in their homes, the homes of millionaires. They will not live sheltered lives, they will live in a homelike atmosphere, and they will attend classes in the academy. The academy is going to be located in the middle of the Country Club district, and it will be designed by a group of architects and artists. They have already begun work, and they are committed to finishing by December. We already have 300,000 feet of mahogany. The schools of music, ballet, theater and plastic arts will be in the middle of a golf course, in a dreamlike setting. This is where the Academy of Art will be located, with 60 houses surrounding it, with a social center, dining rooms, lounges, swimming pools, and also a building for visitors, where the foreign teachers who are coming to assist us can live. This academy will have a capacity of up to 3,000 children, that is, 3,000 scholarship students. We expect it to start operating in the next school year.

The National Academy of Manual Arts will also begin functioning soon. It, too, has another group of houses for students to live in, another golf course, and a type of construction similar to the others. These academies will be national in character. This does not mean in any way that they are the only schools, but that the young people who show the greatest ability will receive scholarships to go there, costing their families absolutely nothing. These youth and children are going to have ideal conditions for developing their abilities. Anybody would want to be a child now, to attend one of those academies. Isn’t that so? We spoke here of painters who used to live off café con leche alone. Just imagine how different conditions will be now, and we will see if the ideal conditions for developing the creative spirit are not found. Instruction, housing, food, general education… There will be children who will begin to study in those schools at the age of eight, and along with artistic training, they will receive a general education. They will be able to fully develop their talents and their personalities.

These are more than ideas or dreams; these are the realities of the revolution. The instructors are being trained, the national schools are being organized, the schools for art appreciation are also being founded. This is what the revolution means. This is why the revolution is important for culture. How could we do this without a revolution? Let’s suppose that we are afraid that “our creative spirit is going to whither or be crushed by the despotic hands of the Stalinist revolution.”

Wouldn’t it be better, ladies and gentlemen, to think about the future? Are we going to think about our flowers withering when we are planting flowers everywhere? When we are forging those creative spirits of the future? Who would not exchange the present, who would not exchange even their own present existence for that future? Who would not exchange what they have now? Who would not sacrifice what they have now for that future?

Doesn’t someone with artistic sensibility also possess the spirit of the fighter who dies in battle, understanding that they are dying, that they are ceasing to exist physically, in order to enrich with their blood the triumph of their fellow beings, of their people? Think about the combatant who dies fighting, who sacrifices everything: life, family, wife, children. Why? So that we can do all these things. And what person with human sensibility, artistic sensibility, does not think that to do all that the sacrifice must be worthwhile? But the revolution is not asking sacrifices from those with creative genius; on the contrary, it says: Put that creative spirit at the service of the revolution, without fear that your work will be impaired. But if, some day, you think that your personal work may be impaired, then say: It is well worth it for my work to be impaired if it contributes to the great work before us.

We ask artists to develop their creative efforts to the fullest. We want to bring about the ideal conditions for artists and intellectuals to create, because if we are creating for the future, how can we not want the best for the artists and intellectuals of today? We are asking for maximum development on behalf of culture and, to be very precise, on behalf of the revolution, because the revolution means precisely more culture and more art.

We ask intellectuals and artists to do their share in the work that is, after all, the work of this generation. The coming generation will be better than ours, but we will be the ones who will have made that better generation possible. We will be the ones to shape that future generation. We, the members of this generation, whether young or old, beardless or bearded, with an abundant head of hair, or no hair, or with white hair. This is the work of us all. We are going to wage a war against ignorance. We are going to wage a great battle against ignorance. We are going to unleash a merciless fight against ignorance, and we are going to test our weapons.

Is there anyone who doesn’t want to collaborate? What greater punishment is there than to deprive oneself of the satisfaction that others are getting? We spoke of the fact that we were privileged. We learned to read and write in a primary school, went to secondary school, to university, to acquire at least the rudiments of education, enough to enable us to do something. Shouldn’t we consider ourselves privileged to be living in the midst of a revolution? Haven’t we read about other revolutions with great interest. Who has not avidly read the histories of the French revolution, of the Russian revolution? Who has never dreamed of witnessing those revolutions personally? In my own case, for example, when I read about the Cuban War of Independence, I regretted that I had not been born in that period and that I had not been a fighter for independence and had not lived through that epic time. All of us have read the chronicles of our War of Independence with deep-felt emotion, and we envied the intellectuals and artists and fighters and leaders of that time.

