Chapter 23 – THE TOMB OF RAMESSES II

Egypt – Present Day

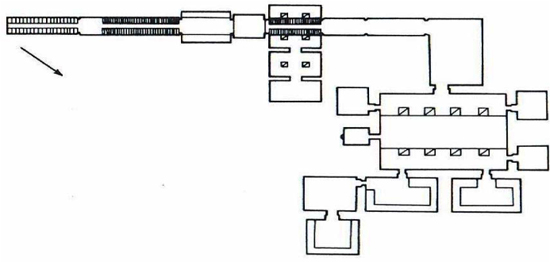

The tomb Ramesses II had prepared for himself was an anachronism, as it replicated the style of the earlier Eighteenth Dynasty tombs, all of which turned on their axis at some point along their length. The tombs of the rulers who preceded him, Ay, Horemheb, Ramesses I and his father, Seti, were typical of the layout of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasty tombs, all of which were quarried along a single axis. The other exception was the tomb Ramesses built for his children but it radically departed from any known design concept to become a subterranean city of the dead and closer to being a catacomb.

There was no overriding geological reason for turning the bulk of KV7 ninety degrees at the end of the straight corridors, except for some evidence of Esna shale low on the northern wall of the antechamber which may have caused the builder to return to the safety of limestone. He was unfortunate. The imperative to excavate downwards inevitably drove him back into shale.

KV7 was quarried into one of the first buttressing hills on the western side of the East Valley. A ramp would have led up from the valley floor to an entrance framed with a crescent of limestone chips and, possibly, protective walls and channels built to deflect flood water. Nineteenth Dynasty tombs were sealed with heavy, hinge mounted, ornamental cedar doors as the earlier practice of plastered masonry walls had been abandoned. When KV7 was pillaged, everything of value would have been quickly stripped out, the tomb left open and neglected. Honour in death, even for a king as magnificent as Ramesses II, proved to be transient.

The immediate years after the dynastic collapse marked the beginning of the Valley’s decline into centuries of near obscurity. The village of Deir el-Medina, home to the skilled craftsmen who worked on the tombs for over four hundred years, was abandoned as artisans and their families moved to where their talents were more eagerly sought. Temple priests and guards left and the valley remained unused as a cemetery although there were intermittent, intrusive, burials in the Twenty-First and Twenty-Second Dynasties when several tombs were usurped by the Theban nobles, some of whom recycled the empty sarcophagi and royal coffins for their own internment.

Over millennia, infrequent torrential downpours assailed the Theban Hills and water washed vast quantities of limestone detritus into Ramesses tomb, almost filling it with rock like accretions. For over five hundred years, after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, a handful of Greeks and Romans visited the upper reaches of the tomb and left their graffiti on the walls. It is recorded in the chronicles of the Greek, Diodorus Siculus and the Roman, Strabo, that at least twelve Valley tombs were open as their entrances were so prominent they were never submerged under stone chippings, unlike tombs with more restricted portals.

In 642 AD, the last representatives of the Byzantine Empire fled when Egypt fell to a Muslim Arab army advancing under the banner of the Caliph. The Valley is then only briefly mentioned in Islamic documents and the place maintained its long quiescence. In 1707, the first known European visitor, Father Claude Sicard, a Jesuit priest, noted ten open tombs, one of which was probably KV7.

It is commented upon by the English explorer Richard Pococke in 1743, James Bruce in 1768 and featured prominently in the manuscripts and maps complied by Napoleon’s scientific expedition. Thereafter, it was visited by almost every famous name in early Egyptian archaeology - Belzoni, Hay, Wilkinson, who gave the tomb its modern numerical designation and Salt, who attempted some excavation in 1817. Champollion and Lepsius undertook minor exploration in 1884. Lepsius crawled down to the burial chamber and later diagrammed an almost perfect plan of the tomb. Harry Burton (1913-1914), Howard Carter (1917-1921) and a team from the Brooklyn Museum in 1978 all undertook limited excavations.

