IX

On 18 September, Francis was interviewed in the Sunday Times. ‘It is a great disappointment,’ he said. ‘If it wasn’t for this bloody asthma, I would be over there. I had been looking forward to it. Everything was closed up after 1917. It would have been fascinating to see the country now.’

On the following Wednesday, 21 September 1988, I was invited for breakfast, to collect John and to say goodbye to Francis. Francis cooked us eggs and bacon. On my way out I saw that his suitcases were still packed and waiting by the front door, as if he was expecting to overcome his own fear and come with us. I felt a wave of disappointment.

‘I’m sure you’ll have a marvellous time.’

As we took off at Heathrow, I imagined Gill Hedley of the British Council and her team putting the finishing touches to the hanging. There was no message for me from the British Council. I had to assume that the paintings had arrived safely in Moscow. I knew that a near-military operation had been undertaken to get the pictures to the USSR.

In 1988 the value of the thirty-odd works in the convoy would have been in excess of £20 million. The prospect of a raid while the art was on Soviet territory was too audacious to entertain but the authorities had to be prepared for that eventuality. The pictures were driven through Poland in lorries and then accompanied by an armoured military convoy from the USSR border, which drove all the way to the gallery space at the Central House of the Union of Artists. Gill accompanied them all 1,794 miles from London to Moscow.

Later that day, John, ‘suited and booted’ as he liked to describe it, and I, in a pinstripe suit, a far more sober affair than my Comme des Garçons number, stepped off the British Airways Heathrow—Moscow flight. Klokov and John eyed each other speculatively in arrivals and decided that they liked the cut of each other’s jib. Klokov delivered John to the National Hotel on Red Square, and then he took me to the Hotel Ukraine, a twenty-eight-storey Stalinist wedding-cake Baroque edifice. It was one of the few places where Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol push had been adopted wholeheartedly and the bar had been closed down. I wondered, now that Klokov needed me less, if my currency had fallen or if it simply suited Klokov to keep John and I apart. Quite possibly it was all three.

