I

In October of 1988 I took Francis Bacon to Moscow, an unimaginable intrusion of Western culture into the heart of the Soviet system. I was only 32 but I’d known the world’s greatest living artist since childhood. He was a friend and from my adolescence onwards I spent a lot of time in his company. I joined him for drinks at the Ritz and accompanied him on his champagne benders around Soho, dining with him in the Greek restaurant The White Tower, which he loved, and conspiring with him as we stood in the sticky corners of The Colony Room (he rarely sat).

But this does not fully explain how I found myself in the USSR just as it was teetering on the edge of its own destruction, under twenty-four-hour surveillance by the KGB and side-lined by the British establishment. More than that, I felt morally responsible for the thirty or so works of Bacon’s due to be shown in the exhibition, and I was falling in love with a beautiful Russian fashion designer.

I could say it was Sergei Klokov’s doing. He was the fixer, a man who knew how to make the impossible happen in Moscow and was willing to do almost anything to ensure that it did. It was Klokov who introduced me to the ravishing Elena Khudiakova. But the story doesn’t begin with Klokov.

It really begins with James Bond, when I started to read the Ian Fleming books as a boy. I loved the stories and I especially admired the book jackets designed by the British artist Dicky Chopping, their colours and imagery : bones, knives, guns, frogs, everything a child loves. They were of their time and without fully understanding, they ignited my lifelong interest in surrealism. I had unconsciously started collecting.

Art was the family affliction long before I came along. My parents met in Cambridge where my father was studying architecture, and he followed my mother to London where she was studying at the Chelsea School of Art. One of her tutors was Henry Moore. It turned out that my father couldn’t draw well enough to become an architect so he began to paint instead. After they married, they made a living painting murals together, though mostly for friends. My brother and sister, both born some years before me, went to art school in Florence.

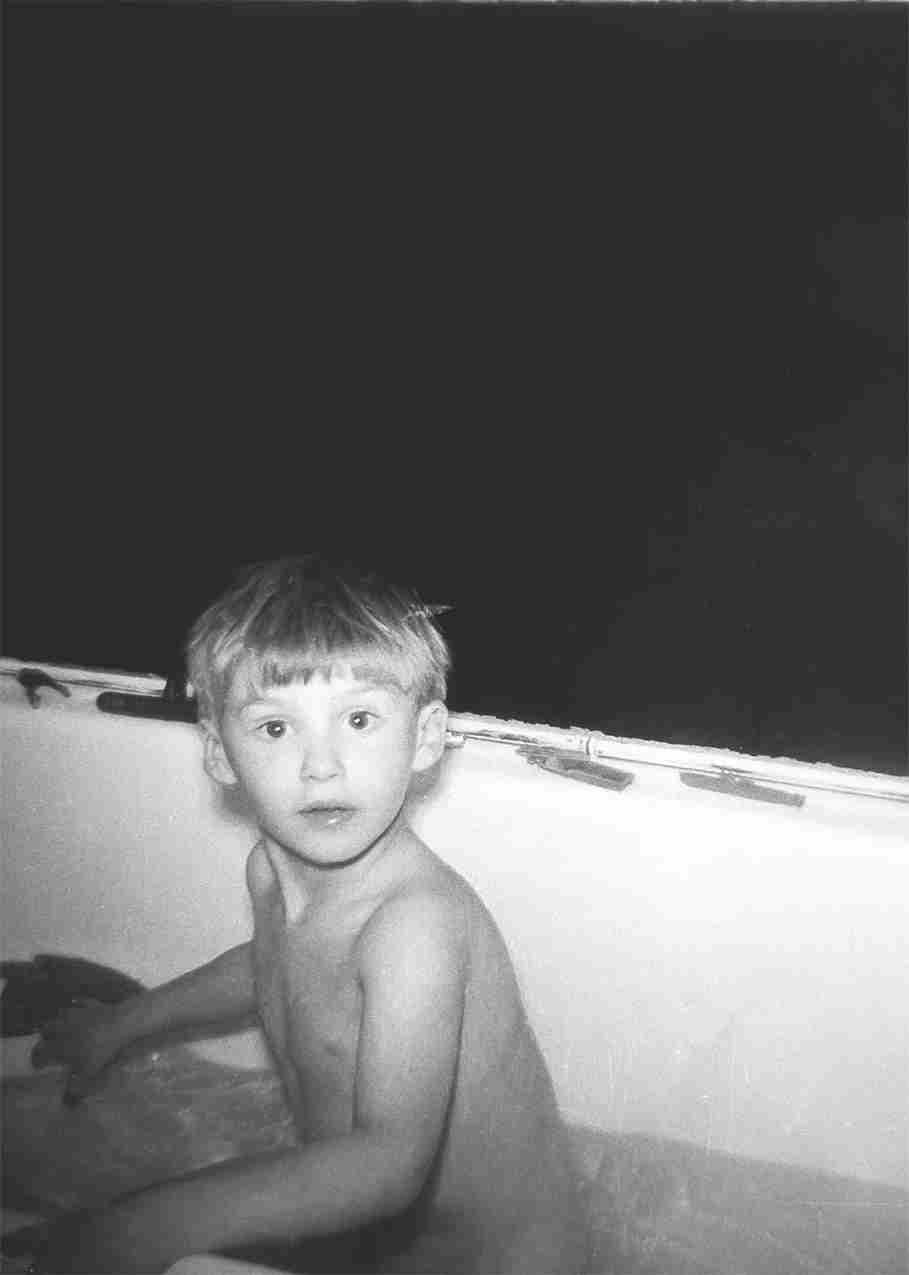

JAMES BIRCH IN BATH. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANCIS BACON.

