Beats and Beatniks were very much in the public eye during the 1950s and early 1960s. In fact, their fame far exceeded their numbers. Everyone knew about them, and many people found them scary—which is interesting, since at any given time there were not more than a few thousand of them across the country, and only a handful managed to reach a significant audience via prose or poetry. Fewer than 10 percent of them (one hundred and fifty or so) ever published any writing at all. But none of this stopped a mass-media juggernaut from exploiting the widespread interest in Beat people, places, and products.

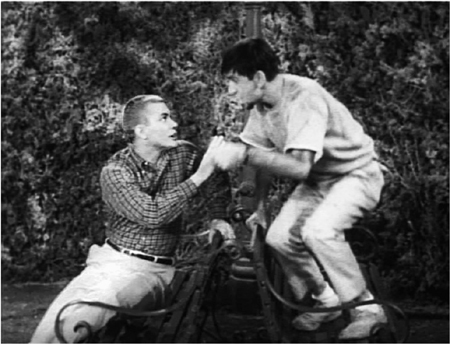

Today, as in the 1950s, impressions of the Beat Generation generally come from movies like A Bucket of Blood, the 1959 horror yarn about a loony coffeehouse artist, or vintage TV shows like The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, where the hero’s beatnik friend, Maynard G. Krebs, slouches lovably around in a ragged sweatshirt and scraggly goatee. More recent pop-culture productions paint the same sort of picture—John Waters’s 1998 movie Hairspray, for instance, where beatniks wear nothing but black as they daub their paints and beat their bongos. It is hard to banish those images, but they are exaggerations at best and outright wrong at worst. The most genuine Beats did not look or dress like Beats, since the stereotypes embraced by squares were what they were trying to escape. And only a minority were bearded. Simple clothing was the rule, “in an ordinary working-class manner, distinctive only to middle-class eyes,” a sociologist wrote.

The best-known Beats dressed in various ways. Allen Ginsberg let his hair grow shaggy (around his balding dome) and sprouted a bristly beard. By contrast, the famously handsome Jack Kerouac usually looked like a working man on vacation, with neatly combed hair and quietly conventional shirts and pants. William S. Burroughs, the writer of the most outrageous prose, was the nattiest dresser of them all, sporting well-tailored suits and a crisply cropped hairdo.

8. Maynard G. Krebs, played by Bob Denver (right), became the most famous pop-culture beatnik of his day on the television sitcom The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, in which the title character (Dwayne Hickman, left ) was his clean-cut best friend. The show aired on CBS from 1959 to 1963.

Inevitably, the Beat look(s) changed over the years. Ginsberg grew scruffier and scruffier through the 1960s, but he became more clean-cut as he aged and grew more committed to college teaching. Kerouac grew less and less concerned with his appearance as he sank into alcoholic decline. Burroughs stuck with his suits, eventually looking more like a responsible senior citizen than the iconoclastic rebel he remained at heart. If a Beat look ever really existed, it did not outlive the early flowering of the Beat literary movement.

The idea of personal transformation led the Beats to dwell in places where mainstream surroundings would not weigh on them too much. New York was the official or unofficial headquarters for almost everything in the 1950s, but it attracted Beats precisely because its hugeness offered the possibility of slipping anonymously through the cracks of ordinary society. In that spirit, the Beats moved frequently from one Manhattan location to another, from the Columbia and Times Square neighborhoods to Harlem and the Lower East Side, with sojourns in Brooklyn and the Bronx along the way.

Although the Beats will always be associated with Greenwich Village, they didn’t spend much time there. The area had been gentrified and commercialized by the early 1940s, and its bygone bohemian scenes—with anarchists at the beginning of the century, unconventional authors in the World War I era—had faded. For most Beats the Village was a stomping ground, not the stomping ground that legends portray. Especially magnetic for them was the twenty-four-hour-a-day bustle of Times Square’s sidewalks, cafeterias, and automats, a milieu that was seedier, more sensational, much less corporate, and a lot more fun than it is today.

One of the Beat Generation’s key inspirations was the rise of modern jazz. This happened in the 1940s and 1950s, when the Beats were still young and on the lookout for models to follow and ideals to achieve.