Burton wrote in 1913.‘It was necessary to pull down a great dealt of the ceiling. (in the first corridor). (Two days later) First passage finished, commenced second passage. The ceiling was unsafe, pulled down a great deal. The sarcophagus chamber is in a very bad state. All eight columns have fallen and brought down much of the roof with them’. Burton gave up, deciding the tomb too unstable to continue any further excavation, observing the tomb had limited stylistic value because the wall decorations were so badly water damaged, little of merit remained. Carter encountered problems with the stability of the tomb ceilings, judging it was dangerous to work amidst the devastation. There is every indication Ramesses chose a very unsound location for his tomb which had, with hindsight, everything working against it - poor quality limestone, an unstable shale foundation and an appalling position in relation to flood water intrusions.

KV7 was written off as a tomb too hard, despite the stature of its provenance. Though not the worst tomb in the Valley, it certainly ranked amongst the top prize contenders. Then, in the fine tradition of the French with their long and intense association with Ancient Egypt, Jean-Claude d’Argent and his team from the French Academy of Antiquities, launched a rescue mission and restoration began in 1994. The project was hampered by earlier structural failure, the ever present hazards of recurrent rock falls and debris removal. Just as onerous was the desire to conserve what little remained of the decorations.

I knew little about conservation work and sought guidance from al-Badawi, a highly qualified restorer and conservator. Whenever he and Liz, herself an experienced field worker, got together to instruct me in their discipline I detected a deep seated frustration in Yousef.

“I almost weep when I think about how much of our history has been lost through carelessness, greed and even stupidity. During the early days of discovery, literally thousands of fragments were discarded or indiscriminately trampled. Look at KV55. By the time Ayrton and Davis finished their romp through that ancient mess, they had destroyed evidence which, in the hands of a modern archaeologist, would have clarified the owner’s identify and revealed more about the provenance of the artefacts found scattered around the tomb. Too late now to cry over, as you say in England, split milk.”

Liz queried “Dennis, you have been over to KV5 and 7 and observed the work of conservators? Contemporary excavation and restoration is a painstaking business undertaken by people working not to damage or overlook artefacts swept into the tombs or washed from room to room by swirling waters. Trenches are dug through the debris field and slowly widened towards walls or pillars. When found, they delicately salvage plaster that had flaked off surfaces and fallen into the detritus.”

“Surely the removal of debris from tombs like KV7 must take years, if the archaeologists are so intent in recovering every scrap of historic value?” I asked.

“Yes, it does but remember, an artefact you might regard as valueless can reveal a wealth of information to a professional. It was an assessment of fragments in flood debris that could yield clues leading to the discovery of tombs. Carter was adamant he would locate Tutankhamen’s tomb after finding artefacts bearing the king’s name amongst tomb litter.”

Yousef said “All the material excavated must be screened, as this yields a veritable treasure trove of data and, in the hands of people with our training, a range of damaged artefacts can be restored. You have seen the results in most museums.”

“So why are there so many tombs unidentified? Surely, from the sweepings left by robbers, it should be easy to determine who the original occupant was?”

“Unhappily, there are tombs devoid of images or hieroglyphs. In others, vandals or earlier explorers cleared a tomb so completely nothing was left to allow a determination. You have no idea how casual some of the early discoverers were. Intact items found their way overseas, no notes were kept, fragments were boxed then lost or shipped back home for assessments that never took place or, more usually, what was thought unimportant was shovelled out and dumped. Egyptian artefacts keep turning up all over Europe and America at boot sales, auction rooms and school fetes. Two years ago, I was in London and watched a programme called ‘Antiques in the Attic’. To my amazement, someone in Manchester wandered in with a Middle Kingdom statue he found in a garbage dump. I rang the BBC, spoke to the producer, who put me in touch the owner and I made a cash offer of £50 which he accepted. It now sits in our Museum and has been valued at over $50,000.”

“You know, we don’t regret the hours that go into conservation but knowing what is involved in the fastidious restoration of decorations creates a nightmare scenario within us - the prospect of renewed devastation by future flooding. The 1994 storm did immense damage with water depositing a new layer of silt in the lower levels of Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb. Others, including KV7,were partially flooded and the tomb of Vizier Bey was almost ruined. In Cairo, we pulled our hair out in frustration and rage. After an urgent meeting with Abdullah, the President allocated a sum for the protection of tombs, but most are still exposed to the elements. This is just one aspect of the internal battles we have over the diverse objectives associated with dollar income and the need to preserve our heritage.” he said in some anguish.

