Chapter 8 - THE SAD TOMB LIST

Egypt – Present day

The BEAS-CEA agreement called for a register of all the tombs in which we identified structural defects and our proposed solutions. The Boards of both organisations would then mutually establish priorities, approve repairs and assign non-structural issues to other specialists as our team made no pretence to being archaeologists, excavators or restorers. Our brief was limited to assignments as simple as repairing broken stairways or as complex as the solidification of Esna shale. It encompassed the repair or replacement of damaged pillars, reinforcing ceilings, strengthening walls that could fracture or fail, in fact, the whole gamut of problems inherent in rock cut tombs. All very simple, deceptively so, as we would discover. Early in the negotiations, despite pressure from a handful of Society directors and the Egyptian Minister of Tourism, it was further agreed an investigation of tombs in the Valley of the Queens would be deferred as it was thought we should demonstrate our skills before taking on the whole of Egypt’s engineering problems.

Within two months of my arrival in Egypt, the rest of the team reached Luxor, settled into their accommodation, did a little sightseeing and found all the bars and nightclubs the city had to offer. I had personally selected Richard Lewis as our Site Manager, with the recruitment of the other three engineers being processed through the Human Resources Director in London. The minimum criterion called for university graduate mining or civil engineers with field experience in refurbishment projects at historic sites. Roger McKenzie, a Scot, had worked on the restoration of an Islamic mosque in Turkmenistan. Wilson Sinclair, a New Zealander, dirtied his hands in Aztec and Mayan ruins and Michael Davidson crushed a few fingers working at Angkor Wat, the ancient Khmer temple in Cambodia. None professed any problems with claustrophobia, all were single and, most importantly, they had worked with indigenous labour. As Roger commented ‘working in the Valley would be a piece of cake after the rigours of Turkmenistan labour disputes, which had occasionally been resolved with Kalashnikovs’.

Richard added zest to the team as he was a Scottish eccentric of the type found at Highland gatherings around the world. At the formal level, Lewis, MA in Mining Engineering from the University of Edinburgh, was a hard rock engineer. Before achieving his second degree, he had specialised in geological hydraulics in the ultra deep gold mines of South Africa, an area of expertise of critical importance when it came to sorting out the unstable geology in the Valley. He was a no-nonsense engineer, complete with horny hands, brawny forearms and hair rising stories about rock bursts three kilometres down in the Roodepoort Deep gold mine outside Johannesburg. His lack of ancient site work was compensated by his intimate knowledge of rock mechanics.

Recently divorced and looking for something more interesting than working down deep holes chasing gold veins, he was the ideal man to ride shotgun on this project. ‘Hard rock disnae go wi’ a gentle woman’ he declared during his interview in London. Living in the New South Africa could be fatal and, whilst as a single man he was not personally worried about being killed, he admitted that attending too many funerals of friends or their family members had worn him down emotionally. Richard claimed to be able to drink any man under the table which led to some high spirited parties during his assignment. He had the knack of getting the best results out of indigenous labour, an absence of fear in the claustrophobic confines of tombs and his love of working with rock.

“Laddie, you have to listen to the rocks as they will talk to you. You get to know when they want to move or when they are happy being still. If you push them too hard, they will push back. Working with rock is like working with a horse. If you gentle it, then you can bend it to your will and once the rock knows who is the master you will never have any problems.” he confided at a fairly alcoholic party in London. When I chided him, his response was quick.

“You Sassenachs dinna understand rock. You play with cement and steel, laddie, but when all these playthings you make ootta these wee materials have crumbled into dust there will always be rock. Look around you, laddie. The Egyptians wore kilts like we Scots and they knew what they were doing when they used stone 3,000 years ago. Do you think anything you have built will still be standing in another three millennia?” I had not thought it a good idea to mention Roman concrete as discretion is still the best part of valour when dealing with a semi-inebriated Scot.

The man strode around in either tartan trews and waistcoat or a kilt and was of resolute conviction, like most Scots, that the bagpipes was the only musical instrument sweet to the ears of Mankind. He professed great virtuosity with the pipes and played a vast repertoire of Scottish melodies. Colleagues made no adverse comment within earshot but uttered unkind words elsewhere, though the Egyptians loved him as he could endlessly entertain them. Of course, they knew beyond doubt bagpipes and kilts were Egyptian developments, a claim they swore was verified by images on walls somewhere in the country. He mastered Arabic with an accent comprehensible only by his workmen. He is one of those rare site engineers who can make himself understood without the need to raise his voice or issue threats. However, his temper was volcanic when he encountered total stupidity. We respected him for his unerring judgement in his field and he many times averted disaster after listening to his rocks and determining their compliance to our ministrations.

