![]()

Keyboard Instruments

Solo keyboard music first became an independent and important genre during the seventeenth century. Keyboard instruments were used prior to 1600, of course, but the emphasis on vocal genres during the medieval and Renaissance eras, as well as the limited capabilities of the instruments themselves, consigned the keyboard to a secondary role in the musical activities of church and court. During the seventeenth century, however, a number of factors led to the creation of a large and significant body of solo works for organ, harpsichord, clavichord, and other less well-known keyboard instruments. Among these factors were the increasing emphasis on solo virtuosity and individual modes of expression, technological advances in instrument building, and various political, social, and economic changes and developments. New styles, genres, and forms appeared, and keyboard techniques were introduced that would serve as the models for succeeding generations of performers and composers. This chapter offers an introduction to this rich repertory for pianists and other keyboard players who are unfamiliar with the music and instruments of the seventeenth century, and for non-keyboard players interested in exploring the literature and performance practices of the era.

KEYBOARD PERFORMANCE PRACTICE

Make It Sing

The first step is to gain an understanding of how these instruments were played. Before embarking on such a discussion, however, it is important to emphasize that there is a guiding principle to be followed when studying and playing keyboard or instrumental music of any period: all music is vocal. Almost every aspect of musical expression uses song and speech as its model, with instruments serving as mechanical extensions of the human voice.

Stated in more familiar terms, most students, and keyboard students in particular, surely remember their teacher constantly admonishing them to “make the instrument sing!” Making an instrument sing, however, is more than merely producing a beautiful sound and a sustained line: it involves the ability to differentiate between vowels and consonants, to evoke the inflections that are natural to vocal performance and rhetorical gesture. This is particularly effective when playing the keyboard instruments of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The harpsichord, for example, with its sharp attack and noticeable termination of sound, is especially well suited for this purpose; in skilled hands it can be the most cantabile and vocal of all keyboard instruments. This intentionally provocative statement is offered here to underscore the difference between the old and newer instruments. The modern piano, a marvel of sonority and technology, is unparalleled in its ability to produce vowels within a seamless legato texture. The larger palette of articulations on the harpsichord, however, and to varying degrees on the organ and clavichord, offers the opportunities to reproduce both vowels and consonants; it can, in other words, make the instruments “sing.”

Position of the Hands, Arms, and Body

Keyboard players of the seventeenth century were as concerned about establishing the most effective way to use the hands, arms, and body as they are today. They wrote extensively on the subject, and we are therefore fortunate to be able to consult a substantial number of treatises written by the leading teachers and performers of the era that tell us much about the seventeenth century's approach to this basic issue.

One of the earliest and most important of these sources is Il transilvano (1593/1609) by Girolamo Diruta. Diruta's precepts—for he was a widely respected and highly influential figure—are mentioned and quoted in many other treatises, such as those of Costanzo Antegnati and Adriano Banchieri, and they were often recommended by composers of the period, including Diruta's teacher Claudio Merulo. Diruta is clear and explicit about the proper hand, arm, and body position to be used when playing the keyboard instruments of the seventeenth century:

To begin, the rules are founded on definite principles, the first of which demands that the organist seat himself so that he will be in the center of the keyboard; the second that he does not make bodily movements but should keep himself erect and graceful, head and body. Third, that he must remember that the arm guides the hand, and that the hand always remains straight in respect to the arm, so that the hand shall not be higher than the arm. The wrist should be slightly raised, so that the hand and arm are on an even plane…

The fingers should be placed evenly on the keys and somewhat curved; moreover, the hand must rest lightly on the keyboard, and in a relaxed manner; otherwise the fingers will not be able to move with agility. And finally, the fingers should press the key and not strike it…

This is probably more important than all else…you must keep the hand relaxed and light, as though you were caressing a child…And remember that the arm must guide the hand and must remain at the same angle as the key, and that the fingers must always articulate clearly, but never strike the keys; and lastly one finger should never be raised from the others, while one lowers the other must rise. As a final warning, do not lift the fingers too high, and above all, carry the hand lightly and with alertness.1

These principles, stated with such thoroughness and authority, became the standard for succeeding generations of keyboard players throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and within every national style. For example, the French organist Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers writes:

In order to play agreeably, you must play without effort. To play without effort, you must play comfortably. This is achieved by placing the fingers on the keyboard gracefully, comfortably, and evenly—curving the fingers, especially the longer ones, so their length is equal to the shorter ones.2

François Couperin advocated the same technique in the following century:

In order to be seated at the correct height, the underside of the elbows, wrists and the fingers must be all on one level: so one must choose a chair which agrees with this rule…Sweetness of touch depends, moreover, on holding the fingers as closely as possible to the keys.3

J. S. Bach also played in this manner, as his first biographer, Johann Nicolaus Forkel, tells us:

Seb. Bach is said to have played with so easy and small a motion of the fingers that it was hardly perceptible. Only the first joints of the fingers were in motion; the hand retained even in the most difficult passages its rounded form; the fingers rose very little from the keys…and when one was employed, the other remained quietly in its position. Still less did the other parts of his body take any share in his play, as happens with many whose hand is not light enough.4

In summary, the governing principles when playing the harpsichord, clavichord, or organ are relaxation and economy of motion, in order to achieve the maximum musical results with the minimum of physical effort. These principles, based not only on historical sources, but also on the writer's extensive experience as a performer and teacher, can and should be applied to all instruments, but they are particularly relevant to early keyboards.

Therefore, a chair should be chosen which permits the player to maintain a straight line from the elbows to the knuckles when the hands are placed on the keyboard. The arm should hang loosely and naturally from the shoulders, assuming its normal position with elbows close to the body. The wrist should be neither lower nor higher than the hand. The body should remain erect, natural, quiet, and focused.

Simply stated, the organ, harpsichord, or clavichord is played with the fingers. Contrary to the mechanics of modern piano playing, in which all the parts of the body assume an important role in technique and sound production, playing early keyboard instruments only minimally involves the forearm, arm, shoulders. The wrist is used, of course, but it should always remain supple, flexible, and quiet. The fingers should be as curved as possible, without hitting the keys with the fingernails, and they should remain as close to the keys as possible. Little is achieved by striking the keys from a distance (other than inaccuracy, coarse articulation, and a harsh sound). It is also advisable to attempt to play at the edge of the keys.

Fingering

Once the proper position at the keyboard is established, with its emphasis on finger technique, decisions must be made on how to actually use these appendages. Unfortunately, there are few discussions in the field of historical performance that have caused more controversy and confusion than those involving historical fingering. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to provide an exhaustive study of the subject, and the reader is encouraged to examine the excellent work in the field by Lindley, Soderlund, Boxall, and others as listed in this chapter's bibliography. However, a brief overview will prove useful.

