Chapter 16 – THE TOMB OF QUEEN HATSHEPSUT

Egypt - Present Day

Until the project was given the green light, I had not ventured into KV20. The tomb was on Roger and Michael’s list, so they had marshalled their courage and inspected it. Their reactions did little to induce me to duplicate their visit. My work was therefore confined to paper assessments and computer generated three dimensional images. Using photographs, measurements and the observations of others to guide me, I mapped out a theoretical approach. All very sanitary, completely stress free and proof that rank has its privileges.

During the overall survey, we all made determined efforts to visit as many tombs as possible to absorb the architectural rationale, study structural nuances and develop a feel for the environment. I discerned, in my colleagues, a growing respect for the ancient builders and a sense of amazement, as it gradually dawned on them they were actually going to work in the burial places of kings and queens. To give our work a human perspective, I took the team to the Cairo Museum where Professor Dief led us on an inspection of New Kingdom artefacts. When we reached the royal mummies exhibition, I made sure every team member closely studied the remains. When the tour ended, I drew them together.

“Every time you enter a tomb, I want you to remember what you have seen today. You have the privilege, rare amongst engineers, of restoring the resting places of kings, some of whom you have now seen. These men walked where you have walked, they felt, under their hands, the same stone you will work and ultimately lay in the burial chambers we will restore. Treat every aspect of your work with reverence and your success will bring you a sense of achievement and pride unique amongst members of our profession.” Later, Abdullah told me I grew more like my father every day, a remark I still cherish.

When the KV20 project was endorsed, Liz prepared a comprehensive memorandum to add flesh to the bare bones of the restoration. I thought it important my team became familiar with the each of our project’s original patrons especially as the mists of obscurity shroud Hatshepsut and her reign. Her father, Tuthmosis I, sired no son from his first marriage but he did produce a daughter, Hatshepsut. Subsequently a son, later Tuthmosis II, was born to a second wife and the princeling entered into a marriage with Hatshepsut, his half sister. Though Thutmosis II only enjoyed a short reign, he apparently fathered a daughter with Hatshepsut. A male child, who later became Tuthmosis III, was born by a second wife, demonstrating that personal relationships in royal families could get very complicated. On Thutmosis II’s death, Hatshepsut became regent to the rightful king, who was then only a young boy.

Early in her regency, Hatshepsut took the unconventional step of declaring herself co-ruler and moved quickly to adopt regnal titles. Meeting no censure, or ignoring it, she boldly proclaimed herself king of Upper and Lower Egypt. She ruled for twenty years as the pharaoh when, quite suddenly, she disappears from history. Did she die of natural causes? Did Tuthmosis III oust her in a bloodless coup, asserting his right to the throne? Tuthmosis appears to have taken his revenge as, at some time after her death, he decreed her name be obliterated and her images smashed. Hatshepsut had denied him the throne for two decades and he was possibly strongly motivated to remove any reminder of the woman who forced him to endure lonely, powerless years exiled in Memphis. Just how Hatshepsut managed to deprive her step-brother of his birthright, without creating a furore, is part of her mystique.

Hatshepsut’s contribution to Egypt’s monumental landscape is noteworthy. Her expansion of the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak helped promote the cult centre of the god into a national shrine. She erected two forty-seven metre obelisks in honour of her husband, commissioned the Palace of Ma’at between Karnak and Luxor and built a little architectural treasure, the Red Chapel, to house the barque of Amun. By far her most impressive legacy is her graceful mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, which is set dramatically against the backdrop of the towering escarpment of the Theban Hills. Later, Tuthmosis hatred became palpable. He ordered built walls around the two obelisks in an attempt to hide them and defaced or plastered over her name throughout most of her temple.

The queen took blatant, though essential, steps to create the appearance of the divine sanctification to her claim to the crown. Though Hatshepsut was a descendant of royal blood, being a female and adopting pharaonic rank demanded more to legitimise her hold of the throne than merely bearing the symbols of power and dressing like a man. The queen’s buildings were liberally endowed with inscriptions showing her dedication to the deities and the images she raised in honour of herself as the son of Amun are carefully descriptive of her close association to the god.