When my parents visited my siblings in Italy I would go to stay with my grandmother in East Anglia. She lived in a Suffolk landscape of marshes, mud flats, tidal reaches and, at night, thousands of stars. All of which attracted flocks of wading birds and, because it was cheaper than London, artists.

Many of these visiting artists would come to lunch at my grandmother’s. I would also attend, sitting in wonder as a succession of exotic creatures graced the table. Many were well known at the time ; Cedric Morris, John Nash and, to my great excitement, Dicky Chopping, illustrator of the Bond novels, and his partner Denis Wirth-Miller.

Dicky and Denis lived nearby, and when my parents took a cottage in the area the couple became firm family friends. In turn they would often bring their friend, the painter Francis Bacon, to the house. On one occasion as a boy, I was having a bubble bath when the three of them came into the bathroom. Francis found a camera and took a photo of me. I still have it. No one in our household seemed scandalised by this, though a prevalent view of the time was that all gay men must be paedophiles. I do recall that a friend of my mother later asked, ‘What were you doing, letting Francis and Dicky and Denis bath him? How could you leave him with them?’ To which my mother replied, ‘Well, I trusted them completely.’

According to my sister, Jacqueline, they simply thought of me as an ‘angelic child’. Dicky and Denis were family to me and famously kind to the children of their many friends. Later as I grew up I was somehow allowed into the inner sanctum of their friendship with Francis. My dawning awareness of the separation between the man I knew and the great artist he had become began in 1971 at about the age of fourteen, when I bought a copy of Francis Bacon by John Russell. I pored over the pictures in the book and failed to see the nightmarish quality that so many people remarked on. Instead I was struck by the grand theatricality, the images, the vibrant colours and the structure of the work.

Denis and Dicky were Francis’s oldest friends. Francis was in his late forties when the couple introduced him to my parents. They had liked him from the beginning. Contrary to the popular legend of the unhappy, angry man that was suggested by the brutal and tortured imagery of his paintings, my parents found Francis to have a gentle disposition and charming manners.

Dicky and Denis’ Essex idyll at Quay House in the town of Wivenhoe suited Francis’s tastes well ; so well that he would later buy a house there, on Queens Road. Francis would come to paint and Dicky and Denis would bring him to our summer cottage. These visits continued throughout my childhood and into my twenties. I’d find the three of them sloshing down wine at lunch or dinner, or sometimes both. My parents were enthusiastic hosts and the meals often merged into one another. At parties in London, they would often put Francis into a taxi to send him back to 7 Reece Mews only for him to get straight out the other side and return to the throng.

Life in Wivenhoe wasn’t entirely domestic. There was an enticing military garrison at Colchester close at hand. Dicky and Denis treated Colchester like it was a sweet shop, frequently picking up squaddies from the town for casual sex. They would then snip off the brass buttons from their army uniforms as a trophy ; several boxes of buttons were found in Quay House after their deaths.

I knew nothing of these goings-on as a schoolboy but was very conscious then of the web of connections between us all. Dicky, Denis and Francis were, in effect, my uncles.

But Francis was in my life before it had even properly begun ; his story was already caught up in mine. In the 1950s, before I was born, Francis came to our house at Primrose Hill and offered my father two paintings. Francis’s career was really beginning to take off, but he still struggled with money. He was represented by Erica Brausen at the Hanover Gallery in Mayfair. Born in Dusseldorf, Germany, Brausen had helped refugee Republicans to flee from Franco’s Nationalist forces in Spain before, finally, arriving in England with little to her name. She survived through sheer determination and an ability to meet the right people at the right time and then magic money out of them ; key attributes if you are to make it in the art business.

Supported by American tobacco heir Arthur Jeffress, the Hanover opened in 1948 and rapidly became one of the most influential contemporary galleries in London. When later that year Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, walked in, Brausen persuaded him to look at a startling work by a new figurative artist Francis Bacon.

The work, Painting 1946 is now regarded by many critics as the moment when Francis stumbled upon a style that captured the existential fears of a Europe that was contemplating both the reality of the Holocaust and the coming of the atomic age. Being Francis, the artist underplayed the importance of the work, and claimed he was simply trying to paint a bird.

