II

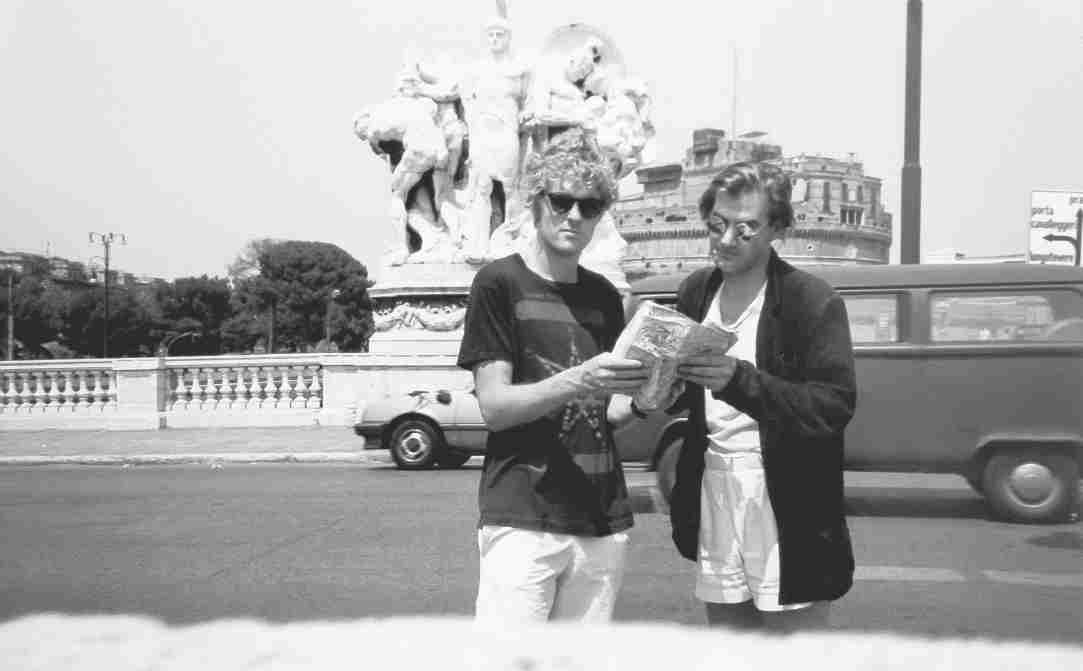

GRAYSON PERRY AND JAMES BIRCH IN ROME

Six months after my letter was taken to Tahir Salahov, General Secretary of the Union of Artists in Moscow, I had heard nothing. That was it then, my lunch with Klokov and Elena had been little more than an incidental Soviet intelligence-gathering operation — though what, I wondered, could Klokov have hoped to gather from me?

Happily, the Neo Naturists were not the kind of artists that pressed you for schedules and long-term plans. They preferred things to be off the cuff.

For now, they were pleased to have my gallery for their shows. But the prospect of the trip to Moscow had temporarily obscured some of the uncomfortable realities of my situation. A show in the USSR would have given us impetus, attracted publicity and, possibly, investment. Without Moscow could I continue to operate the gallery on the King’s Road? I wasn’t making a lot of money from the Neo Naturists. That had never been my ambition, but I was also failing to put them on a larger stage, which was galling because I knew they were ready for it. It was clear that an artist like Grayson, young and little known outside London’s contemporary art scene, would be successful once he had a bigger audience. His work was unique.

Grayson came from Chelmsford, the sort of small English town that didn’t clutch cross-dressing sons to its bosom. Fiercely bright, he had been rejected by a family that couldn’t comprehend his difference. He was angry about that and angry too with an art world that didn’t appear to value him ; he felt he was up against a hierarchy of taste that was conventional in its sensibility.

I was introduced to Grayson by Jennifer Binnie, who he was going out with at the time. After her first show at my gallery she had asked if I would look at her boyfriend’s work. When I got to their squat at Crowndale Road in Camden Town, Grayson took me up to his room and showed me a row of plates and pots he had made at evening classes. My heart jumped.

