![]()

Plucked String Instruments

THE LUTE

During the sixteenth century, the tuning, stringing, and construction of the lute remained remarkably consistent from one country to the next, with the exception of the vihuela in Spain, with its waisted design. The basic six-course instrument, tuned fourth-fourth-third-fourth-fourth, was played all over Europe for most of the century, with only subtle variations in stringing and construction practiced in different regions. In the seventeenth century, however, each country took its own approach to the instrument, resulting in new tunings, playing techniques, and types of lutes. In fact, the whole concept of how the lute should be used and what kind of music should be played upon it took radically different turns in different parts of Europe. To understand this development more easily, we will consider each country individually.

Italy

The trend in the late sixteenth century was to add bass strings to the lute to provide a more sonorous low register and to make playing in some keys easier. This trend continued in the seventeenth century, with the addition of an octave of diapasons to complement the original six courses, which were still tuned in the Renaissance fashion. The extra bass strings required changes in the construction of the instrument, since they would have been too thick to make a satisfactory sound at the length of the fingered strings. Thick gut strings produce a dull, muddy tone, so that for gut-strung instruments, longer string lengths are preferable since thinner strings can be used. The process of wrapping strings with silver or copper wire was not invented until after 1650. This invention allowed instrument makers to produce shorter instruments which had the same bright clear tone in the middle and bass registers as the longer instruments of the first half of the century.1 In order to use long, thin strings for the basses, a new design was necessary, involving two different string lengths, one short enough to facilitate easy reach of chords with the left hand, the other long enough for thinner strings to be tuned to the appropriate low pitches. Alessandro Piccinini had an instrument built in which the body was twice as long as that of a normal lute, with a second bridge on the soundboard to accommodate the bass strings.2 He admitted that the two sets of strings produced quite different timbres, since the basses were plucked in the middle of the string, while the trebles were plucked near the bridge.

The solution, Piccinini soon discovered, was to extend the neck, adding a second pegbox to accommodate the diapasons, which allowed all of the strings to be fastened to one bridge, thereby equalizing the resistance of the strings at the point of attack. This instrument, known as a liuto attiorbato (theorboed lute) or arciliuto (archlute), became the standard Italian lute of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was popular both as a solo and as a continuo instrument. The of-quoted remark by Vincenzo Giustiniani in 1628, that the lute was no longer played in Italy, must refer to the old Renaissance lute, since the archlute figures very prominently in iconography, accounts of performances, and surviving music of the time—so much so that it became unnecessary to specify “archlute” and the word liuto was used to refer to the extended-neck variety for most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The other Italian lute of this period was the chitarrone, or tiorba (theorbo) as it was often called.3 It was invented in the late sixteenth century as an instrument to accompany singers in the theater, a task that required more projection than most Renaissance lutes were capable of. This was accomplished by tuning the strings of a bass lute up a fifth and replacing the first two strings, which broke at the higher pitch, with thicker strings tuned an octave lower. The octave displacement of these strings was not a problem, since the instrument was invented to provide simple chordal accompaniments and the octave of the individual notes did not matter. At first simply a new way of tuning a bass lute, the chitarrone eventually had an extended neck added to it, providing an octave of bass strings for it as well.4 Piccinini also claimed credit for this invention, adding that the contrabbassi—strings of the sixteen-foot register—give the instrument its true character. Written continuo lines in seventeenth-century music rarely make use of these notes, but it is clear from surviving realizations and solo works that theorbists routinely dropped bass lines down an octave in order to make use of this most sonorous part of the instrument.5 In Bologna, Maurizio Cazzati listed the tiorba as one of the instruments to play from his contrabbasso partbook. As Examples 17.3 and 17.4 in the “Basso Continuo” chapter show, the bass line may either be dropped an octave for several notes in a row, or the written bass note may be restruck an octave lower to provide greater sonority.

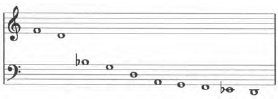

Michael Praetorius and Piccinini mention the use of metal strings on the chitarrone, though gut seems to have been more common.6 It is certainly more reliable and easier to control. The most common number of courses was fourteen, six on the fingerboard with eight diapasons. The diapasons were tuned diatonically according to key. Some early examples have only twelve courses, while Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger used a fully chromatic nineteen-course instrument, an example of which may be found in a private collection in Mantua. Many modern players place seven or eight courses on the fingerboard—as was done in France—in order to access the low ![]() and

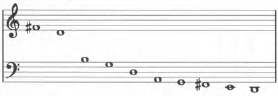

and ![]() so crucial for continuo playing. Surviving instruments and iconographic evidence indicate that some players used double courses over the fingerboard, while others preferred single strings. The latter are more convenient for articulating the long slurred passages—called strascini—so common in solo chitarrone music. Single strings can also be louder, as the player does not have to worry about hitting the double strings against each other. The diapasons were usually single.

so crucial for continuo playing. Surviving instruments and iconographic evidence indicate that some players used double courses over the fingerboard, while others preferred single strings. The latter are more convenient for articulating the long slurred passages—called strascini—so common in solo chitarrone music. Single strings can also be louder, as the player does not have to worry about hitting the double strings against each other. The diapasons were usually single.