Together with Elizabeth, the team now had depth in theory and practice, wouldn’t complain about site conditions and could happily work with the varying quality of our labour force. At our first site meeting, I spelt out the ground rules.

“Okay, people, let’s make a start. You know the pack drill. If you think you are doing or saying the wrong thing, you probably are. This is a Muslim country, so observe the law and local customs scrupulously, be careful around women, Arab or Western, and do not get drunk in public or come to the site under the influence. No souvenirs except those you buy in the bazaar. Even then, be careful of what you buy as you don’t want to end up being charged with dealing in stolen antiquities. Take nothing from any tomb, no matter how insignificant you think it is.”

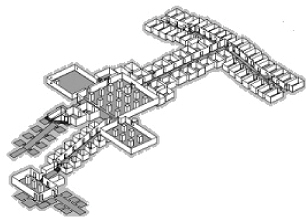

“You were all briefed in London about the scope of our work. Right, have a look at this map. It shows the location of all sixty-three tombs in the Valley and the other twenty or so pits that have been classified. First, note the four tombs under active conservation. We are not permitted any involvement with a site currently being explored or conserved unless asked by the organisation holding a permit. I will introduce you to the people working on these tombs as I think you will find they have lots of valuable information to exchange with us. Several of the team leaders, like Jean-Claude d’Argent and Otto Schaden, have been working here for years and you will profit immeasurably by listening to them. Advice we give freely but you cannot work in any tomb outside our brief unless I personally approve it. Remember, although this is a project related to an archaeology mission, the Society’s bean counters view our mission strictly from a business perspective and I am accountable for every dollar spent.”

“The brief excludes tombs open to the public and these are marked off in red though our initial task is to survey the lot. In the filing cabinets, there is a mass of data you will find useful. Before you arrived, Elizabeth and I assembled whatever information we could find on each tomb, including its history and current condition. Some observations! I have already met the top men in the Council and we have come up with an informal list of strong possibilities. Read that as tombs the CEA believe need our attention and will get the green light. I have highlighted them in blue on the map. Naturally, the CEA people have an open mind on modifying the informal list but I think you will find their assessment is spot on.”

“A major part of our brief is to devise a method of protecting dormant tombs with some mechanism that seals them from further attack, natural or human. Elizabeth will give you a copy of the guidelines the CEA drew up some time ago. Familiarise yourself with the requirements which will draw upon our mechanical skills. I believe to we can develop possible solutions a bit further down the line.”

“Our third objective is to prepare potential project reports on the tombs requiring structural intervention. Each report must be comprehensive as it may become the basis of an approved operation. They must include full descriptions of the issues, your recommendations and the probable cost and duration of each project. Richard and I will hold your hand if you are in doubt or have any problems beyond your ability or experience. Do not be afraid to ask either of us about anything. Richard thinks he knows everything, though he would be wrong, whereas I do know everything but then again I was born south of the Scottish border.” This brought hoots of derision from both Richard and Roger.

“Elizabeth provides logistics back-up together with considerable experience in field operations but keep in mind, she is not your secretary. You make your own coffee in the office and do your own typing and filing.”

Richard asked “How long do we have to assemble this register? There seems to be a mighty lot of holes in the ground?”

“I have allowed three months for the field survey and developing bright ideas about tomb protection. As many of these structures are simple affairs the bulk of your work will be on the major tombs. I recommend an early start, before it gets too hot, and an afternoon break before resuming work around two o’clock. You will quickly learn the hours as the Egyptians know how best to work with the climate. We will meet at seven o’clock every day to review progress. Friday is your day off although you will find Richard, Elizabeth and me in this office most Fridays. Please feel totally free to put in the extra unpaid hours. The coffee pot is always on. Questions, please?”

We worked through the day, building a rapport and it was encouraging to see a team meshing early in a project. Towards five o’clock, I announced. “Field work starts at the crack of dawn tomorrow morning. We will spend the first day or so familiarising ourselves with the topography and location of the tombs. Tonight, you will be my guests at dinner. We are going to spend a lot of time in each other’s company over the next few months and I hope we will continue to work as well in that time as we have today. I have read your resumes and you all appear to relish working on ancient monuments. Richard is the exception. His expertise appears limited to demolishing the contents of whiskey bottles but we can live with that.” This evoked a protest of innocence from the offender and good natured laughter from his colleagues.