The concept of “correct” fingering in the seventeenth century was derived from the theory of “good” or “bad” notes (indicating those that were metrically strong or weak), which were to be played by “strong” or “weak” fingers, respectively. Consequently, many early writers advocated the following fingering for scale passages: right hand ascending, 3434 and 3232 descending; for the left hand, the fingering was 1212 or 3232 ascending, and 3434 descending. Most commentators also usually avoided the thumb, but it would be a misrepresentation to assert that it was never used. For example, as early as 1555 the Spanish theorist Juan Bermudo suggested that right-hand scales could be fingered 1234 1234 ascending and 4321 4321 descending.5 Bermudo's countryman Correa de Arauxo concurred in 1616 but added that it would be better to use this fingering only for “extraordinary runs.”6

It is not surprising to find strong divergences of opinion about even the most basic theories of fingering, considering differences in the size and shape of hands, and in artistic temperaments, for that matter. For example, Michael Praetorius writes eloquently and forcefully in his Syntagma Musicum II (1618) about the necessity of maintaining a flexible and non-dogmatic approach:

Many think it is a matter of great importance and wish to despise such organists who are not accustomed to this or that particular fingering, but this in my opinion is not worth talking about; let a player run up and down the keyboard with his first, middle or third finger, indeed even with his nose if that will help him, for as long as it enables him to make everything clear, correct and pleasant to hear, it is not an important matter.7

The French theorist Michel de Saint-Lambert, writing in 1702 at the midpoint of two centuries of keyboard music, was in complete agreement with Praetorius. His comment on the subject reveals admirable hindsight and foresight: “There is nothing in harpsichord playing that is more open to variations than fingering. The choice must depend entirely on comfort and proper style, and will vary from player to player.”8

Players should therefore keep commentators like Praetorius and Saint-Lambert in mind when attempting to apply theories of early fingering and other performance practices in a rigid manner, and they would be well advised to avoid falling into the trap of basing musical decisions solely on historical evidence. To cite one example of this possible pitfall, some performers believe that the fingering 3434 or 3232 implies that all scale passages in seventeenth-century keyboard music should be played non-legato. This makes little sense from both historical and practical perspectives, and skilled players will discover that, with a little practice, they will just as easily be able to play legato as non-legato with such fingering. This is not to say that insights into articulation and phrasing cannot be derived from a study of early fingering. For instance, a skip of a fifth played with the same finger would preclude a legato interpretation. But in general terms, historical sources should be viewed with some skepticism and placed in the context of the wide range of all musical interpretation.

Articulation and Touch

Answers to questions about articulation and touch can be as complex and elusive as those for fingering, justifying François Couperin's reservations about commenting on the subject in his treatise L'art de toucher le clavecin: “As it would require a volume filled with remarks and varied passages to illustrate what I think and what I make my pupils practice, I will give only a general idea here.”9 Couperin is indeed correct about this, and I will follow his lead by attempting to give only a general overview on the seventeenth-century approach to articulation.

It appears that legato was the touch of choice during the period, as is apparent from the passage from Diruta cited earlier: “one finger should never be raised from the others, but while one lowers the other must rise.”10 Consequently, Diruta criticizes those organists who “take their hands off the keyboard so that they make the organ remain without sound for the space of half a beat, and often a whole beat, which seems that they are playing plucked instruments.”11 Nevertheless, détaché was not unknown to Diruta and his contemporaries, especially when playing dance music, where one can use “leaping with the hand to give grace, and air to the dances.”12

Girolamo Frescobaldi also seems to advocate legato as the basic touch. His well-known admonition to keyboard players “not to leave the instrument empty” is indicative, although he was probably referring here to the arpeggiation of suspensions and dissonances.13

It is noteworthy that Nivers, when discussing articulation, underscored the importance of following vocal models, whether playing legato or détaché:

…a sign of good breeding in your performance is a distinct demarcation of all the notes and subtle slurring of some. This is learned best from singing…That is, for example, in playing a run of consecutive notes, lift each note promptly as you play the following one…to connect the notes, it is still necessary to distinguish them, but the notes are not released so promptly. This manner is between confusion and distinction and partakes a little of each. It is generally practiced with the ports de voix…For all these matters consult the method of singing, for the organ should imitate the voice in such things.14

It would therefore be as difficult and potentially misleading to describe anything like a single touch for seventeenth-century keyboard music as it is for fingering. However, the consensus seems to be that players were expected to release the preceding note at the instant they struck the next. From this “basic legato” emanates two ends of an infinite spectrum of articulation, from a variety of détaché or silences between the notes to a hyper-slurred “overlegato” in which many and occasionally all of the notes are sustained simultaneously.15 The subtle gradations of articulation between these two extremes are impossible to measure or catalog, and their application is further modified by almost every possible variable: musical context and texture, harmonic and melodic implications, the specific instrument being used (i.e., organ, harpsichord, clavichord), individual national style, articulation symbols, ornamental figures, and rhetorical gestures.

Once again, however, the reader is cautioned against seeking absolutes in historical performance. Style was and remains an organic and evolving phenomenon. What may have been suitable for a composition written in Naples in 1625 may no longer be appropriate for one written in the same city in 1692. Or as Marie-Dominique-Joseph Engramelle lamented in 1775 when attempting to decide on a single, unchanging performance style on which to base the position of the pegs for his mechanical organs, “Lulli, Corelli, Couperin and Rameau himself would be appalled if they could hear the way their music is performed today.”16

Instruments: Organ, Harpsichord, or Clavichord

While there will always be controversy about various aspects of performance practice, the evidence about the actual instruments played during the seventeenth century is far more substantial and concrete, since a number of keyboard instruments from the period have survived and many are still playable or have been restored to good condition. Moreover, keyboard instruments were usually built within the parameters of national and even local styles, and many—particularly organs—remained in the original location in which they were used, allowing us to make reasonably certain connections between performer, composer, and instrument. Well-restored instruments from the period are valuable teachers indeed. They convey a great deal about touch, articulation, registration, use of organ pedals (if any), and other aspects of keyboard performance, thus providing aural and tactile evidence about the actual sonorities the composers heard and what it was possible to do on the instrument.

The question of which instrument to choose for a particular piece, however, is not so easily answered. Many works of the seventeenth century were written without any apparent indication as to which keyboard instrument should be used, implying complete freedom of choice; today's performers should feel equally comfortable exercising that freedom. In other instances, composers and music printers were more specific, or they at least indicated a preference for a specific instrument. Title pages and prefaces are valuable sources of information in this regard. For example, Giovanni Maria Trabaci tells us in the preface to his Ricercate, canzone francese…toccate, durrezze, ligature…Libro primo (1603) that these works might be performed on “any kind of instrument, but equally best on organ and harpsichord.”17 The fact that Trabaci reverses the order of instruments in his second book, placing cembalo first, perhaps implies that the composer changed his mind or preference.18 Trabaci does advocate only the harpsichord in his Partite sopra Zefiro (1615), claiming that “the Harpsichord is Ruler of all the instruments in the world, and one can play everything on it with ease.”19

Function is another important factor in deciding which instrument to use. Music intended for liturgical purposes typically indicates organ performance, and secular dance forms usually imply the harpsichord. The clavichord might also be used in various circumstances. It was, for example, a favorite practice instrument for organists, who could not always count on the availability of an organ blower, or who wished to avoid the uncomfortable conditions in churches during the cold months. Moreover, many pieces, both secular and sacred, were implicitly if not explicitly intended for this highly expressive solo keyboard instrument.20

Even when a specific instrument is stipulated, such as the organ, there remains the question about what type of organ should be used. Samuel Scheidt, for example, in his Tabulatura Nova (1624), asks for an organ

with two manuals and a pedal, the melody being in the soprano or tenor particularly on the Rückpositif with a sharp [i.e., piquant] stop so that one hears the chorale melody more clearly. If it is a bicinium and if the chorale melody is in the soprano, one plays the melody with the right hand on the upper manual or the Great manual and the second with the left hand on the Rückpositif.21

Johann Speth on the other hand, specified an unfretted clavichord for his Ars magna consoni et dissoni (1693): “…for the correct execution of these toccatas, praeambles, verses, etc., a good and well-tuned instrument or clavicordium is necessary, and that it should be prepared so that each clavir [key] has its own string, so that two, three or four clavir do not have to play on one string.”22

As we shall discuss later in this chapter, the choice of instrument when playing the Spanish or French organ repertory is completely unambiguous, since the titles of pieces intended for the instrument were the registrations themselves.

