3 |

It’s the Outcome! |

EVERY YEAR PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS(PWC) PUBLISHES A global CEO survey. In the 2013 edition, 1,330 CEOs gave views on their company’s business challenges and prospects for growth. It was an intriguing read. With some facts now on the table about the accuracy of their predictions, it is even more intriguing.

Of CEOs, 80% expected the global economy to stay the same or to decline in 2013. But interestingly, 81% of them were confident in their own growth prospects. At first, that seems like a dichotomy. But then, what else would you have expected? A CEO who is not confident in his or her ability to grow a company—almost regardless of economic conditions—probably should not be its CEO, right? The results for technology company CEOs were no different from the overall group: 76% of them expected the global economy to stay the same or decline while 84% believed their company would grow in the ensuing year.

That’s not quite what is happening.

At TSIA we track the financial performance of 50 of the world’s largest technology service providers in an index we call the Service 50. As you might guess, the vast majority of those large service organizations are embedded within technology product companies such as IBM, SAP, ABB, Fujitsu, and Cisco. In fact, product companies act as host to 8 of the top 10 and 72% of the 50 service organizations. So we closely study their product results, not just their services. The balance of the index is made up of “pure services” companies such as Accenture and Wipro. We think the Service 50 index is a great proxy for the tech industry overall because it nicely reflects the blend of business customer tech spending across both products and services.

The Service 50 data suggests that some tech CEOs may have been a bit too optimistic. In reality, of the large global tech companies we track, 56% began 2013 with revenues that stayed flat or shrank from the same quarter the previous year.1 That is pretty shocking, especially because that trend has been fairly consistent recently. When you look a level deeper, the shock waves get a bit bigger. The vaunted product businesses within these global hardware and software brands took it especially hard—a surprising 66% of them had flat or declining product revenue growth in the first quarter of 2013 compared to the same quarter of 2012. The idea that the famously high-growth, high-tech leaders, as a group, saw their combined revenues shrink 4% is chilling. It would have been worse had not 68% of them been able to grow their services revenue. The continued shift in revenue mix from products to traditional services—a shift that many tech companies don’t want to publicly highlight—actually helped mitigate what could have been a much tougher story.

The declining economics of the tech products business is not just a matter of revenue. There is also a margin problem. Hardware margins continue to decline almost everywhere. At the same time, sales costs are rising for many reasons. Even large software companies in the B2B world are struggling to make a profit building and selling new products. Of the 16 software companies in the TSIA Service 50, half had flat or declining product businesses. As a group, product revenue for the 16 bellwether software brands in the Service 50 shrank 2%. But, like the hardware crowd, 12 were aided on the top line by growing service businesses. As a group, service revenue grew an astonishing 18%.

We don’t write press releases on these sobering figures, but the truth is that many companies in the B2B tech industry are struggling just to stay flat. It can’t be blamed on the global economy. The world gross domestic product (GDP) for 2013 is predicted to increase 3%.2 That means that the growth of the combined Service 50 companies could lag the overall global economy by 7%!

What’s more, we fear further bad news is around the corner. We are predicting that the masking effect provided by growing service revenues is not sustainable. We think it’s a false positive. The huge majority of these service revenues are what we refer to as “product-attached services”: things such as installation and implementation services, customer support, maintenance, and education. For years, supplier service executives were told that they did not need to worry about business strategy because they were safely inside product companies. All the company needed was a good product strategy. Their strong product sales would then pull the services revenue. Except now the product business at many B2B suppliers is shrinking. It is only a matter of time before it pulls the product-attached service business right down with it. That is already starting to happen at some of the biggest tech brands in B2B, and our math suggests it could become widespread within the next few years. When it does, there are going to be many sad faces in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street.

While the facts of recent performance do not seem to have dampened the bullishness of tech CEOs, there is some weakening of the grip. According to the PWC Global CEO Surveys, in 2011, 54% were very confident in their annual growth prospects. In 2012, it dropped to 37%; in 2013, to 34%. So the anemic real growth rates at many large tech companies may finally be having an effect on their optimism. We think it’s a lot more than just a temporary lull. We think that something pretty fundamental is going on.