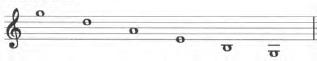

In addition to the strascini mentioned above, theorbists took full advantage of the reentrant tuning of their instrument by playing scale passages across several strings, letting each of the notes ring as long as possible, rather than up and down one or two strings, where each note is stopped as soon as the next one is played. This technique is called campanellas, or “little bells,” and was also employed on the Baroque guitar.7 By playing some passages with campanellas, some with strascini, and some with individually articulated notes, a great deal of variety can be achieved. Because the third string is the highest in pitch, an unusual right-hand fingering pattern was devised—thumb, index, middle, index—in order to play arpeggios in the “correct” sequence from the lowest note to the highest (Example 15.1).8 Not all chords can easily be arpeggiated in the normal sequence without using very complex right-hand fingerings, but the combination of chords in the “right” pitch sequence and those out of order gives the theorbo a special charm.9

Example 15.1. The correct sequence for playing arpeggios.

To the casual observer, theorbos and archlutes look remarkably alike. The main difference is in the length of the fingered strings, which on the theorbo is much longer, thus necessitating the top two strings to be tuned an octave lower. It is important to keep in mind that gut-strung instruments usually sound best when the highest-pitched string is very near its breaking point.10 The length of the stopped strings on surviving theorbos is usually between 84 and 96 cm, while some Roman instruments are even longer. The largest instruments were probably tuned in G. Many of today's players perform on very small theorbos of around 76 cm. which, though easy to play, lack the brightness and sonority of full-sized instruments. Such short theorbos were probably originally tuned a third or fourth higher and used as théorbe pour les pièces (see section on French lutes below). Archlutes, on the other hand, tended to have string lengths of around 67 cm.11

Some observers may have used the terms “archlute” and “theorbo” generically in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but experienced musicians clearly knew the difference, since parts specifying one or the other are usually well-conceived idiomatically. The theorbo has a very full tenor register but lacks a true treble, while the archlute has a bright, clear treble but lacks the fullness of the theorbo. In addition, the basic pitch of the theorbo was usually a step higher than that of the archlute. For that reason, they were often chosen not only for their tonal characteristics, but according to the keys they favored. The tiorbino, a small theorbo tuned an octave higher than the regular theorbo, is mentioned in accounts of some oratorio performances and chamber music, though just how common an instrument it was is not known. While the theorbo was preeminent in the early seventeenth century, the archlute seems to have overtaken its larger cousin by 1700, probably because its shorter string length makes for easier playability in a wider variety of keys. Archlutes are also more agile and seem to have often played florid, obbligato-style accompaniments, as opposed to the more sonorous approach used on the theorbo.

The use of the archlute and theorbo in seventeenth-century Italy may be summarized as follows:

1. Solo works for the theorbo were written by Kapsberger, Piccinini, and Bellerofonte Castaldi, while for the archlute, composers include Kapsberger, Piccinini, Bernardo Gianoncelli, Pietro Paolo Melii, and Giovanni Zamboni.12 Castaldi's 1622 collection includes nine duets for theorbo and tiorbino. One possible reason so little solo archlute music survives from the late seventeenth century is that lutenists made arrangements of violin sonatas (Arcangelo Corelli, Michele Mascitti, etc.) for solo archlute. Sylvius Leopold Weiss is known to have played violin concertos on the lute right off the violin part—a practice he may have become acquainted with in Rome.

2. The theorbo was the favored instrument for accompanying singers and instrumental ensembles in the first half of the century, while the archlute became more popular in the second half of the century, especially in Rome, where ensembles with two or three archlutes are common from the 1640s on.13 Opera orchestras regularly featured two to four theorbos for most of the century, sometimes augmented with or replaced by archlutes.