When she was just a royal wife, a less than spectacular crypt was quarried for her high above ground level in the south-western edge of the Theban necropolis. She abandoned this tomb during her reign and it is thought she built KV20 as her resting place but whether she was the originator of the tomb’s construction is a matter of conjecture. The most popular theory claims that her father commissioned the tomb for his own burial but died before it could be completed and then Hatshepsut took it over and extended it. Looking at the plan, it is easy to visualise the first chamber as the beginning of a series of rooms, including a burial chamber. By adopting her father’s work, Hatshepsut may have sought to add another endorsement of legitimacy to her rule, especially if her father had already been entombed in the upper chamber.

Her tomb, like her life, is enigmatic. It is situated high up at the end of the most easterly arm of the Valley at the foot of an artificially widened fissure in the escarpment wall. Richard reasoned that there must have been some, long destroyed, method of sealing the tomb against the entry of water as its entrance is like a drainage hole at the end of a funnel. It is hard to believe her builder was not aware of the threat flood water presented, although there is little indication the entrance was quarried in a manner to combat this hazard. We were discussing this aspect one afternoon when Elizabeth offered an observation.

“We know the tomb of Ramesses II was subject to at least ten major floods. The evidence gained by digging through the strata is clear but consider the infrequency. Ten floods in three thousand years made this a very rare event. The Valley was used as a royal cemetery for just over four hundred years, yet it is possible there was no cloudburst during its active life. The climate then may have been hotter and drier than it was later in Egypt’s history. Maybe, the ancient builders looked at the Valley, saw the effects of water damage – erosion and culverts - and thought that was either how the gods formed the valley or, more likely, considered the damage was purely historic and non-recurring.”

“You could be right.” Richard ventured. “Egypt appears to have been a land of constancy. I should imagine nothing much changed in climatic terms right throughout the three millennia of the ancient civilisation. The Nile flooded like clockwork, the desert didn’t advance, there weren’t any volcanoes to erupt and no record shows any natural cataclysm blighting the country other than the occasional failure of the inundation and the resulting famines. So maybe the Egyptians thought theirs was an unchanging land created in toto by Atum, their creator god. The political and religious upheavals may have modified the face of the government momentarily, though the whole system of government, art and even the basic elements of architecture remain largely unchanged. What you see is what you get.”

“That’s not totally correct. Architectural styles did vary,” I said. “Nevertheless, I should imagine rain was a very rare occurrence. Water, for the Egyptians, came from the river and not from the sky. There is another consideration. The Valley flooded in 1920 and 1994 and anyone who has anything to do with the place, is concerned about a repetition of the damage caused. It would be interesting to find out when the last floods occurred before the Twentieth Century. I wonder if there are any meteorological records that might show us a rainfall pattern in the Valley? For that matter, I should ask Abdullah if there is anything in ancient records mentioning floods and heavy rainfall. Did the Egyptians even have a word for ‘rain’?”

Liz replied “Dennis, you must study hieroglyphs more intently. Of course, the Egyptians had a sign for rain. Don’t you think it rained around the Delta?”

“I stand admonished. Forgive me, learning Arabic is time consuming enough. Another possibility. Imagine this. You are in Thebes and the heavens open. Would your first thought be to rush over the Nile and have a look at the Valley to check for rain damage? Even if someone, say workers from Deir al Medina, saw water pooled on the valley floor, what would they do about it? In the heat, water would have evaporated within a few days and I think it unlikely the temple had a damage control crew sitting around in Wellington boots and raincoats.” Richard offered “That’s a more logical solution. Even if water flooded into tombs, no-one was allowed to open them so any damage sustained would be hidden.”

Design work immediately started on a canopy for Hatshepsut’s tomb because an extensive rainfall, when it came again, would cause water to cascade into the tomb and ruin the restoration. Designing this particular device gave me reason to talk with Tamaam more frequently, an unexpected oasis in a world of drawings, cost schedules and material requisitions.

When Hatshepsut proclaimed herself pharaoh, there may have been only four other tombs in the valley necropolis, Ahmose, her father Tuthmosis I (KV38?), possibly one for her half-brother and husband, Tuthmosis II and that of Amenhotep I (KV39?). No tomb has been clearly identified as belonging to Tuthmosis II, hence the theory he planned KV20 as his burial site.

