Chapter 12

Clearing the Air on Gases

In This Chapter

Accepting the Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases

Understanding the gas laws

Gases are all around you. Because gases are generally invisible, you may not think of them directly, but you’re certainly aware of their properties. You breathe a mixture of gases that you call air. You check the pressure of your automobile tires, and you check the atmospheric pressure to see whether a storm is coming. You burn gases in your gas grill and lighters. You fill birthday balloons for your loved ones.

In this chapter, I introduce you to gases at both the microscopic and macroscopic levels. I show you one of science’s most successful theories: the Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases. I explain the macroscopic properties of gases and show you the important interrelationships among them. I also show you how these relationships come into play in the calculations of chemical reactions involving gases. This chapter is a real gas!

The Kinetic Molecular Theory: Assuming Things about Gases

A theory is useful to scientists if it describes the physical system they’re examining and allows them to predict what will happen if they change some variable. The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases does just that. It has limitations (all theories do), but it’s one of the most useful theories in chemistry. Here are the theory’s basic postulates — assumptions, hypotheses, axioms (pick your favorite word) you can accept as being consistent with what you observe in nature:

Postulate 1: Gases are composed of tiny particles, either atoms or molecules. Unless you’re discussing matter at really high temperatures, the particles referred to as gases tend to be relatively small. The more-massive particles clump together to form liquids or even solids, so gas particles are normally small with relatively low atomic and molecular weights.

Postulate 2: The gas particles are so small when compared to the distances between them that the volume the gas particles themselves take up is negligible and is assumed to be zero. Individual gas particles do take up some volume — that’s one of the properties of matter. But if the gas particles are small (which they are), and there aren’t many of them in a container, you say that their volume is negligible when compared to the volume of the container or the space between the gas particles. Sure, they have a volume, but it’s so small that it’s insignificant (just like a dollar on the street doesn’t represent much at all to a multimillionaire; it may as well be a piece of scrap paper).

This explains why gases are compressible. There’s a lot of space between the gas particles, so you can squeeze them together. This isn’t true in solids and liquids, where the particles are much closer together.

Postulate 3: The gas particles are in constant random motion, moving in straight lines and colliding with the inside walls of the container. The gas particles are always moving in a straight-line motion. They continue to move in these straight lines until they collide with something, either each other or the inside walls of the container. The particles also all move in different directions, so the collisions with the inside walls of the container tend to be uniform over the entire inside surface. A balloon, for instance, is relatively spherical because the gas particles are hitting all points of the inside walls the same. The collision of the gas particles with the inside walls of the container is called pressure.

This postulate explains why gases uniformly mix if you put them in the same container. It also explains why, when you drop a bottle of cheap perfume at one end of the room, the people at the other end of the room are able to smell it right away.

Postulate 4: The gas particles are assumed to have negligible attractive or repulsive forces between each other. In other words, you assume that the gas particles are totally independent, neither attracting nor repelling each other. That said, if this assumption were correct, chemists would never be able to liquefy a gas, which they can. However, the attractive and repulsive forces are generally so small that you can safely ignore them.

The assumption is most valid for nonpolar gases, such as hydrogen and nitrogen, because the attractive forces involved are London forces, weak forces that have to do with the ebb and flow of the electron orbitals. However, if the gas molecules are polar, as in water and HCl, this assumption can become a problem, because the forces are stronger. (Turn to Chapter 6 for the scoop on London forces and polar things — all related to the attraction between molecules.)

Postulate 5: The gas particles may collide with each other. These collisions are assumed to be elastic, with the total amount of kinetic energy of the two gas particles remaining the same. When gas particles hit each other, no kinetic energy — energy of motion — is lost. That is, the type of energy doesn’t change; the particles still use all that energy for movement. However, kinetic energy may be transferred from one gas particle to the other. For example, imagine two gas particles — one moving fast and the other moving slow — colliding. The one that’s moving slow bounces off the faster particle and moves away at a greater speed than before, and the one that’s moving fast bounces off the slower particle and moves away at a slower speed. But the sum of their kinetic energy remains the same.

Postulate 6: The Kelvin temperature is directly propor-tional to the average kinetic energy of the gas particles. The gas particles aren’t all moving with the same amount of kinetic energy. A few are moving relatively slow, and a few are moving very fast, but most are somewhere in between these two extremes. Temperature, particularly as measured using the Kelvin temperature scale, is directly related to the average kinetic energy of the gas. If you heat the gas so that the Kelvin temperature (K) increases, the average kinetic energy of the gas also increases. (Note: To calculate the Kelvin temperature, add 273 to the Celsius temperature: K = °C + 273. Temperature scales and average kinetic energy are all tucked neatly into Chapter 1.)