The French approach to adapting the lute in the seventeenth century was quite different from that of the Italians. At first they, too, added extra bass strings to the standard six-course Renaissance lute, but they were forced to stop at the tenth-course C, the lowest note satisfactorily produced by plain gut strings without increasing the string's length. At this point, according to Marin Mersenne, experiments were undertaken to increase the resonance of the instrument. One player attached organ pipes to the neck of the lute, in the hope they would vibrate sympathetically with the strings of the lute. When that did not prove successful, a musette bellows was attached to the organ pipes, but this proved too cumbersome for the player, having to pump the bellows with his right arm while trying to pluck the strings at the same time.14

Others experimented with different tunings of the open strings in an effort to produce chords involving as many open strings as possible, thereby increasing the resonance of each chord, since gut is most resonant the longer the vibrating string length. In other words, open strings are more sonorous than stopped strings, chords in the first position are more sonorous than those in higher positions, and so on. The result was the adoption of more than a dozen scordatura tunings, many of which were given identifying names: “French flat tuning,” “French sharp tuning,” “ton de la harpe,” “à cordes avalées,” and the soon-to-become-standard French D-minor tuning.15 After experimentation with Jacques Gautier's (aka Gaultier) twelve-course lute with an extended pegbox, the French settled on eleven courses, all on one neck.16

The new French tunings produced more resonance than was possible with the old Renaissance tuning (vieux ton), but they did not increase the volume of sound, nor did the French show any particular interest in doing so. For that reason, the French lute of the second half of the seventeenth century was primarily a solo instrument, sometimes used to accompany solo singers or small groups of instruments. Its intimate quality was expressed by one writer in this way:

This instrument will suffer the company of but fewe hearers, and such as have a delicate ear…It is a disgrace for the lute to play country dances, songs or corants of violins…. To make people dance with the lute it is improper…it is neither proper to sing with the lute.17

Earlier in the century more than a dozen lutes were used to play in court ballets, while the lute was the favorite instrument for accompanying the hundreds of airs de cour published during the first forty years of the century. Taste evidently changed along with the tuning and setup of the lute in the second half of the century.

Jacques Mauduit is said to have introduced the theorbo into France around 1610. It apparently did not become a prominent continuo instrument there until the 1640s but eventually supplanted the lute in that capacity. Ensembles consisting of violins, flutes, theorbo, bass viol, and harpsichord are often mentioned in the 1670s and 1680s.18 The royal opera under Jean-Baptiste Lully normally included several theorbos in the continuo section. The earliest solo French theorbo music is from the 1680s, with the finest repertory being that by Robert de Visée. James Talbot's tuning for a “lesser French Theorbo for Lessons” is a fourth higher than the standard continuo theorbo in A, suggesting solo pieces may have been played on the smaller instrument. This would certainly make some of the music brighter and easier to articulate; however, the key indications in Vaudry de Saizenay's manuscript correspond to A tuning.19 Solos were probably played on both instruments. Whether the lesser French theorbo was also used to play continuo is not known, but it would certainly make sense that different sizes and tunings be employed in ensembles with multiple theorbos. The archlute does not seem to have been very common in France, though Charles (or François) Dieupart calls for it in his Six suittes de clavessin pour un violon ou flute avec une basse de viole ou un archilut (ca. 1705). It was so unfamiliar to Mersenne that he printed the wrong picture of it in his Harmonie universelle (1636) and had to print a correction several hundred pages later in the book!

The use of the lute in seventeenth-century France may be summarized as follows:

1. Solos, duets, quartets, songs, and small ensemble music in Renaissance tuning for ten courses until about 1645; ballet de cour ensembles of up to forty lutes are recorded in various sources.20

2. Solos and duets in the new tunings for nine to eleven courses starting with Francisque in 1600, becoming commonplace by 1630. To my knowledge, the only examples of these tunings being used for continuo are two English sources, Oxford Bodleian Library, MS Mus. Sch. E 410414 and Nanki Ms. N4/42.

3. The theorbo was the workhorse continuo instrument from about 1640 onward. A significant solo repertory for it emerged in the late seventeenth century.

England

In England, both Italian and French tunings and instruments were used. The Renaissance tuning persisted into the eighteenth century, while the French transitional tunings began to make an appearance as early as 1606. The ten-course lute was the standard English lute from 1610 until around 1645, when the double-headed twelve-course lute took over.21 The transitional tunings were popular between 1620 and 1700, while the old tuning persisted on the archlute until late into the eighteenth century. The D-minor “Baroque lute” tuning is also represented in numerous sources, so it would seem all of the tunings were practiced in England during the seventeenth century.

The twelve-course lute in transitional tunings was used for some ensemble music (e.g., Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Mus. Sch. E 410414), but it was the “lusty theorbo” that became the standard English continuo instrument by the 1640s. The theorbo had been introduced into England by Inigo Jones as early as 1605, when his instrument was confiscated by a customs officer at Dover, concerned it may have been “some engine [of war] brought from Popish countries to destroy the King.” The suspicion with which the instrument was regarded by that customs official seems to have remained unchanged over the centuries. Whether this episode slowed the acceptance of the theorbo, or whether the popularity of the lute delayed its ascendance, is hard to determine.