Barr paid £150 for the painting and perhaps the price stayed in Francis’s mind for he suggested the same figure to my father when he came to Primrose Hill, and that was for two paintings, not one. Definitely a bargain, but £150 was a lot of money in those days and my father had to say no.

Barr had no such financial worries and he became an early and enthusiastic supporter of Bacon’s work ; in 1957 he wrote to Brausen describing Bacon as ‘England’s most interesting painter’. But to me he was the nice man who Dicky and Denis would bring to the house ; a man who was interested and kind to me.

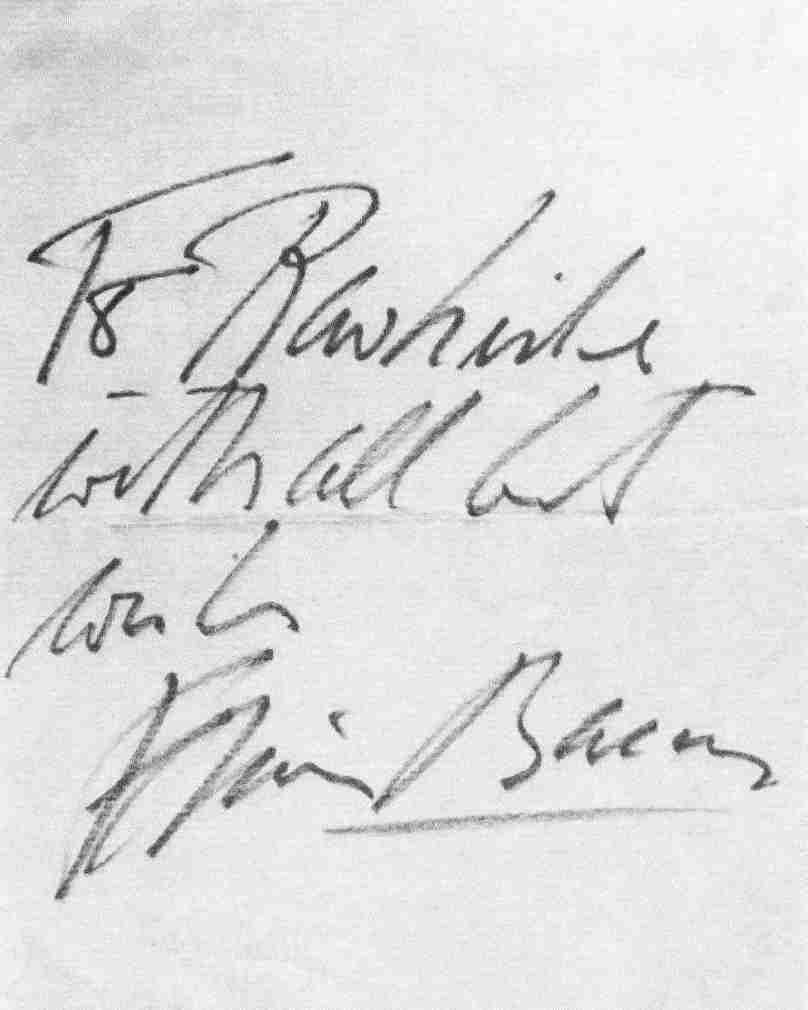

LETTER TO JAMES BIRCH FROM FRANCIS BACON

When I was young, I was obsessed with a TV series called Rawhide, so much so that it became my nickname. This tickled Francis’s sense of humour and he sent me a letter addressed : ‘TO RAWHIDE. WITH ALL BEST WISHES, FRANCIS BACON’. I was thrilled. And like all the things I value, I still have it.

In my teens, on journeys to East Anglia, I would often encounter Francis on the platform at Colchester Junction station, waiting to catch the connection to Wivenhoe, and sometimes we would travel together.

Thanks to the open house policy of both my grandmother and my parents, my sense of what artists are like, how they should be handled, how prickly they can be, how fragile their egos are and above all, how wonderful are the things they create, was formed in my childhood. But I didn’t want to be a painter, I wanted to show paintings ; I wanted to have my own gallery.

By 1983, my childhood dream had become my profession and obsession and, much to the surprise of my family, who had put up with various schemes and plans which ran to greater or lesser success, I had my own gallery at Waterford Road, a street at the far, very unfashionable Fulham end of the King’s Road, miles away from the centre of the art world in Mayfair’s Cork Street and Bond Street in the West End.

Below World’s End the King’s Road was mostly made up of antique dealers, but it was rare for their customers to enter the gallery. There was also a Coral betting shop next door. We opened Monday to Friday. Saturday was pointless because just a few streets away there were football matches at Stamford Bridge stadium, and boozed-up Chelsea fans would stick their heads in and ask, ‘What’s all this fucking shit, then?’