Surviving inventories of instrument collections are also valuable guides to instrument choice. For example, since we know that in 1600 Don Cesare d'Este owned ten organs (including one with paper pipes!) and twelve harpsichords, many with two registers, it is safe to say that any of these instruments would be appropriate for music written by the composers in service to the d'Este court.23

Tuning and Temperament

Instruments like the harpsichord and to a lesser degree the clavichord require tuning far more often than a modern piano, because of their design and the materials used to build them. This was an accepted fact of life early on, as this charming understatement from the early sixteenth-century English Leckingfield Proverbs attests: “A slac strynge in a virgynall soundithe not aright.”24 Early keyboard performers, unlike today's pianists, who rely on professional tuners to put their pianos in order, therefore need to learn how to tune their own instruments. One reason is purely financial, since it would be prohibitively expensive to hire a tuner two or more times per week. Another reason, however, is artistic: a large number of temperaments were used during the seventeenth century, and performers who tune their own keyboards have control over which system to choose for a particular composition or style. This choice can have a significant impact on realizing the maximum expressive potential of the work and the instrument.

For example, the diminished fourths found so often in Frescobaldi sound poignant in an unequal temperament, such as meantone, but lose that effect and become indistinguishable from major thirds when using a homogenous equal temperament. Likewise, certain keys take on individual characters in non-equal tunings. This is not to say that equal temperaments were unknown in the seventeenth century or should not be used for this repertory. Suggestions to divide the octave into twelve equal parts can be found as far back as Bermudo in 1555. In general terms, however, seventeenth-century composers were well aware of fine gradations in tuning and the effect of temperament on musical style. The final choice will depend on historical evidence, the nature of the instrument, the affect or character of the repertory, and the player's own ear.

(For more on this subject, see Myers's Chapter 19, “Tuning and Temperament,” in this volume.)

FORMS AND GENRES

The seventeenth-century keyboard repertory is rich in the number and variety of its forms and genres. The antecedents of many can be found in the sixteenth century or earlier, but others were newly invented or represent transformations or combinations of older forms. Since these works often carry specific implications of tempo, dynamics, character, and performance practice, it is important that the player be familiar with the nature and history of each. Although the boundaries between different forms and genres could be quite porous during this period, with the same term often being used for different types of compositions, the following brief descriptions of some of the more common will help the player get started.

Canzona

The roots of the canzona can be traced to the sixteenth-century French chanson, but it gradually became independent of vocal models, or used them in elaborate transcription. The opening was usually in imitation, often (but not always) featuring the characteristic rhythm ![]() . Connections to the fugue are present; Praetorius, in fact, describes the canzona as a series of short imitative pieces for ensembles of four or more parts.25 This principle was carried on in Germany by Johann Jakob Froberger, and the emphasis on imitation was adopted by Dieterich Buxtehude, Georg Muffat, and Johann Kaspar Kerll. It is in Germany, in fact, that we find the closest relationship between the canzona and the fugue.

. Connections to the fugue are present; Praetorius, in fact, describes the canzona as a series of short imitative pieces for ensembles of four or more parts.25 This principle was carried on in Germany by Johann Jakob Froberger, and the emphasis on imitation was adopted by Dieterich Buxtehude, Georg Muffat, and Johann Kaspar Kerll. It is in Germany, in fact, that we find the closest relationship between the canzona and the fugue.

Ricercare

The term ricercare comes from the Latin “to seek” or “to find.” Early ricercares were, in fact, often used as preludes for lute or keyboard (i.e., ricercare le corde—to try out the strings), and the most common texture was imitative. Further development of the ricercare in Germany placed emphasis on the variation principle, but the form gradually fell into disuse by the end of the century. J. S. Bach's eighteenth-century revival of the ricercare in the Musical Offering (BWV 1079) utilizes many of its stylistic characteristics, including being written in open score.

Fantasia

From the outset, the term fantasia could appear interchangeably with ricercare, preambulum, voluntary, capriccio, and canzona. It was generally written in a free, expressive style, as Thomas Morley described in 1597: “[the fantasy is] the chiefest kind of musicke which is made without a dittie…when a musician taketh a point at his pleasure, and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little of it as shall seeme best in is own conceit.”26 The fantasia became highly imitative throughout the century, however, and Italian fantasias in particular featured a variety of contrapuntal techniques. The fantasia in the hands of Jan Pieterzoon Sweelinck and north German composers remained restrained and learned.

Toccata

Performers who have spent any time improvising at the keyboard will understand the impetus that created the toccata. The name is derived from toccare—“to touch,” in Italian—and it is this act that accurately describes its nature. The most idiomatic and flexible of the early genres, it is found within all national schools and could also appear with other names, such as præambulum, prelude, fancy, or intonation. Usually written in distinct sections, the toccata could encompass a wide range of compositional techniques and stylistic traits. Brilliant passagework could be alternated with fugal sections and homophonic textures, some might be rich in rhapsodic figuration, and others were highly structured and monothematic.

Tiento

The term is Spanish, derived from tentar (to try out or experiment), but like the toccata or fantasia, the tiento could be used to describe a number of different types of compositions. For example, the twenty-nine tientos written by the sixteenth-century master Antonio Cabezón include short pieces, rhapsodic works, and highly contrapuntal compositions.

Dances

Dance occupied an important role in seventeenth-century society, and a large number of dances were written or transcribed for keyboard, usually appearing in collections called “suites.” The player therefore must understand the steps and character of all the major dances in order to arrive at the proper tempo and performance style for each. There are a number of sources to consult for this purpose, but the best method to fully grasp the nature of each is to dance it! The most common dances used by keyboard composers were the allemande, courante, and corrente; sarabande, gigue, passacaglia; and chaconne, pavane, and galliard. The reader is directed to the chapter on dance in this volume for more information about this subject.

REPERTORY

Italy

Italy produced some of the most important keyboard literature in the seventeenth century, and the player will find in this repertory an almost inexhaustible number of fine pieces to play.

Giovanni Gabrieli was one of the first major Italian composers of keyboard ricercares; he tightened the form, using fewer sections than his predecessors, and expanded the role of augmentation, diminution, and counterpoint. Adriano Banchieri continued in this tradition, as did Giovanni de Macque and Ercole Pasquini, who was organist at St. Peter's in Rome until Frescobaldi succeeded him in 1608. Their pieces in durezze e ligature style were particularly solemn compositions, distinguished by four- and five-part textures, slow harmonic rhythm, poignant suspensions, and frequent use of cross-relations and dramatic dissonances. They often employed a bold, expressive harmonic language not unlike that found in the madrigals of Carlo Gesualdo; it was so daring for the time that de Macque's student Ascanio Mayone felt compelled to justify the practice in his Secondo libro di diversi capricci per sonare (1609), explaining that some passages contained “wrong” notes “against the rules of counterpoint,” but that one should not be scandalized by them or think the author does not know the rules, since they are well observed in his ricercares.27

The Italian who towers above the rest, however, is Girolamo Frescobaldi. A keyboard player of astounding virtuosity (it was said that his art was “at the ends of his fingers”), Frescobaldi was appointed organist at St. Peter's at the age of twenty-five and became recognized as the leading and most influential keyboard player and composer in Italy.28 We find in Frescobaldi's works some of the best ricercares, canzonas, variations, and toccatas in the literature, and the performer will do no better than to play and study them all.