The layout of KV20 was essentially simplistic. The first unfinished chamber is about sixty metres from the entrance. The rest of the tomb is one long corridor, of some 150 metres, leading to two large chambers with three side rooms. It lacks the sophistication of later tombs, as subterranean tomb design was in its infancy when it was quarried.

What makes the tomb so different from all the others is its alignment, the steep angle of descent and its length. Its axis changes from east, then to the south and back towards the east in a clockwise direction with the burial chamber turning back towards the entrance but 97 metres lower. The tomb was known to the Napoleonic Expedition and later mapped by Belzoni, Burton, and Lepsius. It was only expertly excavated by Carter in 1903-04. Romer concluded the tomb was made for a predecessor of the queen, who usurped it and extended it for her use and the re-burial of her father.

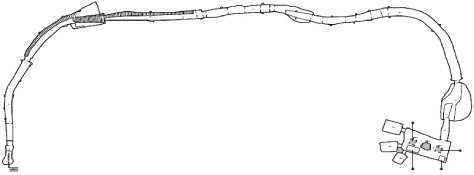

KV20

Whatever the factual history, the tomb was undoubtedly ransacked in antiquity but by whom and when is unknown. There was an interval of about 360 years between Hatshepsut’s death and the mass pillage at the end of the Ramesside Dynasty. The mummies of Ahmose, Amenhotep I and Tuthmosis II, all of whom predeceased Hatshepsut, were found in the cache in DB320. The queen’s mummy and coffin remain undiscovered, although a chest bearing her cartouche was found in DB320, containing what may be one of her organs. Did the robbers assault her tomb or had her body been previously disinterred by Tuthmosis III in a fit of pique and re-buried in an unmarked grave? The entrance was so prominent it is unlikely the grave robbers would have overlooked it.

There had been no conservation work since Carter’s investigation. The tomb, which starts in limestone before hitting shale just after the first chamber, was completely devoid of decorations, save for fifteen limestone slabs inscribed with stick figure drawings from the Books of the Dead, which Carter found in the burial chamber and sent to the Cairo Museum. They may have been embedded in the walls as it wasn’t possible to decorate shale walls. Carter also removed the two red painted quartzite sarcophagi he found in the crypt. In 1994, it was flooded and the lower levels again filled with debris. On the bright side, it was a civil engineer’s dream. We didn’t have to worry about damaging decorations, the burial chamber was cleared and there would be no artefacts in the debris washed in during the last flood. However, the tomb was not without it particular problems. Staircases had eroded, ceilings and pillars collapsed and our old enemy, Esna shale, lurked down in the darkness.

Of course, there were a few trivial problems. Richard’s report confirmed it was home to thousands of bats, the air was acrid with their excretions and, due to the appalling condition of the tomb and its steep incline, it was an intolerable place. Just after the first chamber, the corridor nose-dived. We could expect a slope of around 40 degrees, ventilation was non-existent and debris had to be dug out and long hauled to the entrance. New construction material would have to delivered great distances into the lower chambers down the steep corridor. Reading reports from people who had ventured into the tomb warned us that this would not be a fun place in which to work but we could envisage the time when extreme activity adventurers would clamour to ‘go down the mine.’

On a more serious note, our work would preserve one of the most amazing tombs in the country and an outstanding example of the skill of ancient builders who excavated it, using little more than copper chisels, wooden mauls and wicker baskets. Unavoidably, we needed a field trip, despite the reluctance written deep on the faces of my colleagues and I was not that keen myself. The corridors were, on average, only two metres square, much narrower than in most tombs, there was not natural light, crumbling stairs, the prospect of bats, stifling air and the possibility of rocks falling on our heads, none of which offered a powerful incentive to make the inspection.