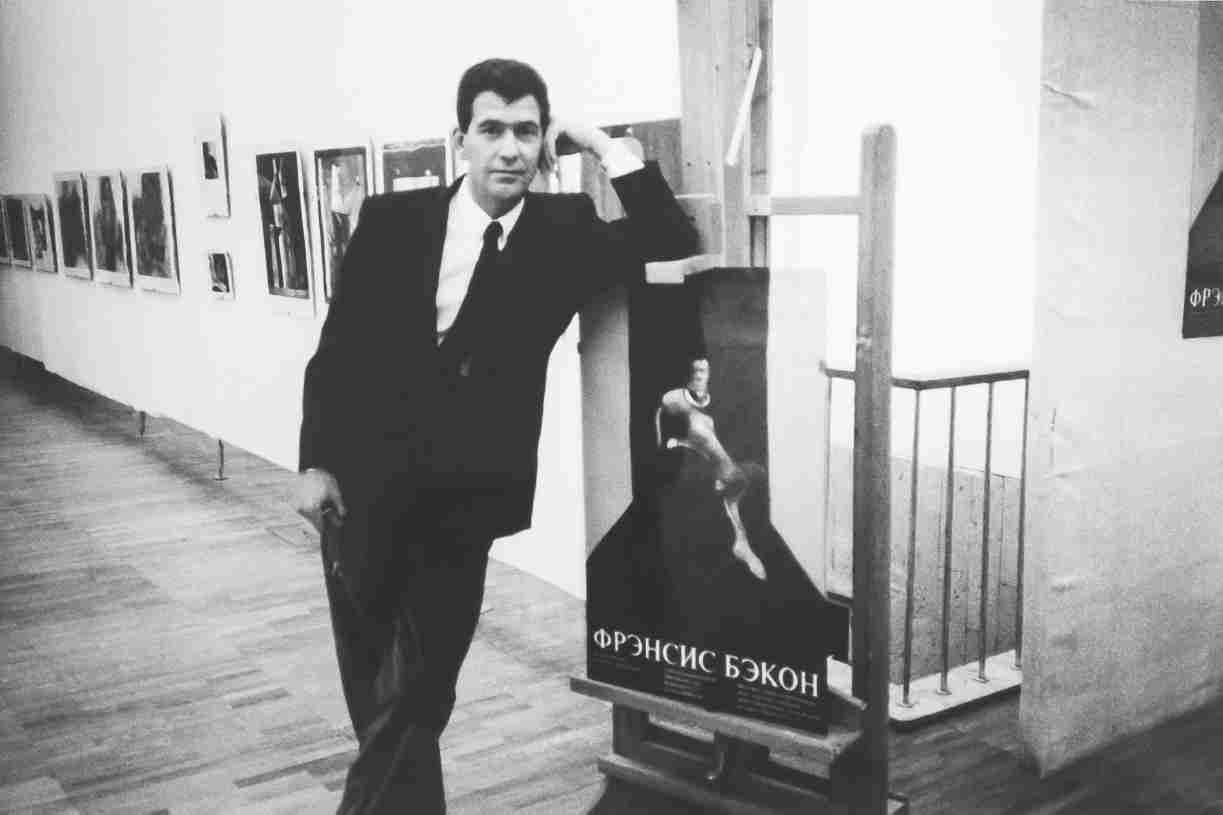

JOHN EDWARDS BY POSTER OF HIS PORTRAIT

On my last visit I had found Moscow changed ; thanks to Gorbachev those changes were being consolidated. International travel was newly available and it was much easier to apply for a visa. Huge, dynamic transformation was underway ; Soviet citizens were now free to travel the world. Free, that is, if they had connections abroad. But other things had worsened. In Moscow food was beginning to run out and basics like butter or coffee were almost impossible to obtain. When the show opened, one embittered Moscow wit would write in the visitors’ book, ‘We want bacon, not Francis Bacon.’

When I woke up the next morning, I was to discover maddeningly that I couldn’t talk to John and make the necessary arrangements to meet up because the phones were not working between our hotels.

In 1988 we didn’t have mobile phones, so for the duration of the trip if I wanted to find John I had to go and hunt for him. I assumed that both our rooms were bugged. I don’t doubt that Klokov kept a close eye on John and knew where to find him all the time. He always knew where you were and who you were there with, as I was well aware. I had explained to John that everyone we interacted with was probably reporting back everything we did.

That evening John and I met in the bar at the National Hotel. John was delighted with the appearance of his portrait on the catalogue cover.

‘Oi, James,’ he called when I walked in. ‘There are posters of me all over the shop !’

We had drinks with Bruce Bernard, William Packer from the Financial Times and art critic Charles Darwent, friends from my Soho life. Their presence in Moscow impressed the reality of the exhibition on me. We were invited to dinner in Klokov’s apartment, in the centre of Moscow. At some point, I joined him in the kitchen, where all private chats seemed to take place. There was nowhere else to go. I wanted to know what plans I would need to make to hold true to my promise to Elena.

‘It’s different now James. All you need to do is agree to sponsor her and be responsible for her and she will get a visa.’

I felt relieved. ‘Great, that’s a simpler and better option Sergei.’

The kettle began to boil. I turned and asked, ‘Shall I turn it off?’ And he said ‘No !’ Instead he just whistled, as you might whistle for a dog, and Marina came running in. It was yet another example of how Klokov wielded power in his private life as well as his public one and I found it disturbing. But there were other, more pressing matters.

Back at the table, I could see that John was deeply impressed with Klokov’s enthusiasm for, and apparent knowledge of, Francis’s work. A knowledge I noted to myself that Klokov had only recently acquired. John didn’t take a critical view of Bacon’s work but he understood his importance and was incredibly protective of his critical reputation. I could see a very instant affinity had grown between them. It was evident that Klokov’s apparent worldliness and charm, even though by now I was beginning to think it was verging on the sociopathic, had engaged John. I suspected too that he was finding his first experience of Moscow both dizzying and profoundly strange.

John asked with true innocence, ‘Why doesn’t the Pushkin Museum have a Bacon painting on display?’

‘They don’t own one,’ Klokov replied airily. ‘But if I were given one, I would leave it to the Pushkin Museum.’