“I can appreciate the despair you must experience sitting desk-bound in Cairo.”

“Forgive me, Dennis. Sometimes I need to vent my frustration. You have no idea how irritating it is to work with the lackadaisical attitude so evident in most government departments. Palm greasing, endless inconsequential meetings and paperwork like snowflakes dogs our progress. Do know what ‘IBM’ means in an Arabic context?”

“No, I am not familiar with the idiom.”

‘Inshallah, bookra, mallish’ which literally translated, means ‘It is the Will of God, tomorrow, never mind’ or ‘IBM’. Put off until tomorrow what you can, time is unimportant.”

“I do see some of that in our local dealings.”

“Alas, some Arab attitudes are slow to change. There are times I think it is two steps forward and one step back.”

I returned to Luxor the next day. On the flight south, I reflected on the KV7 and KV5 projects. When Jean-Claude and his team chose to restore the tomb of Ramesses II, they took on a particularly difficult assignment amidst the severe damage reeked on it by at least ten major floods since its desecration. Across the wadi from KV7, Kent Weeks and his team continue the mammoth task of excavating and conserving KV5, the tomb almost beyond doubt the mausoleum of Ramesses’ sons. Exploration so far had uncovered 150 rooms with the intriguing probability of finding more. There is even a theory that a tunnel might connect both tombs.

One morning after my return, just as I was about to visit KV20, I heard my name called. Turning around, I saw an old friend walking towards our site offices. I greeted Iain with warmth and took him inside to meet Liz, who startled me by offering to make us coffee, a job she rarely undertook. I had befriended Iain McLeod at Cambridge when taking my second degree and, as we graduated together, we had kept in touch ever since. Iain returned to Edinburgh, where he secured a position with a Scottish civil engineering company who early detected his interest in working on their off-shore projects. He had project-managed for them in Australia and Kuwait.

I asked how he found me at Luxor. “I was back in London and looked up your father who told me about your work here. As I had some vacation time, I thought it a good idea to come down and see what you were mucking up in this part of the world.”

Iain’s personality lent itself to the demanding role of project management, where he combined strong technical skills with the diplomacy that is frequently required. No matter how well a project is planned, it usually gets knocked out of shape and emotions can run high in the resulting mess. He possesses the happy knack of being able to smooth the most ruffled feathers with tack, humour and aplomb. I gave him a thumbnail sketch of our activities and took him out to see the tombs, explaining the problems encountered with flood damage as we walked. He had experienced a similar environment in Kuwait and I was not surprised when he said,

“Any civil engineer would recognise the topography of the Theban Hills as nothing less than a huge natural water catchment area. Flying into Luxor, I noted a fairly flat plateau and deeply furrowed ravines with almost perpendicular escarpments, buttressed by limestone hills. Walking the ground confirms this place has all the hallmarks of a site subject to sudden cataclysmic cloudbursts, extensive flooding and considerable water management issues.”

“If you had been an Egyptian tomb builder, what would you have done?”

“Ask for a transfer to Cairo.” I laughed. “I don’t think a king held the same attitudes as a modern human resources manager. If you liked your head where it was, you obeyed instantly.”

“A bit like the Emir of Kuwait. What would I do? That’s a hard one and the answer would depend on whether or not the Egyptians recognised what we both know. Logically, the topography suggests a variety of flood control measures should have been built to divert water away from entrances. I can tell you one thing. Such measures are now imperative as what is here now is in no way adequate. There seems to be penny pinching employed in the creation of the skimpy protective barriers I see all around me.”

“I have wondered why the archaeologists themselves have not installed better protection. Our field research shows that dozens of tombs have no better protection than steel bar or wooden doors, neither of which will stop water penetration. Liz explains that archaeologists just don’t have the money in their budgets to spend on flood control though I am not sure I buy that argument. They work on sites for months at a time and a bricklayer is not a great expense in Egypt.”