Jazz had its origins in earlier periods of American history, when marginalized people—poor folks, black folks, ghetto folks—sought to express themselves musically without having a formal education or even knowing how to read music. New Orleans spawned the Dixieland style, full of interweaving melodies, while Chicago, the Mississippi Delta, and Kansas City gave birth to the blues. In the years before and during World War II, jazz was co-opted by professional white musicians who merged it with styles of European composition. The result was swing or “big band” jazz, played by large ensembles instead of small-scale groups and combos. Big bands played from written-down arrangements, known as charts. These allowed spaces for individual soloists to improvise their own riffs, but the ensemble as a whole had to follow the chart, or musical chaos would ensue. While swing could be lively and imaginative, personal creativity suffered. And personal creativity was—or had been—the point of jazz.

This problem was solved by a new kind of jazz: “bop” or “bebop,” named after its syncopated rhythms. For example, in Dizzy Gillespie’s classic tune “Salt Peanuts,” the accents in “salt peanuts, salt peanuts” fall on the off-center bebop beats. Audiences were slow to embrace bop, and even some jazz greats found it puzzling at first; the bandleader Cab Calloway said it sounded like Chinese music to him. But many jazz artists were excited by the opportunity it gave them to leave big bands and return to small, intimate combos.

The biggest advantage of small-combo jazz was the space it opened up for everyone to improvise at any time. Bop pieces were often organized around the chords, and sometimes the melody, of a popular song that everybody in the group—and most people in the audience—already knew, providing a basic structure for improvisations that could then sprout, flower, and exfoliate in all directions. The next development was “free” or “outside” jazz that dispensed with prearranged chord progressions so soloists could do anything and everything that popped into their musical minds. Unfettered spontaneity was the key to bebop and its progeny.

All of the Beats enjoyed jazz, but Kerouac was the most messianic in this department, employing the practices Ginsberg characterized as “spontaneous bop prosody” to reproduce the spirit of modern jazz in written words. His legendary ventures in extemporaneous writing had their direct origin not only in his love of off-the-cuff invention but also in his bold notion that writers should not—and should not be expected to—stop, revise, or correct their words any more than jazz improvisers stop to correct their notes on a bandstand or nightclub stage.

Ginsberg was less obsessed with jazz, but his long-line poetry, from “Howl” to “Plutonian Ode” and beyond, owes much to the expansive improvisations of jazz musicians, especially the sax players he admired. Burroughs’s cut-up and fold-in procedures echo the changes bop artists work on familiar songs, although in Burroughs’s case—especially in radical novels like The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded—the nonlinear end product seems more similar to “outside” jazz, soaring free of any grounding at all.

Along with improvisation, the Beats loved the quotation and allusiveness of bop, which allowed musicians not only to recycle chord structures but even to drop in recognizable tunes from famous hits, sometimes as heartfelt tributes, other times as musical jokes. Ginsberg’s poetry alludes to all sorts of things, from childhood memories to religious texts and animal sounds. Burroughs’s work also wanders into unexpected places—his own life experiences in Queer and Junkie, for instance, and vividly imagined nightmares in his more ambitious (and more relentlessly weird) novels. But again, Kerouac set the pace. An example is Doctor Sax: Faust Part Three, which incorporates everything from straight-on storytelling and freewheeling poetry to childhood fantasies, journalistic headlines, bits of scripted dialogue, a tale-within-a-tale, and scenes from a “gloomy bookmovie” based on his early life. Similar jazzlike currents surge through the novel Visions of Cody and the poetry epic Mexico City Blues.

Kerouac aside, nobody expresses the Beat passion for jazz more vividly than John Clellon Holmes does in his novel Go, where he writes that in the modern jazz of the 1940s young people heard not just music but “an attitude toward life, a way of walking, a language and a costume; and these introverted kids (emotional outcasts of a war they had been too young to join, or in which they had lost their innocence), who had never belonged anywhere before, now felt somewhere at last.”