Frescobaldi also left us an important and enduring legacy of information about performance practice. Possibly because his was such a novel and challenging style, or perhaps because no one could play quite like him, Frescobaldi included in many of his publications explicit and detailed information about the proper performance of his music. By extension, his words can serve as a general guide for the performance of all works written in the toccata style and for seventeenth-century Italian keyboard music in general.29 One of the most complete versions appears in his Toccata e partite d'intavolatura (1637). Italics are added by the author for emphasis:

To the reader:

1. This manner of playing must not follow the same meter; in this respect it is similar to the performance of modern madrigals, whose difficulty is eased by taking the beat slowly at times and fast at other, even by pausing…in accordance with the mood or the meaning of the words.

2. In the toccatas…one may play each section separately, so that the player can stop wherever he wishes…

3. The beginning of the toccatas must be played slowly and arpeggiando…

4. In trills as well as in runs, whether they move by skips or by steps, one must pause on the last note, even when it is an eighth or sixteenth note, or different from the next note [of the trill or run].

5. Cadenzas [i.e., cadential passages], even when notated as fast, must be well sustained, and when one approaches the end of a passage run or a [cadential passage], the tempo must be taken even more slowly…

6. Where a trill in one hand is played simultaneously with a run in the other, one must not play note against note, but try to play the trill fast and the run in a more sustained and expressive manner…

7. When there is a section with eighth notes in one hand and sixteenth notes in the other, it should not be executed too rapidly; and the hand that plays the sixteenth notes should dot them somewhat, not the first note, however, but the second one, and so on throughout, not the first but the second.30

8. Before executing parallel runs of sixteenth notes in both hands, one must pause on the preceding note, even when it is a black one; then one should attack the passage with determination, in order to exhibit the agility of the hands all the more.

9. In the variations that include both runs and expressive passages, it will be good to choose a broad tempo; one may well observe this in the toccatas also. Those variations that do not include runs one may play quite fast, and it is left to the good taste and judgment of the players to choose the tempo correctly. Herein lie the spirit and perfection of this manner of playing and of this style.31

Italian composers of the generation after Frescobaldi did not reach his artistic and technical level, but they wrote attractive music nevertheless. Bernardo Pasquini was primarily a harpsichord composer, and his fine suites of dances feature sweet, simple melodies that anticipate the eighteenth-century galant style.32 Michaelangelo Rossi, a violinist who may have been a student of Frescobaldi, wrote a number of highly chromatic and attractive works for keyboard. Later in the century, Alessandro Scarlatti wrote brilliant if somewhat empty toccatas, and his harmonic language occasionally features surprising acciaccaturas that would later become a trademark in the works of his son Domenico.

Spain and Portugal

Because of geographical isolation, political events, and other factors, Spain and Portugal have always been somewhat set apart from the rest of Europe. The Spanish and Portuguese keyboard style therefore remained relatively constant and uniform throughout the seventeenth century, unlike the diverse schools of composition one finds elsewhere. Some general characteristics are contrapuntal textures, elaborate keyboard embellishment, and a penchant for variation technique. The tiento was the predominant genre.

There were several types of tientos, however, and these were usually distinguished by specific organ registrations. For example, a work titled tiento lleno was to be played on one manual, full instrument. The indication medio registro implied a divided registration, and in a tiento de medio registro de bajo the left hand played solo figurations while the right hand played chords. The ensalada (lit., salad) consisted of four or five sections alternating duple and triple meters, in the style of the Neapolitan quilt canzona. A tiento de falsas would be written in slow quarter- or half-note motion, relatively free of figuration and reminiscent of the Italian durezze e ligature style. Examples of this type of writing can be found in the works of Correa de Arauxo, who would not hesitate to sound together intense dissonances such as ![]()

![]() or

or![]()

Other Spanish composers of the period include Bernardo Clavijo, Jeronimo Peraza, and Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia. Their compositions are representative of the seventeenth-century keyboard style in Spain, including the use of uneven folk-like rhythmic patterns like 3 + 3 + 2 ![]() ). Echo passages recalling Sweelinck are also prevalent. Manuel Rodriguez Coelho's Flores de musica (1620) contains a huge repertory of over 133 works, among them tientos, versos, and Kyries. Coelho's tientos are, in fact, the longest of the century, some lasting as many as 300 measures. Notably, he suggests in his versos that each is “for singing to the organ; this voice must not be played, the four below it must be played.”33 This practice can also be found in some Italian sources.

). Echo passages recalling Sweelinck are also prevalent. Manuel Rodriguez Coelho's Flores de musica (1620) contains a huge repertory of over 133 works, among them tientos, versos, and Kyries. Coelho's tientos are, in fact, the longest of the century, some lasting as many as 300 measures. Notably, he suggests in his versos that each is “for singing to the organ; this voice must not be played, the four below it must be played.”33 This practice can also be found in some Italian sources.

Correa de Arauxo's Libro de tientos (1626) contains not only his sixty-three masterful tientos but also the treatise Faculdad organica, a valuable source of information about seventeenth-century Spanish theory and performance practice. Among the interesting points found here is Correa's advocacy of inequality in triplets. He suggests that there are two ways to play them: the first by performing the three notes evenly as written, the second by dotting the first of each group of three. Correa also shared with his Spanish contemporaries the love of complicated and uneven rhythms; one frequently finds in his music rhythmic groupings of 3 + 3 + 2 and the multi-rhythms 5 or 7 against 2 or 3. Correa would call such passages muy dificultoso (very difficult).

The major Spanish keyboard composer of the second half of the seventeenth century was Juan Cabanilles. He achieved renown throughout Spain and beyond its borders, such as in France, and his music is unjustly neglected.34 Cabanilles's output was enormous. He wrote in every genre, including tientos and toccatas, and a complete edition of his works was once estimated to require 1,200 pages. Cabanilles was a master of variation technique. Prime examples are the passacalles and paseos, such as his magnificent ground-bass variations Xácara.

The Netherlands and Northern Germany

Musical expression and practice in the Netherlands and northern Germany reflected the influence of the Reformation and the Protestant church. Instead of the rhapsodic keyboard style and wide range of affect in the south, the keyboard music of northern composers was often more sober and tightly structured, using the Protestant chorale and English variation technique as unifying principles, and favoring sequential patterns supported by relatively conservative harmonies. The major figure of the early part of the century in the north was Sweelinck. He established almost every genre that would be used in Germany throughout the era, and his contributions to each reveal a masterful composer. His works based on the chorale were written in several different styles, such as the bicinium (cantus firmus in one hand accompanied by left-hand figures), the tricinium (cantus firmus in inner voice with figuration in outer voices), and the chorale motet. His ornamented chorale settings, in which the cantus firmus serves as the foundation for extensive melodic embellishment, were particularly influential, since from these works develop the German organ tradition of choral prelude and choral variation. Indeed, much of Sweelinck's music was intended for organ performance, but there is also an excellent body of harpsichord music, such as his keyboard variations Est-ce Mars and Mein Junges Leben hat ein End', that clearly falls under the sphere of the English virginalists. Sweelinck was very familiar with this repertory and knew several of the virginal composers personally, including Peter Philips and particularly John Bull, who lived in the Netherlands for much of his life.