“The opportunity to work here should give you all a buzz. Keep in mind, you will toil in structures built three thousand years ago and these tombs were the graves of Egypt’s most vibrant pharaohs. What we undertake will perpetuate the work of architects and builders who had the honour of serving these men and if you view our project in the same light, our endeavours will achieve great success and international acclaim. Elizabeth, gentlemen, thank you and good luck. We will meet in the foyer of the Grand Hotel in Luxor in two hours.”

Before we could lift a spade, the Society and Council had to agree to our recommendations. When I was given this gem of information, I protested that we could be tied up for months, if not years, in negotiations between both parties. Abdullah re-assured me, with the active support of his good friend, President Kamal, and the power of my father’s persuasive personality, decisions would be made without the usual bickering and ego massaging that dogged so many field missions. Against this background, the assessment commenced. We had our work cut out for us even after taking out the tombs that were being explored or conserved when we started. That still left seventy-eight sites in the East and West Valleys, an enumeration including small or unfinished tombs, those identified but still not fully explored and a few known but lost again since first discovered. We tried but did not succeed in re-locating the lost tombs – that would be a task for future archaeologists.

The actual definition of tomb is a little misleading as some of the sites had never been used for a burial though the majority fell into the classic definition of ‘an excavation in earth or rock for the reception of a dead body’. We struggled to find alternatives to tomb as the word became almost a mantra. We tried crypt, mausoleum, vault and grave site. A mausoleum is, strictly speaking, a stately or magnificent tomb, a description certainly applicable to the larger tombs. Richard fancied crypt, a dark word, usually used to refer to an underground burial place in a church and vault is best used to describe a burial chamber and both words are highly favoured amongst fans of vampire fiction. Bats are common within dormant tombs but we did not encounter Count Dracula, though we rarely worked at night as the Valley took on an eerie aspect after sunset and did not encourage nocturnal exploration.

KV5 could be considered a catacomb, a word normally associated with dusty warrens full of grisly desiccated bones, spider webs and stacks of heaped skulls, lit with flickering torches. Grave or grave site lacked the dignity normally associated with royal tombs. Looking through our written reports, it is amusing to see the grammatical somersaults taken to get away from the repetitive use of tomb. Liz took to scribbling little images of ghouls and goblins in the margins of her notes and despite, the gravity of our work, a degree of grave humour crept into the reports.

When we started collating data, Liz had proven to be invaluable in the compilation of the site register. It was an arduous task that involved scanning dozens of books and scholarly articles and using her feminine wiles when ferreting around in the Council’s reference library to extract information. Working with Elizabeth was a pleasure since it involved much innocent flirtation tempered by her very clear headed and logical mind. Cleverly, she managed to find any excuse to visit KV7, a project limited in its benefits to our efforts but then again, most of the Frenchman working in Ramesses I’s’ tomb were young, unattached and frequent patrons of the nightspots in Luxor. Possibly, she needed to improve her language skills given the vast literature available from the days of French domination of archaeology in Egypt. I dared not ask.

The condition of tombs open to the public had drawn some bitter comment from Yousef and Abdullah, although they were not going to engage in tribal warfare with the Minister of Tourism. Not all of these tombs were permanently available to tourists and several were in need of restoration. Ideally, we concurred that, these should be closed, comprehensively conserved and then re-opened but Egypt is not a perfect world and the Council was doing the best it could under very trying circumstances.

The tomb of Seti I demonstrates the dilemma. Howard Carter’s early repairs were adequate but cracks had re-appeared in the walls and the underpinning needed more substantial replacement. The tomb, one of the biggest in the Valley, has walls covered in lavish, finely detailed, painted decorations. So grand was the tomb, Giovanni Belzoni, its discoverer, mounted an exhibition in Piccadilly in 1821, featuring a model and a reproduction of two of the more intensively decorated scenes. To achieve authenticity, Belzoni took wax impressions of the decorations straight off the walls, removing much of the original paint in the process.

Despite members of the team having their favourite projects, we produced the first edition of the Sad Tomb list- those in need of urgent intervention. It required some hard -nosed decisions as every site was worthy of endeavour.