I gave Grayson two shows. Then in the spring of 1986, an Italian curator arrived in London gathering work for a group exhibition. On a recommendation he rang me up : ‘What was new? What was good?’ I showed him work by Grayson and he chose three pots on the spot. So it was that, in early July 1986, now convinced that Moscow wouldn’t be happening, Grayson and I stepped off a plane in Rome.

Neither Grayson nor I had been to Rome before. We hired a motorbike and had fun riding around the city, weaving through the traffic jams beside the Coliseum. But as I hung on at the back of the bike I wondered, a little wistfully, about what it would have been like to have taken Grayson’s art to Moscow. I had discussed the proposition with him — there would be no exhibition if Grayson and the other Neo Naturists objected to it on political grounds. But as the months passed and the opportunity seemed to have waned, we stopped talking about it and began thinking about other prospects.

I believed (and still believe) in the power of art. Back then the world was divided into two heavily armed camps bristling with nuclear weapons but I felt art could slip through the battle lines and open people’s minds to new ideas. I knew that it would be hard to do, perhaps impossible, but it seemed to me to be worth the effort. Even as we whizzed across the Piazza del Popolo, helmetless and with the Roman sun hot on our faces, I was mourning our lost trip to Moscow. It was such a mad, brilliant opportunity of sorts. And I realised, now that it wasn’t happening, how high my expectations had grown for my artists, for the gallery and for myself.