However, we have the privilege of living now and being eyewitnesses to a genuine revolution, to a revolution whose strength is now developing beyond the borders of our country, whose political and moral influence is making imperialism on this continent tremble and stagger. The Cuban revolution has become the most important event of this century for Latin America, the most important event since the wars of independence of the 19th century. In truth, the redemption of humanity is something new, for what were those wars of independence but the replacement of colonial domination by the domination of ruling and exploiting classes in all those countries?

It has fallen to us to live during a great, historic event. It can be said that this is the second great, historic event that has occurred in the last three centuries in Latin America. And we Cubans are active participants, knowing that the more we work, the more the revolution will become an inextinguishable flame, the more it will be called upon to play a transcendental role in history. You writers and artists have had the privilege of being living witnesses to this revolution. And a revolution is such an important event in human history that it is well worth living through, if only as a witness. That, too, is a privilege.

Therefore, those who are incapable of understanding these things, those who let themselves be tricked, let themselves be confused, those who let themselves become perplexed by lies, are renouncing the revolution. What can we say about those who have renounced it? How can we think of them but with sorrow? They have abandoned this country, in full revolutionary effervescence, to crawl into the belly of the imperialist monster, where no expression of the spirit can have any life. They have abandoned the revolution to go there. They have preferred to be fugitives and deserters from their homeland rather than remain here even if only as spectators.

You have the opportunity to be more than spectators, you can be actors in the revolution, writing about it, expressing yourselves about it. And the generations to come, what will they ask of you? You might produce magnificent artistic works from a technical point of view, but if you were to tell someone from the future generation, 100 years from now, that a writer, an intellectual, lived in the era of the revolution and did not write about the revolution, and was not a part of the revolution, it would be difficult for a person in the future to understand this. In the years to come there will be so many people who will want to paint about the revolution, to write about the revolution, to express themselves on the revolution, compiling data and information in order to know what it was like, what happened, how we used to live.

I recently had the experience of meeting an old woman, 106 years old, who had just learned to read and write, and I proposed to her that she write a book. She had been a slave, and I wanted to know what the world looked like to her as a slave, what her first impressions were of her life, of her masters, of her fellow slaves. I believe that this old woman could write something more interesting than any of us could about that era. It is possible that in a single year someone can learn to read and write, and then write a book, at 106 years of age. That’s what happens in a revolution! Who can write about what a slave endured better than she can?

And who can write about the present better than you? How many people who have not lived through the present will begin to write in the future, at a distance, selecting material from other writings?

On the other hand, let us not hasten to judge our work, since we will have more than enough judges. What we have to fear is not some imaginary, authoritarian judge, a cultural executioner. Other judges far more severe should be feared: the judges of posterity, of the generations to come. When all is said and done, they will be the ones to have the last word!

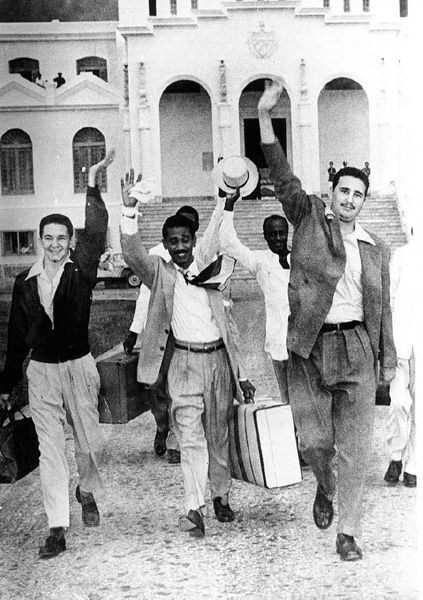

Raúl Castro, Juan Almeida and Fidel Castro leaving prison, May 15, 1955. Behind them is Armando Mestre. Imprisoned after the July 26, 1953, assault on the Moncada military garrison, Fidel Castro was released in 1955 as the result of a popular amnesty campaign.