It wasn’t shit to me. I was enamoured of British surrealists and the more experimental contemporary artists who had a similarly esoteric approach to art, especially the Neo Naturists, a group centred around four mercurial young artists, sisters Jennifer and Christine Binnie, Wilma Johnson and Grayson Perry. They were all good but Perry, an angry young man from Essex, a transvestite who also wore black leather motorcycle gear and made fantastic pots and plates in the tradition of English ceramics but with images of teddy bears, sex scenes and motorbikes, fascinated me. They were like nothing I had ever seen. The Neo Naturists would appear at night clubs, galleries or parties wrapped in long coats and then at some point in the evening suddenly disrobe to reveal naked bodies hand-painted with flora, faces or abstract patterns. In 1985, they had issued a manifesto of sorts proclaiming, ‘The Neo Naturists like taking their clothes off for the sake of it.’ But their performance art was more than that, they were an anarchic counterpoint to the increasingly money-driven atmosphere of the London art world. I admired their idealistic anti-materialism. The problem was, if I wanted the gallery to survive, I needed some money coming my way.

In short, I needed to sell art. I needed to discover new artists and build my own stable, and I needed to create events to spark interest in their work from a buying public. This was Thatcher’s Britain and the prevalent mood was, to quote a Pet Shop Boys’ hit of the time, ‘Let’s make lots of money.’ I didn’t want to be rich but I needed to survive, and perhaps that put me at odds with the prevailing spirit but Jennifer and Christine, Wilma and Grayson represented the things that excited me most about art. I wanted to spread the word, I wanted people to know about them and their work. But London was bursting with shows and if I wanted the exhibitions I mounted to compete I had to pursue a share of the limited press attention available.

I hosted numerous promotional parties at the gallery but they brought in little money. Jennifer’s dream was to ride naked on a white horse down the King’s Road, so for the opening of her second show, she did just that. It made the pages of the Evening Standard and the Hammersmith and Fulham Gazette, but that was about it.

It was in November of 1985 that my friend Frances Welsh, who was working on the Standard’s diary pages, and the artist Pandora Monde, a bohemian aristocrat, came up with an idea : they threw a party specifically to introduce people who didn’t know each other.

As much fun as this was supposed to be, I wasn’t sure how it would work out in practice, but I understood the power of meeting people and making connections. So, taking a young artist I was showing at the time, a shaven-headed street poet called David Robilliard, we shut up the gallery and made our way to the venue in Campden Hill Road. We arrived at the house to find an uproarious room crammed with people who hadn’t met each other before but were becoming better acquainted by the minute. I passed through the throng feeling rather shy, unable to see Frances. David had been immediately swallowed up by the crowd. So it was a relief when I recognised Bob Chenciner struggling towards me. An impish and prematurely balding academic who occasionally came into my gallery, Bob was in the fine carpet business, hunting for ‘dragon rugs’ and bringing them into the West from the Soviet Central Asian republics and Caucasus, and more generally he had a keen eye for art and architecture.

He described himself as a ‘cultural entrepreneur’ and regularly visited the USSR where earlier that year Mikhail Gorbachev had become General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. I was aware from the news that Gorbachev had started to talk of two supposedly epoch-making policies, glasnost and perestroika : openness and reconstruction. But as we drank Pandora’s champagne, Bob spoke of a vast, half-starved Soviet empire that had yet to embrace openness or restructuring and remained a terrifying KGB-run country where the ridiculous and the deadly often went hand in hand. Bob had just returned from Ashgabat, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic, 1,597 miles south-east of Moscow.

‘I was dancing in the only nightclub in the entire city,’ Bob hooted in my ear, ‘and my minder, this very eccentric guy called Klokov, said to me, “The KGB have been watching you dance and they’ve just told me that you are doing it with too much enthusiasm. We have to go now !”’ Bob expanded on his theme. ‘James, wherever we went, at some point Klokov would stop me and say, “Bob, we have to go now.”’

That was the first time I heard Sergei Klokov’s name. Though I didn’t yet know it, little in my life would be the same again.

‘So, what exactly does Klokov do?’ I asked.

‘Officially, he’s a diplomat with a special responsibility for culture,’ said Bob. ‘But,’ he paused dramatically, ‘he has other powers.’

These other powers, it seemed, were as much an expression of Klokov’s personality as they were of his shadowy status in the security apparatus. They had, according to Bob, most recently manifested themselves at an airport outside Moscow.

As Bob told it, he and his party were nearing the end of the interminable journey from London to Turkmen and had missed the last onward flight to Ashgabat by a matter of minutes. Klokov took immediate action. ‘He commandeered a military vehicle, put us in the back and drove it out onto the runway, right in front of the plane as it was taxiing for take-off,’ Bob laughed. ‘The pilot stopped, opened the window and shouted down, “What do you want?” Klokov stood up in the back of the jeep, pointed at us and he shouted back up, “This is a cultural delegation !” So they dropped down the steps and let us on the plane.’

I was amused by the idea of this unlikely, plane-stopping servant of the Party, but before our conversation became lost in the growing bedlam, I had my own story to tell. For months a potentially money-making idea had been consuming me, a plan to introduce ten exciting new British artists to the happening art scene in New York.

