Although the Beats are best known as writers and poets, they had a broader identity as bohemians bent on challenging the folkways and mores of their time. “Bohemian” in this sense derives from a French usage referring to gypsies, who were thought to come from Bohemia when they arrived in Western Europe half a millennium ago.

The term “bohemian” acquired its more modern meaning in the nineteenth century, when Henri Murger wrote stories about “La Vie de Bohème,” centering on colorfully poor artists, writers, and poets. These tales inspired Giacomo Puccini’s 1896 opera La Bohème, which improved the term’s international credentials. Bohemianism entered the English language thanks to William Makepeace Thackeray, who described the heroine of his 1848 novel Vanity Fair as having “a wild, roving nature, inherited from father and mother, who were both Bohemians, by taste and circumstances.” All this is encapsulated in the Oxford English Dictionary definition most relevant for our purposes: “A gipsy of society; one who either cuts himself off, or is by his habits cut off, from society for which he is otherwise fitted; especially an artist, literary man, or actor, who leads a free, vagabond, or irregular life, not being particular as to the society he frequents, and despising conventionalities generally.”

Jack Kerouac invented the Beat Generation’s name. This is not surprising, since he used the word “beat” often—describing the melancholy heroine of his 1960 novel Tristessa, for instance, as “frail, beat, final.” But the word has a longer history. Some scholars date it to the Civil War era, when it meant “a lazy man or a shirk,” and the Beat historian Ann Charters traces its modern usage to the 1940s, when hustlers and musicians used it to mean poor, exhausted, or down and out, as when jazz musician Mezz Mezzrow wrote about “a beat-up old tuxedo with holes in the pants” and said, “I was dead beat.” Ginsberg felt the word had many different meanings, including “exhausted, at the bottom of the world, looking up or out, sleepless” and “wide-eyed, perceptive, rejected by society, on your own, streetwise.” Kerouac associated “beat” with his streetwise friend Herbert Huncke, a Times Square grifter who “appeared to us and said ‘I’m beat’ with radiant light shining out of his despairing eyes … a word perhaps brought from some midwest carnival or junk cafeteria.”

Kerouac gave the term its most enduring meanings. As early as his first novel, The Town and the City, he described a character “wandering ‘beat’ around the city,” searching for moral and financial support. At times he found negative meanings in the word, as in Desolation Angels, where he says the word implies “mind-your-own-business,” as in “beat it,” and in a 1959 essay where he wrote that “beat” means “poor … deadbeat, on the bum, sad, sleeping in subways.” At other times Kerouac did not seem quite sure what it meant, as when he gave the definition “sympathetic” on Steve Allen’s popular television show. But usually he gave the term positive implications, writing in 1958 that after the Korean War of the early 1950s, young people came out “cool and beat … and the Beat Generation, though dead, was resurrected and justified.” Ultimately, favorable and even mystical meanings prevailed in Kerouac’s mind. This is clear in On the Road, where the narrator (a stand-in for the author) says of Dean Moriarty, the character based on Neal Cassady, that he “was BEAT—the root, the soul of Beatific.”

For many people, Beat and beatnik are synonyms. But experts on the subject think otherwise. While the term “beat” came from hustlers, jazzmen, and authentic Beat writers, the word “beatnik” came from a journalist, Herb Caen. He wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle, and in 1958 he cobbled the term together from Beat Generation and Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to go into orbit, launched by the Soviet Union a year earlier. Discussing the neologism later, Caen claimed that he invented it to poke fun at the Beats because they took themselves too seriously. It caught on so quickly that even Caen was amazed: His newspaper ran a headline about a “beatnik murder” the day after he first used it. The new word angered real Beats, including Kerouac, who said to the columnist, “You’re putting us down and making us sound like jerks. I hate it. Stop using it.” Caen obviously did not.

The idea of finding a New Vision, and accomplishing this through new forms of art, came early in the Beat saga. The first ones to pursue it were Allen Ginsberg and Lucien Carr at Columbia University in the middle 1940s, and it was a major discussion topic when Ginsberg and Kerouac got together for serious talks. A problem arose, however: nobody was quite clear about what the New Vision was supposed to be. The words obviously imply a fresh way of seeing, or an unprecedented and “visionary” way of encountering the world, but this is still vague. The unanswered question is how one would acquire the kind of “vision” that Aldous Huxley discussed in his 1954 book The Doors of Perception, which borrowed its title from the great Beat icon William Blake: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