Sweelinck was acquainted with other Dutch contemporaries, such as Pieter Cornet and Henderick Speuy, but his true followers were German. Sweelinck was in fact called “the teacher of German organists,” and his students included composers such as Jacob Praetorius, Heinrich Scheidemann, and Samuel Scheidt. This generation of organist-composers continued the work of their Dutch master and firmly established the North German organ school—that is, a conservative style based on the Protestant chorale, but one of grandeur and power that expanded and exploited the full resources of the organ, especially by the use of virtuoso pedal technique, echo effects, and registration. Scheidt shared his teacher's penchant for variation technique and wrote partitas on many of the same melodies used by Sweelinck, including Est-ce Mars and Fortuna. Scheidemann established Hamburg as the center of organ music from 1620 to 1645 and made major contributions to the setting of the chorale.

The next generation in northern Germany included Franz Tunder, Mathias Weckmann, George Böhm, and Buxtehude. Tunder began to soften the severity of the style with displays of keyboard virtuosity. His works would often begin and end with dramatic sixteenth-note runs, and double pedal writing and other virtuoso footwork were not uncommon. Böhm's music reflects the growing influence of Italian opera and the French style in Germany, particularly in his harpsichord works, which feature many French characteristics, such as the use of style brisé (broken style) and French-style ornamentation. The major figure in this group was Buxtehude, whose work represents the culmination of seventeenth-century German organ music. His chorale fantasias are rich in keyboard effects and independent, virtuosic pedal parts, and they can include both strict counterpoint and gigue-like sections. Buxtehude gradually abandoned the chorale-based compositional style in favor of freer forms, such as the præambulum, in which he could use a wider range of tonalities and have greater freedom for technical display.

Central and Southern Germany

It is not surprising that the influence of Italy and France would have been more strongly felt in the nearby central and southern parts of Germany, where the Catholic faith was predominant. To be sure, central German composers such as Johannes Kindermann and Johann Pachelbel remained dependent on the Protestant chorale and wrote a large number of chorale settings, but their preludes and toccatas could resemble the rhapsodic style of Frescobaldi. Pachelbel contributed six excellent variations based on secular and original themes in the Hexachordum Apollinis (1699), and three of his six chaconnes are for the harpsichord; the other three require organ pedals, although the pedal writing of these composers rarely approaches the virtuosity of the north. Other southern and central German masters include Johann Ulrich Steigleder, Christian Erbach, and Hans Leo Hassler, who studied with Andrea Gabrieli in Venice and became organist for the fabulously wealthy Fugger family. Hassler's ricercars are of great interest and considerable length. Later generations include the Francophile George Muffat, who studied with Jean-Baptise Lully in Paris. Muffat's excellent Apparatus musico-organisticus (1690) contains twelve toccatas, a passacaglia, and a chaconne. The adventurous keyboard player with a sense of humor might well investigate the music of Alessandro Poglietti. He wrote some of the most bizarre and individual program music of the century, primarily for harpsichord. One such piece, the Aria Allemagna (1677), attempts to depict such “bizaries” as the “Bohemian Bagpipe,” “French Hand-Kisses,” and the “Polish Saber Joke.”

The dominant figure in this part of Germany, and elsewhere, was Johann Jakob Froberger. A student of Frescobaldi in 1641, Froberger traveled widely. He lived in Vienna, visited Dresden, Brussels, Utrecht, Regensburg, Paris, and London, and created an inspired synthesis of Italian, German, and French styles in his keyboard music. Because of his friendship with the French lutentist Denis Gaultier and the claveciniste Louis Couperin, Froberger exerted a strong influence on the early French clavecin style, and he in turn was influenced by it. The musical connections are nowhere more evident than in Louis Couperin's Prélude a l'imitation de Mr Froberger, in which Couperin pays homage to his German colleague by transcribing the opening of Froberger's Toccata I in A Minor into the whole-note unmeasured notation of the seventeenth-century clavecinistes.

Example 14.1a. Johann Jakob Froberger, Toccata 1 in A Minor, mm. 1–3.

Example 14.1b. Louis Couperin, Prélude à l'imitation de Mr. Froberger (excerpt).

Both Louis Couperin and Froberger also wrote poignant tombeaux for harpsichord on the death of their mutual friend Sieur de Blancrocher (i.e., Charles Fleury). It is, in fact, as a harpsichord composer that Froberger made his most significant contribution to seventeenth-century keyboard music. Pieces such as his Lamento sopra la dolorosa perdita della…Ferdinand IV and the Tombeau plumb the depths of the expressive potential of the instrument, and Froberger was also responsible for the establishment of the harpsichord suite in Europe. His early works in this genre consisted of allemande, courante, and sarabande, but the gigue was soon included, appearing directly after the allemande.

England

The great Elizabethan tradition of keyboard composition as represented by composers such as William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, and Giles Farnaby was not sustained during much of the seventeenth century. The establishment of the Commonwealth ultimately suppressed musical growth in England, particularly that of the organ, and this was admittedly not a rich period of keyboard composition in the British Isles. For example, Bull left his native country because of this unfavorable musical climate and ultimately settled in Antwerp in 1613, to the delight of Sweelinck but to the detriment of the English.

Keyboard composition was revived in England after the Restoration, but with thinner textures, simpler melodies, and fewer dances of the old style. For example, Elizabeth Rogers’ Virginal Book (1656/57) contains no pavanes and galliards, but rather simple binary almans and corants. The French influence is also now felt more strongly in English music from this period, and the suite begins to take prominence.35 Thomas Mace described the genre in 1676:

A Sett, or a Suit of Lessons…may be of any Number…The First always should begin [with] which we call a Prealudium or Praelude. Then, Allmaine, Ayre, Coranto, Seraband, Toy, or what you please, provided They be all in the same Key.…36

The first published keyboard music of John Blow and Henry Purcell appears in the second part of Musick's hand-maide (1689). Blow had assimilated the German and French styles by copying music of Froberger and others. Purcell is represented in this volume by thirteen pieces and a suite. Eight of his suites and six miscellaneous pieces were published posthumously in 1696 as A Choice Collection of Lessons. Although Purcell's genius and melodic gift are in evidence, his contributions to the keyboard repertory do not represent him at his most inspired or profound.