Market Maturity

We assert that the old engines on the growth train are running out of steam for many B2B tech suppliers. Although remaining publicly optimistic, many high-tech and near-tech CEOs we talk to sense something is awry. And it is not just the large company CEOs. We have given speeches all over the world since Consumption Economics3 was published, not just to B2B OEMs but also often to their resellers in the channel. They, too, sense that the tech industry is diverging from normal market conditions. Something is definitely amiss.

We think what is amiss has a name, an evil name. It’s called market maturity. The consumption gap has finally caught up with an industry that has not had a real revolution in a long time. The “excess capacity” and “good-enough tech” phenomena have fundamentally changed many business customers’ buying habits. The appetite for technology asset refresh has slowed in developed countries. Although emerging markets do offer top-line growth, it is growth at the low-end, low-margin range of the product line. Often it is in countries where customers loathe paying for services. Many CEOs privately acknowledge that this won’t be enough to carry the day.

Although many in the high-tech arena are busy hyping the cloud right now, the real truth is that the net impact of the cloud will ultimately reduce the amount of hardware, software, and equipment that the business customer has on-site, not increase it. Even when the physical devices are on the customer’s premises, such as industrial equipment, the “smarts” will often be in the cloud. High-tech business customers will likely own far fewer assets in far fewer data centers. IT departments or operations staffs will likely be smaller, not bigger. Fewer assets will be customer-owned; more will be supplier-owned and sold on a pay-as-you-go model.

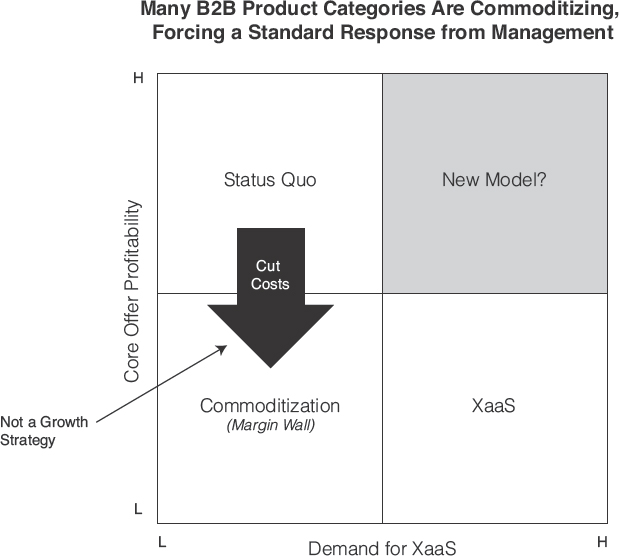

These trends are going to make real growth difficult to come by using traditional approaches. So it’s hard to understand why, even in the face of these weak growth numbers and disruptive trends, the tactics that many supplier CEOs plan to utilize to restore growth look so traditional (see Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 Top Priorities in Customer Growth and Investing

Everyone is planning to peddle harder—companies are hiring more salespeople, bringing out new products, and trying to adjust pricing schemes, but they can’t keep up. It’s not that the current operating models of most B2B tech companies are wrong; they just aren’t aging well. The collective strategy totem pole at work on the growth problem still seems dominated by the same influences. It’s logical to keep doing what had once made your company successful. Suppliers have become used to being in a hot technology market in which each new release puts them back into product-driven hyper-growth. But once the market matures, that play just doesn’t work as well anymore. The “more sales reps + more products” engine is suffering major efficiency problems these days. Tech CEOs may be forced to change their game plan. Indeed, 54% of CEOs who responded to the PwC survey said that they are exploring new business models.

But What New Business Model?