I nearly laughed out loud at Klokov’s blatant self-interest but John, I think, was beguiled by Klokov and probably, as I knew from my first visit to Moscow, experiencing some kind of out-of-body moment with the strangeness of it all.

‘That’s a great idea,’ said John. I was incredulous. John, who had talked Francis out of giving me a picture and who fended off chancers again and again in London, had just offered one to Klokov on the fanciful understanding that, without guarantee, the picture would eventually be donated to a national museum. But the moment passed, we drank more vodka, and I turned to talk to Elena. If the next morning I remembered John’s promise, in the cold light of day it seemed so implausible and outlandish that I forgot about it.

I had promised Francis that I would look after John and I was true to my word. In particular, he loved GUM, the Harrods of Moscow, which had literally nothing in it. It was an in-joke between us but we spent hours trawling the aisles. My parents and some of their friends came to Moscow for the show. I was immensely touched by their support but also by their understanding that I would have to look after John rather than spend time with them. Mum, of course, was an old hand in the Soviet Union and my father was well travelled and enjoyed the general air of excitement and sociability.

John, conversely, needed guiding in everything. I started by showing him how to get around the city by holding out a packet of Marlboro cigarettes until a car gave you a lift (it wasn’t always a car, on one occasion I was picked up by the military and sat in the back with soldiers — that lift cost me a lot of cigarettes).

We saw little of Klokov, who was caught up in the to and fro around the exhibition, so we made our own way around. In Moscow the roads are wide so you can’t cross them ; you have to go under them. Going through one underpass we were stopped by a crop-haired guy with a sallow, hungry face, presumably an ‘Afghanets’. He rubbed his fingers with his thumb in the circular motion which meant did I want to exchange Western money into roubles. Neither of us had any money to change.

Then John said, ‘I’d love to get some caviar,’ and I said ‘Caviar?’, an international word of sorts. The guy said ‘Da’. John didn’t have any dollars but he did have condoms, a perennially scarce resource in Moscow, and was delighted to swap two packets for a large jar of caviar. The feeling that we were under constant observation had dropped away.

On Thursday 22 September, the opening day, I woke early and excited. The portents were good. In my bathroom the water was hot, my shower worked and, for the second time in Moscow, my eggs arrived soft-boiled at breakfast.

My luck continued outside the hotel ; within seconds of putting my hand out a car pulled up and I was on my way to collect John, once more beautifully suited and booted. When we arrived at the Central House of Artists there was a long queue outside.

John saw it and whistled, ‘Fucking hell James, I think Francis is going to be a sell-out.’

Inside we were told the queue had been forming since daybreak and the crowd’s excitement had built through the morning. It was thrilling to observe. We climbed the stairs and I was surprised to see the work of German op and installation artist Günther Ucker on show on the first floor. Amusingly, because of a national nail shortage, quite a few nails from his sculptures had gone missing. I wasn’t bothered. There would be no competition. Francis’s work would completely overshadow Günther’s.

QUEUE OUTSIDE THE CENTRAL HOUSE OF ARTISTS, MOSCOW

The first sign of unrest came later in the afternoon, but not from the queue. John and I, along with every other Western visitor to the exhibition, had been invited to the press launch. Because of Gorbachev’s anti-drunkenness drive, it had been announced that no alcoholic drinks were to be served at official functions. On hearing this, a shiver had run through the international press corps. The news of a ‘dry’ party sharpened their outlook as well as their pens, so when the press conference began at 4 p.m. they were looking for a target. Henry Meyric Hughes, Grey Gowrie and, at last, the mythical Tahir Salahov, the man I had pursued for over two years, were gathered in a reception room.

Gowrie first delivered Bacon’s apologies for not attending, explaining that he was prevented from travelling by a bad asthma attack. Bacon was, he said, ‘possibly the finest artist alive’. This was a landmark show, he explained, thirty works from 1945 to 1988 had come to Moscow, including five large triptychs and two recent works which had not been exhibited before, drawn from public and private collections in Britain and Europe. But the British press was interested in a picture that wasn’t there, the one Klokov had described so eloquently in his letter to me. Word had reached them that Tahir Salahov had rejected the Tate’s offer of one of Francis’s most important works, Triptych, from August 1972, on the grounds that it was too pornographic. The central panel of the triptych was supposed to show two men wrestling but they were clearly having sex. It was definitely what Klokov would call ‘a cock-exalting canvas’.