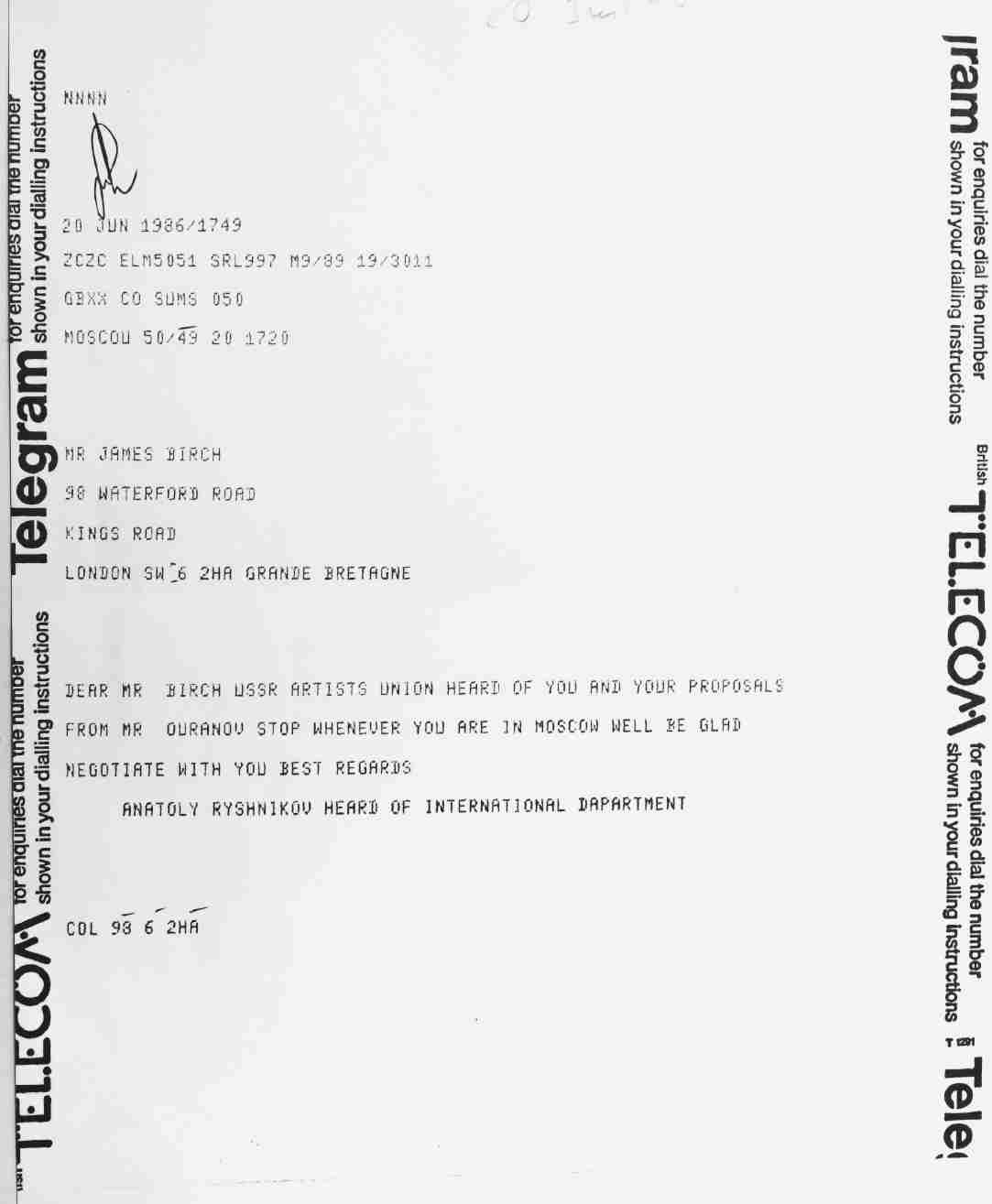

TELEGRAM FROM THE UNION OF ARTISTS

But fate and destiny march to their own drum and I had only been back in London for a few days when a telegram came from Moscow. The spelling was eccentric and I didn’t recognise any of the names.

DEAR MR BIRCH USSR ARTISTS UNION HEARD OF YOU AND YOUR PROPOSALS FROM MR OURANOV STOP WHENEVER YOU ARE IN MOSCOW WELL BE GLAD NEGOTIATE WITH YOU BEST REGARDS ANATOLY RYSHNIKOV HEARD OF INTERNATIONAL DAPARTMENT.

I presumed it had been sent under the instruction of Tahir Salahov. Was this it, was I going? I couldn’t be sure. Nevertheless it was thrill enough to hold the telegram in my hand. I rang the artists to tell them. It was the next step.

I called Bob, hoping he’d be in London and not hunting carpets in the Caucasus. He picked up, jaunty as ever. ‘Great timing James, I’m just back from Baku.’

‘I’ve had a telegram Bob. But I’m not sure if this is an official invite or not.’

I read out the message. ‘“Whenever you are in Moscow we’ll be glad to negotiate with you.” Is that an invite?’

‘James, it’s the red carpet,’ Bob laughed. ‘It’s a passport to the Soviet Union.’

‘So, I can just go to Moscow?’

‘No, no one can just go to the Soviet Union. You have to be part of an invited group to get in.’

‘But I don’t have a group. I’m just me.’

‘Join my group. I’m flying to Moscow with two National Geographic journalists, you can come on that.’

It seemed almost too good to be true. ‘Who organised this group for you?’ I asked.

‘Klokov of course,’ said Bob. ‘Just go and get your visa.’

In those days there was only one travel agency in London where you could make arrangements for visiting Russia, a Soviet-sanctioned operation located on Kensington Church Street. The process was, in its way, a rehearsal for the intricate difficulties of life in Moscow. First, I had to take the telegram I’d received from Anatoly Ryshnikov to the travel agency to prove that I really had been invited to the USSR. Then the agent had to telex a copy of the invitation back to the appropriate state ministry in Moscow which then, if it was approved, would send back provisional permission for my visa. Finally, I should present myself at the Soviet Consulate, also in Kensington, where, hopefully, the provisional permission would have arrived. Then, in turn, if the consulate was satisfied, the visa would be issued.

I arrived at the Soviet consulate on Kensington Palace Gardens early in the morning. I had to wait for most of the day and, as each hour passed, I felt a little more edgy. Eventually, it was my turn to meet a stone-faced Soviet official. I greeted him warmly and held out my hand for him to shake. There were no reciprocal pleasantries.

I grew more nervous still when he turned his attention to what was, I began to fear, an inappropriate get-up. What should you wear for this occasion, to seem both respectable but not overly capitalist? I had worn a suit but had not been able to find a tie.

He cast an unimpressed eye over my Doc Martens.

‘You are to be a guest,’ he asked with some suspicion, ‘of the Union of Artists?’