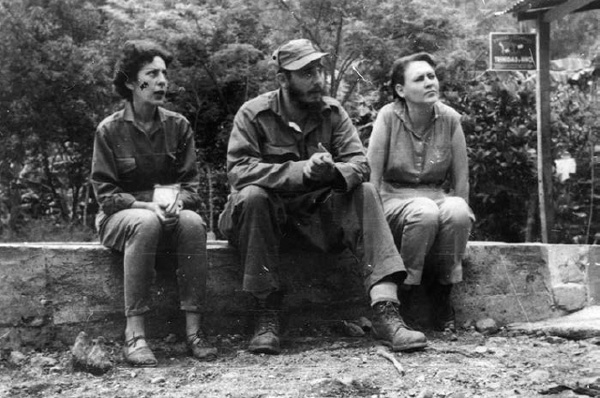

Celia Sánchez, Fidel Castro and Haydée Santamaría in the Sierra Maestra (1956–58).

Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra during the Cuban revolutionary war (1956–58).

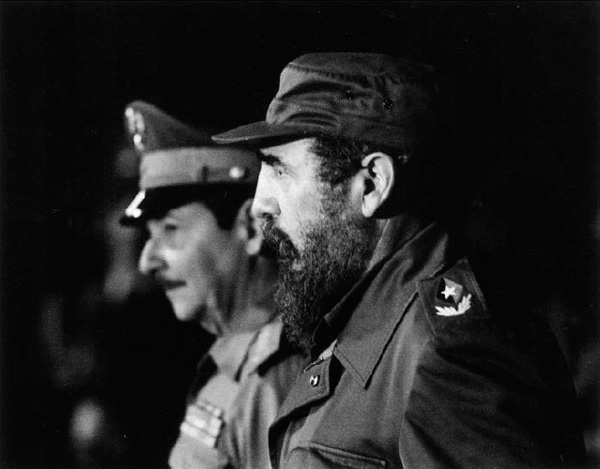

Fidel Castro during the Cuban revolutionary war (1956–58).

Sierra Maestra, 1957: Che Guevara (second from left), Fidel Castro (fourth from left, standing), Raúl Castro (kneeling, front), and Juan Almeida (f rst on the right).

Fidel Castro speaking at Camp Columbia, Havana, January 8, 1959. Camilo Cienfuegos is on Fidel’s right.

Camilo Cienfuegos and Fidel Castro, January 1959. Photograph by Alberto Korda.

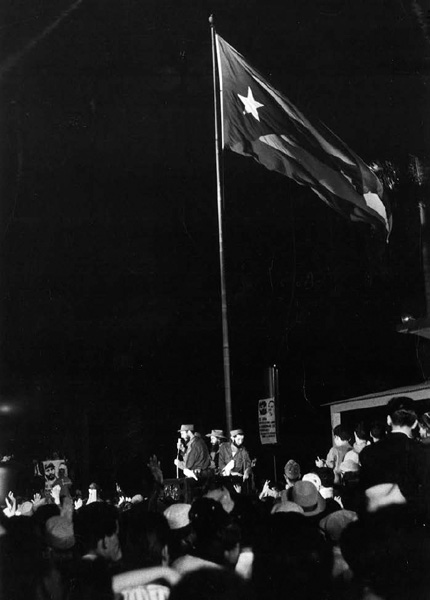

Fidel Castro addressing a rally in front of the presidential palace in Havana, January 21, 1959.

Havana, January 1959.