Why was it not here? demanded the press. Why had the Soviets censored such an important work? Was there no perestroika or glasnost for homosexuals?

In the face of these enquiries Salahov looked uncomfortable. ‘Our government has certain laws which are under review in the era of glasnost, especially concerning that category of people. I do not think this will be the last exhibition that Francis Bacon will have in Moscow. Perhaps someday, we will have another exhibition that will show other sides of his … creativity.’

Andrew Graham-Dixon, one of the British press corps, shouted out : ‘Why, if you are a homosexual, are you locked in the gulag for twenty-five years?’

‘We are interested in Francis Bacon’s art, not his private life,’ came Tahir Salahov’s reply.

Gowrie, fearful for the success of the show and a potential diplomatic incident, albeit a cultural one, smoothed the waters. No paintings had been censored, he said clearly and calmly. There was only one major painting by Bacon that could be seen as having a homosexual theme, he said.

‘As far as I know it wasn’t suggested at any stage. I suppose when human beings wrestle, if you put them on top of a bed, it is possible to interpret it sexually.’

The next day, Klokov would reveal the truth to a journalist, which was then printed in the Independent. ‘We decided to leave out the triptych, and I telephoned Francis Bacon and told him that, unfortunately, this painting might be misunderstood by the general public in the USSR. I had to explain, in the end, that what I actually meant was that it might be understood.’ He laughed. ‘But it is not such a bad thing that this picture was left out. It was very important not to give the exhibition too much the appearance of a scandal ; to include the triptych might have made conservative elements in this country dismiss the whole show, to make it an object of ridicule.’

Salahov gave a speech, the British Ambassador Sir Rodric Braithwaite gave a speech, and then more Russians gave speeches for what seemed like an agonisingly long time but was probably only a matter of minutes, after which, at last, everyone entered the big hall to see the show. I remembered that the gallery had six large rooms. I had warned Francis that the walls were slightly dirty looking. In fact, they enhanced the effect of Francis’s work, but even in my wildest dreams I hadn’t expected the paintings to look so spectacular in the slightly shabby surroundings. I was freshly astounded by his genius.