I had no other theme for this trip than that the artists would all be British, youthful and extraordinary. If they got to New York then maybe they would get some attention and it would be fun.

I had travelled between London and New York for several years in the late 1970s and I knew my way around the art world there, but getting this project off the ground was proving harder than I had anticipated. A group exhibition would be fantastically expensive and, even if I pulled it off, the show would be just one event amongst hundreds of others in a city teeming with galleries. It was clear that I would need to call in as many favours as possible from friends over there. It was ambitious but, in those days, I didn’t worry about things not working out ; I just tried to make them happen.

Bob looked dubious as I explained my master plan.

‘It’s obvious,’ he said. ‘Don’t go to New York, take your artists to Moscow.’

I took a gulp of champagne and contemplated this outlandish idea. The difficulties of the New York plan paled into insignificance.

Bob elaborated. There couldn’t be a better moment : ‘a new spirit of openness’, ‘a rumoured relaxation of cultural censorship’.

‘Everything is in a state of flux,’ he said. ‘Anything is possible. Why not be the first to take advantage of it? If you opened in Moscow, you would be the only show in town. You’re bound to get a reaction from press and public alike. You wouldn’t be able to sell anything, but it would be a sensation James … no Western artist has shown in Moscow for forty years.’

He stared at me, waiting for my reaction. ‘Well?’

‘But how could I possibly do it?’

‘Klokov will fix it,’ he said airily, taking another glass from a passing tray. ‘Klokov can fix anything. He’ll be in Paris soon for a Soviet architecture exhibition, just go along to the Soviet section of UNESCO and say Bob sent you.’

‘Just walk in? How will I recognise him?’

‘Look for a tall Russian, with a beard and glasses.’

Any more detail I might have garnered about Sergei Klokov that evening was lost in the melée of faces and voices around us as somebody else claimed Bob’s attention. A few hours and much drink later I caught up with him again, when the crowd briefly opened to offer him up.

‘Go to Paris,’ he said. ‘I’ll tell Klokov that you’re coming.’

David and I left the party.

David Robilliard made works on paper, with poems underneath. I liked his work, he had a very confident line and lots of people had come to the private view of his show. Unfortunately, none of them had bought anything. Many artists would have been disappointed, but David wasn’t. He had a great attitude to life and he was very funny. He was sorry, he said, not disappointed. But I was. I knew you had to seriously engage with David’s work for it to really make sense and I was beginning to understand that buyers of unusual experimental material were just not present in London.

I had hoped David would find such collectors in New York (and later he did), but in the days following the party I thought more seriously about Bob’s idea. Imagine the effect of showing young artists like David and Grayson in a Communist country where the audience would have never seen anything like their work before. I presumed that most Russians would have no conception that artists like this, and their ideas, existed.

And what if — my imagination slightly running away with me at this point — at the forefront of perestroika, they were to become the artists that opened up the Soviet Union? The creative bridge between East and West? At this point my idealism knew no bounds, but if it happened, the novelty of having had a show in Russia would be an enormous boost to the artists’ careers, and on their return to London I could curate an incredible show.

Back then I had only a slight interest in the USSR. My knowledge was limited, stretching no further than a few constructivist artists, the odd social realist painting and what my mother had told me of her experience on an Intourist tour in 1971. Being an artist herself, and a communist in her youth, she wanted to see the Hermitage, but like so many other travellers to Russia, on her arrival she was disappointed to find herself herded around the country on a state-controlled tourist trip. When her group visited Samarkand to view the Islamic architecture, a sheep was slaughtered in front of them and then served, three hours later, in a stew so tough it was inedible. Mum had been a vegetarian ever since. ‘I just thought, what an unnecessary waste of a life,’ she told me.

Despite Mum’s travails, the idea of going to the Soviet Union seemed increasingly attractive, and what harm could there be in taking the trip to Paris?

I had friends I could stay with in St Germain. I knew the UNESCO building very well, a three-winged modernist spacecraft parked on the Place de Fontenoy. So, why shouldn’t I look in at the Soviet section?

I called Bob.

‘Bob, I think I will go and see this Klokov guy. Does he speak English?’

‘Klokov speaks a bit of everything : English, French, German.’

‘Will I understand him, is his English good?’

‘Of course, he went to the KGB Academy in Tashkent. It’s one of the things they learn.’

So I booked a train ticket to Paris.

Two days before I was due to go, I came down with flu and almost called the trip off. But fate took a hand ; that week Soviet Secretary General Mikhail Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan met for arms talks in Geneva. It was their first meeting and the two leaders established an immediate rapport ; a photograph of them laughing together in front of a roaring fire had gone around the world. The image was appropriated by a power company and now a giant Gorbachev and Reagan, ‘happiness is a warm fire’, appeared on billboards across London. It seemed like a portent of the potential thaw in East—West relations as I shivered and sneezed my way to France and a thaw that might serve my purpose very well.