The Choice Collection does, however, contain Purcell's “Instructions for Learners,” an important source of information about his performance practices and those of Purcell's contemporaries, both in England and on the Continent. In these “Instructions” we find realizations of Purcell's ornament signs in the “Rules for Graces,” and interesting insights into the tempo and character that can be determined by various time signatures. For example, Purcell tells us that:

Common time…is distinguish'd by three signs: ![]() or

or ![]() ; ye first is a very slow movement, ye next a little faster, and ye last a brisk and airry time, & each of them has allways to ye length of one Semibrief in a barr. Triple time consists of either three or six Crotchets in a barr, and is to be known by

; ye first is a very slow movement, ye next a little faster, and ye last a brisk and airry time, & each of them has allways to ye length of one Semibrief in a barr. Triple time consists of either three or six Crotchets in a barr, and is to be known by ![]() , 3, or

, 3, or ![]() To the first there is three Minums in a barr, and is commonly play'd very slow, the second has three Crotchets in a barr, and they are to be play'd slow, the third has ye same as ye former but is play'd faster, ye last has six Crotchets in a barr & is Commonly to brisk tunes as Jiggs and Paspys [passepieds].37

To the first there is three Minums in a barr, and is commonly play'd very slow, the second has three Crotchets in a barr, and they are to be play'd slow, the third has ye same as ye former but is play'd faster, ye last has six Crotchets in a barr & is Commonly to brisk tunes as Jiggs and Paspys [passepieds].37

One of the more confusing aspects of seventeenth-century English music is the terminology used for plucked keyboard instruments, and in particular the term “virginals.”38 For example, the title pages of Parthenia (1612) and Parthenia in-violata (1625) refer only to “the virginalls,” but that of Musicks hand-maide advertises “lessons for the virginalls or harpsycon.” Many other names can be found, as well. We read of “Espinettes,” “Clarycordes,” “Harpsicon,” and “Harpsicalls”; “Clavecymbal” is defined as “a pair of Virginals, or Claricords” by Thomas Blount in his Glossographia (1656).39

The spinet is another keyboard instrument that became common in England during this time, and the term appears alongside “harpsichord” and “virginals.” It was especially popular with the middle class, because of its small size and relatively low cost. For example, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on April 4, 1668, that he had decided to buy a spinet because “I had a mind to a small harpsichon, but this takes up less room, and will do my business as to finding out the chords.”40

A number of foreign instruments were imported to England, especially those built by the Flemish Ruckers family and the Franco-Flemish Jan Couchet. In 1710, for example, it was reported that the Romer tavern in Gerard Street housed

two matchless clavearis, which are considered the best in the whole of England…They are over 100 years old and were built by two of the most famous masters in Antwerp. The best was made by Hans Ruckers and the other by his son Jean Rucker…Both have double-keyboards.41

The Daily Courant of February 3, 1713, advertised “Two extraordinary Harpsicalls…made by the same Hand as What Mr Roselli has sold here in the Name of Couchet.” The only surviving British harpsichord from the seventeenth century is a one-manual instrument with the registration of two eight-foot stops and lute by Charles Haward (1683).

France

ORGAN MUSIC

The difficulty in determining which work was written for organ and which for harpsichord is not an issue when we turn to French keyboard music. Like the Spanish before them, composers in France made a clear and unambiguous distinction between the two instruments: harpsichord music was designated by the term clavecin, and almost every piece of French organ literature carries the name of a specific organ registration (e.g., Duo, Cromorne en taille, Dialogue sur les grand jeux, Plein jeu, etc.). This tradition appears early on in France, the first example being a manuscript from 1610 with pieces titled Pour le cornet and Pour les registres coupez. Also similar to Spain, each French registration/title implied a specific compositional style and character. For example, a plein jeu piece called for the full organ registration (e.g., grand orgue, positif and mixtures) and would be written in the durezze et ligature style. A petit plein jeu piece would feature more figuration in sixteenth notes. A récit de trompette implied that the melody, often treated in fugal fashion, was played on the indicated stop and accompanied by flutes or other appropriate registrations. Its rhythm and character was usually that of a bourée or gigue.

The earliest master of French organ music was Jean Titelouze. His two published works, Hymnes de l'église (1623) and Le Magnificat (1626), are generally conservative and dependent on Gregorian chant, with a strict cantus firmus technique and a polyphonic texture. Other followers of Titleouze include Charles Racquet and Étienne Richard. François Roberday attempted to introduce some Italian elements into French organ music and even included works of Froberger, Frescobaldi, and Wolfgang Ebner in his Fugues et caprices (1660). By mid-century, the increasing popularity of opera, dance, and chamber music could not be ignored; organists began to favor simple textures and elegantly ornamented melodies, while never completely leaving the older style. Some of the major publications of organ music include books by Nicolas Gigault, who still wrote serious liturgical music but employed rapid manual changes and a high degree of ornamentation. Nicolas Lebègue wrote three Livres d‘orgue, consisting of Masses, noëls with variations, dances, and symphonies. André Raison, the teacher of Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, was also a valuable commentator on style; the theme of his Trio en Passacaille bears a strong resemblance to Bach's Passacaglia in C Minor (BWV 582). Nivers was said to have written with “detachment and easy grace” and contributed over one hundred compositions in the church modes. Nicolas de Grigny wrote perhaps the last Livre d‘orgue of the century in 1699, and several of these works were copied by Bach.

HARPSICHORD MUSIC

The music of the les clavecinistes (as they were called in France) represents the most idiomatic harpsichord music of the seventeenth century, and arguably the best. The origins of this repertory can be found in the works of the Joueurs d'épinette of Louis XIII, such as Nicolas la Grotte and Jacques Champion. Stylistic traits are shared with the French lutenists, such as an emphasis on dance movements, extensive ornamentation, and the improvisatory prelude.

In the clavecin style, a two-voice texture predominates, featuring an elegant, richly ornamented melodic line and a simple accompaniment. Intricate contrapuntal writing or chorale-like homophony is avoided, and fugues, ricercares, fantasias, and sonatas are rare. The French harpsichord composer achieved maximum expressive effect by the resonant spacing of parts, a sensitive use of sonorities, and a rich harmonic language. Virtuoso keyboard displays were also kept to a minimum.

Two of the most distinctive features of the style are the style brisé and its prolific ornamentation (i.e., agréments). Players might at first be astonished by the number and variety of ornaments in this repertory, and contemporary writers often expressed dismay at their profusion.42 However, this is not ornamentation in the sense of divisions or embellishments, and the manner in which it is used distinguishes it from all other Baroque keyboard music. The ornaments here are decorations of the melody like the additions to French furniture of the period. More importantly, they are meticulously notated and applied to create a wide range of nuance, color, and dynamics on the harpsichord. These agréments are not optional or improvisatory, but become an integral part of the composition. One need only play a French melody with ornaments removed to fully understand their crucial impact on the music, and it is advisable to learn a piece this way. Since most composers developed their own personal system of notation, the player should carefully study the table of ornaments usually found at the beginning of each published work.

The style brisé or style luthée indicates a style of arpeggiated writing that creates a rich texture of sonorities and implied polyphonies. As the name implies, the style luthée recalls lute practice, and the technique is idiomatic to no other keyboard instrument but the harpsichord.

The ascent of Louis XIV to the throne in 1643 was a pivotal moment in the history of French music and signaled a dramatic change in the society and culture. Lutentists and joueurs d'épinette receded into the background, and their intimate, small-scale pleasures were replaced by grandeur and majesty. As Titelouze wrote to Mersenne: “I remember having seen in my youth everybody admiring and being delighted by a man playing lute, and badly enough at that…now I see many lute-nists more skilled than him who are hardly listened to.”43 La Fontaine lamented in 1677 that “the time of Raymon and Hilaire is past: nothing pleases now but twenty harpsichords, a hundred violins.”44

The clavecinistes would attain a central place in the court of the Sun King and produce one of richest repertories in the history of harpsichord music. The tradition and style remained fairly consistent for almost two hundred years, reaching its culmination with François Couperin and continuing into the last years of the eighteenth century with the death of Claude Balbastre.