Richard, who had spent most of his adult life underground, was the least worried. Elizabeth worked in offices or open field sites and she admitted to suffering a tinge of claustrophobia, even in the better lit and larger tombs. I was less concerned by virtue of my previous occupation, which compelled me to spend many hours inside confining metal ducting, walking through dam walls and other constricted places but the prospect of going 210 metres underground into a pest hole didn’t warm my heart. However, the inspection couldn’t be avoided, so I gritted my teeth and asked Richard to assemble sets of caving gear. I rang Yousef to see if he would accompany us - an invitation he immediately declined - or find us an Egyptian who knew the tomb. He promised to locate someone to guide us, remarking, with a touch of smugness, he would ask Allah to protect us in our descent into the Underworld. This from the man who recently complained to me about being endlessly stuck in his office.

The day of our inspection dawned brightly. Yousef had found a local who knew the tomb and his description of the joys awaiting us was enough for Elizabeth to promptly excuse herself from the mission. Richard arrived with breathing apparatus, hard hats, torches and a mass of climbing equipment. As we suited up, I asked what we should do if we found bats in the corridors. His advice was cryptic “Keep your head down and mouth closed.” Khalid, our jovial and loquacious guide, laughed and cackled like a child at a fun fair. He scorned our heavy climbing boots though he donned a respirator and hard hat.

“Are we ready?” he asked. He offered a prayer to Allah and I thought about beseeching a variety of gods to still my pounding heart. A much relieved Elizabeth waved us a cheery goodbye as we advanced, heavily encumbered, into the entrance. The short, smooth floored access way was narrow. It led to a longer, wider corridor with the decayed remnants of a flight of stairs down its left side. At the end of the first irregularly cut chamber, the long corridor descended steeply in a gentle curve. At this point, we first encountered shale. Beam holes had been cut into the walls for the placement of timber braces used to lower the sarcophagi by ropes, an operation that must have been very genial work for the labourers as they sweated and strained to manoeuvre several tonnes of a heavy, unwieldy quartzite box down a steep incline in semi-darkness. The corridor cut through a second small chamber and continued downwards, vestiges of the original staircase barely evident, before bending eastward with the angle of descent dipping sharply. By torchlight, I noted the ceiling had collapsed for most of its length.

There was a sudden noise above the rasp of my breath in the respirator. “Bats. Get down” yelled Khalid. I froze and Richard pulled me to the ground. I hate bats and suddenly there were thousands of them flying overhead, screeching in the dark as they took fright at our intrusion. Khalid threw stones down the corridor in an effort to dislodge the vermin from of their roosts in the lower levels of the tomb. I almost panicked but Richard put his arm over my back and steadied me. This was not my idea of jollity and I was badly frightened. Our helmet lamps didn’t offer much light and, as I looked downwards, I could not see more than about five metres ahead of me. We were way below the penetration of sunlight and lost in Stygian darkness. I took my face mask off for a moment to catch my breath and instantly regretted it as my nostrils were assailed by the stench of ammonia rising up from the bats’ excrement.

With the departure of the last of the filthy creatures, we resumed our descent into Hell. Climbing ropes were in constant use as we abseiled down the slope, each footfall placed with care on the unstable, befouled and stinking floor. When we finally reached the entrance to the antechamber, I was soaked in sweat, no longer sure of my orientation and again on the edge of panic. We could talk to each other by means of the microphones in our head sets and Richard kept re-assuring us all with calming remarks. Khalid didn’t seem to be fazed as he knew what to expect or he was a sewage worker in real life. I began to wonder whether our decision to repair this tomb was a wise one but this thought didn’t deter the engineer in me considering how to tackle the job.

At this point, flood debris blocked our progress. I bent down to examine the material under my feet. Beneath a layer of encrusted guano, it was hard packed and blows from my pickaxe told me digging out this mass would to be difficult and noisome work. All the horizons were shale and broken pieces mounded up everywhere. The walls and ceiling were badly fretted and cried out for stabilisation. We couldn’t see much of the burial chamber nor the side rooms but the environment duplicated Siptah’s chambers. At last. I heard Richard telling us it was time to return to the surface. “Thank God” I replied “I am scared out of my wits” not caring who learnt of my discomfort.