Iain was only able to stay in Luxor for a few days. I showed him our work in KV20 and KV47 where he was intrigued by the isocyanate stabilisation technique, as this, he thought, was an unorthodox solution to the intractable problems of working with shale. Just before he left, I took him to lunch to discuss the possibility of his joining the next project, a prospect he said was of interest. He left with a promise to keep in touch. When I returned to the office, Liz, who had been conspicuous in her attendance to Iain and me during his visit, said “What an attractive man. He is the type of man I would like to get to know better.”

“I agree, as did his wife.”

“Dennis, sometimes you can be hateful. You didn’t tell me he was married.”

“I hadn’t realised you had more than a professional interest. I thought you were tagging along to learn more about civil works. You will just have to find solace with the Frenchmen at KV7.” For my sins, she threw a chair cushion at me. Women!

Turning my mind back to practical matters, I thought, surely ancient masons knew shale lacked the properties in which to create ideal chambers. Probably, they would have preferred to change the alignment of the tomb when it was encountered even though all royal tombs were quarried downwards towards the Underworld where, unfortunately, the Esna belt also lay. The angle of descent in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasty tombs is quite pronounced and it was only towards the middle of the Twentieth dynasty that the incline became more shallow. Not a few builders must have found themselves caught on the horns of a dilemma when they encountered an up-sweep in the shale belt. They could hardly buck convention and had to keep quarrying downwards, irrespective of the consequences. Encountering shale whilst digging tombs must have been a hit and miss business and it appears religious dogma won out against any protests a tomb architect may have wished to voice.

The tomb of King Siptah is the classic example, as the burial chamber was completely excavated into shale. There are no side chambers leading off it, indicating the builders may have decided not to proceed with further extensions due to the unsuitability of the material. Just before the chamber, a short narrow passage was quarried in a possible attempt to regain limestone until the masons inadvertently cut into the side of KV32 and had to return to the original axis. I thought it likely tomb architects, after hitting shale, continued to quarry and brought in the plasterers to cover up the friable surfaces on which decorations were to be painted. Presumably, it took a brave man to inform the pharaoh he had encountered a problem after so much effort had been expended in excavating the upper levels.

Jean-Claude d’Argent’s endeavour was considerably more onerous than ours, as we had the distinct advantage of being able to work without the severe and necessary limitations imposed by conservation, whereas he and his colleagues were excavating and preserving, whilst attempting to stabilise KV7.

Naturally, as soon as we brought our teams into the Valley, it was only a matter of days before we met. The scientific community working there are all eager to share information, discuss techniques and lend a hand with problems that required fresh insights. Our project was the subject of considerable interest and during field research my staff was willingly assisted by our colleagues. Due to earlier commitments, I hadn’t encountered Jean-Claude before the survey began so I was looking forward to meeting the man who was tackling one of the most difficult tombs. We were setting up our base within Siptah’s tomb when a tall, lean man came bounding down the steps into our work area. In his mid-fifties, he sported a neatly clipped beard, longish black hair and wore the clothes of a professional excavator - heavy boots, faded, torn jeans and T-shirt.

“I am looking for Dennis Dunlop.” he enquired with a strong French accent.

“Dennis Dunlop at your service and I would guess you are the famous Monsieur Jean-Claude d’Argent?” I responded, stretching my hand out in greeting. “Famous, non! Jean-Claude d’Argent, mais oui!” We shook hands and I introduced him to my team members.

“I have looked forward to meeting you ever since your project was approved as you have certainly selected some problematic tombs. Did these clever Egyptian devils dig around in their filing cabinets for the most difficult tombs and foist them on an unsuspecting Englishman? Just why Queen Hatshepsut built the piece of madness you wish to play in I do not know. Possibly she liked rock skiing? This tomb, he indicated with a sweep of his hands, is at least easier to work with, even if the rock at the end has all the structural stability of a chocolate éclair!”

This from a man who was grappling with a restoration every sensible archaeologist had walked away from. He told us of his background, which was more oriented towards archaeology than mine. He graduated from the Sorbonne with a Master’s Degree in History, took up a tutorial position in the Department of Antiquities and had undertaken expeditions to Bahrain, Iran and Iraq before moving to Egypt. He worked in the Valley during the winter months and returned to the university in summer to lecture and write up his research notes.