Masterpieces of seventeenth-century French repertory were written by Jacques Chambonnières, Louis Couperin, and Jean-Henri d'Anglebert, and many fine works will be found in the books of Pièces de clavecin by composers such as Henri Dumont, Lebègue, Jacques Hardel, Clérambault, and Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre.

In addition to the proper realization of the ornaments, style brisé, and other aspects of performance practice, two features of French keyboard music pose considerable challenges to the early keyboard player and deserve special mention here: inégalité and the improvisatory prélude.

As we have seen in our discussion of Frescobaldi, Correa de Arauxo, and others, performers of seventeenth-century keyboard music were often allowed and sometimes obligated to alter the notated rhythm. The principle of inégalité in French music, however, is unique to France and remains one of the most misunderstood concepts in all of performance practice. This was also true during the period in which the music was written and performed, as François Couperin so aptly put it in L'art de toucher le clavecin: “We write differently from the way we play, which is the reason why foreigners play our music less well than we play theirs.”45

Inégalité refers to the technique in which passages written with equal note values are performed in unequal rhythm, according to a number of clearly defined rules. There is no disagreement that it was standard in the performance of French music.46 Numerous sources corroborate this fact, such as Saint-Lambert, who writes that “the equality of movement that we require in notes of the same value is not observed with eighth notes when there are several in a row. The practice is to make them alternately long and short, because this inequality gives them more grace.”47

Other sources are equally definitive. Nivers writes in 1665 that

there is yet another special sort of mouvement, fort guay, which is to make as though half-dots after the 1st, 3d, 5th, and 7th eighth notes…that is to say, to augment ever so slightly the aforementioned eighths, and to diminish ever so slightly in proportion those that follow…which is practiced according to discretion, and many other things which prudence and the ear have to govern.48

Bénigne de Bacilly added in 1668:

Although I say that in diminutions there are dots, alternate and assumed, which is to say that of two notes, one is ordinarily dotted, it has been deemed appropriate not to mark them, for fear that tone one might accustom himself to execute them by jerks…[notes inégales should be executed] so delicately that it is not apparent.49

The concern over playing inégal by “jerks” (i.e., excessively dotted) was considerable. The viola da gambist Jean Rousseau warned in 1687 to “take care not to mark [passages played unequally] too roughly.”50 It is also important to remember that inégalité applies only to stepwise motion; skips are played equally. This is confirmed by Michel Pignolet Montéclair: “Notes in disjunct intervals are ordinarily equal…it is necessary to distinguish this inequality of which we are speaking from that which requires the dot, which is greater.”51

It is, however, the degree of inequality that has led to such confusion and misinterpretation. The most common misconception is that inequality implies the creation of uniform dotted rhythms. Although such dotting is, to be sure, a possible realization, it is only one of an infinite range of rhythmic interpretations (and a rare one at that). Composers were certainly able to notate such dotted rhythms clearly and without ambiguity, and they appear side by side with evenly notated passages.

To correctly understand inégalité, one must realize that it is really a highly refined rubato, an expressive device that must be applied with subtlety and artistry; its very nature is such that it cannot be notated. This becomes clear from the internal evidence of the music itself and from the written sources, as well. For example, Saint-Lambert writes: “It is a matter of taste to decide if they should be more or less unequal. There are some pieces in which it is appropriate to make them very unequal and others in which they should be less so. Taste is the judge of this, as of tempo [author's italics].”52 Therefore, the use of inégalité defies a strict or simple mathematical realization but demands of the performer the widest range of subtle expression, based on the character of the piece and on bon goût (good taste).

Inégalité essentially remained within the borders of France. Composers of other nationalities were certainly aware of its existence, but it is dangerous to assume that it should be applied to their music unless these non-French composers indicated it specifically or were consciously writing in the French style.

UNMEASURED PRéLUDE

Every nationality has a genre that is improvisatory in nature. For example, the Italian toccata and the German præambulum allow the player considerable rhythmic and expressive freedom. However, the notation of French preludes, which are written either completely in whole notes without any rhythmic indication, or with a mixture of rhythmic and non-rhythmic notated values, makes the genre particularly difficult to decipher and interpret. The French were aware that this style of composition and notation might present problems for inexperienced or foreign players. Lebégue wrote:

I have tried to present the preludes as simply as possible, with regard to both conformity [of notation] and harpsichord technique, which separates [the notes of] or repeats chords rather than holding them as units as is done on the organ; if some things are found to be a little difficult or obscure, I ask the intelligent gentleman to please supply what is wanting, considering the great difficulty of rendering this method of preluding intelligible enough for everybody.53

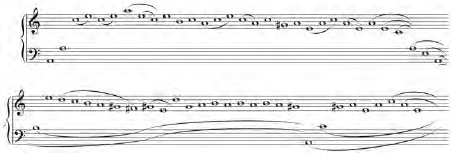

Almost every French composer contributed works to this genre, from the beginning of the seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth, and they used a wide variety of notational systems. Those of Louis Couperin are the most ambiguous, written entirely in whole notes with a forest of wavy lines (see Example 14.1b above). Other composers, such as Clérambault, added occasional rhythmic figures, dotted lines to indicate the simultaneous striking of two or more notes, and ornamental signs. Nevertheless, one should use the same musical approach when performing the French prelude, regardless of individual systems of notation. Players should become familiar with the available information regarding performance practice and notation. They should make a thorough harmonic analysis of the piece, and it is often useful to write a figured bass for it whenever possible. A decision should be made as to which notes are melodic and which represent passing tones or ornaments. A familiarity with other improvisatory styles is advisable, and a comparison with toccatas and pieces marked à discretion will be invaluable, particularly those of Froberger. As we have seen in our comparison of Froberger's Toccata and Louis Couperin's Prélude (see Examples 14.1a and 14.1b above), Froberger's notation appears more regular, but the freedom of execution is no less than that which one would use for the French repertory.

F. Couperin speaks to the heart of this matter and to musical interpretation on the keyboard in general: “play [these preludes] without attaching too much precision to the movement; at least where I have not expressly written the word measured; thus, one may hazard to say that, in many ways, music (compared to poetry), has its prose and its verse.”54

NOTES

1. Diruta, Il transilvano; see also Rodgers, “Early”: 278–280, and Soderlund, “How”: 68–77. It is interesting to note that Diruta's approach is diametrically opposed to that of an earlier, equally famous theorist, Tomás de Santa Maria, who advocated “that the hands be placed hooked, like the paws of a cat, in such a manner that between the hand and the fingers there will in no way be any curvature; instead, the knuckles have to be very sunken, in such a manner that the fingers are higher than the hand [and] arched. And thus the fingers remain more pointed, so as to strike a greater blow.” Santa Maria, Libro: 37, trans. here, Rodgers, “Early”: 219.

It should be added that although Santa-Maria remains an instructive and valuable source, the reader should be cautioned that the early date of his treatise makes it more applicable to mid-sixteenth-century keyboard style than to the very different repertory and instruments of the seventeenth century. It is also noteworthy that the Spanish theorist often refers to the early clavichord: “The fifth thing is to press the keys down as far as they will go conveniently, so that if the instrument is a clavichord, the tangents will raise the strings properly; moreover, in such a way that the voices will not depart from their pitch by sharping.” Santa-Maria, Libro: 32, trans. in Rodgers, Early Keyboard Fingering: 223.