The ascent to the surface gave us another taste of the difficulty inherent in this amusement palace. As most of the stairs had crumbled away, the climb back was very hard going. Fortunately, the absence of decorations on the shale walls would allow us a free hand to widen and add height to the corridors. I was never so glad to get out of a place. I rushed out of the entrance, flinging off the respirator and took in gulps of the fresh air as did Khalid and Richard. We were sweaty, very dirty and probably smelt like a fowl house.

“Had fun, boys” said Elizabeth innocently. She held a camera to her face and was busy taking candid snapshots of the intrepid band of brothers. Richard was looking a touch pale and even Khalid was quiet. “Phew, you stink’ she said when I got close enough to make a grab for her camera. “Don’t you dare come near me. You are covered in bat guano” she said backing off quickly. “I saw them flying out of the tomb and disappearing into a cave up on the escarpment. Come, Brave Hearts, I think you all need to have a shower and a stiff drink.”

When we got to the jeep, I started to climb into the driver’s seat but was promptly told by Elizabeth to sit in the back with Richard and Khalid. ‘Very nice’ I thought, a lot of respect was being shown to the Project Director, even if he stank like a skunk. With immense relief, we drove away from the pest hole back to our headquarters, to shower, dress and reunite on the veranda. Khalid refused the offer of a drink and excused himself but Richard and I put down the first glass of beer with alacrity. Once we had calmed down a bit I said “What on earth possessed Hatshepsut to build a tomb like that? That was the most fiendish place I have been in my entire life.”

“Well, Dennis, I’m sure the Queen wasn’t going to make a royal visit down into the tomb whilst she was alive. Her motivation was probably only to dig something deep with an inaccessible burial chamber. I wonder if her builder hoped the long unstable corridors would ultimately collapse and permanently entomb her under the rubble? She knew she was unpopular with Thutmosis and thought he might try to dis-inter her body. If her tomb corridors collapsed, she would have denied him the pleasure.”

I replied “No, I doubt if she hoped or planned to have the tomb walls cave in. If that’s what she wanted, she could have ordered those who entombed her to back-fill the steep corridors once she was interred. Given the lack of stairs at the end of the third corridor, the steepness of the incline and the rough nature of the crypt, I think she decided “bury me deep and in a place none could penetrate”. I don’t see flocks of priest making that descent to offer up devotionals to her, do you?”

Elizabeth offered her opinion “I doubt if tomb robbery or post-death veneration was on her mind as her mortuary temple would be the most appropriate place to honour her memory. I am fairly sure the early New Kingdom tombs were viewed with much less importance than those built from the Nineteenth Dynasty onwards. Remember, nobody has found the tombs of Ahmose or Amenophis I. If and when their grave sites are uncovered, they might reveal that a royal burial wasn’t the florid issue the latter rulers made of it. I have another thought. She built her mortuary temple next to Mentuhotep’s. His burial chamber is 150 metres under and behind the temple. Is there the slightest possibility she wanted a tunnel connecting her tomb with her mortuary temple, which is just over the escarpment and directly behind her tomb?”

“How do you mean?” I queried.

“I may be talking rubbish but what if her long corridor had been built straight back towards the temple? The total length is 210 metres. Would that be long enough to reach her temple? I know the passageways are curved - maybe the builder lost his sense of direction. You became disoriented, Dennis. Richard, do you think it possible the builder lost his bearings?”

“Okay. First, did she know about Mentuhotep’s long burial chamber? Let’s assume she did. The builder obviously knew he had to tunnel down at a steep angle otherwise the excavation would collapse on top of him as there is no longitudinal strength in shale. I have no idea if builders of that time could work out relative depth levels. He would have to know the elevation of Hatshepsut’s temple and then calculate how deep he would have to quarry to end up under it. In answer to the question, yes, without fairly sophisticated equipment, it is possible to lose your sense of direction underground and just keep digging. I will have to get some topographical maps of the Valley and Deir al Bahari to test your idea but it is plausible.”

“Liz, you have the makings of a forensic archaeologist. If your theory is provable you will really set the cat amongst the pigeons. Unhappily, I doubt if we will find any answers in her tomb. Right, let’s get down to practical matters. We have to widen the corridors and extend lighting, stairways, handrails and ventilation as we descend. By consolidating the shale, all of the cabling and ventilation piping can be anchored into the hardened surfaces.” Richard said “It’s going to be a bastard of a place to work in. We are going to have to pick our workmen very carefully.”