I felt no better when I got to the Gare du Nord. I took a taxi to the apartment of my friend Eric Mitchell and his girlfriend Françoise Michaud on the Rue des Carmes. They took one look at my pallid face at the door, turned me around and marched me to their local Vietnamese restaurant, where they fed me bowls of fiery chilli soup to burn out the cold — a cure I’ve used ever since.

When I woke the next morning, the fever had gone. Lightheaded, I set off clutching my portfolio of sketches and slides I had brought. I had no idea if I would even be allowed into the Soviet section of UNESCO. Nevertheless, I presented myself with the confidence of someone who has nothing to lose. That is to say, I was utterly unprepared for an encounter that would change my life. Approaching the first man I saw at the Soviet section I said, ‘I’d like to talk to Sergei Klokov.’

‘Yes, that way,’ the man replied and directed me, without further ado and much to my surprise, towards a dark internal staircase as though it was the easiest request in the world.

What did I expect to find at the foot of the steps : an apparatchik, a sinister party man in a grey suit, representative of what Reagan had once called ‘the evil empire’, speaking in heavily accented broken English? Certainly not the man who was waiting for me. As Bob had promised, Klokov was tall and brown-haired, with a Tsarist beard. He was wearing mirrored Easy Rider shades and stood at the centre of a long, bright room filled with Russian contemporary art. Behind him a large window overlooked the École Militaire and the Eiffel Tower. His clothes were black : black shirt, black trousers, black leather jacket, and he held a man’s handbag. In the coming months I was to learn that most Russian men carried one of these bags, in which they kept their vodka and other vital paraphernalia. To me, he looked like a hairdresser.

He held his hand out and said ‘Hello,’ then, gesturing at an oil painting of a wooden hut in a birch forest, he asked, ‘What do you think?’

I tried to be diplomatic. ‘It’s rather good.’

‘It’s a load of shit.’

His English was touched with American. It wasn’t unattractive but it wasn’t quite natural either. Mid-Atlantic, ersatz, it was as though the KGB had trained him to sound like a bad British DJ.

I introduced myself. ‘I’m a friend of Bob Chenciner, he said you were the person to talk to about taking British artists to Moscow.’

‘To Moscow?’

Klokov took off his sunglasses. His eyes were almost black, so dark that you could see nothing behind them. I had no idea what he was thinking or feeling. The beard made it difficult to be certain of his age, but later it was revealed that he was 30, only a year older than I was. He seemed much more confident and experienced than me in this environment, and to my surprise the mood in the room seemed very relaxed.

‘I know that this would have been impossible before but I thought with perestroika and glasnost that …’

I faltered in the face of his unswerving gaze.

‘Well,’ I continued. ‘Bob said you were the right man.’

Klokov put the glasses back on. ‘I am the right man. What art do you want to take to Moscow, James?’

‘Ten new young artists that I believe in.’

‘Revolutionary?’ Klokov asked.

‘Some of them, perhaps.’

‘Good, we need revolutionaries. We don’t have any in Moscow.’

Klokov walked me round the exhibition of contemporary drawings and paintings. Some were figurative, some were architectural. They were well executed and attractive in their way but painted by people apparently unaware of any advances in art since the mid-fifties. As we looked at the pictures, Klokov talked about just why modern Russian art was so bad, the backwardness of Soviet cultural policy and the best hotel bars in Moscow for Western cocktails. I listened, bemused. Could this really be a representative of the Soviet state?

ELENA KHUDIAKOVA IN A DRESS DESIGNED BY HERSELF

PHOTOGRAPH BY GRAYSON PERRY

As Klokov was talking, a minor Soviet official came into the room carrying a stack of papers. Klokov’s face immediately turned his way. Unnerved, the man dropped the files.

‘Typical !’ Klokov burst out, and banged his forehead with the flat of his palm. ‘These Russians can’t do anything without me telling them what to do. Bureaucratic masturbators !’ The man scrambled to gather his papers and left. Up until now I had thought of Klokov as simply slightly unreal but clearly he had status, power over others. I was reminded of Bob’s warning : ‘Klokov is always hyper — he specialises in making scenes in public, it’s like performance art.’

Now calm again, Klokov asked if I cared for coffee from the UNESCO cafeteria. If so, perhaps I had some French currency on me? Unfortunately, he’d just arrived from Russia and only had roubles. I gave him two hundred francs* and he left. When he returned he was carrying three coffees on a tray. The extra cup was for a woman who entered the room behind him.

‘Please James, this is Elena Khudiakova,’ he announced, as if he were presenting me with a gift.

At that time, no one had a clue that seventy years of Communist Party rule were coming to an end, and most of us in the West still had a decades-old view of the Soviet Union. Brezhnev had died in 1982 but his brooding presence was more real to us than Gorbachev, still relatively new to the scene ; to most people perestroika and glasnost remained just catchphrases. In our collective consciousness, they had yet to fully replace our vision of a dictator state with its KGB and its gulags. The general view of Russian women in 1985, if they came to mind, was equally backdated : either the beautiful Lara from Doctor Zhivago wrapped in fur, or rounded babushkas of indeterminate age, in oversized coats, hats and felt boots, sweeping the snow and melting ice from Red Square.