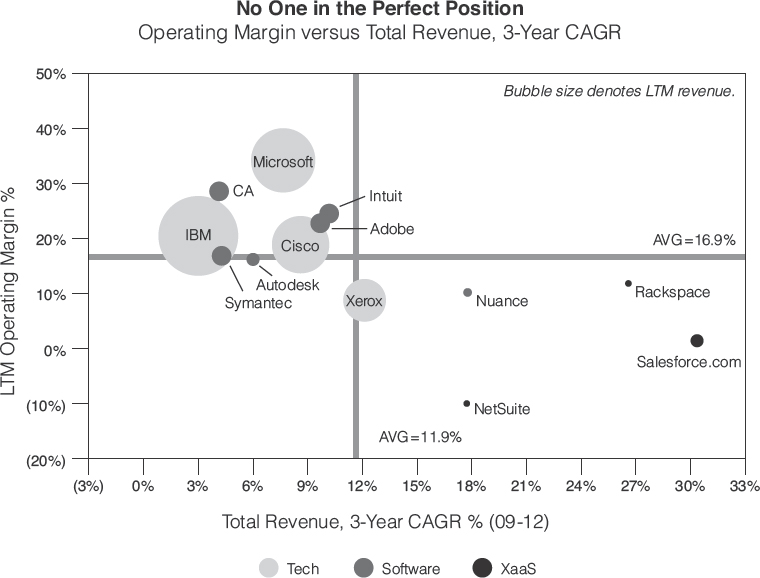

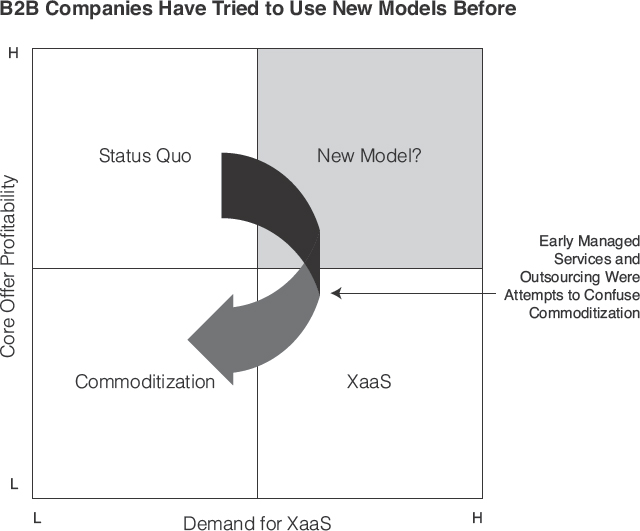

That is the key question, the one turning the collective strategy brains at most B2B high-tech and near-tech companies inside out. We have been in the midst of this conversation so many times at so many companies; we think we can boil the quest down to a journey across a simple 2 × 2 matrix, as shown in Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2 But What Is This New Model for B2B?

Every supplier starts in the upper-left quadrant: business as usual. This means continuing to run the current operating model—probably the one that built the company, the one that the executives understand, that Wall Street knows how to value, that engineers know how to build, and that sales knows how to sell. Frankly, if that model were still a viable growth option, we would not be writing this book and suppliers would not be reading it. Two macro-market trends are now tempting many high-tech and near-tech product companies to move off that square—to uncomfortably venture out of their comfort zone.

The first trend is growing evidence of deteriorating core-offer profitability. This is what we have highlighted in this chapter: flattening growth, declining margins, increasing sales costs, and traditional service revenues reaching their apex. A couple of years ago, it was easy to blame this on “adverse market conditions,” but that excuse is wearing thin. Overall economic growth exceeding the growth of many tech companies is a wake-up call.

The second macro-trend is rapidly growing interest among customers to purchase technology via an “X-as-a-service” model. There are many symptoms of this trend that traditional high-tech suppliers can see and feel. They could be as obvious as XaaS companies that are emerging as competitive threats in new business deals. Or it could be that business buyers are trumping technical buyers in the decision-making process more often. Especially with true cloud architectures, the technical buyers are losing some of their influence. All these are indications of a technology consumption and pricing model that is truly changing. When you can buy jet engines by the hour, computing power by the minute, and computed tomography (CT) brain scans by the image, you know there is demand for XaaS.