One answer was travel, done in the frenetic and far-reaching Beat style. Another involved what the French poet Arthur Rimbaud called the “long, prodigious, and rational disordering of all the senses,” allowing sensory inputs to function and commingle in unusual and exciting ways, often with the aid of drugs. A third possible route to new vision is the creation of revolutionary artworks, such as the explosive James Joyce novels (Ulysses, Finnegans Wake) that Ginsberg and Kerouac admired. Beats experimented with these and other possibilities, mindful that even their best creative ideas were in a constant state of flux, flow, and evolution. After their early enthusiasm for “new vision,” they turned to other expressive terms—“eyeball kicks,” “spontaneous bop prosody”—that articulated their desire to subvert postwar paradigms through artistic experimentation. Some brought political action into the mix as well, although others, especially Kerouac, considered this alienating and unproductive. “Issues,” he once said. “Fuck issues.” For him, revolution from within was the only kind of revolution that counted.

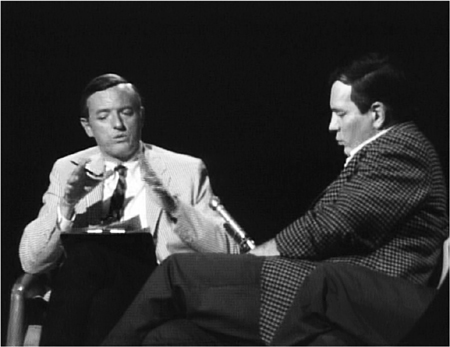

2. Jack Kerouac’s political views were more conservative than those of many other Beats, but his words during a 1968 appearance on Firing Line, the long-running TV show created and hosted by the very conservative William F. Buckley Jr., were closer to free-form rambling than social commentary.

This said, though, all of the Beats wanted to challenge the social givens of their day. In their minds, modern society was crisscrossed with insidious networks of malignant forces designed to cage, manipulate, and smother the otherwise free spirits that are God’s gift to each of us. Burroughs called the enemy “the control machine,” defining it as “simply the machinery—police, education, etc.—used by a group in power to keep itself in power and extend its power.” These mechanisms produce lowered levels of consciousness, not the raised consciousness that might improve the human condition.

Politically speaking, Kerouac embraced notions far to the right of Burroughs’s ideas, but he agreed about the basics. In his 1954 story “cityCityCITY” he sketched a picture of conformity as frightening as the one in Huxley’s prescient 1932 novel Brave New World, showing a population controlled and regimented by mass-media Multivision along with computers, tranquilizers, and a surgical process called “Deactivation” that produces “general psychic pacification.” The specter of suburban sameness was still with Kerouac when he wrote The Dharma Bums three years later, describing

house after house on both sides of the street each with the lamplight of the living room, shining golden, and inside the little blue square of the television, each living family riveting its attention on probably one show; nobody talking; silence in the yards; dogs barking at you because you pass on human feet instead of on wheels. You’ll see what I mean, when it begins to appear like everybody in the world is soon going to be thinking the same way.… I see [Gary Snyder] in future years … his thoughts the only thoughts not electrified to the Master Switch.

Ginsberg was also alarmed about modernity’s dehumanizing trends. He embodied them in the false god Moloch that looms terrifyingly large in “Howl,” and he attacked them often in other works—when he wrote, for example, that “among the abundance and the affluence … among the automobiles, the televisions, the household appliances, the hi-fi-sets, the fallout shelters, the SAC bombers, and the nuclear missiles, we [have] misplaced or displaced ‘the lost America of love.’”

For the Beats, raising consciousness and attacking repression were two sides of the same iconoclastic coin. Although the phrase “new vision” gradually fell into disuse, the ideals it represented stayed alive, compelling Beats to bypass society’s well-traveled roads via Buddhism, bebop, mind-expanding drugs, and fresh approaches to what Kerouac called the “humankind materials of art.” And this is why the best Beat writers questioned the nature and purposes of writing itself. Burroughs, for instance, was not just an anticonformist author but, in some ways, an antilanguage author who knew the power of words to enchain and to liberate, depending on how they are used. Words are “the principal instruments of control,” he insisted. “Suggestions are words. Persuasions are words. Orders are words.” How can we protect ourselves against their ill effects? “Prisoner, come out,” says a character in The Soft Machine. “The great skies are open … rub out the word forever.” Burroughs attacked language’s control machine by cutting it up and folding it over, transforming texts into collages that celebrate the anarchic freedoms of the irrational unconscious mind.