We had earlier agreed that the only way to stabilise Hatshepsut’s tomb was to pressure inject isocyanate adhesive into every horizon. There was no plan to rebuild any of the lower rooms or install limestone plates anywhere as we hoped to leave the tomb looking as natural as possible except for the three damaged pillars which would be recast in concrete with shale bonded to their surfaces.

“I have recommended the Council order copies of both sarcophagi and the burial plaques and place them in the solidified burial chamber. It going to be an arduous trip no matter what is done to facilitate the descent and ascent and I think tourists should be rewarded with a faithful reproduction of the burial chamber as it was when Hatshepsut was put to rest. The existing stairs or what is left of them were cut into shale and to replicate them would be a waste of money. Let’s replace the lot with steel mounted timber treads. Enough for today. Right now I want some dinner and a good night’s sleep. Hopefully the next time we go down the tomb, I might be a little better prepared mentally. Question, how do we get bats out of the tomb permanently?”

No-one from the Council had been inside KV20 and we thought it essential someone in the pyramid of technocrats and bureaucrats should be in a position to deliver progress reports to the Governors in Arabic. Unlike KV47, where either Abdullah or Yousef could regularly inspect, it was unlikely either man would jump at the prospect of visiting Hatshepsut’s tomb in the early stages of the project.

Whilst we were not re-building the tomb, our actions constituted a radical departure from traditional conservation as it was the opposite of the precedent set, ironically, at Hatshepsut’s principal monument, her mortuary temple. The temple was in ruins before being comprehensively restored by a Polish team. Their intervention overwhelmingly demonstrates the value of reconstruction, as the result is spectacular and the temple is now viewed as one of the finest examples of pharaonic architecture in Egypt.

The queen introduced several style innovations, though she was heavily influenced by the layout of terraces, ramps and pillars at the mortuary temple Mentuhotep II built in the Eleventh Dynasty. Hatshepsut located her monument besides his temple, which was itself influenced by the configuration of the earlier rock cut tombs at Thebes with their square pillared facades. The principal difference between the two temples is the gracefulness and spatial orientation of Hatshepsut’s edifice.

I explained our problem to Yousef, prevailing upon him to seek out an adventurous staff member willing to be the project liaison officer. He rang back a few days later to tell me he had found one Council engineer and as many students as I liked from the Faculty of Architecture who volunteered to act as a reporting committee. This was great news and I hoped Tamaam and her brother were amongst them. I was quite captivated by the young gamine and looked forward to meeting her again with more than just professional interest.

Two weeks, later the Cairenes arrived at Luxor Airport, young, enthusiastic and innocently eager to make the descent into the mysterious tomb. Richard had gone to the airport to meet the visitors and escort them to our headquarters. They arrived with all the noise and excitement native to most Egyptians. He had regaled them with the story of our first expedition and they were laughing and talking volubly, probably at my expense. I looked for Tamaam as they disembarked from the bus and was momentarily disappointed when she did not appear. ‘Silly man,’ I thought. ‘She wouldn’t be interested in me.’

She was the last one off the bus. My heart lurched when she stepped down and looked straight at me, her lips smiling in recognition. She was more beautiful than I remembered, petite, with an exquisite body, glossy copper hued hair, finely chiselled features and those eyes. Her tawny coloured skin shone in the morning sunlight. We both froze. The students stopped talking and watched us. I felt myself blushing under my tan. Her brother called out “Mr. Dunlop, you have lost your voice? You no longer greet your friends? Your English blood is still cold despite our Egyptian sun? My sister wants to say hello.” Mahmoud bounded to my side, grabbed my arm and walked me over to Tamaam. How small and delicate she was.

The students and Richard all broke into laughter and there was much back slapping.

Random thoughts raced through my mind. ‘What is this, a conspiracy? Do these people know something I don’t?’ Egyptians from ancient times through to the present day are an incurably romantic people. Scattered amongst many of the nobles tombs are love poems dedicated to their wives. Several pharaohs were effusive in their love of their queens, there are many images of husbands and wives, in very affectionate poses, decorating the walls of family tombs and museums are replete with statues of married couples in loving embrace.