Jean-Claude impressed me as a determined and intelligent researcher with a passionate commitment to his discipline. His English was fluent and as, I had a word or two of French, our conversation flowed without difficulty and we spent an hour discussing our projects. He had to get back to KV7 but asked if I could come over to the tomb in a few days as he sought my opinion on certain matters relating to the structure. I suspect he wanted me to see what he and his associates had accomplished and was extending professional courtesy to a new colleague. He left with a promise from us that we would call in as soon as practical.

Early one morning, Richard and I sauntered over to KV7, which is not far from Siptah’s tomb. The air was still cool, none of the tourist coaches had, as yet, arrived and the only noise came from guards and workmen engaged in desultory conversation over coffee. Since the terrorist attack, the government had stationed heavily armed policemen throughout Luxor, Karnak, Deir el-Bahari and both valleys. Whilst it was, to some degree, comforting to know we worked under armed protection, it was yet another example of the sorry state certain parts of the world have slipped into in recent times.

We introduced ourselves to the policeman on guard, who called out to Jean-Claude. He emerged from the tomb’s entrance, greeted us with affection, asked if we needed some real coffee and perhaps a croissant to start our day in a civilised fashion and led us to the field office just outside the entrance where an area had been fenced off and site buildings erected. Air conditioners hummed in the background and I noted heavy cables extending into the tomb from a generator in the engineering shed. The office walls were covered with plans of the tomb, all heavily over-written with measurements and brief notations. Computers, empty coffee cups, ashtrays and files cluttered tables and the office was crammed with cabinets. It was gratifying to see the French team paid the same lack of attention to an orderly workplace as did our people.

Jean-Claude explained. “We are following a conventional project plan. In the rooms and corridors with no need of conservation, our structural engineers stabilise the walls and ceilings using techniques you would be familiar with. Elsewhere, our conservators visually inspect all surfaces for any remaining evidence of decoration. If anything is found, it is photographed in detail and copies made by our draughtsmen. When required, some very patient people work to re-attach flaking plaster where the rock is sufficiently solid to create a bond.”

“Unhappily, there is a trade-off between trying to preserve anything of a decorative nature with the engineer’s need to fit rock bolts and mesh. Inevitably, we lose some part of the decorative surface, but at least we have a record of what we may have to destroy. It can be heartbreaking watching the engineer’s drills biting into a three millennia old inscription and there is nothing attractive about metal fittings but they are a necessary evil.”

“The real challenge is excavating spaces filled with flood debris. Even though there are between seven and ten layers of debris, not many artefacts have been discovered, even at ground level. We employ Egyptians who understand careful pick-axe and shovel work as the clearing is painfully slow because the debris is set like concrete. When we strike a potentially valuable fragment, out come the finer tools of our profession. There are slabs of the original incised walls mixed in with debris and we try to recover as much as we can but it is très difficile. As we clear towards the margins, the issues become more problematic as certain large wall sections are breaking away from the rock matrix and we are forced to call in our structural men.”

“We all spent a lot of time worrying about the integrity of ceilings, especially as the limestone here is not as solid as it is in most of the other tombs. I do not know why the builder even started here or why he did not stop after seeing the nature of the rock, and make a fresh start somewhere else. I doubt the rock has changed its structure in the past three millennia and he must have worked with the same poor quality material we are trying to stabilise.”

I said “I should imagine a builder having to tell pharaoh he had made a mistake would have been a big call, especially if the king made the site selection himself. However, we believe the masons did not have the problems we both experience as Richard doubts the newly quarried limestone would not have been anywhere as fractured as it is now. By cutting into the virgin formation, masons unknowingly exposed the rock to novel forces, like compression stress and, definitely, water erosion.”

“I possibly agree with that. Add a few seismic events, several floods and the ceilings became a dangerous proposition.”

Richard advanced his pet theory. “Yes, but I think there is more to it. Egyptian limestone is pretty much the same throughout the country and I suspect that, when the builder opened this section, he did not find anything vastly different from what any of the other tomb builders found. Look at all the monuments scattered around Egypt. They are almost exclusively fashioned in limestone and they are not breaking up. At various times, they have all been saturated with rainwater but this did not cause the de-lamination we see in the tombs. Make an assumption. This tomb fills with water saturated debris. How long before it dries out?”

“Perhaps weeks or even months depending on the season. I can ask a geologist for a more definitive answer.”