‘That’s right. Yes.’

He considered this for a moment then, for reasons he clearly didn’t have to tell me, stuck the visa into my passport and stamped it. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had smiled upon my application.

Bob picked me up from my home in Fulham in a taxi on the morning of Tuesday, 15 July 1986. My bags were packed, a picture of my eleven-year-old daughter Zoe was, as always, safely stored in my wallet — Zoe didn’t live with me, so I always carried a photograph of her. At Bob’s suggestion, I had also included a packet of chocolate digestive biscuits in case we were short of food. Once through passport control at Heathrow, Bob steered me into duty free where he bought several bottles of whisky and suggested I did likewise. I had thought we were going to the land of cheap vodka but I was behind the times. As well as introducing perestroika and glasnost, Gorbachev was attempting to tame the Soviet Union’s catastrophic alcohol problem. At Gorbachev’s instigation, the Central Committee of the Communist Party had passed a resolution on ‘Measures to Overcome Drunkenness and Alcoholism and to Eradicate Bootlegged Alcohol’. The state, which made all the vodka at the time, had drastically reduced production by 30 per cent and raised the price of what was left. Good quality alcohol at a reasonable cost was increasingly hard to get hold of and, said Bob, we’d need it for presents. ‘They like their whisky.’

Ballpoint pens were also at a premium and Bob suggested we pick up cartons of Camel and red Marlboro. The Russians were rationed to 1,200 cigarettes a month per person, or forty cigarettes a day. These Soviet cigarettes, called Papirosy, were made up of half rough tobacco and half a roll of long cardboard that you squeezed into the form of a filter. There were three brands : ‘White Canal’ named after the series of ship canals north-east of Leningrad, dug by gulag prisoners in the 1930s at the cost of 25,000 lives ; ‘Laika’ honoured the first dog to go into space ; and ‘Bogatyry’ had a Kazak warrior on the packet. They all smelt the same, bad. Understandably, American cigarettes were a much sought-after alternative.

‘There are virtually no taxis in Moscow,’ Bob explained. ‘But if you wave a car down the driver will pick you up for a cigarette or some roubles.’ This only worked, I would later find out, if you spoke enough Russian to be able to tell the driver where you wanted to go.

The British Airways plane was empty apart from Jon Thompson and Cary Wolinsky, the journalist and photographer on commission from National Geographic, who were sitting in the back. Once in my seat I did a mental check for the twentieth time of all the things I needed to bring with me. Slides, CVs, business cards. Apart from my friend Paul Conran and the artists, I had not discussed the trip with anyone else. It still seemed fantastical.

We landed on a dreary afternoon at Sheremetyevo Airport. From my window seat I observed low grey clouds, military vehicles and a missile launcher armed with two green rockets angled to the sky. Soldiers watched as our plane taxied to the terminal. There was a wire fence at the edge of the concrete apron and, beyond that, an apparently endless birch forest. It was exactly what I had expected to see.

I was glad to recognise Klokov in the terminal building, waiting just inside the door, still wearing his Easy Rider shades. His greeting was muted, as if he too was nervous. Despite his patronage, we were obliged to go through border control, where our passports and visas were checked. It was an unsmiling, uneasy business, though I was more nervous about the large amount of cigarettes and whisky in my bags surviving the customs check than anything else. To my relief when we arrived at the desk Klokov pulled something from his jacket pocket, held it up briefly and we were waved through.

‘What did he just show them?’ I asked Bob under my breath.

‘His KGB badge.’

We were almost out, just one last gateway manned by border guards to go. Klokov went first, Bob followed and I came last. But as I stepped through the gate the alarm went off. Two guards immediately pulled me aside. I looked at Klokov and saw sweat break across his brow.

One guard started patting me down, the other asked questions that I couldn’t understand. My arms were thrust out and my legs pushed apart. My stomach churned, I was nauseous and dizzy. This, then, was what fear felt like. As I was being searched, I looked down at my feet and realised that the steel toe caps in my Doc Martens had set the metal detectors off. Keeping my arms outstretched I nodded at my feet and said, ‘My shoes !’ At the same moment, the guard searching me found a lighter in my pocket with a picture of a nude on it that I had been given in Rome. He was intrigued. The other guard considered my exotic footwear. It had never occurred to me that a pair of shoes could cause so much trouble but the atmosphere eased.