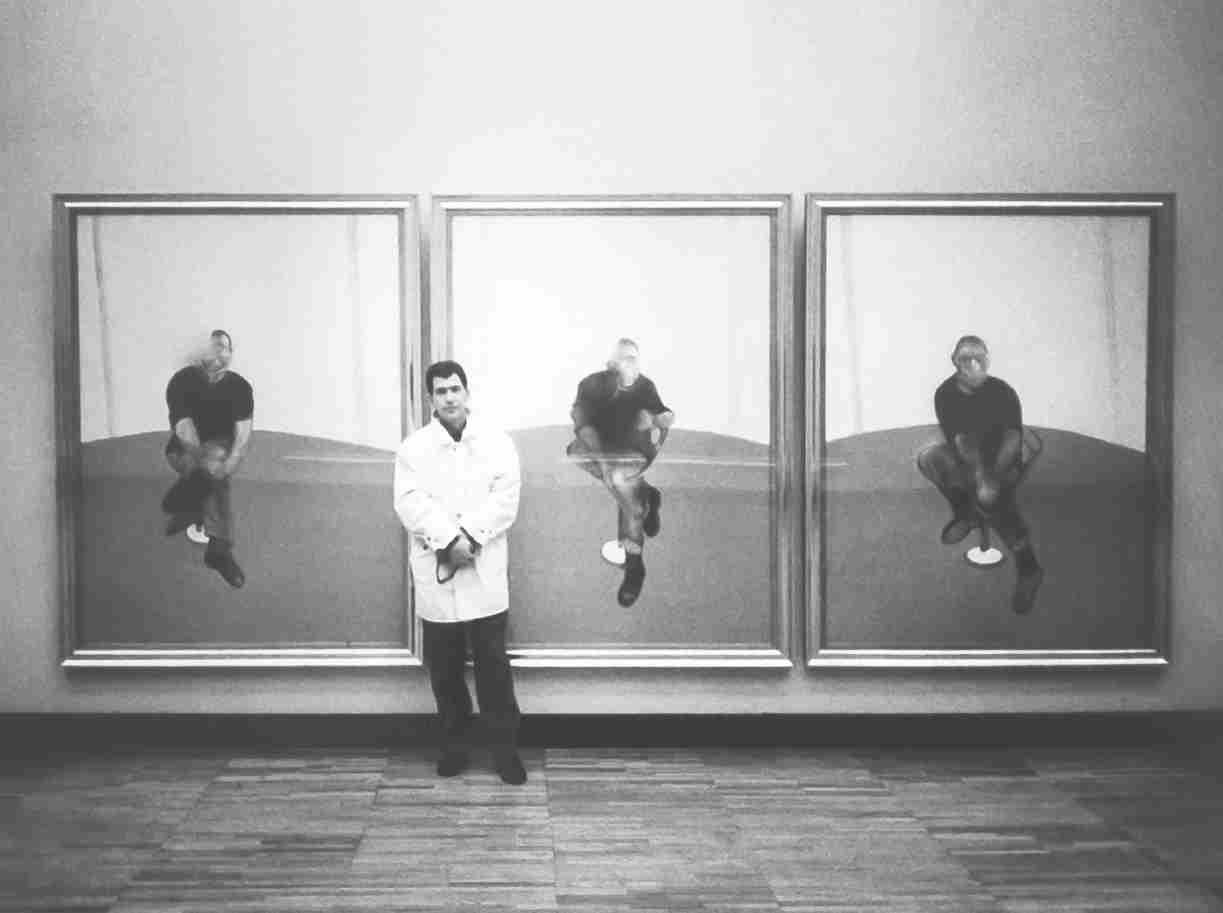

JOHN EDWARDS IN FRONT OF

“STUDY FOR SELF PORTRAIT, TRIPTYCH”, 1985-86

They had been beautifully hung by Gill Hedley and the impact of the exhibition was dramatic, much better than the Tate retrospective of 1985 which had too many pictures. Here they were properly spaced, mixing early and later works. I was freshly reminded of Francis’ choice to have Study for Portrait of John Edwards on the front of the catalogue and the exhibition posters which we kept seeing in hotels and key public places. I knew it was Francis’s tribute to John. But the overwhelming feeling was one of disbelief. The pictures were here behind the Iron Curtain. The exhibition was happening. The impossible had happened. I felt joy surge through me.

John and I had been invited to the official after-party at the Union of Artists House on Gogolevsky Boulevard. Elena, John and I jumped into a taxi as the queuing Muscovites poured in to see the show, which was open until 9 p.m. The entrance fee was only a few kopeks, which I thought was a reasonable price, but even that was a much-discussed novelty in a city where exhibitions were always free.