“May I call you Dennis?” asked Mahmoud as his sister stood shyly beside me.

“Of course.”

“Dennis, my sister has done nothing else but talk about you since our first meeting in Cairo. It is ‘Dennis this’ and ‘Dennis that’ and she has been as excited as a child since the possibility of this trip was first raised.” He momentarily drew me aside and whispered. “Please look after her and treat her with respect. Never do anything dishonourable as my brothers and her father guard her virtue closely. She may be a young woman but my sister has always known what she wants from life. Continue to be the man I think you are and everyone, especially Tamaam, will be happy.” He turned, looking for Richard. “When does this miserable journey to the centre of the earth begin?”

I thought it politic not to stay too close to Tamaam at this time, despite blatant efforts by the students to make sure they were not in our way. Richard kitted the group out with their equipment. He warned them about the dangers and took great pains to explain the use of respirators and climbing equipment. Finally, he asked them again if they were all sure they wanted to go down into the tomb and, once he had their assent, we made for the entrance.

Enquiries had been made amongst the madmen who actually enjoyed working with bats about how to get them out of the tomb. We took the most humane method of lowering a loudspeaker to the bottom and played very loud, discordant music for a few days and nights. The bats, deeply offended, fled and had not returned since. At least, I would not face that nightmare again.

We all carried high intensity torches to assist us in surveying conditions as we proceeded. I briefed the group about the overall layout and the environment they would find and asked them to keep notes of what they saw. We had copies of the diagrams developed by the Theban Map Project team and, as our respirators had a two hour supply of air, we had ample time to make personal observations. Richard warned them the slope started almost as soon as we passed the first gate but there were gasps of surprise at the steepness of the downwards incline. The initial sharp descent would be a great marketing tool with which to capture the imagination of adventuresome tourists.

I felt much more secure this time. More people, no bats and greater illumination all served to calm my fears. Looking more closely at the tomb’s overall condition confirmed it was a wreck and had badly deteriorated since first quarried. By no definition, was it a beautiful structure and it would never compete in elegance with the more decorative tombs. I was intrigued by a comparison of this, a royal tomb, to the two tombs of Hatshepsut’s vizier, Senenmut. The first to be discovered was the largest rock-cut tomb in the Western Thebes necropolis. Although now badly damaged, it had been elaborately decorated. His second tomb is not quite as ornamental but it has the first known astronomical roof painting in Egypt.

When compared to his master, the Queen, Senenmut went to the Afterlife in near regal splendour, whereas she had been consigned to a long deep hole in the ground devoid of artistic features. A very interesting situation, indeed. I wondered if Hatshepsut was buried somewhere else in a much more elaborate tomb as the juxtaposition between her tomb and her vizier’s was irreconcilable.

If not for the presence of the two sarcophagi bearing royal epigrams I’d entertain serious doubts about KV20 being a royal tomb at all. The larger quartzite sarcophagus is inscribed with Hatshepsut’s cartouche and regnal titles. The second has those of her father, Tuthmosis. I liked the idea she thought those who followed her reign could never reconcile themselves to a feisty female Pharaoh and would seek to desecrate her grave. By building such a difficult tomb, possibly she hoped to deny them the pleasure but then, she under-estimated the venality of some of her fellow Egyptians.

We reached the end of the tomb and the debris which almost filled the burial chamber and most likely the three side chambers. One of the more adventurous students slithered across the rubble and disappeared. When he scrambled back, he indicated he had something to impart when we returned to the surface. The ascent slowed as we surveyed the environment. Some careful jockeying by Richard and Mahmoud had Tamaam teamed with me from the beginning of our odyssey and there were opportunities aplenty to take hold of her hands during the mission. The first wonderful shiver of electricity between us was delicious. Finally, we emerged into the sunlight and headed for the showers. The bats may have fled but their stench remained and the visit had left us all sweat streaked, smelly and caked with dust.

“Hardly a romantic first date, Dennis, my boy.” said the ever helpful Richard as we dressed for lunch.