Tomb |

Designated Occupant |

Dynasty |

KV4 |

King Ramesses XI |

20th |

KV10 |

King Amenmesse |

19th |

KV13 |

Chancellor Bey |

19th |

KV14 |

King Setnakhte and Queen Tawroset |

20th |

KV15 |

King Seti II |

19th |

KV16 |

King Ramesses I |

20th |

KV20 |

Queen Hatshepsut |

18th |

KV36 |

Mahirpra |

18th |

KV38 |

King Tuthmosis I |

18th |

KV42 |

Queen Meryetre Hatshepsut |

18th |

KV46 |

Yuya and Tuya |

18th |

KV47 |

Siptah |

19th |

There was extensive work underway in four tombs at the time of our survey. Dr. Kent Weeks, investigating the massive KV5 complex, was clearing sections of the tomb, repairing flood damage whilst trying to discover the outer limits of the mausoleum which was by far the biggest tomb in the Valley.

KV5-Sons of Ramesses II

Jean-Claude d’Argent, the leader of a French team, was well advanced with the mammoth task of excavating, stabilising and restoring KV7, the tomb of Ramesses the Great. The tomb, open since the end of the Ramesside Dynasty, had been ravaged by floods, vandals and the instability of the shale layer into which the burial chamber was quarried. Jean-Claude had taken on a project deemed impossible by most archaeologists, a view I strongly disagreed with. The late Twentieth Century saw enormous developments in rock stabilising techniques and whilst a costly and slow business, the burial place of Egypt’s greatest ruler was worthy of the attention being lavished on it. The eight piers supporting the ceiling of the sarcophagus chamber had collapsed bringing down a considerable volume of rock, leaving it almost unrecognisable as a man made excavation. No doubt, a meeting with d’Argent would provide us with an opportunity to learn from his experiences as the project employed engineers well practised in overcoming structural damage. His success buoyed us up as it proved that the most daunting difficulties in restoration could be met and bested.

Over in KV22, the team from Japan’s Waseda University had been involved in well respected restoration works since 1989 and Otto Schaden had just begun the clearance of KV63, the tomb he had only recently discovered.

We had listed twelve possibilities, far more than we could manage. It was soon time to meet with Abdullah and Yousef for an exchange of views and a more intensive winnowing. At this point, we all had to be politically savvy. The strident demands from the Minister of Tourism to open more tombs and relieve some of the pressure on existing sites did not necessarily make good sense from an archaeological or engineering perspective. The possibility of discord within government ministries loomed large and we needed the muscle of the Council to achieve a consensus on the final selection. A clash between vested interests could badly stymie the project and that was the last thing anyone wanted.

There were subtle issues involved. Trade-offs between the need to preserve the integrity of a tomb from a purely engineering point of view, as opposed to damaging or destroying the original monument, would need to be carefully considered. Worse still, two of our recommendations would compromise the original tomb architecture. This dilemma is fundamental to work anywhere in the restoration of ancient monuments. There are unresolved debates about such questions as should the Athenian Parthenon be rebuilt or or merely repaired? Was it better to leave piles of fallen masonry on the ground or re-construct the building as originally built? If a monument was designed with sixteen pillars and five had failed, should they be replaced or left at the site as it was? In Egypt, the wholesale removal and re-erection of the temples at Abu Simbel,the splendid restoration of Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple and the rebuilding of monuments on the island at Elephantine demonstrated what can be achieved with radical salvage or reconstruction projects.

We took a pragmatic attitude to structural failure. Where it had occurred, we recommended replacement to avert further collapse which would be disastrous, not only because of the loss of irreplaceable artefacts, but a sudden collapse might result in death or injuries. There was also a lot of ugly structural steel and timber supporting more than a few chambers in tombs, which we could eliminate with less obtrusive alternatives.

One of the easiest assignments would be the replacement of the rough timber roof supports straddling the sarcophagus in the burial chamber of Ramesses I (KV16). In the space of just under two hundred years, the roof of the chamber had gone from structurally soundness to being in danger of failure with the probable destruction of a priceless artefact. When first explored by Belzoni in 1817, the ceiling was solid. By 1930, large cracks were apparent in the rock above the red granite sarcophagus, so the ceiling was supported by some very crude but still effective timber bracing. Richard put forward a proposal for slimline stainless steel supports that would remove the unsightly timber whilst ensuring the roof did not fail.

Possibly the most recalcitrant problem, from an engineering perspective, is stabilising Esna shale in tombs. Put another way - if a contemporary mining engineer had to cut into or through shale, there was no particular drama as dealing with friable rock is part of every engineer’s kit bag. This was very different from attempting to retro-fix corridors or chambers anciently cut into this type of substrate whilst still trying to leave a tomb looking like a tomb and not an underground parking station.