“Therein may lie the answer to why KV7 is so badly damaged. It has a wide entrance, a ninety degree bend at the antechamber with half the tomb quarried down below it. There are multiple internal pier walls behind which lay the four lowest storerooms. I believe that repeated cycles of water and slow moisture evaporation lead to rock failure. Vast amounts of water poured in at various times, soaked into the existing seams and saturated the limestone for months before slowly evaporating. Whilst it was drying out, the limestone may have even steamed. The long term combination led to significant rock failure and voila. A little nightmare developed, awaiting your talents.”

“Eh bien! I will speak to a geologist to evaluate your theory.”

We finished our coffee and croissants. Jean-Claude suggested we have a look at what was going on inside the tomb, so we donned hard hats and made for the entrance. A long corridor with a double set of steps divided by a ramp led to the first gate, which had beam holes cut into it to house heavy wooden baulks placed across the passageway. Ropes, wrapped around the beams, controlled the descent of the sarcophagus as it slid down the central ramp. Passing though the gate, we entered the second sloping corridor which started out flat then reverted to split stairs, with another central ramp and more beams holes. The stairway continued through another gate and the next corridor inclined downwards before reaching a third gate and another corridor.

Jean-Claude pointed out one unusual feature - the placement of the original doors. In the majority of similar tombs, doors all swung outwards. With the exception of one gate, which had supported very heavy outward swinging wooden doors, all the other, long gone, doors had swung inwards towards the burial chamber. We came to the well shaft. Jean-Claude said “It is about six metres deep and around four metres square. We bridged it with planks to allow access to the rest of the tomb.” As we walked down, Jean-Claude pointed out the remnants of painted reliefs on the walls, which were ill defined as water and plaster de-lamination had taken a terrible toll on the decorations.

About a third the way down the length of the tomb, there is the so-called Chariot Room with its partially excavated small annexes. A divided stairway and ramp bisects the chamber, the floor was flat and the stairway flanked by two sets of pillars abutting the corridor. Debris had not been removed from behind the pillars and the walls were still largely obscured. Taking a detour, we scrambled over the debris and entered the second pillared chamber which remained untouched as there were questions about the structural integrity of the four piers supporting the ceiling. Behind it, a narrow doorway gave access to an even smaller room still filled with compacted debris.

“We have years of work ahead of us in these side chambers and I still have not decided whether it’s worth the effort. I am sure there is little of value in any of the rooms and they are, as you see, badly damaged.”

We returned to the main axis. At the end of the stairs, cut through the first pillared chamber, there is a very long double passageway. Slabs of limestone had fallen off the walls and the ceiling was reinforced with rock bolts and plates. The corridor led to the antechamber, where the tomb’s axis swung ninety degrees to the right. The walls, originally decorated with scenes from the Book of the Dead, evidence considerable surface damage with only remnants of the reliefs left. Throughout the tomb, men and women were engaged in photographing, copying inscriptions and images, restoring decorated surfaces and, of course, the ubiquitous engineers.

We entered the lower level and, despite my reading of the tomb’s condition,I was ill prepared for what lay before me. It was obvious the room had been cleared but the degree of rock failure was incredible. I looked at Jean-Claude, who could see I was perplexed.

“Mon ami, you should have seen this whole area before we started. In front of us is the sarcophagus room. It was almost two thirds full of debris with large jagged rocks, that had fallen from the ceiling, lying on the debris field. We couldn’t identify the screen walls or pillars and access to the rear chambers was just about impossible. My reaction, when I first came down here, was to walk away from the project as the destruction was so extensive. I thought ‘C’est impossible’ but what can one do? Let me walk you through the eleven rooms in the burial complex. We came in through a short narrow annexe behind us. To the right and left, there are two small storerooms and the wall behind us had five window-like apertures cut through it into the vault we are standing in.”

“Come over here to the middle of the chamber, as you will get a better perspective. The vaulted roof is six metres high at its peak, the room measures about fourteen metres square and, at the northern end, five apertures were cut, leaving four square pillars, most of which have collapsed. See at the end the remains of a stone bench? Behind it and to the left there is another small room.”