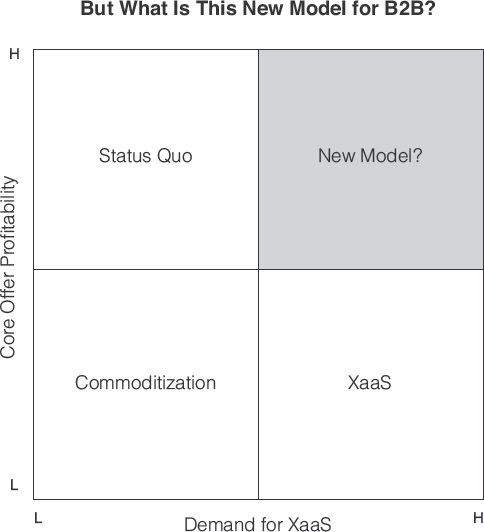

This brings us to the question of action. Assuming you are a supplier who is sensing a bit of either commoditization or demand for XaaS (or both), what do you do? That is what the rest of this book is about. Let’s start that journey back at our 2 × 2 matrix (see Figure 3.2). The ugliest destination is clearly commoditization. In Consumption Economics we talked about what happens at supplier companies when products—even entire product categories—hit (what we termed) the “Margin Wall.”4 The Margin Wall is that horrible place where the cost of developing, manufacturing, and selling a product exceeds the price of the product. Crashing into that wall is no fun for management. It means that there is not enough value in a product—either organically or competitively—to support a profitable selling price. If you don’t have some profitable downstream offer such as supplies or services, volume won’t help. When whole categories hit the Margin Wall—such as servers or multi-function printers (MFPs)—even bringing out new products with new features or lower prices won’t usually do the trick. Although they may bring you a few months of profitability, competition quickly catches up, price competition takes over, and the Margin Wall is soon back in full view.

Commoditization is well known in hardware industries, but as we have contended (based on our definition, which includes the cost of manufacturing as well as developing and selling the product), there are growing numbers of software and software-intensive products that qualify. When a supplier’s core offer(s) reach that point, management’s options are limited.

Executives at these companies are not let off the hook by investors just because they have one or more major product lines crashing into the Margin Wall. They are still expected to grow and generate increasing profits. The growth requirement is often met through increased unit volumes obtained by using price (or low-end products) to capture market share. The increased profits come mainly from cutting costs. So although they wait and hope for another hit product, those in management jump from innovation to cost-reduction as they try to outrun the ugly monster. They spend all their customer face time talking about their commitment to R&D and more of their internal time figuring out what jobs they can eliminate. They know that is not going to be fun. They know it is not a sign of success. And they know that cutting costs is not a real business strategy. So, naturally, suppliers go to great lengths to avoid moving in a straight line from the upper-left quadrant to the lower-left one, as shown in Figure 3.3.

There have been some interesting efforts to avoid that awful path. One of the favorite B2B supplier tactics over the last couple of decades has been to take the commoditized products, mix them with labor, and bring them to market together as a service. Let’s take a quick look at an important case study—one in which leading suppliers in one of the oldest and most mature segments of tech made an effort to “fake out” the Margin Wall.

The Lessons of Outsourcing and Early Managed Services

The copier/printer business is huge and has been for decades. In the glory days of the 1980s and 1990s there were literally dozens of major manufacturers all around the world who were high-growth, high-profit, product-driven tech companies. Not only were the manufacturers profitable but so were their networks of dealers. It was good to be a supplier of office equipment to business customers. Then crash! … into the Margin Wall they went. First went the products themselves: Competition was vast, customers were only using the basic capabilities of the products, desktop printers were becoming more capable, and prices began to fall. Although not fun, it was survivable. There were still very lucrative aftermarket revenue streams of supplies and service. Toner, paper, and maintenance contracts became the perennial “blades” for the copier/printer “razor.” But eventually even that was not enough to maintain the growth and profits demanded by shareholders. So what did many of the market leaders do? They not only provided the devices to their large customers but also offered to supply the labor to optimize and operate them. In one of the earliest, most widespread efforts to outwit commoditization, these suppliers married product with outsourcing. Some called it “outsourcing,” whereas others called it “managed services.” The basic ones simply offered to take over the job of keeping paper in the trays and toner cartridges full. Why should the customer’s employees have to waste their valuable time doing such a thing when the supplier can do it for them using low-priced labor? Other offers aimed squarely at the consumption gap. Suppliers offered to provide staff to operate the customer’s in-house copy centers. The value proposition was that the supplier could provide “factory-trained” experts who could operate the sophisticated equipment faster, better, and more efficiently than could the customer’s employees. The best suppliers endeavored to study and analyze both the print needs and the print practices of business customers in order to optimize them. Often this analysis could save the customer large amounts of money by optimizing when, where, and on what device documents were produced. Suppliers’ logic of marrying labor to the products was that they could sell an outsourcing contract, maybe make a little money on the labor, but far more importantly, the labor “wrapper” would allow them to pull through their product, supplies, and maintenance services at a higher margin. In effect, they used the outsourcing of management or operations to get control of a larger piece of the customer’s copy and print spending.

Why is this example so important? Because, although it worked for a period, companies using it ultimately failed to outwit the commoditization monster (see Figure 3.4).