Relating Physical Properties with Gas Laws

Various scientific laws describe the relationships between four important physical properties of gases:

Volume

Pressure

Temperature (in Kelvin units)

Amount

This section covers those various laws. Boyle’s, Charles’s, and Gay-Lussac’s laws each describe the relationship between two properties while keeping the other two properties constant; in other words, you take two properties, change one, and then see its effect on the second. Another law — a combo of Boyle’s, Charles’s, and Gay-Lussac’s individual laws — enables you to vary more than one property at a time.

That combo law doesn’t let you vary the physical property of amount. Avogadro’s Law, however, does. And there’s even an ideal gas law, which lets you take into account variations in all four physical properties.

Boyle’s law: Pressure and volume

PV = k

Suppose you have a cylinder that contains a certain volume of gas at a certain pressure. When you decrease the volume, the same number of gas particles is now contained in a much smaller space, and the number of collisions increases significantly. Therefore, the pressure is greater.

Now consider a case where you have a gas at a certain pressure (P1) and volume (V1). If you change the volume to some new value (V2), the pressure also changes to a new value (P2). You can use Boyle’s Law to describe both sets of conditions:

P1V1 = k

P2V2 = k

The constant, k, is going to be the same in both cases, so you can say the following, if the temperature and amount of gas don’t change:

P1V1 = P2V2

This equation is another statement of Boyle’s Law — and it’s really a more useful one, because you normally deal with changes in pressure and volume.

If you know three of the preceding quantities, you can calculate the fourth one. For example, suppose that you have 5.00 liters of a gas at 1.00 atm pressure, and then you decrease the volume to 2.00 liters. What’s the new pressure? Use the formula. Substitute 1.00 atm for P1, 5.00 liters for V1, and 2.00 liters for V2, and then solve for P2:

P1V1 = P2V2

(1.00 atm)(5.00 L) = P2(2.00 L)

P2 = (1.00 atm)(5.00 L)/2.00 L = 2.50 atm

The answer makes sense; you decreased the volume, and the pressure increased, which is exactly what Boyle’s law says.

Charles’s law: Volume and temperature

Charles’s law (named after Jacques Charles, a 19th-century French chemist) has to do with the relationship between volume and temperature, keeping the pressure and amount of the gas constant. Ever leave a bunch of balloons in a hot car while running an errand? Did you notice that they expanded when you returned to the car?

Charles’s law says that the volume is directly proportional to the Kelvin temperature. Mathematically, the law looks like this:

V = bT or V/T = b (where b is a constant)

This is a direct relationship: As the temperature increases, the volume increases, and vice versa. For example, if you placed a balloon in the freezer, the balloon would get smaller. Inside the freezer, the external pressure, or atmospheric pressure, is the same, but the gas particles inside the balloon aren’t moving as fast, so the volume shrinks to keep the pressure constant. If you heat the balloon, the balloon expands and the volume increases.

If the temperature of a gas with a certain volume (V1) and Kelvin temperature (T1) is changed to a new Kelvin temperature (T2), the volume also changes (V2):

V1/T1 = b V2/T2 = b

The constant, b, is the same, so

V1/T1 = V2/T2 (with the pressure and amount of gas held constant and temperature expressed in K)

If you have three of the quantities, you can calculate the fourth. For example, suppose you live in Alaska and are outside in the middle of winter, where the temperature is –23°C. You blow up a balloon so that it has a volume of 1.00 liter. You then take it inside your home, where the temperature is a toasty 27°C. What’s the new volume of the balloon?

First, convert your temperatures to Kelvin by adding 273 to the Celsius temperature:

Inside: –23°C + 273 = 250 K

Outside: 27°C + 273 = 300 K

Now you can solve for V2, using the following setup:

V1/T1 = V2/T2

Multiply both sides by T2 so that V2 is on one side of the equation by itself:

[V1T2]/T1 = V2

Then substitute the values to calculate the following answer:

[(1.00 L)(300 K)]/250 K = V2 = 1.20 L

It’s a reasonable answer, because Charles’s Law says that if you increase the Kelvin temperature, the volume increases.

Gay-Lussac’s Law: Pressure and temperature

Gay-Lussac’s Law (named after the 19th-century French scientist Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac) deals with the relationship between the pressure and temperature of a gas if its volume and amount are held constant. Imagine, for example, that you have a metal tank of gas. The tank has a certain volume, and the gas inside has a certain pressure. If you heat the tank, you increase the kinetic energy of the gas particles. So they’re now moving much faster, and they’re hitting the inside walls of the tank not only more often but also with more force. The pressure has increased.