‘Keep it,’ I said to the guard holding my lighter, almost ecstatic with relief. ‘Please !’

When we got outside Klokov swore, ‘ёбты’, ‘Yobti !’ — ‘fuck’ in Russian, blew out his cheeks and threw up his hands in relief.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

‘James. I thought you had a bomb on you.’

I started laughing but when I saw his face, I realised that he was deadly serious.

An informal welcoming committee was waiting for us. The Union of Artists was represented by its Minister for Art Promotion and Propaganda, Mikhail Mikheyev, known by his diminutive plus shortened surname, Misha Mikhev. He was bald, moustachioed, and looked more Italian than Slavic. There was also a small polite woman who touched Klokov on the shoulder. he turned to me and introduced her as his girlfriend Marina.

Once the formalities were out of the way, Misha Mikhev waved us goodbye and the four of us got into Klokov’s boxy car and set out for the city centre. The birch trees ran alongside the road most of the way into Moscow. The forest, vast and dense. As the highway met the city Klokov pointed out a massive jumble of angled steel. This, he explained, was the ‘Ezhi’ memorial.

‘It represents tank traps. James, this is the spot where the Germans were halted in 1941.’

‘They got this close?’ I said.

‘Yes, only a few kilometres from the Kremlin’s walls.’

The memorial was massive. This, it occurred to me, was a country that was very serious about its history. Was it ready for the Neo Naturists?

SERGEI KLOKOV AND JAMES BIRCH IN THE KREMLIN

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT CHENCINER

We had been assigned to the National Hotel, and we were lucky. The National overlooked Red Square and the Kremlin. Grand and ramshackle, it had been opened as a luxury hotel in 1903, just in time for fifty years of revolution and war. The first ever meeting of the Bolshevik government took place in the hotel dining room in 1918, Lenin had lived in room 107 and Trotsky had slept here too. In 1932 the Soviets had mounted a huge mural on top of the building depicting the full industrial might of the Soviet Union. I gazed up at the mural, contemplating the enormous endeavour it represented. To industrialise and collectivise such a huge country in a few short years was an achievement of sorts. No doubt it turned into a foolhardy and often murderous mission but in the face of such ambition the shadow of doubt lengthened over my own plans.

In 1989 the façade of the hotel, like the system it represented, would start to crumble, images of pitheads and powerlines eroding, and chunks of masonry and socialist realist art would fall to the street below. But for now, the National was intact in at least some of its battered glory. Inside there were marbled halls and grand staircases but my room — inserted, I suspected, along with others into what had once been a suite — was tiny. The bed was small, the bedside table was smaller, the light on the bedside table was smaller still. There was a large fridge but it was empty and didn’t work. Unaccountably, there was a pungent smell of rotting apples in the bathroom. I later found that all bathrooms and public conveniences in Moscow had a similar whiff — the effect of vodka on the digestive system. There was no plug for the bath.

I didn’t have time to further consider my situation. I went straight downstairs to meet the others in the bar. To my surprise, Elena was already sitting there and she started asking me more questions about London. Answering her the best I could, I realised that I was delighted to see her.

Although we were all engaged on different missions, Klokov liked to keep his party together. Bob, I presumed, was once more in search of carpets, and Cary Wolinsky and Jon Thompson were attempting to complete a feature provisionally entitled ‘Inside the Kremlin’ though, so far, they had mainly been outside the Kremlin. Wolinksy was unmistakably American, in a plaid shirt, and jeans and Jon Thompson unmistakably English in a well-cut suit. A very accomplished photographer, Wolinsky had crates of gear with him and whenever I encountered the two journalists he was festooned with camera equipment.

Each time they visited, Klokov would progress so far through the delicate negotiations required to get access to the heart of Soviet power and then encounter an official, yet to adopt the new glasnost, who would say no. That meant that Cary had to return to the States, taking all his camera equipment back at enormous expense until Klokov found a new, more enlightened official ready to listen. It was their third attempt to storm the Kremlin.