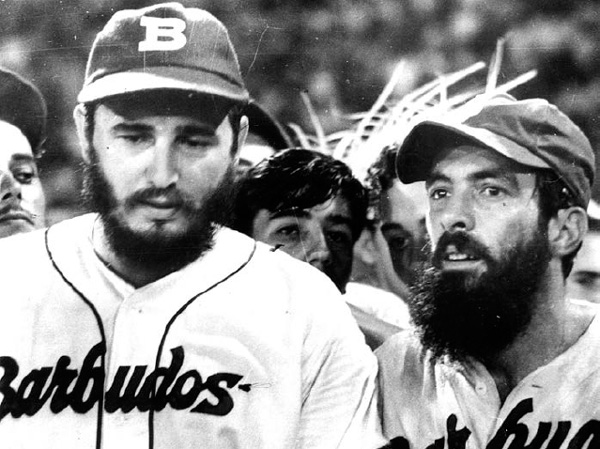

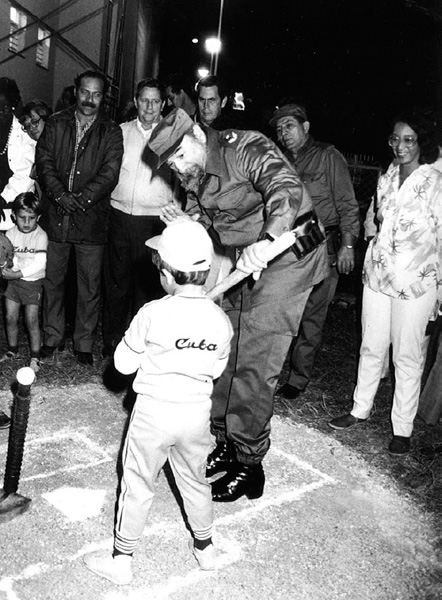

Havana, January 1959. Fidel Castro and Camilo Cienfuegos playing baseball for the “Barbudos” (The Bearded Ones).