“Richard, this is ridiculous. She is years younger than me, comes from a Muslim family and is absolutely divine.”

“So what’s the problem, Dennis? She’s no bimbo smitten with a slightly older man. Tamaam is a mature, well educated young woman from a different culture. Enjoy the experience. No doubt you have done a lot worse in your miserable life.”

We gathered for lunch and spent the rest of the afternoon comparing notes, throwing ideas onto the table and looking for solutions to technical issues. The young man who clambered into the burial chamber said the debris only partially filled the crypt. However, he confirmed only the stumps of pillars remained, adding that, although he had sighted the three smaller chambers, he could not access them. Towards the end of the afternoon, Mahmoud announced he had called a friend in Karnak who owned a restaurant and asked whether would we like to join him and his friends for dinner? He looked at me and smiled. “Tamaam wants to know if you can dance?” She blushed furiously and I am sure I turned a little red myself. These Egyptians certainly were not backward in coming forward.

The evening was pure magic. The restaurant was at the southern end of the Temple of Amun. Spotlights lit up the pylons, halls and statuary at the great monument, the moon was full, the night warm, the food delicious, the wine excellent, the conversation scintillating and beside me all evening, was this woman who combined seduction with innocence. Egyptian men and women rarely dance together in public so we were treated to the men performing traditional village dances and then the women took their turn on the floor. In a society constrained by the teachings of the Prophet, there is something subtly erotic about Arab women dancing. The way they move their bodies and hands is sensual in the extreme yet without a suggestion of lewdness. Most Arab women have highly expressive dark eyes which seem to flash in moonlight and they know how to use their eyes to the greatest effect. When Tamaam danced, she turned her eyes to me and those eyes were full of promise.

Once the older dinner guests had retired for the night the younger men and women could dance together. By then, every member of our party was aware of the tension between us and when the music turned to a slow European style, we were showered with requests to dance. I have never been a good dancer but on that night I danced like Fred Astaire. Tamaam floated in my arms and leant against my body, her head on my shoulder, her hair warm against my neck.

During a break in the music, I held her away from me and said “Are you my Egyptian Princess?”

“Yes, Dennis, and you shall be my English Prince.”

The Cairenes were on the early morning flight and I had little opportunity to see Tamaam before they departed. At the airport we took leave of each other with an awkward handshake, which occasioned much cheering from her colleagues. Returning to the office, I silently contemplated my memories of the night. Richard kept his counsel until we reached the compound. As we got out of the jeep, he said,

“Laddie, you have found yourself a prize and I envy you your luck. Look after this woman and she will reward you greatly.” I knew he had been married and divorced but he spoke little of his personal life. There was a woman somewhere but he never mentioned her and I respected his privacy. “We will be in Egypt for many years and having a good woman by your side during this time will be a great blessing.”

“You sound as though you think I am going to marry Tamaam.” I replied, somewhat taken aback by his seriousness.

“You would be a bloody fool if you didn’t. We have both had our share of women, both been married and divorced but have you ever been hit by a thunderbolt?”

“No, not until now.” I admitted. “I thought I loved my former wife but our falling in love was an act of lust. No music, no thunderbolt and, looking back, no real chemistry other than physical heat.”

“Somewhere in one of the books about Socrates, there is a story discussing the origins of humans. The Greek gods fashioned a creature, neither male nor female. These creatures became arrogant and finally they turned their backs to the gods, so Zeus took a lightning bolt and hurled it down to the ground. When it hit the earth, each organism broke into two pieces and the pieces were scattered around in chaos. Since then, each half has been looking for its partner in a desperate desire to make itself whole again. I like to believe this story as it explains the few really happy relationships I have seen in my life. I think, in Tamaam, you have found your other half. If the chemistry is right, then so the relationship will thrive. You are a fortunate man, Dennis, and I hope Zeus is watching the re-unification of one of the divinely created beings.”

“Richard, I didn’t take you for a romantic but I like the story and hope you are right. She has completely knocked me off my feet and right now I am in heaven which is a bad place for a civil engineer to be. Totally illogical and impractical. Come on, we have work to do.” I clapped him on the back as we arrived at my office door.