Lynda Sayce has recently made a compelling case that the term “theorbo-lute” referred to a twelve-course, double-headed lute in standard Renaissance tuning until the 1670s, despite the existence of large, reentrant Italian theorbos in England as early as 1605.22 This means that the instrument used to accompany the songs and consorts of William Lawes, Charles Coleman, and John Jenkins was not a large reentrant theorbo, but a Renaissance lute with extra bass strings.23 In the 1670s the instrument was enlarged and the top string tuned down an octave, but the G tuning was maintained, an important point considering the English predilection for fat keys. Italian theorbos probably still existed in England at this time, but their tuning in A would have been awkward for playing in fat keys, while the often high-lying bass parts of Lawes, Matthew Locke, and Henry Purcell would have been unsatisfying with b as the highest string. Talbot describes a large theorbo with double courses throughout and the basses strung in octaves, though whether this was typical of the “English Theorbo” is not known. It is certainly easier to be “lusty” on thick single courses than on double courses, which rattle easily, but this may not have been what English players had in mind. Recent experience has shown that English theorbos suit the music written for them better than do Italian instruments, though this causes a dilemma for today's players, who must decide how many different instruments to buy and how to travel with all of them. To make matters more complicated, some English sources suggest theorbos could also be strung with wire strings.24 Such diversity is frustrating to the modern performer trying to get the “right” instrument for the music. It is typical, however, for a period in which there was no standardization, and individual builders and performers were constantly experimenting to develop the best instrument for the music.

According to Thomas Mace, an organ with “a lusty theorbo” was the preferred continuo team for string consorts. Title pages of songbooks throughout the seventeenth century list the “theorbo lute” as the first choice for accompanying singers until 1687, the earliest instance in which the organ and harpsichord are listed ahead of the theorbo. Whether “theorbo lute” always referred to the English theorbo proper, or whether it sometimes referred to any kind of theorboed lute—including the archlute—is not clear. Some scholars have suggested the archlute was not introduced into England until the arrival of George Frideric Handel and the Italian opera in 1710, but a surviving obbligato accompaniment to Purcell's “How pleasant is this flow'ry plain”25 strongly suggests the archlute. Not only is it written in a seventeenth-century hand, it is also mentioned in Matthew Locke's Melothesia of 1673.

The use of the lute in seventeenth-century England may be summarized as follows:

1. Renaissance tuning on eight- to ten-course instruments until the mid-1640s for solo music, songs, and ensemble music in the English consort style; on twelve-course instruments until the eighteenth century.

2. Transitional tunings used on eight-course lutes as early as 1606, on ten- to twelve-course instruments into the eighteenth century for solo music, songs, and ensemble music in the French style.26 Whether or not continuo playing in these tunings was commonplace, as suggested by the examples in the Nanki Ms. (ca. 1629), is not known at this time.

3. The D-minor tuning first appeared in the 1630s and continued into the eighteenth century. Most of the surviving repertory for it consists of arrangements of popular songs, dances, and division pieces, including the works of Purcell and Handel.

4. The English theorbo in G with the top string down the octave was the preferred continuo instrument for songs and consort music from about 1670 on. The Italian theorbists who played for Handel probably played Italian instruments.

5. The archlute was used as a continuo and obbligato instrument from about 1660 until at least the 1740s.

Germany

Germany and Bohemia also followed Italian and French currents throughout the seventeenth century. The ten-course lute in old tuning remained popular into mid-century both as a solo and as a consort instrument despite the introduction of the new French tunings in the 1630s. The vogue for these tunings lasted into the late seventeenth century in Germany as it had in France, but again the D-minor tuning took over as the most common one by 1650. The chitarrone was introduced into Germany in the 1610s and is frequently mentioned alongside the liuto—either an eight- or ten-course lute or an archlute—as a continuo instrument. It was used in Italianate music, concertos, cantatas, sonatas, operas, and so on well into the eighteenth century. A theorbo part in tablature for Dieterich Buxtehude's Fürchte dich nicht survives in a manuscript in Uppsala along with theorbo parts for several other late seventeenth-century German works (see Example 17.2 in the chapter on Basso Continuo). Another kind of theorbo using the D-minor tuning, sometimes minus the top f', is described by Ernst Gottlieb Baron in 1727.27 Exactly when it came into use or whether its use was widespread is not known. Obbligato parts for the tiorba found in early eighteenth-century Viennese operas seem to have been written with the D-minor tuning in mind, not the old Italian reentrant tuning. However, the painting of Johann Joseph Fux directing Costanza e Fortezza shows him playing an enormous theorbo that was probably tuned in the Italian manner. The eleven-course D-minor lute was widely used as a continuo and solo instrument in German and Bohemian chamber music of the time (Esaias Reussner, Ferdinand Ignaz Hinterleitner, etc.). The archlute was also common in German-speaking countries in the seventeenth century, as can be seen by the numerous obbligato parts in operas and oratorios of the time (Camilla de Rossi, Antonio Draghi, Agostino Steffani). The lute was so popular around 1700 that Balthasar Janowka claimed that one could “cover all of the roofs of Prague with lutes.”28