FIGURE 3.4 New Models Tried by B2B Companies

Two things went wrong that offer valuable lessons for tomorrow’s successful suppliers. The first was that some suppliers did not focus hard enough on the labor component. They did not innovate ways to eliminate it, and they sometimes allowed themselves to be dragged far out of the domain of their expertise. Because they were either chasing revenue or felt they would lose the print business if they didn’t agree, office equipment suppliers started to become office labor suppliers. There were large contracts in which these product companies not only operated their equipment but also ran the mail and drove employee shuttle buses. They allowed themselves to be dragged into areas in which they had no real value, offered no real differentiation, and could capture no real margins. These suppliers were forced far out of their business model and ended up undertaking activities that made no real sense. They ended up adding labor rather than eliminating it.

The second harsh lesson was about pricing in the XaaS world. These managed service contracts were often quite large and complex. They included lots of different devices and software, some in very high quantities. They involved the supplies, often even the paper. They covered the services to install and maintain them and, of course, the labor to operate them. Somewhere along the way, one of the suppliers had a brilliant idea: Let’s simplify all this complexity and at the same time take all the risk out of the deal for the customer. How? By taking a multimillion-dollar deal and reducing it to a price per page. It was another first for the industry. Office equipment companies were among the early pioneers of taking large, complex technology solutions and offering them via a true consumption-pricing model. Sure, there was mainframe computing sold by the time slice before this. And there was outsourcing before this. But this was the whole enchilada: the products, the services, the supplies, and the operating labor—at 4 cents per page. The hope was that this approach would not only help simplify things for the customer; it would also be another tool to fake out commoditization. Before per-page pricing, the customer could tell exactly what they were paying for every component in the contract. What were they paying for this device here and for that one over there? How much was the paper? How much was the installation? Armed with that level of pricing, they could pit one potential supplier’s bid against all the others at the component level: “Well, your bid is OK on this part, but you need to get a lot more competitive on this other part,” they would say. Armed with that visibility, the customer could easily negotiate nearly all the margins out of the whole deal. By bundling it and pricing it by the page, the customer could not see what the component prices were. Early contracts on this pricing model were often very lucrative for the supplier. They applied a data and analytics approach to complex requests for proposals (RFPs) and came up with a pricing model that some competitors were afraid of or took too long to match. It seemed like a brilliant move. They won business and (sometimes) enjoyed solid margins—often much higher than if they had sold just the products alone. It seemed as though they had found a way to successfully confuse the monster.

Until later, that is. You see, by the time those early contracts came up for renegotiation a few years later, the other competitors were no longer afraid of per-page pricing. They too had their big data and analysis spreadsheets. They too could offer the simplicity the customer craved. Not only could they do it, they would do it at 3.8 cents per page.

Well, you can guess what happened next: 3.8 cents became 3.7 cents, which became 3.6 cents. And 15 years later, the price competition hasn’t taken a single day off. An early attempt to confuse commoditization actually ended up accelerating it. Because they had not innovated methods to reduce labor or to disengage from the low-value parts while retaining the high-value ones, the gross margins often went down with each successive renegotiation. By bundling a complex solution into a simple, XaaS pricing model these suppliers accidentally drove the entire category down. Consolidation hasn’t saved them, offshore manufacturing hasn’t saved them, and color hasn’t saved them. Today, there is not much money being made by the big office product manufacturers in the business of office products.

The takeaways are clear: First, new models that depend on applying labor to rescue a deteriorating product line are risky business. Second, beware the simple service price list. As far as we can see, every tech category that has adopted this approach has seen a race to the bottom ensue. We would strongly caution against a supplier viewing the switch to a subscription or other consumption-based pricing approach as their “new model.” First of all, it’s not a new model; it’s just a pricing tactic. Second, it is a dangerous one. If they bring the same old supplier operating model and just charge differently for it, they too could face a race to the bottom.

Is XaaS Really the New Model We Seek?