Elena Khudiakova was anything but a rounded babushka of indeterminate age. Tall and athletic, she was in her early twenties. Her skin was almost supernaturally pale, her dark hair cut in a geometric bob above sculpted Slavic cheekbones. She was dressed as if she was going to a high-end roller disco in designer jeans, t-shirt and Christian Dior sunglasses. She seemed to me extraordinary.

Master of the scene, Klokov allowed the silence to last a little bit longer than necessary. I managed a ‘hello’, before he continued the introduction.

‘In Moscow, James, Elena is a high priestess of fashion design.’

I smiled at Elena, but my smile wasn’t returned.

‘And James, I understand,’ Klokov said, ‘wants to bring his artists to Moscow.’

I found myself attempting clumsy conversation. How long would Elena be in Paris for? Her English was less fluent than Klokov’s. She spoke slowly, her voice was light and warm.

‘Not long I’m afraid. I here to work. I design Russian architectural show UNESCO. When exhibition finishes, I must go.’

‘What a pity.’

‘No, it is a great privilege for Elena to be here,’ interrupted Klokov. ‘Her present boyfriend is the head of a local Communist party in Moscow.’

I wasn’t sure how to react to this revelation.

‘Is he still in Moscow?’ I enquired.

Elena looked across to Klokov, waiting for his assent before she answered.

‘Yes.’

So, if Klokov wasn’t Elena’s boyfriend, was he her boss? Certainly, when he gave commands Elena acted, but so did everyone else around him.

When Klokov suddenly announced, ‘Now we will go for lunch,’ I automatically reached for my coat, but Klokov raised a hand. ‘First we must have a picture James.’ A photographer appeared — where Klokov summoned him from I could not say — and our number increased as previously unseen members of the Soviet cultural mission emerged and stood alongside us. This amused me and I looked to Elena to see if it amused her too, but her face was set on the camera. As I came to understand, having her picture taken, even in these faintly ridiculous circumstances, was always a completely serious matter to Elena.

I presumed it would just be Klokov and I that would be going to the restaurant, which turned out to be one of the many small but expensive bistros in the streets around UNESCO. But Elena also came, carrying large paper shopping bags, as did two men from the Soviet mission introduced by Klokov as Sasha Kamenski, ‘a goldsmith and sword-maker’, and Emile Mardacany, ‘a colleague’, later I was to learn that he was Klokov’s second in command.

In the bistro Elena sat on Klokov’s left, I sat on his right. Sasha and Emile were opposite us. We were in orbit around Klokov. Just as he liked it, I guessed. The Russians all chose exactly the same meal. They ate steak and chips and drank red wine while I showed Klokov slides of work by the artists I wanted to take to Moscow. Between mouthfuls and gulps Klokov nodded at each slide and gave his opinion.

‘Yes, this is good.’

‘I like this very much.’

‘They will like this.’

‘Not so good but it has spirit.’

When he wasn’t talking, he emitted a series of resonant humming noises that were pleasant and ominous by turn, so that he dominated the conversation even when he wasn’t saying anything. At one point, when Klokov was engaged in a detailed discussion with the waiter about wine, Emile leaned over the table and said, with some pride, ‘Isn’t his voice mesmerising?’

While I wouldn’t go so far as to say Klokov was mesmerising, I was struck by his charisma. He loved making jokes as we talked and he seemed extremely knowledgeable about a wide range of subjects — in particular he talked about his passion for Asian culture and extolled the virtues of acupuncture and herbal medicine — and I was secretly delighted that he seemed to like my artists’ work.

Halfway through the main course, Elena left the table with her bags. She returned wearing a remarkable new outfit. It combined a pleated 1920s-style skirt barred in bold blue and yellow with a short-sleeved boxy blouse emblazoned with the large retro red star of communism. The effect was unique, as if she were about to appear in a Wham ! video directed by Sergei Eisenstein. I turned back to Klokov to find he hadn’t noticed her change of dress or, if he had, it was far too small a thing to concern him. His mood had changed. He was now less hopeful about the possibility of a show and asked me if the artists had shown before.

‘Yes, all of them in London, one in New York and another in South Africa.’

‘South Africa?’ Klokov said tersely. ‘Great, why don’t you say Israel as well? You must know that these countries are not friends of the USSR.’

In order to brighten the mood, I ordered two more bottles of wine which quickly appeared at the table. Klokov cheered up. Perhaps it could be done after all.

‘But you will need to write a letter, James, and it must go to the right people or it will be lost forever. On no account write to the Ministry of Culture.’

‘No?’

‘No. You must write to Tahir Salahov, the head of the Union of Artists. Only the Union of Artists deals with the work of living painters in the USSR and internationally.’