A plucked instrument of this period which has not yet received much attention is the gallichon, also called colascione, calizon, or calchedon, not to be confused with the southern Italian colascione, a two- or three-stringed folk instrument that played mostly parallel fifths and octaves (e.g., Kapsberger's and Piccinini's parodies called Colascione). A large six-course lute tuned a tone lower than the modern guitar (D G C f a d') or (F G C f a d'), the gallichon was used as a solo and continuo instrument. Parts for it survive in sacred vocal music by Giovanni Felice Sances, Sigre Anton Wilhelm Heinrich Gleitsmann, and Georg Philipp Telemann, while Bach's predecessor in Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau, used it in performances of his church music, without leaving a separate part for it. Presumably, it played from the continuo part together with the organ. Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello left a collection of eighteen very fine solo partitas for it in a manuscript in Dresden.29 Talbot describes a gallichon loaned to him by the Moravian composer Gottfried Finger, measuring “just over two feet long” with a string length of “17 inches.”30 It is unclear precisely when and where the instrument was invented and how widespread its use as a continuo instrument was, but the survival of numerous originals suggests it was not an insignificant instrument.

Another instrument mentioned in many sources but not yet revived in the twentieth century is the angélique, or angel lute. A gut-strung, extended-neck lute, it looks very much like a theorbo but has ten strings on the lower pegbox and six on the upper, tuned diatonically on “white” notes from D to e'. Talbot observed that it is “more proper for slow and grave lessons than for quick and brisk by reason of the continuance of sound when touched which may breed discord.”31 Jakob Kremberg's Musikalische Gemüths-Ergötzung, published in Dresden in 1689, contains charming arias with angélique, lute, and guitar accompaniments in tablature. Thurston Dart has suggested the instrument was invented by the Parisian lutenist Angélique Paulet, but the handful of surviving angéliques are found in museums in Schwerin and Leipzig and were made by German builders.

Spain

In Spain, the word vihuela was still used in the seventeenth century, though it seems to have become synonymous with the guitar in many instances, and therefore no longer in the old Renaissance lute tuning it used in the previous century.32 How common the Renaissance lute tuning remained in seventeenth-century Spain is still unclear. The theorbo was known by at least 1624, when a member of the Piccinini family brought one over from Rome. It is shown in several Spanish paintings of the time and is mentioned in a number of musical sources as well. The archlute is also called for in several works, though the extent of its use is unknown at this time. While theorbo and archlute were used in Spain in the seventeenth century, they were not as popular, typical, or necessary as the harp and the guitar. The latter two instruments shared repertory and were often played together in ensemble. The bright, plucked sound of the Spanish cross-strung harp with the strummed guitar is a delightful combination for the rhythmic, dance-oriented music of the time. The Florentine stage engineer Luigi Baccio del Bianco, who worked on productions of the court plays in Madrid in the 1650s, wrote of performances in which el cuatro, a group of four guitars, accompanied singing and dancing in court theatrical productions.33 The principal continuo player at court was the harpist and composer Juan Hidalgo, and it is clear from the documents that guitars and harps played together as the mainstay of the improvising continuo band. This combination was quite common for Spanish dance music of the time, as well as for accompanying singers.

TECHNIQUE

The period around 1600 was a time of transition and experimentation in lute technique. The Renaissance thumb-under technique, which facilitated rapid articulation by using the whole arm to generate energy, was gradually replaced by the “thumb-out” position, which produced a brighter, more penetrating sound, appropriate for ensemble playing.34 The arm movement of the thumb-under technique may have been considered visually inelegant in the early Baroque as well. In the Renaissance, the standard right-hand fingering was an alternation of the thumb with the index finger to produce the characteristic strong/weak pairing so important to the music of this period. The thumb/index alternation also produces the velocity required by sixteenth-century divisions. The thumb was also responsible for bass notes and would jump from the treble to the bass as needed. This articulation continued into the seventeenth century; however, with the increase in the number of courses at this time, coupled with the more active bass lines of the early Baroque, leaping with the thumb became less practical and was eventually dropped in favor of middle/index alternation. This is generally less agile and fluid than the thumb/index alternation, but it allowed the thumb to remain in the bass register, a necessity when dealing with the ten- to nineteen-course instruments of the seventeenth century. Details about this transition are discussed in Beier, “Right Hand Position,” and O'Dette, “Tone Production.” Another essential technique used in this period involves the rest stroke with the thumb, that is, resting the thumb on the next-highest string after playing each bass note. This is important not only for orientation, but also to provide a more solid sound.