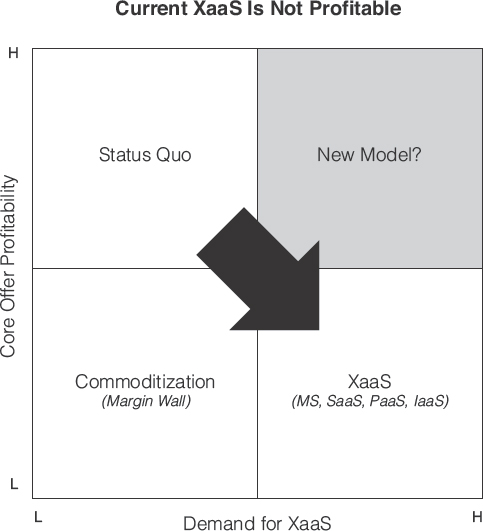

This brings us to the lower-right quadrant. Here we take up the hot B2B debate about the new model du jour—a debate that is raging in the collective strategy brains at many high-tech and near-tech suppliers as well as millions of business customers around the world. The new model du jour is, of course, cloud-enabled XaaS offers. You might call them SaaS; you might call them infrastructure as a service (IaaS) or platform as a service (PaaS). You might call them remote managed services (MS).

That cloud-enabled XaaS is considered the “new model” du jour in high-tech is undeniable. Pick up any business newspaper. Read the tech ads and articles. If they have to do with technology these days, it usually has to do with the cloud. Then insert yourself into an executive meeting at a major tech company. If the members of the executive teams aren’t talking cost cutting, they are talking about the cloud, specifically XaaS. Last, grab a seat on your next plane flight right next to a friendly CIO. Should he or she go to the cloud? Shouldn’t he or she go to the cloud? Where? When? Why? With whom? Yes, the cloud is big, it’s cool, and it’s here to stay. There is only one slight problem.

So far, the B2B cloud is unprofitable (see Figure 3.5).

FIGURE 3.5 Current XaaS Is Not Profitable

Technology suppliers, especially those who are feeling the tugs of eroding profitability or slowing growth in their core offers, have to find the explosive growth rates of new XaaS companies such as salesforce.com or AWS awfully compelling. Add to that the increasing customer demand for service-based pricing, assetless technology, or a less complex ownership experience, and you might wonder why every tech supplier has not moved with great haste from the upper-left to the lower-right quadrant of Figure 3.5. A few have but most have not. Why not? Because they can’t.

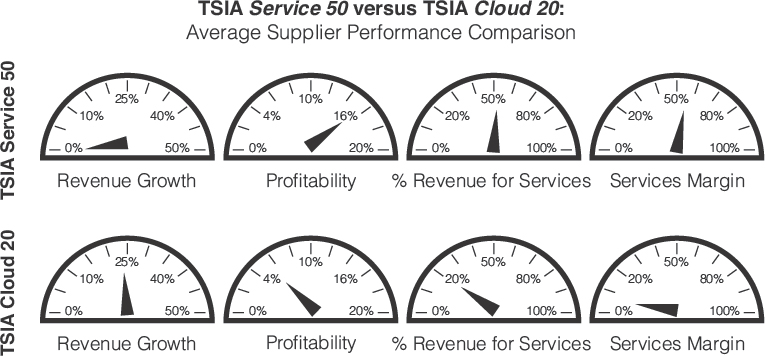

You have already seen some data from the TSIA Service 50. Let us now introduce you to another TSIA tracker we call the TSIA Cloud 20. Whereas Service 50 tracks the largest tech service suppliers, Cloud 20 tracks many of the largest, most successful XaaS companies. Earlier this year, we debuted a simple chart that compares the average financial performance of companies in the two indexes, shown in Figure 3.6.

FIGURE 3.6 Average Supplier Performance Comparison: TSIA Service 50 versus TSIA Cloud 20

First, look at the revenue growth of the large, traditional tech leaders that make up the Service 50. As we have already discussed, there isn’t any. Then contrast that revenue growth with the average growth rate of the companies that make up the Cloud 20. Get the picture? Now, look at the profitability comparison. The traditional tech suppliers are still very, very profitable. The profits are under pressure to be sure, and the tactics they are forced to use to deliver those profits are not their preferred ones. But the fact remains: These are profitable companies. Now contrast that with the average profitability of the Cloud 20 companies at around 4%. That is 75% lower. And there is something behind this data that you can’t see. If you tallied just the pure-play B2B XaaS companies, that average profitability drops precipitously. The fact is that of the 20 companies in the index, 11 are unprofitable or barely breakeven. The list of unprofitable B2B SaaS companies includes many of the big brands of the cloud such as salesforce.com, Workday, and NetSuite. Swapping a high-margin business for a breakeven business does not make a lot of sense to investors so far. As traditional tech companies think more deeply about their business model shift, it is not making a lot of sense to them either.