Ginsberg too saw the danger of words turned into weapons by power-driven manipulators. Writing in 1961, he identified three elements in his own experience—“intervals of tranquility,” psychedelic drugs, and “changes of life and personal crises”—that allowed him to tap “vastnesses of consciousness in which all I know and plan is annihilated by awareness of hidden beingness.” He added that “all creation and poesy as transmission of the message of eternity is sacred and must be free of any rational restrictiveness; because consciousness has no limitations.” Ginsberg found that “all diverse simultaneous impressions and events [can] focus together to make a new, almost a mutant, consciousness.” This induced him to aim for higher things than instrumental logic and its commonsense conclusions. “[I]t is good to be able to say that I never in advance really know what I’m going to write,” he revealed, “if the writing is to become anywhere near sublime. That’s that.” Ginsberg’s writing philosophy of “first thought best thought” reflects the same set of convictions.

Kerouac also believed in “first thought best thought” writing as a means of evading the restrictions and limitations of literarily correct communication. The same impulse led him to draw strongly on the sense-defying flights of Buddhist meditation and his jazz-inflected rhythms in his prose and poetry. Kerouac got attuned to “the sound of the language,” as Ginsberg put it, “and got swimming in the seas of sound and guided his intellect on sound, rather than on dictionary associations with the meanings of the sounds. In other words … another kind of reason.… If you can use the word reason for that.” You cannot, and that is the point. Raising consciousness beyond consciousness while attacking every kind of repression—those were the points behind the point.

“The essence of the phrase ‘beat generation’ can be found in [a] celebrated phrase, ‘Everything belongs to me because I am poor.’” So said Allen Ginsberg in 1981. He misremembered Kerouac’s words as coming from On the Road, whereas they really appear in Visions of Cody and also in a 1959 article called “The Beginning of Bop” that Kerouac wrote for Cavalier, a men’s magazine. The phrase was much on Kerouac’s mind in the 1950s, and in Visions of Cody, published in 1960 but written almost a decade earlier, the words have deep and rich significance. Jack Duluoz, the surrogate for Kerouac in the novel, has been watching and daydreaming about a “pretty brunette with violet eyes” as she eats a meal. She is reading a Modern Library book, which makes her even more attractive, “maybe a hip young intellectual girl” who is just his type. “She’d melt for me in two minutes,” Duluoz muses, but then, “beautifully, with simplicity,” she leaves. The passage ends,

It no longer makes me cry and die and tear myself to see her go because everything goes away from me like that now—girls, visions, anything, just in the same way and forever and I accept lostness forever.

Everything belongs to me because I am poor.

Here as elsewhere, the poverty Kerouac welcomes has less to do with possessions than with spiritual values. In the past, Duluoz tells us, he would have been actively miserable at the departure of a romantic reverie, and of the woman whose beauty and manner touched it off. But by this stage in his still-young life, he has grown resigned to disappearances—of the women who have filled his dreams, the visions that have filled his imagination, and indeed everything in the wide world that enfolds him. And his resignation is rooted in wisdom. Although persons and possessions may elude him, all of America and the great spaces beyond it are within his grasp, any time he chooses to rush off and embrace them. On the surface, Duluoz is accepting “lostness” as readily as he’d welcome an old friend. On a deeper level, Kerouac is starting to live out principles of Buddhism that played an increasingly large role in his intellectual and spiritual life. More specifically, he’s acknowledging what Buddhism calls the “impermanence” of the human condition.

Kerouac was no dilettante or dabbler in Buddhist doctrine. According to Ginsberg, who was passionate about this subject, Kerouac grew to be a “brilliant intuitive Buddhist scholar” who grasped the slippery notion that “this universe is real, and at the same time unreal … form and emptiness are identical.” If reality and unreality are the same thing, then being poor and owning everything are the same thing, and there is nothing to regret when things prove transitory. Or as Kerouac put it in Mexico City Blues, an epic poem shot through with Buddhist thinking, “Bring on the single teaching … Love of Objectlessness.”

Not everyone agrees about the depth of Kerouac’s Buddhist awareness. The Beat poet Philip Whalen said his friend’s interest in Buddhism was more literary than religious, and even Ginsberg wrote that as Kerouac grew older, “in despair and lacking the means to calm his mind and let go of the suffering, he tended more and more to grasp at the Cross … finally conceiving of himself as being crucified.” It is true that Kerouac was, in the end, more a Roman Catholic than anything else; even in the novel Desolation Angels, which has strong Buddhist resonances, he calls Buddha his “hero” but immediately adds, “my other hero, Christ is first.” Yet there is no real contradiction here, since in both religions what Kerouac sought was transcendence, a sense of refuge from the barely controlled turbulence of his inner world. This is most vividly evoked near the end of the 1962 novel Big Sur, where a night of hallucinations and delirium, brought on by alcohol withdrawal, culminates in a profoundly Christian vision: “I see the Cross, it’s silent, it stays a long time, my heart goes out to it, my whole body fades away to it.” If the ultimate in “poor” for Kerouac was to lack even the alcohol he loved, he could still find “everything” in mystical faith.