But this time, said Klokov, things were going to happen. All the signs were good, he insisted, as we knocked our glasses together. At the airport he had been operating under the gaze of a more conventional security apparatus. Here, at the bar, he was free to arrange things as he wished and he was in an altogether more cheerful mood.

‘Tonight,’ he now declared with a grand gesture. ‘We’re going to the home of my great friend Mikhail Anikst to have dinner.’

This news didn’t generate immediate excitement.

‘Who is Mikhail Anikst?’ I asked.

‘Who?’ said Klokov, apparently surprised at my lack of knowledge. ‘He is head designer at the Alexander Press, Russia’s best graphic designer.’

To reach the apartment of Russia’s best graphic designer we drove back out on the route towards Sheremetyevo Airport until we reached a suburb dominated by a series of huge tower blocks. Confusingly, the entrances to these blocks did not face onto the road, but were at the back of the building. The doors had been layered with leather to keep out icy draughts and the worst of the winter weather. In summer, this had a profoundly deleterious effect on the atmosphere within the building, which had no air conditioning. Outside the block, Moscow was already hot and smelly, inside you were hit by a wall of body odour, vomit and urine and vaporised fuel, the cheap petrol that powers cars and generators, and the ever-present acrid smell of 1,000 people each smoking forty Soviet cigarettes a day.

We rose several floors in a perilous lift then disembarked into a shabby communal area. Klokov approached a scuffed door and rapped on it with his knuckles. The door opened but instead of the anticipated mass-produced utilitarian furniture and grey interiors we stepped into something entirely unexpected — the rooms were packed with Russian Empire furniture. Entering the apartment was like calling upon an elderly grand émigré duchess in Kensington.

‘This is fantastic,’ I said out loud. Other guests milled around us, smoking heavily in the Russian way and enjoying a supply of vodka which seemed unaffected by the edicts of the Communist Party’s Central Committee. Amongst the guests I spotted Misha Mikhev, who smiled broadly back, raising his glass, apparently very pleased to see us.

‘Where,’ I asked Klokov quietly as I looked around the room, ‘is Tahir Salahov?’

‘Oh, you will have to deal with Misha for now. He is a very important man,’ Klokov said. ‘Anyway, it is not yet time for Tahir Salahov.’

We had a very good dinner with lots of fresh vegetables, heavy on the dill which I came to see the Russians love, and such enormous amounts of drink that I found myself drifting out of the increasingly raucous conversation.

I was brought out of my reverie by Misha Mikhev. ‘Come James, let us go to the kitchen for coffee and bring your portfolio with you.’

Misha was about ten years older than me and, after an evening drinking vodka, he seemed even more olive-skinned than before.

‘You don’t look very Russian.’

‘No, people think I am Italian,’ he replied. ‘But when I was in Cuba, they thought I was Spanish.’

MISHA MIKHEV AND ELENA KHUDIAKOVA

‘Why were you in Cuba?’

‘To put on an exhibition of Soviet art on behalf of the Union of Artists.’

Now Misha became solicitous, ‘What do you want to do in Russia James?’

He leaned forward and patted my knee in a friendly gesture. The vodka mist cleared a little and Klokov’s words came back to me — Misha is a very important man, I must impress on him how serious I am.

‘I really want to bring English artists to Moscow.’

‘Okay James,’ he said, as if that was all he needed to hear, but in my excitement I went on. ‘They’re great artists, Misha, artists who are trying new things, Jennifer Binnie, Grayson Perry, he makes wonderful pots.’

‘Pots?’ said Misha.

‘Yes pots, and plates.’

Misha considered this with some amusement. ‘Pots are good, yes. Tomorrow we will show you some spaces for your pots.’

‘Thank you, Misha,’ I said earnestly.

‘No problem. And perhaps you can ask some of the friends here what paintings they would like to see? And James —’

I was lost in a vision of the naked body Neo Naturists’ paintings set against a background of ruched curtains and malachite columns in a grand Moscow gallery.

‘Yes?’

‘Be careful with Russian vodka. It is very strong.’