2. Nivers, Premier, trans. in Nivers/Pruitt, Organ: 158, and cited in Soderlund, How: 98.

3. Couperin/Halford, L'art: 29 and 31. Online reproduction available at http://www.free-scores.com/download-sheet-music.php?pdf=3163

4. Forkel/David-Mendel, Über: 308; Forkel/Wolff, Über: 432–436.

5. Bermudo, El libro: cited in Sonderlund, How: 36.

6. Correa de Arauxo, Libro: 23–24ff; cited in Lindley, “Renaissance”: 197.

7. Praetorius, Syntagma II: 44; Praetorius/Crookes, Syntagma II: 53; Kroll, Playing: 49.

8. Saint Lambert/Harris-Warwick, Les principes: 70.

9. Couperin/Halford, L'art: 31.

10. Once again, Santa Maria holds an opposing view: “THe finger that strikes first is always raised before the one that immediately follows it strikes.” In other words, détaché. Santa-Maria, Libro, trans. in Rodgers, Early: 225.

11. Diruta, Il transilvano I, fol. 5v, trans. in Hammond, Girolamo Frescobaldi: 232.

12. Diruta, Il transilvano I, fol. 5v, trans. in Hammond, Frescobaldi: 232.

13. For a full discussion, see Tagliavini, “The Art”: 299–308.

14. Nivers, Livre d'orgue, trans. in Pruitt, The Organ: 162, cited in Soderlund, How: 98.

15. An excellent description of “overlegato,” notably for both conjunct and disjunct motion, is provided by Saint-Lambert, when explaining the execution of the port de voix: “The pen stroke drawn above the notes in the realization of the port de voix is a slur, which means it is necessary to run those notes together, that is to say that one must not raise the fingers while playing them but wait until the second of the two notes is played before raising the finger that played the first one.” Saint-Lambert/Harris-Warwick, Principes: 86. This technique should also be conservatively applied to the organ! Both Nivers and André Raison in the preface to his Seconde livre d'orgue (1714) advocate it. Overlegato can also be applied to Beethoven performance on the piano. See Kroll, “As If Stroked”: 129–150.

16. Engramelle, La tonotechnie, cited in Veilhan/Lambert, The Rules, Introduction.

17. Trabaci, Ricercate, cited in Apel/Tischler, The History: 439.

18. Trabaci, Il secondo, cited in Apel/Tischler, The History: 439.

19. Cited in Apel/Tischler, The History: 439.

20. Some of the factors that would indicate the use of the clavichord include written instructions in the preface or title page, notated signs for Bebung (vibrato), musical texture, and the purpose and location of the performance.

21. Scheidt, Tabulatura, preface to vol. III (author's trans.).

22. Speth, Ars magna, preface, cited in Apel/Tischler, The History: 582.

23. Hammond, Frescobaldi: 103.

24. Harley, British: 151.

25. Praetorius, Syntagma III: 17; trans. in Praetorius/Kite-Powell, Syntagma III: 32.

26. Morley, A plaine: 180; Morley/Harman, A plaine: 296; cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 209.

27. Cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 429.

28. Frescobaldi was occasionally not averse to blatant and humorous displays of keyboard showmanship. Hammond tells us that he would sometimes entertain his friends by playing the keyboard with his hands reversed, palms upward. Hammond, Frescobaldi: 28, citing Antonio Libanori, Ferrara d'oro imbrunito (Ferrara, 1665–74), par. 3.

29. Other Italian composers wrote about the performance of various forms and genres, such as Adriano Banchieri in his Moderna armonia (1612), who tells us that repeated sections of canzoni alla francese “must be played adagio the first time as in a ricercare [author's italics], and in the repeat quickly.” Cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 417.

30. Other contemporary writers recommended playing eighths and sixteenths in this manner, particularly in fast movements, “as if they were half dotted,” implying a generally accepted practice of the period. See, for example, Scipione Giovanni, Intavolatura di cembalo, et organo (Perugia, 1650), preface, reproduced in Sartori, Bibliografia: 411–412.

31. Frescobaldi, Toccate (1637); preface, trans. in Apel/Tischler, History: 456 (see also 448–449 for a listing of his works). The advice given here also appears in Frescobaldi's Toccate e partite d'intavolatura di cimbalo, Libro primo (1615, rev. 1616, 1628), Il secondo libro di toccate (1627), and Fiori musicali (1635).

32. Pasquini still felt the influence of Frescobaldi. He purchased the first book of toccatas (1628 edition) in 1662, often quoted from it, and recommended Frescobaldi as a teacher.

33. Cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 525.

34. Cabanilles's student Joseph Elias (ca. 1722) would write that “the world may vanish before a second Cabanilles comes.” Cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 771.

35. The music of the lutenist Denis Gaultier was well known in England, and Jacques Gautier (d. before 1660) and the renowned Richard family were in residence at the English court.

36. Mace, Musick‘s : 120, cited in Harley, British: 85. A fine collection of suites by several different composers was published in Locke, Melothesia (1673), which also included a list of English ornaments.

37. This information can be found in a number of sources, including Purcell, A Choice, Harley, British: II, 219, MacClintock, Readings: 156, and Playford, An Introduction: 75–78.

38. References to “a pair of virginalls” appear in English documents as early as 1517.

39. Cited in Harley, British: II, 152–153.

40. Pepys, Diary: 149.

41. Z. C. von Uffenbach, London in 1719, from the Travels of Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach, trans. by W. H. Quarrell and Margaret Ware (London, 1934), 181–182, cited in Harley, British: II, 165.

42. The eighteenth-century commentator Charles Burney, for example, voiced the following reservation upon hearing the music of F. Couperin: “his pieces are so crowded and deformed by beats, trills, and shakes, that no plain note was left to enable the hearer of them to judge whether the tone of the instrument on which they were played was good or bad.” Burney, A General History: 996.

43. Mersenne, Correspondance: vol. I, 75; cited in Ledbetter, Harpsichord: 8.

44. Jean de La Fontaine, “Epître à M. de Niert sur l'opéra” in Oeuvres diverses: vol. 2 (Paris, 1677, rep. Paris, 1958), cited in Ledbetter, Harpsichord: 13.

45. Couperin/Halford, L'art: 49.

46. The earliest account of French-style inequality is documented by Loys Bourgeois in 1550: “The manner of singing well the (quarter-notes) is to sing them two by two, dwelling some little bit of time longer on the first, than on the second.” Hefling, Rhythmic: 3.

47. Saint Lambert/Harris-Warwick, Principes: 46.

48. Nivers, Premier: 114, cited in Hefling, Rhythmic: 5.

49. Bacilly/Caswell, Remarques: 232, cited in Hefling, Rhythmic: 6.

50. Rousseau, Traité: 114, cited in Hefling, Rhythmic: 7.

51. Montéclair, Nouvelle:15, cited in Hefling, Rhythmic: 13.

52. Saint Lambert/Harris-Warwick, Principes: 46.

53. Lebègue, Pièces, cited in Apel/Tischler, History: 714.

54. Couperin/Halford, L‘art: 70.