Soloists generally preferred the sound of the lute when played without fingernails, while ensemble lutenists often used long fingernails on their right-hand fingers. Thomas Mace remarked,

Strike not your Strings with your Nails, as some do, who maintain it the Best way of Play, but I do not; and for This Reason; because the Nail cannot draw so sweet a Sound from a Lute, as the nibble end of the Flesh can do. I confess in a Consort, it might do well enough, where the Mellowness (which is the most Excellent satisfaction from a Lute) is lost in the Crowd; but Alone, I could never receive so good Content from the Nail, as from the Flesh: However (This being my Opinion) let Others do, as seems Best to Themselves.35

Sylvius Leopold Weiss maintained that

In chamber music, I assure you that a cantata à voce sola, next to the harpsichord, accompanied by the lute has a much better effect than with the archlute or even the theorbo, since these two latter instruments are ordinarily played with nails and produce in close proximity a coarse, harsh sound.36

This suggests that those who played in large ensembles used nails, while those who played solos or intimate chamber music preferred the sound produced by flesh. Many who played theorbo and archlute also played the guitar, which also appears to have been played with fingernails in many cases. Certainly the strummed rasgueados on the guitar are more exciting when played with fingernails. Obviously, each player must make his/her own decision regarding the nail question and decide when and how to compromise.

Guitar

The guitar played an extremely important role in the seventeenth century both as a solo and continuo instrument. It was an essential instrument in the dance music of the time, often combined with castanets in performances of sarabands and chaconnes. Guitars came in a wide variety of sizes with four or five courses, the latter being standard for most solo repertory. The standard instrument was tuned e' b g d a, with larger instruments tuned a tone lower in d'; smaller instruments in a' and b' were used to add color to consorts. According to Giovanni Paolo Foscarini, ensembles involving multiple guitars should employ instruments of different sizes and tunings to produce a fuller, richer sound. There were numerous ways of tuning the basic five courses with regard to octaves (see “Tuning Charts” below). Finding the right tuning for the music is extremely important if one is to make sense of the voice leading, especially in campanellas passages. Campanellas are scale passages in which each note is played on a different string, allowing the notes to ring over like “little bells.” James Tyler has given a list of the tunings he believes apply to each composer in his book The Early Guitar. Recently, many players have become convinced of the need for a high g' octave string on the third course for Santiago de Murcia and other Spanish composers.37

The two basic techniques employed on the guitar at this time were plucking (punteado) and strumming (rasgueado), often employed in the same pieces. The elaborate strumming techniques discussed in seventeenth-century sources are reminiscent of many Latin and South American folk traditions and provide the essential color and rhythm to much seventeenth-century music.38 The guitar was the preferred instrument for accompanying vocal music in the popular vein (canzonette, villanelle, and villancicos) in Italy, France, Spain, and England, prompting Italian publishers to include chord symbols, known as the alfabeto, above the vocal parts in their prints of this repertory. The alfabeto was a system of notating chords by letters, relieving amateurs of the task of learning to realize unfigured bass lines.

Many chords sound in inversions on the Baroque guitar due to its reentrant tuning, giving the instrument a special charm. Some modern observers have expressed disdain for the guitar's inability to realize bass lines in the notated octave, but this “defect” provides a rustic character that enlivens the music in a way the theoretically “correct” harmonies cannot provide. Another characteristic of the Baroque guitar is the use of extra dissonances to simplify left-hand fingering and to facilitate strumming. If a chord were to require an awkward stretch, or if a regular note of the harmony is not easily reachable, guitarists simply added interesting dissonances (see Example 15.2). This aspect of Baroque guitar practice may have inspired the acciaccature which add so much spice to the keyboard music of Domenico Scarlatti and Antonio Soler.

![]()

Example 15.2. Added dissonance to simplify left-hand fingering.

The guitar was extremely popular throughout Europe in the seventeenth century. Solo and ensemble music survives from Italy, Spain, Portugal, Mexico, England, France, and Germany. For a comprehensive list of sources, see Tyler, “Early Guitar.”