Kerouac’s use of the word “poor” also has an earthbound sense, linked to rejection of materialism in general and 1950s consumerism in particular. He and the other Beats agreed that lusts for money and power are perhaps the deadliest human pitfalls. Americans often give up what they really need, Kerouac wrote in his journal, “for the sake of some golden automobile.” This and similar concerns arose partly from the Beats’ interest in the Transcendentalist school of American writing, epitomized by Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and partly from the joys they themselves found in simple, inexpensive pleasures—love, sex, drugs, travel on the cheap—during their inner and outer journeys. They could be tempted by material comfort, but they were suspicious of it as a final goal, so it is not surprising that Kerouac, Ginsberg, Whalen, and Gary Snyder were drawn so strongly to Buddhism, even if some of them blended Buddhist concepts with other religious ideas, as Kerouac did with Christianity and Snyder with American Indian mythology.

Even the skeptical-of-everything Burroughs created a literary mythos that draws on an array of religious, folkloric, and supernatural belief systems.

Most of the core Beats earned enough from writing, speaking, teaching, and other such activities to live decently during most (if not all) of their lives, but at their best they exemplified the poor in spirit whom Kerouac’s most basic faith, Christianity, claims will inherit the earth. Poverty is what allowed them to own everything worth owning.

One of Beat history’s most festive and decisive milestones took place in autumn 1955. A modest announcement was mailed out to publicize it:

Philip Lamantia reading mss. of late John Hoffman—Mike McClure, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder & Phil Whalen—all sharp new straightforward writing—remarkable collection of angels on one stage reading their poetry. No charge, small collection for wine, and postcards. Charming event.

The show will take place at the 6 Gallery on Fillmore Street in “San Fran,” the notice adds, and Kenneth Rexroth will be master of ceremonies. As things turned out, the reading by those “angels” gave fresh energy and lasting impetus to a pair of interrelated cultural collectives: the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance. It also made history by marking the first time that Ginsberg read a portion of his masterwork “Howl” in public.

Most people in the 1950s associated the Beat group with Manhattan’s downtown Greenwich Village neighborhood, but in fact its members were elsewhere more often than not. Sometimes they were exploring the drugs, culture, and kicks of some foreign land. Within the United States they were often on the road, and the fabled city of San Francisco ranked with their favorite haunts. It held the double fascination of being both utterly American and as far away from East Coast traditionalism as you could get without crossing (or falling into) the Pacific Ocean. It also had a long history of radicalism, bohemianism, progressive politics, and poetic experimentation, which made it a fertile and productive site for the evolution of the Beat aesthetic.

3. This image from the docudrama Howl shows Allen Ginsberg (James Franco) reading Part I of “Howl” at the 6 Gallery, an event that helped launch the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance in October 1955. By reconstructing the gallery event and the 1957 obscenity trial of “Howl” in cinematic terms, this film captures the poem’s literary and sociological importance in ways to which subsequent generations can readily relate.

San Francisco’s main Beat enclave was “the Beach,” as locals called the North Beach area. Like the Village, this was an ethnic neighborhood with relatively inexpensive housing, food, and taverns; and, like the Village, it was near a Chinatown district containing bookstores, restaurants, and other establishments tied to Eastern cultures. Two reputable poets, Rexroth and Robert Duncan, were involved with poetry-centered salons, which were beginning to spark a San Francisco Renaissance when Kerouac and Burroughs hit the city in 1952, followed by Ginsberg two years later.

They and other Beats frequented a place called the Place, which was a bar featuring a Blabbermouth Night of improv every week. They also liked the Coffee Gallery, which presented more conventional poetry readings, and the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, whose name would have seemed improbable, if not inscrutable, in almost any other city. In such places jazz, art exhibitions, and oral poetry thrived. So did stunts and gimmicks, as when an arts-friendly entrepreneur named Henri Lenoir peddled “beatnik kits” to tourists and hired a central-casting beatnik to knock off abstract “masterpieces” in the window of Vesuvio’s bar. More serious businesses included the City Lights bookstore, which opened in 1953, and City Lights Publishing, launched in 1955—venues that took on legendary status as the base of operations for Lawrence Ferlinghetti and unofficial clearing house for Beat writing in particular and postwar avant-garde literature in general. So much was happening in the city by 1957 that the cutting-edge Evergreen Review published a San Francisco Scene issue.