There was one interesting twist in our assessment, an idea that led us to adding, controversially, KV20. A growing percentage of tourists looked for the thrill of the adrenalin rush evident in the growth of extreme activities. We felt KV20, if restored, would go onto the global chart of radical challenges and this unique tomb could attract very high entrance fees from adventurers not afraid to travel down deep into the earth in what was a very claustrophobic atmosphere. Carter famously said of KV20, ‘It was one of the most irksome pieces of work I supervised.’ James Burton, in 1824, observed the air was so foul it extinguished his torches and Kent Weeks, after his recent survey of the Theban necropolis, made pithy comments about the bats infesting the tomb, the stink of their excretions and the unnerving experience of exploring the steep, narrow corridors.

The next meeting with Abdullah and Yousef whittled the list down to projects we thought would garner the approval of both bodies. It was a good handful – RamessesXI (KV4), Ramesses I (KV16), Hatshepsut (KV20), Tuthmosis I (KV38), Hatshepsut-Meryetre (KV42) and Siptah (KV47).

I queried whether we should we add the tomb of Merenptah, (KV8) the son who succeeded Ramesses II? Carter had cleared this tomb, another open since its priestly plunder, whilst working KV20. Merenptah’s mummy, which ended up in KV35, was very salty and popular belief has it he was the Biblical pharaoh who drowned in the Red Sea with his army whilst in pursuit of Moses and his people at the beginning of their exodus from Egypt. Archaeologists knew this to be a fairy tale but it brought the tourists to his tomb. Abdullah responded to my question. “No, Merenptah’s tomb needs more excavation in the store rooms off the burial chamber. Even though the pillars in the lower end of the tomb are structurally damaged, they are sound enough for the time being.”

We spent most of the day assessing the proposed project files. Both Abdullah and Yousef were fastidious in their questioning as they appreciated the political difficulties looming ahead in the boardroom. Finally, as the sun set, Abdullah summed up. “Dennis, if these proposals are accepted, they will allow you to undertake some radical work whilst pacifying my friend, the Minister of Tourism. If we are given the go-ahead, you can quickly fix the less difficult projects so the Minister can re-open these refurbished tombs to the public, with the promise of seeing the restoration of two spectacular tombs approximating their original grandeur. That should keep him happy and out of our hair for a few years. I am confident that the President will support our personal recommendations. Congratulations, this is a job well done.”

It had been a long and gruelling few months but the magnitude of the task ahead was at last defined. Flying back to Luxor from Cairo, a sense of excitement began to dawn on us. Once approval was granted, we could get down to what we all enjoyed – the delights of physical endeavour and the production of tangible results. To celebrate the completion of the research, Elizabeth, Richard and I took ourselves off to the best restaurant in Luxor. We were well into the after dinner liqueurs when Richard piped up.

“You are going to have to help me with a matter that’s been niggling me since we started this work. Whenever I had a free night, I read everything I could get my hands on about the history of Egypt and the Valley, seeing I am working with a couple of experts in ancient history. I find the whole subject bloody fascinating but I cannot understand why you archaeologists have done so little to fix up the mess that exists here.”

“Steady on, Richard” I said. “It’s not our fault the tombs are in decay. Unlike a mine which is driven by extracting a mineral out of the ground to sell and make a profit, ancient tombs are a ‘not for profit’ business.”

“That’s eyewash, Dennis. The bloody place is crawling with tourists and I notice they have to buy tickets to get into the tombs. Tour buses are up and down the road like Oxford Street on a shopping day and all the tour operators seem to be well dressed. Somebody is making money out of the Valley. Why aren’t the returns being re-invested in the asset that’s drawing day trippers here in the first place?”

Elizabeth, a little offended by his comments, answered before I could.

“Of course, some of the money comes back to the Valley. A number of government bodies are spasmodically working on tomb conservation and restoration. You should have read enough about the activities of the Supreme Council of Antiquities and the CEA to know they have put in a lot of time and money into remedial work but keep in mind Egypt is not a rich country. Her population is growing at a phenomenal rate and the government has to get its priorities right and fixing monuments is not the highest item on their agenda. You must travel more so you can appreciate that the Valley is a fraction of the total monumental history of the country and the dollars have to be spread very thinly to keep services up to as many sites as is possible.”