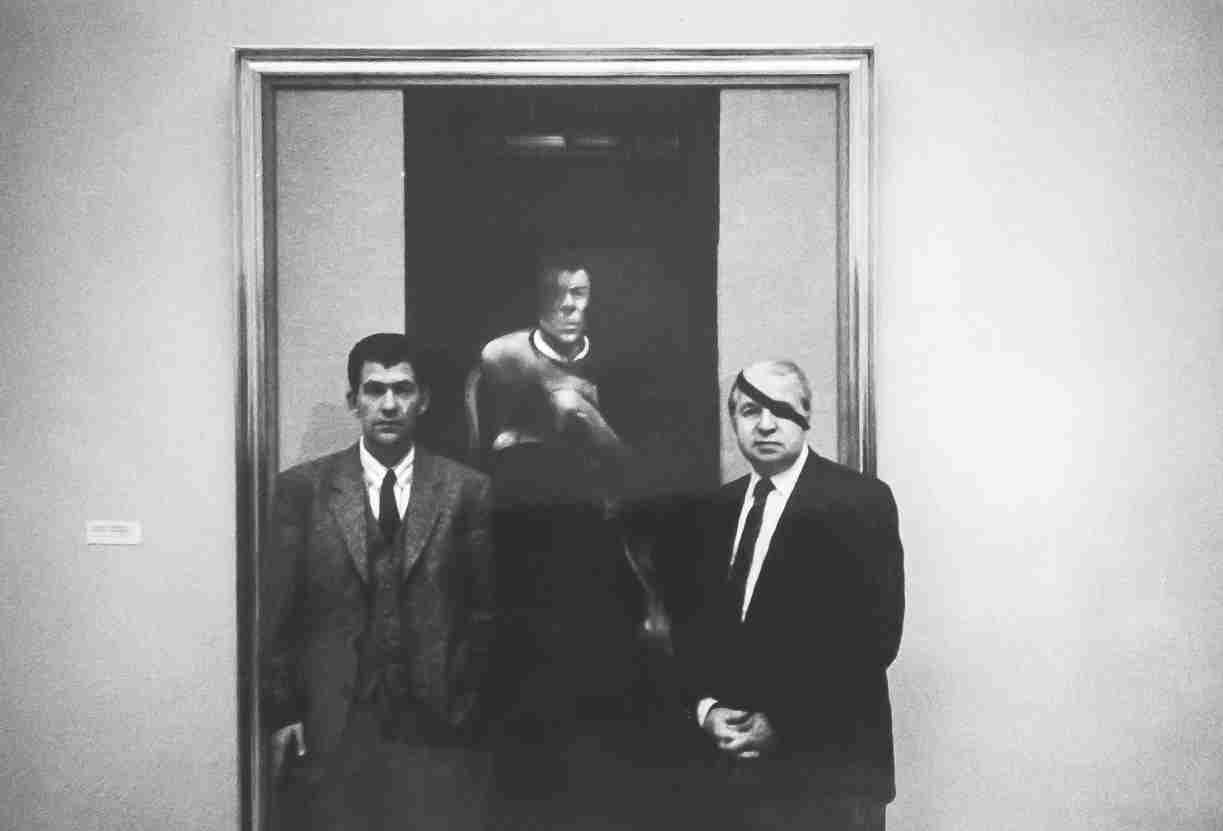

JOHN EDWARDS AND VLADIMIR ZAMKOV IN FRONT OF

“STUDY FOR A PORTRAIT OF JOHN EDWARDS”, 1988

There was not a formal dinner at the Union of Artists House. The protocol involved in deciding the seating precedence would have been beyond the Union officials. Instead there was a stand-up buffet, a line of tables laden with Soviet bounty. Outside the room people were going hungry, inside there were platters of ‘Olivye’ salad, ‘Stolichnaya’ salad, cucumber salad, celery leaves, the ubiquitous caviar, both red and black, black bread, smoked sturgeon, all kinds of cold meats. The fare was considerably better than you were likely to find in a restaurant and The Union of Artists had cleverly contrived to avoid government diktats about alcohol at official functions. Vodka and champagne flowed.

I remember feeling numb and disembodied. Looking across the room I could see British grandees, members of the Politburo, KGB agents and then John Edwards laughing with Henry Meyric Hughes. Klokov, who as ever was wearing Pierre Cardin, flitted from group to group. It was almost amusing to see him assiduously building his contacts and, no doubt, accepting the credit for the exhibition. It was, after all, his great achievement and perhaps only possible for a man with his family credentials.