Cittern, Gittern, Orpharion, and Bandora

The cittern was popular from the Renaissance through the seventeenth century, especially in England, France, Holland, and Italy. It was strung with a combination of iron and brass strings arranged in pairs—some of the low courses were even triple-strung with octaves—and plucked with a quill. Most English and French citterns had four courses, while Italian instruments had six. The cittern is a chordal instrument fulfilling much the same role as a rhythm guitar in a rock band. Like the Baroque guitar, the cittern lacks a real bass and produces many chords in inversion. For this reason, it is best used in combination with another instrument that is able to provide the written bass line. The cittern was most commonly used in dance ensembles and to accompany broadside ballads. It is an essential member of the English broken consort, and it survived in Italy as a continuo instrument. The Italians added bass strings to the cittern as they had to the lute, resulting in an instrument they called ceterone or archcittern. Claudio Monteverdi calls for ceteroni in Orfeo, though most modern performances ignore his suggestion. The parts were probably similar to the ones provided by Melii in his Balletto of 1616. English solo music for a fourteen-course archcittern was published by Thomas Robinson in his New Citharen Lessons of 1609.

In his 1666 Musick's Delight on the Cithren, John Playford advised,

For your right hand, rest only your little finger on the belly of your Cithren, and so with your Thumb and first finger and sometimes the second strike your strings, as is used on the Gittar; that old Fashion of playing with a quil is not good, and therefore my advice is to lay it aside; and be sure you keep your Nails short on the right hand.39

He went on to explain that the cittern had fallen out of favor, but he hoped that by adopting “the gittar way of playing” he could “revive and restore this Harmonious Instrument.” This makes clear that the cittern was normally played with a quill, but in an attempt to bring it back into favor in the late seventeenth century, finger plucking was advocated. Besides Playford, there is only one other late source which seems to require the cittern to be played with the fingertips.

“Gittern” was the name given to the Renaissance four-course guitar in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century England, though in the latter era it sometimes referred to a small cittern in guitar tuning, strung with wire strings and played with a quill. This may have been an attempt to enable guitarists to make “sprightly and Cheerful Musick” on wire strings without having to learn a new tuning.40 Music for the gittern was published by Playford in 1652 and survives in a few manuscripts.

The bandora, or pandora as it is called in some sources, was devised “in the fourth year of Queen Elizabeth” (i.e., 1561) by the viol maker John Rose. It is essentially a wire-strung bass lute with a scalloped shape, a slightly vaulted back, and often a slanted bridge and nut to increase the length of the bass strings. The surviving music for bandora includes a small but rewarding solo literature, a number of song accompaniments, and several lute duet grounds;41 it is, however, in the broken consort repertory that the bandora really shines. It is an irreplaceable member of that ensemble, filling a double role as continuo and double bass. Together with the cittern, the bandora provides a continuo with the dynamic flexibility required in such a delicately balanced ensemble. The bandora is mentioned as a continuo instrument on the title page of numerous seventeenth-century collections—including several published in Germany—but it seems to have gradually fallen out of favor after about 1640. There is, however, one fascinating account by Roger North of bandoras strummed with quills accompanying oboes and violins in late seventeenth-century consort music, suggesting that the instrument was played in some circles throughout the century.

The orpharion is a wire-strung instrument with a scalloped outline and a flat or slightly vaulted back, tuned like a lute. (Robert Spencer has suggested the name is a combination of Orpheus and Arion.42) It was played almost exclusively in England and in some parts of Holland and northern Germany. Because of its tuning, and due to the fact that it is mentioned as an alternative to the lute on the title pages of many books of lute songs, the orpharion can be used to play any English lute music. In fact, in thirty-two household inventories made between 1565 and 1648 the bandora and orpharion occur as frequently as the lute. While music published specifically for the orpharion mostly requires a seven-course instrument, the finest surviving example, made by Francis Palmer in 1617, has nine courses. In his New Booke of Tabliture of 1596, William Barley explains that on the orpharion, the fingers must be “easily drawn over the strings, and not suddenly gripped, or sharply stroken as the lute is: for if ye should do so, then the wire strings would clash or jarre together the one against the other…Therefore it is meet that you observe the difference of the stroke.” 43

MANDORE, MANDOLA, AND MANDOLINO

Very small members of the lute family became popular in France, England, Germany, and Italy in the seventeenth century. The mandore was, according to Praetorius,

like a very little lute with four strings tuned thus: g d' g' d”. Some are also strung with five strings or courses and go easily under a cloak. It is used very much in France where some are so practised on them that they play courants, other similar French dances and songs as well as passamezzi, fugues, and fantasias either with a feather quill as on the cittern or they can play with a single finger so rapidly, evenly, and purely as if three or four fingers were used. However, some use two or more fingers according to their own use.44