There are two other interesting dials on the dashboard. As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, the revenue and profits from the service businesses at many high-tech and near-tech product companies are the tide keeping the boat afloat at an acceptable level. You get another view of that by looking at the high percentage of total revenue that comes from services among these traditional tech leaders and the high gross margins associated with those offers. Without those contributions, the financial picture looks more than a bit darker. Now contrast that with the XaaS companies. As a group, they look almost like a service-free zone! The percentage of revenue coming from traditional service activities at the average Cloud 20 company is far less than half that of their traditional counterparts. And rather than being highly profitable, it is a breakeven business.

Is it that there are no services required in the cloud? Generally speaking, no. There are still implementations, integrations, and customer support activities in XaaS offers. In many cases, there may be fewer of them, but not few enough to explain this. So why then? It’s because the Cloud 20 consists of growth companies in land-grab mode. They value new contracts more than profits right now. They love to sell against companies that require expensive maintenance contracts, so many bundle customer support into the basic offer subscription price. Customers who twist these XaaS suppliers’ arms to get services such as implementation or training thrown into the contract at the last minute are often successful. The XaaS executives are confident the profits will be there mañana. For right now, they prioritize the booking.

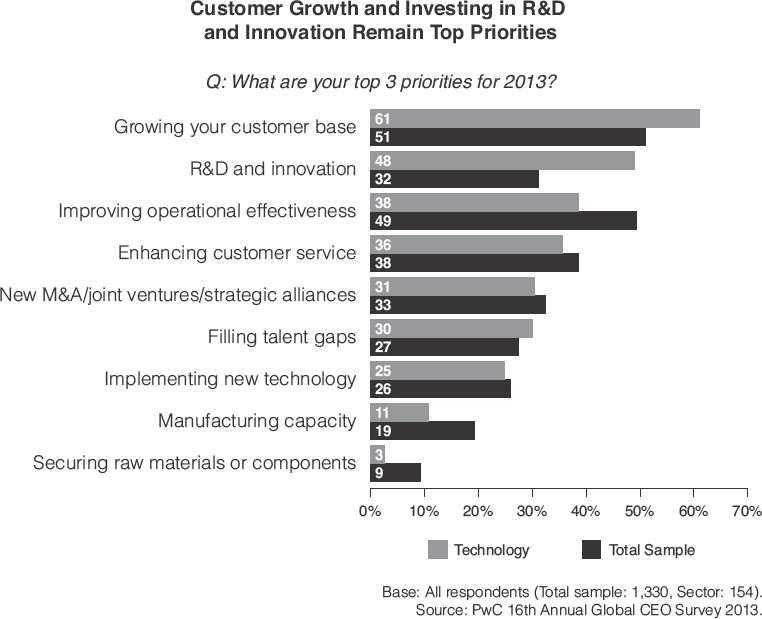

In Chapter 2, we asserted that Marc Benioff and Jeff Bezos probably believe that they could be highly profitable now if they needed to. We are almost certain they believe in mañana profits. But what we hear from the traditional high-tech companies that zero in on salesforce.com as the poster child of unprofitability is that Mr. Benioff claimed strong profits were right around the corner—and has been making that same claim for years. But it hasn’t happened. It’s not just Benioff and Bezos; it’s nearly everyone in this business model. Sure Oracle paid billions for Taleo, and SAP did the same for SuccessFactors. Both acquisitions were high growth, but neither was profitable. Look at the analysis shown in Figure 3.7, which compares growth and operating margins for many of the big names in both traditional and XaaS B2B business models over the three years from 2009 through 2012.

In this figure,5 the size of the circle indicates the size of the company. You can see the big IBM circle and the much smaller Rackspace one, for example. As a collective group of companies, the average three-year CAGR (compound annual growth rate) was 12.3%, and the average operating margin was 16.9% (these averages are represented by the perpendicular lines in the middle of the chart). But just as in our TSIA indexes, two things jump out at you. The first is that all the companies that were growing faster than the average (the lower-right quadrant) are XaaS models except Nuance. The second is that all the companies that were more profitable than the average (the upper-left quadrant) were traditional, on-prem suppliers during this period.