And there was the 6 Gallery, set up in 1954 by a group of local poets and artists who believed that poetry, performance, and visual art should be partners, not competitors. Kerouac and others have identified the October 1955 reading there as the official beginning of the San Francisco Renaissance, and it is a credible claim, although a long list of substantial poets—including Duncan, Kenneth Patchen, James Broughton, and Jack Spicer—had been living, working, and writing in San Fran for many years.

The event’s prime movers were Rexroth and Ginsberg, with Ginsberg doing the most to organize it and line up the readers. The program took shape in a sort of chain reaction: Rexroth suggested Snyder, and Snyder suggested Philip Whalen, and Michael McClure, one of the first people involved in the plan, stood ready for action when needed. Where was Kerouac in all this? He had just breezed into town from Mexico, where he had written his epic poem Mexico City Blues that summer. Ginsberg asked him to participate, but Kerouac turned him down, saying he was too bashful to read before a large audience. And large it promised to be, since Ginsberg was sending out more than a hundred postcards to spread the word. No such timidity stopped Whalen or Snyder, even though neither of them had read in public before.

Kerouac stayed on the sidelines, but he gave a colorful account of the evening in The Dharma Bums. “It was a mad night,” he wrote. “And I was the one who got things jumping by going around collecting dimes and quarters from the rather stiff audience standing around in the gallery and coming back with three huge gallon jugs of California Burgundy and getting them all piffed so that by eleven o’clock when [Ginsberg] was reading his, wailing his poem ‘Wail’ drunk with arms outspread everybody was yelling ‘Go! Go! Go!’ (like a jam session) and old [Rexroth] the father of the Frisco poetry scene was wiping his tears in gladness.” By half past eleven, he continues, “all the poems were read and everybody was milling around wondering what had happened and what would come next in American poetry.” Kerouac’s report is thinly fictionalized, but it is accurate, right down to his own role in the event. He may have been too shy to read, but he was not a shrinking violet on the margins of the evening.

Roughly a hundred and fifty people were in the gallery, including Neal Cassady and Natalie Jackson, his girlfriend at the time. John Hoffman, the poet whose work Philip Lamantia read, was known only to insiders; he had recently died at age twenty-one in Mexico, from either polio or, according to Kerouac, “too much peyote in Chihuahua.” Like Lamantia, he had inclined strongly to Surrealist verse. McClure, who followed Lamantia at the podium, drew on Surrealist thinking as well, along with Dadaist ideas and Antonin Artaud’s radical Theatre of Cruelty aesthetic. Artaud’s work inspired McClure to write “Point Lobos: Animism,” which he read at the 6, following it with verses praising the sanctity of nature. Whalen then lightened the mood with lively Zen-inspired poetry.

After intermission, Ginsberg unveiled his masterpiece “Howl,” reading only the first section, since he was still working on the rest. This was the poem that elicited Kerouac’s most energetic cheerleading, and by all accounts the rest of the audience was equally moved; so was Ginsberg, who wept with emotion as listeners hollered their approval at the end. Snyder then read “A Berry Feast,” which salutes a Native American trickster character, and selections from Myths & Texts, which would be published in 1960. After the reading, the poets and their pals “drove in several cars to Chinatown for a big fabulous dinner … yelling conversation in the middle of the night,” to quote The Dharma Bums.

Snyder and Whalen found the evening a perfect platform for their public-reading debuts, and Kerouac got a great episode for The Dharma Bums out of it. But the biggest beneficiary was Ginsberg, who had feared that “Howl” was too insular and idiosyncratic for other people to make sense of. The next day a telegram arrived from City Lights proprietor Lawrence Ferlinghetti, paying a compliment that helped launch Ginsberg as a major poet. “I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” Ferlinghetti wrote, echoing Ralph Waldo Emerson’s salute to Walt Whitman when Leaves of Grass was published exactly a hundred years earlier. “When do I get the manuscript?” Ginsberg got to work, and Howl and Other Poems appeared in 1956 under the City Lights Pocket Poets imprint.

Rewards from the charming event, which had a repeat performance at Town Hall Theater in Berkeley the following year, flowed to San Francisco’s literary scene as a whole, giving poets a freshly energized audience for their readings. “It succeeded beyond our wildest thoughts,” Snyder recalled. “In fact, we weren’t even thinking of success; we were just trying to invite some friends and potential friends.… Poetry suddenly seemed useful.” It certainly did. The reading helped crystallize a sense of community and coterie among the Beats and likeminded bohemian and avant-garde writers, and solidified the importance of oral performance as a key ingredient of the Beat aesthetic. Neither poetry nor galleries, cafés, and coffeehouses were quite the same afterward.