He explained how to word the letter and even how to address it. I was on ‘no account’ to post the letter to the USSR ; it would not be delivered. The only certain way of it reaching the Union of Artists was to give the letter to somebody who was going to Moscow and ask them to drop it off. I thought he might be pulling my leg but Klokov was deadly earnest, this was the most important thing to understand. Sasha and Emile nodded gravely.

‘Do not think of posting the letter,’ he repeated. ‘It will be impossible.’

Klokov had been drinking steadily and at great volume without once visiting the lavatory. When he did finally seek out the cloakroom, a clear space opened up between us. I looked to my left, and I realised just how beautiful Elena was. She had changed again, this time into a black silk shift dress that revealed her winter-white shoulders.

In Klokov’s absence she continued the conversation with me in her fractured English. ‘What is fashionable in London?’ ‘Do you know Pink Floyd?’ She was genuinely interested and eager for any scrap of information I could give her. She also seemed to have learnt a stock of rather old-fashioned English phrases.

‘Don’t mention it.’

‘This is very prestigious.’

‘Thank you for asking.’

‘Oh, he is quite important, he is a diplomat,’ — this last pronounced with a long, rolling ‘aaa’ which I found, I admit, very engaging.

‘Do you have plans for tonight?’ I asked. Even as I said it I sounded a little gauche. ‘If you’re free I was thinking of Les Bains Douche, it’s the best night club in Paris right now, Madonna goes when she’s in town.’

‘They will not let me out,’ she said matter-of-factly. ‘We locked in apartment after six o’clock.’ How naive I’d been. I was startled back into silence.

Klokov returned and, sensing that something had passed between us that had escaped his jurisdiction, brought lunch to an end in the same brusque manner he had begun it.

‘Enough ! We are finished. James, write that letter !’ Chairs were pushed back, coats, hats and scarves were passed to and fro, dropped and picked up again ; the elaborate ballet of slightly drunk Russians finishing a good meal. A waiter approached with the bill. ‘Yes, yes,’ said Klokov and nodded in my direction. The others turned and thanked me warmly. It had been so kind of me to buy them lunch. I had no choice but to reach for my wallet.

‘Out of interest,’ I asked Klokov when we were out on the pavement, ‘What do Russians think of Surrealism?’

‘We don’t like it,’ he declared. ‘Life in Russia is surreal enough.’ With that he departed, leading his party up the street ; Elena turned once to fix me with a questioning look, then followed on after Klokov.

I rattled back to London on the train and I mulled over this strange encounter. I had a strong sense that Elena and Klokov were engaged in a practical joke that I wasn’t privy to. The situation felt unreal.

Did Elena really have a Communist Party boyfriend back in Moscow? Was she a designer? Why did she keep changing her clothes? It was only when I went for a drink in the bar on the ferry that I realised Klokov had not even given me the change from my 200-franc note, but I didn’t mind. I was excited at the prospect of this new project.

At Victoria station Gorbachev and Reagan were still smiling down from the billboard. I returned home, sat down and wrote a letter to Tahir Salahov suggesting a visiting exhibition of new British art in Moscow.

‘Such an exhibition,’ I wrote, Klokov’s voice resonating in my ear, ‘could only build upon the new feeling of understanding and cooperation between East and West.’

The next morning Bob called.

‘So, what did you think of Klokov?’

‘He was a remarkable guy, but I think he fleeced me out of 200 francs. Is he hard up?’

‘Klokov? He’s one of the gilded elite, one of the darlings of the Party. Of course he’s hard up.’ Bob roared with laughter.

‘Wait’til you get to Moscow. You are coming, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, I am,’ I said, suddenly certain. ‘But I need to find someone to take a letter to the Union of Artists. Klokov said on no account should I post it.’

‘No, don’t post it ! Give it to Johnny Stuart, he goes to Moscow all the time.’

Johnny was the director of Sotheby’s icon department and outside of Russia was considered the world’s leading expert on icons. He dressed in black leathers and was an aficionado of British motorbikes and rockers. He had learned church Slavonic and his role at Sotheby’s meant he spent a lot of time in Moscow.

I called him at work and he agreed to take the letter as long as I dropped it off at an address he gave me in Notting Hill. Given his occupation I expected to arrive at a grand stucco terrace but Johnny lived in a flat over a garage stuffed with old British motorcycles. I found him working on one of them, barely visible in clouds of exhaust. He was lanky and long haired, and yet still elegant with it, his overalls spotted with engine oil. He turned the motorbike engine off and ambled over, wiping his hands on a dirty rag.

‘James? Sorry about the racket, just tuning up the Triumph. Got a letter for me?’

He reached out a hand black with engine grease. I gave him the letter and he read the address and whistled softly. ‘Tahir Salahov, eh?’

‘Have you met him?’

‘Me? No, he’s too grand for that. I’m just the icons chap. Anyway, have to crack on. Need to fix this before I fly. Don’t worry, I’ll get it there.’

I left Johnny Stuart as I found him, engulfed in noise and smoke.

* The equivalent of £20.00