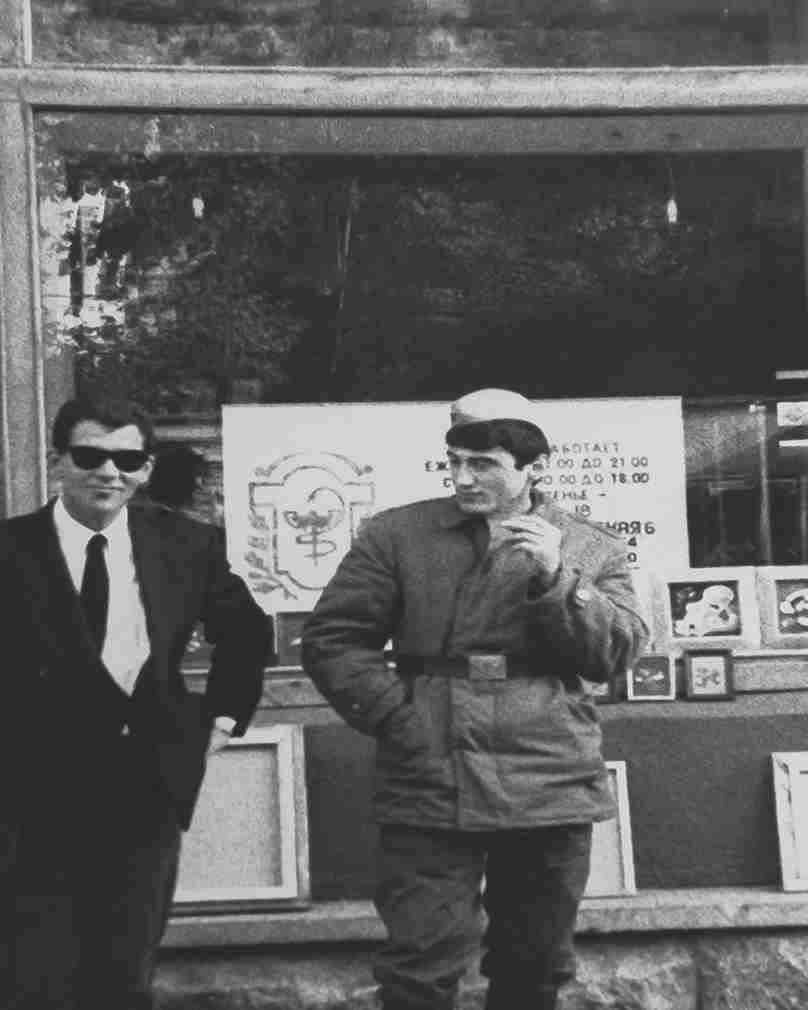

JOHN EDWARDS AND SOLDIER

I passed him as he spoke with a journalist : ‘This exhibition is only possible, administratively, morally, ideologically, at this particular moment in Soviet history,’ Klokov said. ‘Bacon paints the evil in humanity, without mercy. That is new in Russia. The exhibition is a symbol of our whole concept of perestroika — now, thanks to Gorbachev, we are not afraid to show the dark side of life, the dark side of society — of our society.’ He reached out to me, ‘Ah James, I was right all along. The queues are longer than those for Lenin’s mausoleum.’

And then there was Elena, beautiful in one of her constructivist dresses, clearly interested in and smiling at the opulence and excitement around her and chatting to Kate Braithwaite, the Ambassador’s daughter and a newfound friend, but as ever keeping her cool.

On the following day, there was a round of official engagements and meals. Sir Noel Marshall, Deputy Ambassador, gave a lunch and a few members of the UK contingent were invited.

Afterwards John and I walked back to the National. I wanted to show him Red Square and Lenin’s mausoleum but the square was closed off to the public and we were stopped by a soldier. John happened to have Sir Rodric’s card, printed in English and Russian, in his hand and, chancing my arm, I said to John, ‘Show it to the guard.’ These were new times after all. What would the soldier do? Doubt played across his forehead. In the end he relented and let us past the barrier. John and I strode to the centre of Red Square which was, for this brief moment in time, ours and ours alone.

John looked around and took it all in, the Kremlin, the onion domes of St Basil’s cathedral, the glowering block of Lenin’s mausoleum.

‘Not bad, eh James?’ He said. ‘Wait till I tell Francis about this. He’ll love it.’

On the second evening, I met up with Elena. John was elsewhere in hot pursuit of somebody with whom to wrestle on a bed. Elena and I went to Stalin’s favourite restaurant, a typical old-fashioned Georgian place near Smolensky Prospekt. The food was delicious. We had soup followed by some salad, ‘khachapuri’ — cheese-stuffed bread — yoghurt with dill and some very good Georgian wine. There were many bottles of vodka on display behind the bar, and not for the first time, I wondered just how effective the war on drink could ever be in a country so steeped in alcohol.