“In the vault, we found pieces of a calcite sarcophagus, very similar to Seti’s, which we suspect lay on a sculpted limestone bed. We recovered two painted lioness heads carved in limestone, which were part of a stone bed which bears a striking similarity to the complete example over in Merenptah’s tomb. There were some calcite fragments of a viscera chest originally set in a recess in the sunken floor. However, our greatest find was the blue marble figurine of Ramesses I sent up to the Cairo Museum. Apart from this little item, our collection is somewhat devoid of artefacts, all of which point to a comprehensive stripping of the tomb’s contents. As it has always been open, whatever the robbers missed was probably stolen by souvenir hunters until the first flooding buried the floor here.”

“The first robbery was during the reign of Ramesses III. Is that correct?” I asked.

“Oui, there is a papyrus documenting an attempted burglary fifty-nine years after the tomb was sealed. I find it unbelievable such an event occurred, although, Ramesses III was only two years away from his assassination and possibly the administration of the Valley was inadequate at the time. It is assumed the major pillage took place at the same time as the other tombs were robbed. The king’s mummy was moved to Seti’s tomb, then to WN-A and finally to DB320. Have you noticed the degree of savage destruction of some tomb artefacts?”

“Yes, I have thought about the reasons behind such wanton ruination. Robbers would have had to smash open a sarcophagus to get access to the coffins as the solid gold coffins would have been too heavy to lift out manually. I understand why they chopped gilt foils off coffins and funerary equipment and left the timber shell behind but that does not account for stone or ceramics being shattered. It’s not hard work to lift a viscera vessel out of its stone case. Why smash the case? I will discuss my theories with you over dinner one night.”

“I look forward to the dinner, Dennis, as I also have some thoughts on the rationale behind the vandalism. Let us continue. Behind the vaulted chamber, there are two almost identical rooms which may have been shrine rooms. Both have two pillars and stone benches. Through the eastern wall of one room, there is a narrow doorway leading to a square room devoid of pillars or benches. Off that, there is the last suite of rooms in the tomb, one slightly larger than its precursor. Two pillars supported the ceiling and it had wide stone benches on three of its walls. Eight subsidiary rooms, all of which were decorated, were apparently dedicated to the storage of royal possessions and shrines. One appears to have been for the storage of viscera jars as the figures of Isis and Nephthys flank the doorway even though there was a floor niche for a viscera chest in the main vault. We have a lot more excavation to do in these annexes.”

All the lower rooms suffered from extensive water damage and the walls and ceilings evidenced compression and stress cracking. Jagged stumps are all that remained of most pillars and there was scant evidence of what would have been spectacular wall decorations. Everywhere, the plaster originally applied to the surfaces had either de-laminated or was close to flaking off. In all, a very tragic place but the majesty of the structure is still overwhelming. After KV5, KV7 was the largest tomb in the Valley. It must have looked stunning when it was finished if compared to those of his father and his wife, Queen Nefertari. It is difficult to visualise now but it would have blazed with colour and lavish imagery.

The ceiling in the vaulted burial chamber was probably decorated in the same style as his father’s tomb, with the heavens in blue and constellations of stars, astronomic texts and rows of deities. Originally, the crypt had images of the king in the company of the principal deities amidst texts from all the Books of the Dead. The Egyptians called the burial chamber ‘The House of Gold’ and Ramesses’ must have been a tour de force of the artist’s skills.

Tomb painters had a limited range of colours. Black paint made from carbonised bones, ground chalk produced white, red came from haematite and ochre, yellow was a natural oxide, blue from a mixture of copper, iron and sand burnt together and green from a similar but more oxidised base blended with some white and yellow paint. Whilst their palette may have been restricted, the artists created some of the most vibrant and powerful images of the Ancient World.

Jeanne-Claude said “What is slightly puzzling was the total absence of broken statues of gods and goddesses and a lack of gold foil fragments. The pieces of smashed pottery and vases all seem to be poor quality work and there was not a single piece of jewellery anywhere. I would have expected to find beads, pieces of semi-precious stone or faience, bits of gold wire, lapis lazuli, anything but nothing has been found. Rather strange in the tomb of a king of his stature, d’accord?”