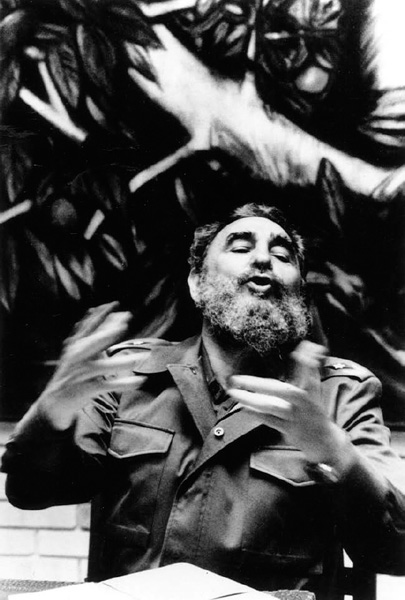

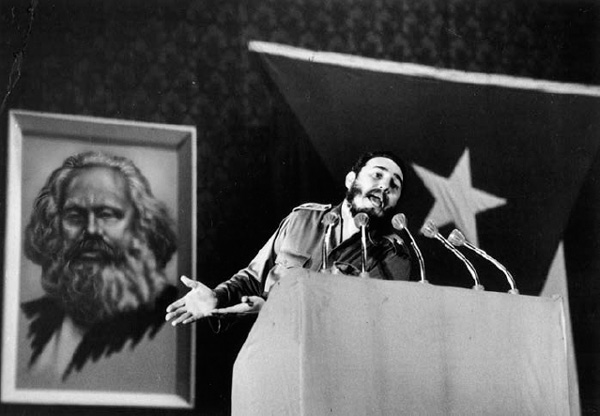

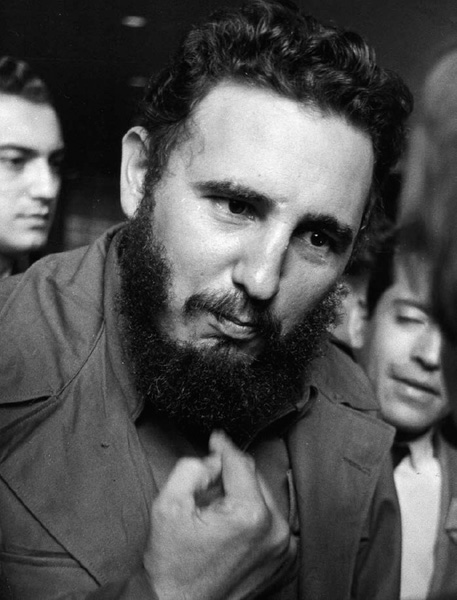

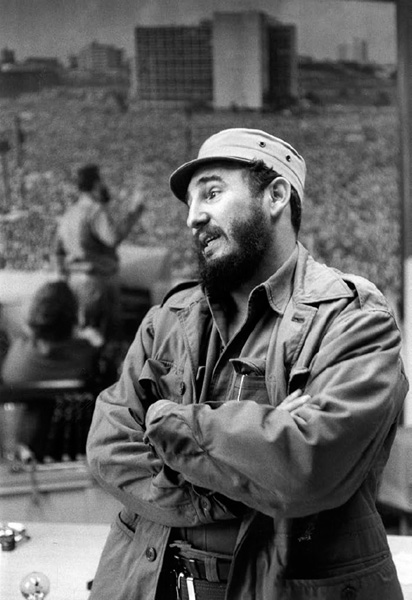

Fidel Castro, 1960s.

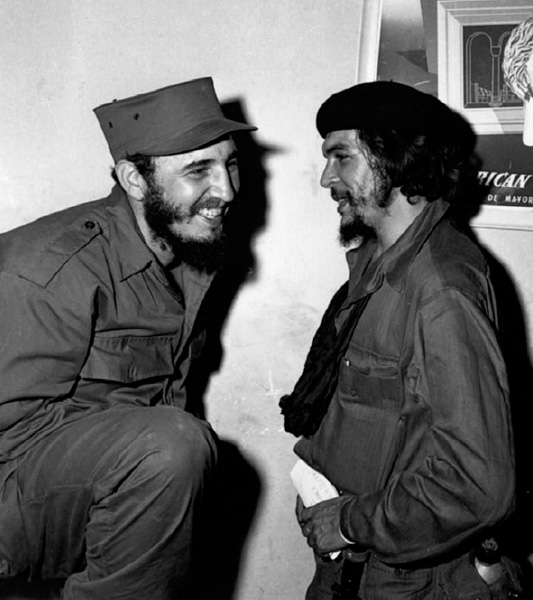

Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, January 1959.

Drafting the agrarian reform law, 1959. Photograph by Alberto Korda.

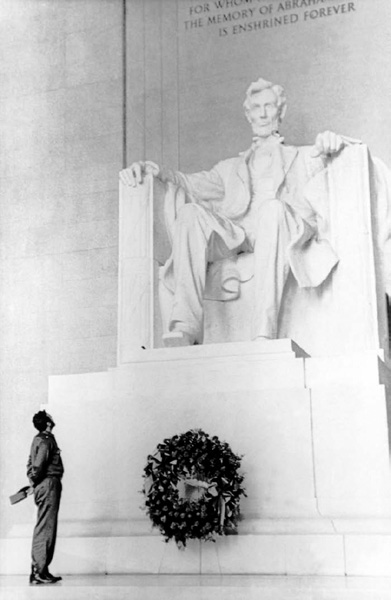

Fidel Castro in Washington, DC, April 1959. Photograph by Alberto Korda.

Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs, April 1961.

Fidel Castro during voluntary work.

Fidel Castro doing voluntary work in the sugarcane f elds.

Fidel Castro and Che Guevara at a rally.

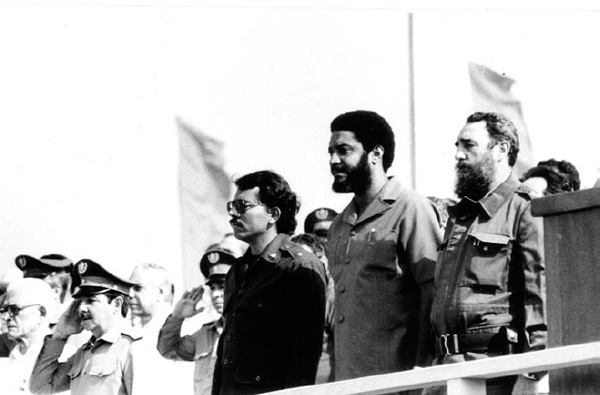

Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, Maurice Bishop of Grenada and Fidel Castro, May 1, 1980, Havana.

Nelson Mandela and Fidel Castro, July 26, 1991, Cuba.

Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro.

Raúl Castro and Fidel Castro.