Since they appeal to the eye and ear at once, motion pictures were a natural source of enjoyment for Beats hooked on blowing, sketching, and other writing techniques that draw on keen responsiveness to sights and sounds. Sure enough, all of the core Beats were movie fans. “Movies afford me great pleasure and are about the only relief from boredom which seems to hang around me like a shadow,” wrote the eleven-year-old Ginsberg in his diary. Burroughs, who theorized that an insidious “reality film” controls our lives, said screenplay techniques influenced his conviction that being able “to think in concrete visual terms is almost essential to a writer.” Beats even dreamed occasionally of making their own films, creating Hollywood magic that would somehow be free of Hollywood commercialism. Kerouac thought about making a picture featuring his friends as both fictional characters and real-life people. Ginsberg fantasized about producing “Burroughs on Earth,” a Buddhist science-fiction film.

Only one movie—the short Pull My Daisy, directed in 1959 by the photographer Robert Frank and the painter Alfred Leslie—can be called a true Beat film, since it was narrated by Kerouac and features Ginsberg and other Beats in the cast. Another film of 1959 is informed but not dominated by Beat sensibilities: the extraordinary Shadows, directed and written—not improvised, despite a misleading sentence in the final credits—by John Cassavetes, who was just beginning his audacious career as a maverick anti-Hollywood filmmaker. But movies exploiting the Beats were more common. Audiences were fascinated when melodramas like Laslo Benedek’s The Wild One (1953) and Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955) made disciplined actors like Marlon Brando and James Dean into symbols of an anarchic generation ready to revolt against everything around. “What’re you rebelling against, Johnny?” asks nice girl Mildred in The Wild One, to which the tough-guy biker replies, “Whaddya got?” That does not sound like earthshaking behavior now, but it was controversial enough to keep The Wild One banned in Britain until the late 1960s. Kerouac’s novel The Subterraneans became a film in 1960, starring George Peppard as Leo Percepied, the Kerouac surrogate, and the French actress Leslie Caron as Mardou Fox, a black woman in the novel but a white woman in the movie—a transformation wrought by Hollywood’s chronic tunnel vision where matters of race and sexuality are concerned. Later films with Beat-related stories, including John Byrum’s tedious Heart Beat (1980), David Cronenberg’s lumbering Naked Lunch (1991), and Walter Salles’s long-gestating On the Road (2012), vary in quality but show more seriousness toward their subject.

Antagonism and suspicion on the part of ordinary Americans played a considerable part in publicizing the Beat subculture. A key Beat strategy was to give square culture a subversive spin—replacing the business suit with the work-clothes outfit, the clichés of Madison Avenue with jazz-inflected jive, the Protestant work ethic with a yearning for Zen harmony and peacefulness. This frequently stirred up a sort of moral panic among those who feared that the American way of life—meaning the white, married, middle-class, suburban way of life—might somehow be threatened, and who had trouble understanding why these youthful rebels were being allowed to have so much unconventional fun.

9. Popular culture capitalized on the Beat Generation’s fame—and notoriety—in many ways, as when Jack Kerouac’s novella The Subterraneans, published by Grove Press in 1958, was reissued by Panther with a lurid cover. Like the 1960 movie based on the novella, the book cover turns the black character Mardou Fox into a white woman.

The mass media reacted to Beat culture with both hostility and bemusement, simultaneously mocking the Beats and making them famous. A shining example was “The Only Rebellion Around,” an illustrated article by Paul O’Neil that appeared in a 1959 issue of Life, one of America’s most popular magazines. O’Neil likened the Beats to fruit flies infesting a succulent casaba, the latter being the United States in the Eisenhower era. The article’s photographs run along similar lines. A picture labeled “Languishing in His Pad” shows Ginsberg stroking a Siamese cat on a rumpled bed, and points out that two additional people, Corso and Peter Orlovsky, also live in this modest flat. The verdict is clear: guilt by messiness! A shot called “Horsing Around” shows Ginsberg playfully pulling a “scary face” at Corso, which bears out Kerouac’s opinion that the media wanted to link the Beats with violence. And so on. Most pungent of all is a Bert Stern photograph depicting a Beat household complete with marijuana, a half-written poem in a typewriter, and a Beat baby sleeping on the floor.

It is not a pretty picture. But it is a picture that one would expect from a middle-class magazine of the 1950s that associated the Beat Generation with skid rows, flophouses, hobo jungles, and slums. Fictionalized and fraudulent though it was, this Life article was a significant influence on public attitudes toward Beat lifestyles.