A little admonished but still irritated Richard countered, “Okay, if it is not the government’s fault, then whose fault is it? In 1817, the big Italian, Belzoni, comes along, armed with picks, shovels and battering rams, finds tombs all over the place and leaves. A dozen Frenchmen follow, finding more tombs. Loret discovers them like a child on an Easter egg hunt. Carter and a merry band of Englishmen dig up a few more then, poof, nothing since about 1932 when Carter went home. I haven’t made a total survey but it seems to me not more than a handful of archaeologists have been doing any work in this place since then. In fact, I could make a list on the back of a match box and without any disrespect to their efforts, they all seem to be brush and trowel men.”

Liz had her back up as she had done her fair share of field work. “I think a few of the brush and trowel men would take issue with that description, Richard, but essentially you are correct. An archaeologist is on a quest to find information and every piece of information helps piece together the story in just the same way a geologist probes the ground before you get into with dynamite and rock drills. Archaeologists have an extremely important role.” she responded defensively.

“Then why are they walking around with hard hats on looking up apprehensively at the ceilings to see if they are going to come crashing down on their scones? As far as I can see, only Jean-Claude d’Argent is actually making an issue out of fixing up the tomb in which his trowel and brush people are working.”

“Again, that’s not entirely correct.” I said, rushing gallantly to her aid. “Many archaeologists try to repair structural damage but they have a limitation. Money. The universities they come from are departments of history, not engineering and even if the universities sent out engineers, they need money and lots of it. You know what this little venture is going to cost , millions of pounds and the only reason the money is on the table is because my father beat the bushes and successfully shook the money tree but before you ask why this hasn’t happened before, I honestly can’t tell you.”

“Think of it this way. The adventurers have gone, the great patrons like Davis and Carnarvon are relics of the past and the Valley’s tombs have, in one sense, fallen victim to the disciplines of science. The philosophy of data gathering rather than finds has been the rationale since the Tutankhamen discovery in 1922. I doubt you will find an archaeologist who wouldn’t give his eye teeth to have the money to do what we are about to undertake. Any self-respecting Egyptologist ranks saving the tombs from further destruction as highly as gathering information but, in terms of clout, the archaeologist is low man on the totem pole at his university. Few have the training or inclination to go out into the world of commerce and pass the begging bowl.”

Elizabeth reinforced my argument. “The archaeological community is principally concerned with the need to preserve what they can within their limited budgets. I admit that one gets the impression a sense of futility pervades archaeologists, when reading papers and listening to lectures. As fast as they conserve artefacts and undertake what work they can do to preserve the integrity of a structure, the host government clamours for more monuments to be opened to meet the demand created by an increasing number of tourists. You know enough about political and economic pressure just on this project alone to understand that, surely?”

Richard replied with some asperity “In my opinion there are too many tombs not fully evaluated, tombs discovered then forgotten and, whilst some may be of apparently negligible interest to the touring public and do not share the magic of the great royal tombs, they are all part of the fabric of the necropolis. We’ve looked at tombs that are totally neglected and even though one or two may have benefited by recent research, they are now abandoned again, left open to the elements and nobody gives a tinker’s curse. It’s bloody appalling. A blind man can see what will happen if there is another downpour. Water will cascade into half the tombs, bugger up more of the rock structure, wreck wall paintings and re-fill areas the trowel boys have patiently dug out. If I left my mine workings in a similar condition, my boss would be after me with a shot gun.”

“Richard, you are absolutely spot on with your last observation. I would have lost my job if I left the company assets unprotected and that is exactly what the royal tombs are, assets belong to the company of Egypt. You may get your chance if I can get you away from your rocks long enough to poke your hairy arms into the other side of the project.”

“What’s that, you wee Englishman?” he said with a smile.

“We are putting before the Council proposals to protect the lesser tombs with water tight doors and flood control barriers, so later generations of archaeologists and scientists can re-open, restore, conserve and then give them up to future generations to enjoy. I promise you, my father and I will pound the table hard to get this objective accepted. We may not be able to fix up every tomb in the Valley but we will do our utmost to protect them for the future. On that you have my word, you Highland barbarian.”

Our team believed we could easily deliver a battery of modern techniques to preserve these monuments for at least another millennia. To do anything less would be a dereliction of our responsibilities to the ancient architects and builders.

“Now have a last drop of whatever you are drinking as we still have a lot of work to do before I fly up to Cairo again.”

With this resolve in mind, the three of us bent to the task of ensuring we were well prepared for our meetings in London and Cairo. Obviously, we would need all the political muscle we could draw upon from Professor Dief and Sir Reginald if our conclusions were to prevail.