Gay-Lussac’s Law says that the pressure is directly proportional to the Kelvin temperature. Mathematically, Gay-Lussac’s Law looks like this:

P = kT (or P/T = k at constant volume and amount)

Consider a gas at a certain Kelvin temperature and pressure (T1 and P1), with the conditions being changed to a new temperature and pressure (T2 and P2):

P1/T1 = P2/T2

If you have a tank of gas at 800 torr pressure and a temperature of 250 Kelvin, and it’s heated to 400 Kelvin, what’s the new pressure? Starting with P1/T1 = P2/T2, multiply both sides by T2 so you can solve for P2:

[P1T2]/T1 = P2

Now substitute the values to calculate the following answer:

P2 = [(800 torr)(400 K)]/250 K = 1,280 torr

This is a reasonable answer because if you heat the tank, the pressure should increase.

The combined gas law: Pressure, volume, and temp.

You can combine Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, and Gay-Lussac’s Law into one equation to handle situations in which two or even three gas properties change. Trust me, you don’t want me to show you exactly how it’s done, but the end result is called the combined gas law, and it looks like this:

P1V1/T1 = P2V2/T2

P is the pressure of the gas (in atm, mm Hg, torr, and so on), V is the volume of the gas (in appropriate units), and T is the temperature (in Kelvin). The 1 and 2 stand for the initial and final conditions, respectively. The amount of gas is still held constant: No gas is added, and no gas escapes. There are six quantities involved in this combined gas law; knowing five allows you to calculate the sixth.

For example, suppose that a weather balloon with a volume of 25.0 liters at 1.00 atm pressure and a temperature of 27°C is allowed to rise to an altitude where the pressure is 0.500 atm and the temperature is –33°C. What’s the new volume of the balloon?

Before working this problem, do a little reasoning. The temperature is decreasing, so that should cause the volume to decrease (Charles’s Law). However, the pressure is also decreasing, which should cause the balloon to expand (Boyle’s Law). These two factors are competing, so at this point, you don’t know which will win out.

You’re looking for the new volume (V2), so rearrange the combined gas law to obtain the following equation (by multiplying each side by T2 and dividing each side by P2, which puts V2 by itself on one side):

[P1V1T2]/[P2T1] = V2

Now identify your quantities:

P1 = 1.00 atm; V1 = 25.0 liters; T1 = 27°C + 273 = 300. K

P2 = 0.500 atm; T2 = –33°C + 273 = 240. K

Now substitute the values to calculate the following answer:

V2 = [(1.00 atm)(25.0 L)(240. K)]/[(0.500 atm)(300. K)] = 40.0 L

Because the volume increased overall in this case, Boyle’s Law had a greater effect than Charles’s Law.

Avogadro’s Law: The amount of gas

Amedeo Avogadro (the same Avogadro who gave us his famous number of particles per mole — see Chapter 9) determined, from his study of gases, that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of gas particles. So Avogadro’s law says that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the number of moles of gas (number of gas particles) at a constant temperature and pressure. Mathematically, Avogadro’s law looks like this:

V = kn (at constant temperature and pressure)

In this equation, k is a constant and n is the number of moles of gas. If you have a number of moles of gas (n1) at one volume (V1), and the moles change due to a reaction (n2), the volume also changes (V2), giving you the equation

V1/n1 = V2/n2

Standard pressure: 1.00 atm (760 torr or mm Hg)

Standard temperature: 273 K

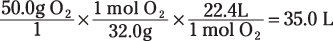

This relationship between moles of gas and liters gives you a way to convert the gas from a mass to a volume. For example, suppose that you have 50.0 grams of oxygen gas (O2) and you want to know its volume at STP. You can set up the problem like this (see Chapters 9 and 10 for the nuts and bolts of using moles in chemical equations):

You now know that the 50.0 grams of oxygen gas occupies a volume of 35.0 liters at STP.

If the gas isn’t at STP, you can use the combined gas law (from the preceding section) to find the volume at the new pressure and temperature — or you can use the ideal gas equation, which I show you next.

The ideal gas equation: Putting it all together

If you take Boyle’s law, Charles’s law, Gay-Lussac’s law, and Avogadro’s law and throw them into a blender, turn the blender on high for a minute, and then pull them out, you get the ideal gas equation — a way of working in volume, temperature, pressure, and amount of a gas. The ideal gas equation has the following form:

PV = nRT

The P represents pressure in atmospheres (atm), the V represents volume in liters (L), the n represents moles of gas, the T represents the temperature in Kelvin (K), and the R represents the ideal gas constant, which is 0.0821 liters atm/K-mol.

The ideal gas equation gives you an easy way to convert a gas from a mass to a volume if the gas is not at STP. For instance, what’s the volume of 50.0 grams of oxygen at 2.00 atm and 27.0°C? The first thing you have to do is convert the 50.0 grams of oxygen to moles using the molecular weight of O2:

(50.0 grams) • (1 mol/32.0 grams) = 1.562 mol

Now take the ideal gas equation and rearrange it so you can solve for V:

PV = nRT

V = nRT/P

Add your known quantities to calculate the following answer:

V = [(1.562 mol) • (0.0821 L atm/K-mol) • (300 K)]/2.00 atm = 19.2 L