Now all his glory was swept away and wherever I looked I saw intrusive evidence of the engineers. Rock bolts had been used to stop further structural failure and several pillars, looking like badly decayed teeth, had been bolted through and plated. I viewed this work from a civil engineering perspective and was suitably impressed by the technical expertise of Jean-Claude’s engineers. We spent several hours inspecting the lower rooms and, when an engineer arrived with a load of rock bolts, there was some discussion on recent developments in rock mechanics and how they might be applied to tombs. The engineer was particularly interested to know how we approached repairing failed pillars and I suggested a more formal meeting with Richard, our expert in this area.

As we turned to leave the crypt Jean-Claude said “Like the Sun King in France the reign of Ramesses II marked the apogee of power, decoration and style in the New Kingdom. Everything he did was overpowering and designed to awe but look at it now. It is a catastrophe. As we would say in French, très tragique, n’est pas?” I nodded in agreement. The mausoleum would never be as attractive as the tombs that hadn’t suffered the colossal degree of damage KV7 had sustained but it would always stand as a sterling example of a Nineteenth Dynasty ruler’s monument. It is also a magnificent tribute to a team of highly dedicated scientists and technicians. As we retraced our steps we came to the boarded over well shaft.

“What have you found down there?” I asked Jean-Claude

“We have not worked in the well shaft as yet. Whatever was there originally is now ruined as the well was the first place to fill with water and it would have taken a long time for the water to either soak away or evaporate. It is not a particularly interesting part of the tomb, though we will get around to clearing it at some time.”

I congratulated him on the outstanding results, thanked him for showing us the tomb and joked about the Valley becoming our own graveyard as we both faced years of work there. His campaign was already several years old and I had just begun our projects. We expressed a hope we would meet again, both professionally and socially and over the next year, the hope was realised but I didn’t venture into KV7 again for months. When necessary, Richard visited the mausoleum for technical meetings and Elizabeth called in frequently for French lessons. I confined my meetings with the Frenchman to restaurants where we developed a close friendship.

Over one dinner, conversation turned to our ideas on tomb vandalism. I explained my theory about children indiscriminately smashing artefacts for the sheer fun of it. He didn’t think much of the idea, pointing out the Valley was a long way from Thebes. He was more interested in my ideas about mob violence. Being a Frenchman, he was well aware of the many instances of his fellow countrymen destroying buildings and objects d’art during the French Revolution and the Commune.

He disagreed. “I know about mob violence but I doubt if mobs attacked the tombs after they were first looted. It is more probable the priests recruited a body of thieves with, how do you say, ‘attitudes’. Desecrators of every persuasion attack the symbols of power of those they feel have oppressed them. Usually it is palaces, the houses of nobility, churches and, in our unique history, the Bastille in Paris. Sorry, Dennis but there was no possibility the priests or soldiers in Thebes would have permitted a mob to attack the city’s many cemeteries as they may have lost control over what they had sanctioned. That could have led to attacks on the temples.”

“It fits with the degree of destruction.”

“Yes, but a few people can do a lot of damage. If the priests recruited the robbers from amongst the ranks of those with grievances, for example, criminals sent to the royal mines, they would have gathered a fine body of desperadoes. Such men, without scruples and with, as you English say, an axe to grind, would not have baulked at the prospect of breaking into tombs, stealing everything and then venting their spleens on the remaining contents. Their reward was freedom and a percentage of the spoils.”

“That, Jean-Claude, is the most plausible explanation I have heard to date. It may have been difficult, in a religious city, to locate a gang of thieves but recruiting them from the mines and quarries would have been easy. It is anyone’s guess how long the looting took but you would need a lot of men to carry the loot out of the tombs and back to wherever it was being processed for conversion to bullion or offered for sale. There would have been furnaces to melt the gold down to bars. Imagine having to convert Tutankhamen’s solid gold coffin into bullion bars. The whole process would have been a semi-industrial venture and who better to man such an operation than a coterie of professional criminals.”

“We will never know. As there is so little evidence, this is all conjecture but the whole episode defies reasonable explanation when set into the context of Egyptian religious beliefs. Possibly, we will never determine the rationale behind a complete breakdown of traditional values but I like to believe that, when everyone involved died, Osiris fed a lot of souls to the Great Devourer.”