But the big, startling, frustrating revelation for suppliers in both camps is this: No one was above average in both (the upper-right quadrant). Of the companies we looked at, there is not a single B2B tech supplier that was both high growth and high profit. Not one.

So if you were the CEO of Microsoft, could you really go to Wall Street and tell people that you are moving to the lower right? That you were prepared to trade off profits for growth? That would be a tough investor briefing. Even just making a simple pricing change from up-front license to ongoing subscription has proved to be a tough road. Symantec, Adobe, Autodesk, and Intuit have all begun the move—four traditional B2B software companies courageous enough to begin their move off the Status Quo quadrant in our 2 × 2 matrix toward the XaaS one. All four have experienced bumps on the road to satisfying investors because of the lower up-front revenue of the subscription model and/or lower profitability compared with their previous “status quo” levels.

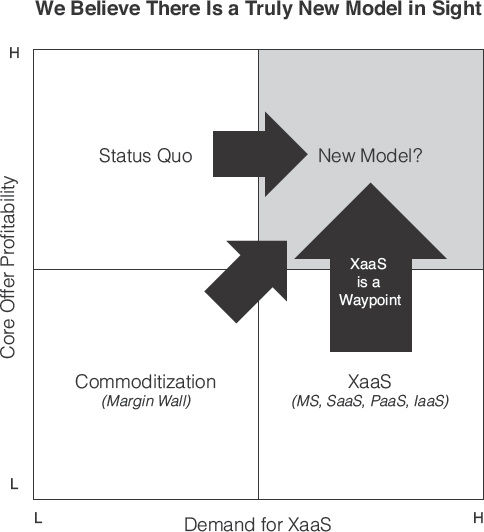

So it begs two fundamental questions: The first one is whether the business and operating model currently known as XaaS is really the new model that suppliers seek. The second is whether the current iteration of the model really makes much difference for customers beyond how they pay and who owns the asset. We think the answer to both questions in the long run is no. We think current XaaS models are waypoints, not a destination. We think there is another new model emerging (see Figure 3.8).

FIGURE 3.8 A Truly New Model in Sight

So far many suppliers and customers have been “casting about” in their search for that new model. We would submit that the casting about has come from the powerful gravitational pull of the past. Rather than approaching the problem from the perspective of what’s now possible, most large suppliers and customers start by thinking about what minor adjustments can be made to what exists today—their current people, their current investments, and their current processes. In other words, what is the minimum number of changes they must make to the status quo? Even in the case of new companies, the people in leadership often design their practices based on what they have done at previous companies during their career. They may innovatively adapt one or two parts, but the rest looks a lot like standard B2B operating procedures. That is completely understandable. But many of those operating principles are still targeted at an old way of working.

It’s the Outcome!

To make a long story short, the search for a “new model” in many high-tech and near-tech industries has been a victim of the Goldilocks principle. Outsourcing was “too heavy,” and current XaaS is “too light.” We need to find a model that is “just right”—and now we think that time has come. We think the complexity arms race that many high-tech companies have engaged in is dead. Business customers are fed up with paying millions to deploy and maintain the complexity that has been handed to them by suppliers. You probably agree: It’s not about hardware and software, or speeds and feeds, or even the number of features anymore.

So the question we will attempt to answer—at least the discussion we want to start—is this: What are we headed to? In other words, what is the next generation of technology-fueled, data-driven operating models between business suppliers and their customers?

Before we begin, we want to jump to the end. Once again, history comes to our aid. In 1992, political strategist James Carville was trying to keep all the internal staff members of Bill Clinton’s US presidential campaign focused on the keys to winning the election. According to legend, he hung a sign in Clinton’s campaign headquarters that read: “It’s the economy, stupid.” Maybe tech suppliers need to hang up their own internal sign now. Because what matters isn’t whether the customer hosts the product or how the pricing works; what matters is the total return they get from those investments—the outcomes they deliver. That is what separates successful CIOs from unsuccessful ones, profitable hospitals from unprofitable ones, and high-efficiency manufacturers from low-efficiency ones. In a rapidly maturing tech industry, it’s about the outcome! And both sides of the B2B divide are about to have a chance to partner much more effectively to unlock its full potential.

Here is our pass at what the evolution of B2B might look like.