A passing waiter, seeing a beautiful woman apparently with her foreign lover, drew the curtains to our booth. We were alone. Elena fixed me with one of her more intense Slavic gazes and leaned across the table. I leaned towards her and our hands touched. I remained beguiled by her beauty, but I was too shy to ask her to stay the night with me. She seemed unconcerned that we no longer had to make plans to marry. The night felt enchanted. I reassured her that I would sponsor her trip and that she would come and live with me in London, and that I would love and support her.

‘I only have to sign a piece of paper Elena. Sergei says he can fix it.’

I realise now that I fell in love with the idea of a person who I had unconsciously conflated with my love affair with a country. Unbeknownst to me, relationships like these were known as ‘The Russian Bug’ in Russia. But on that particular evening, the only disconnect I could perceive was one of language, which I found charming. Any absence of shared experience, such as her revelation that during the Cuban Missile Crisis her schooling took place in a bunker, seemed a minor problem that could be overcome with time.

Elena’s face brightened.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Sergei can fix everything.’

Misha had given me an article in Russian by the well-known critic Morgova. I showed it to Elena who translated, ‘the revolutionary nature of this exhibition will open doors to more Western Art coming into the Soviet Union, and Soviet Art going to the West. It was, he said, the best and most important exhibition he had ever seen in the USSR.’ It was a triumphant moment — all the more because I had someone to share it with.

Elena lived quite far out of central Moscow, near the Kosmos Buildings. We went outside to get her a car. I held up my cigarettes to stop a driver and there in the Moscow fug of cheap petrol fumes we finally kissed. It was tentative rather than passionate and had barely begun before a battered Lada clanked up at the kerb beside us.

‘Here take these.’ I gave Elena my last two packets of Marlboro. ‘See you tomorrow.’

And with that the Lada rattled off into the night.

Klokov rang me the next morning.

‘James ! Elena wasn’t at home when I called her last night. Did she sleep with you?’

‘No,’ I replied truthfully.

I thought it was an odd question, but it was only years later that I realised that he had expected her to report back on the evening’s activities, and perhaps had been expecting more than that.

Before John returned to London, Elena, he and I spent an afternoon at the gallery, soaking up the show so we could tell Francis every last detail. We were allowed an hour in the gallery on our own — it felt incredible to have the chance to see the pictures again. It only reinforced my sense of accomplishment. The queues were even longer than the day before, and then the doors opened. It was packed within a matter of minutes. In front of each picture, a large group of Russians was looking intently at the canvas. Not glancing and moving or talking to each other like a London crowd but taking in everything that they could. There was complete silence. This time, with Elena’s help, I asked a number of people what they thought of the exhibition.

ELENA KHUDIAKOVA OUTSIDE THE EXHIBITION HALL

One man in his forties, who looked very down at heel, appeared to be transfixed by Study for Portrait of Van Gogh III, 1957.

All the clichés that were trotted out in the West, about Bacon as the painter who had uniquely responded to the horrors of war, Holocaust and coming nuclear conflagration made sense in this context, they weren’t clichés in a city where the Nazis had reached the suburbs and untold millions had died. When the Russians looked at Francis’s work they understood and they connected. My dream was made real.

A middle-aged lady said she ‘couldn’t understand it at all’ ; another woman said she ‘didn’t find it close to her art’ but was interested in Bacon’s direction. She praised ‘his energy and style’. A young soldier liked the exhibition and praised Bacon for great imagination but was a bit confused. Another man we spoke to had seen a reproduction of the Screaming Pope in a magazine and was overjoyed to see it in the flesh. A female artist believed ‘it was a very important event in the history of the Soviet Union’.

Perhaps I had not anticipated how overwhelmed I would feel hearing people’s powerful responses to Francis’s work. It made the highs and lows and the dreadful anxiety feel worthwhile. People didn’t connect the portrait of John with John in the flesh. But I could tell that even he, despite his apparent cockney insouciance, was excited by people’s reactions and was genuinely delighted on Francis’s behalf.

JOHN EDWARDS IN A GALLERY EMPTY OF PEOPLE

And I was grateful, more than I could admit to myself, for Elena’s companionship and help on this trip. It seemed to bode well.

Much later, perhaps four hours later, I went to leave the exhibition. On my way I passed the man in ragged clothes, still looking at Study for Portrait of Van Gogh III, 1957. He hadn’t moved.