In 1623 Piccinini observed, “In France they are used to playing a very small instrument of four single strings called the Mandolla, and they play it with the index finger alone. I have heard some players play very well.”45 A quill may have been used for ensemble performances, while the fingers were used for solo playing. Praetorius gives three more tunings, the first of which seems to have been the most common in France: (1) g″ c″ g′ c′; (2) c” g′ c′ g c; and (3) c″ f′ c′ f c.46 Solo music for the first tuning survives in France (Chancy's Tablature de mandore) and in several Scottish manuscripts.47

In Italy the instrument was called the mandora, or later mandolino, and used the tuning g″ d″ a′ e′. By 1657 a fifth and sixth course had been added, providing a, b, and g below the e' string. Surviving four-, five-, and six-course instruments are mostly double-strung except for the first course, which, as on the lute, was often single. A substantial repertory of solo and ensemble music survives for this instrument, a detailed list of which can be found in Tyler and Sparks, Early Mandolin.48 The modern, four-course, metal-strung mandolin with violin tuning was invented in Naples in the mid-eighteenth century and had its own independent repertory.

NOTES

1. Nurse, “Development”: 102–107.

2. See picture in Kinsky, “Piccinini”: 103–118.

3. Spencer, “Chitarrone”: 408–411; Mason, Chitarrone: 3–7.

4. Mason, Chitarrone: 1–10, 15–16.

5. North, Continuo: 63–65.

6. Mason, Chitarrone: 10–14.

7. See North, Continuo: 168.

8. See North, Continuo: 164–167.

9. Ibid.: 164–165.

10. Nurse, “Development”: 102–107.

11. See Spencer, “Chitarrone”: 416.

12. See North, Continuo Playing: 160, 294–296; and Mason, Chitarrone: 84–88.

13. See Maugars, Response: 9 of trans.

14. See Bailes, “Introduction,” for more details.

15. See ibid. and accompanying examples.

16. Lowe, “Historical Development”; Bailes, “Introduction”: 218.

17. Mary Burwell's Lute Book, ca. 1670 (based on the teaching of Jacques Gautier), preface.

18. See Julie Anne Sadie, Bass Viol: 24–5, 33, 41, 66.

19. James Talbot, Oxford, Christ Church Mus MS 1187; Besançon, Bilbliothèque de la Ville, Vaudry de Saizeney MS 279152.

20. See Anthony, French Baroque: illustrations 2 and 4.

21. Spring, Lute in England; Lowe, “Historical Development”: 11–25.

22. Sayce, “Continuo Lutes”: 667ff.

23. Henry Lawes's theorbo, which had survived intact in Oxford, was burned in a bonfire of “unnecessary artifacts” in the nineteenth century.

24. Mason, Chitarrone: 10–14.

25. Spink, “English Song”: 216; Holman, “Continuo”; recorded on Hark, How the Wild Musicians Sing: Symphony Songs of Henry Purcell, Redbird/The Parley of Instruments, Hyperion CDA 66750.

26. Lowe, “Historical Development.”

27. Spencer, “Chitarrone”: 414, 419.

28. Janowka, Clavis.

29. Modern eds. of nos. 6, 7, and 16 by Ruggero Chiesa (Milan: Edizioni Suvine Zerboni, 1976–77).

30. Prynne, “Talbot's Manuscript”: 52ff.

31. Talbot, Ms. 1187; see Baines, “Talbot's Manuscript.”

32. See O'Dette, “Plucked Instruments”: 147.

33. Stein, Songs: 149.

34. Beier, “Right Hand Position”: 5–24.

35. Mace, “Musick's Monument”: 73.

36. Cited in Douglas Alton Smith, “Baron and Weiss”: 61.

37. See Lorimer, Saldivar Codex: xix.

38. Weidlich, “Battuto”: 63–86; Tyler, Early Guitar: 77–86.

39. Playford, Cithren: preface.

40. See Ward, “Sprightly.”

41. Spencer, “Chitarrone.”

42. See Norstrom, Bandora.

43. Barley, Tabliture: preface.

44. Praetorius, Syntagma II: 53; Praetorius/Crookes, Syntagma II: 59; trans. in Tyler/Sparks, Early Mandolin: 8.

45. Piccinini, Intavolatura: preface.

46. Praetorius, Syntagma II: 28; Praetorius/Crookes, Syntagma II: 41.

47. See McFarlane recording, cited in the discography at the end of this chapter.

48. Tyler/Sparks, Early Mandolin: appendix III.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailes, “French Lute Music”; Beier, “Right Hand Position”; Bocquet, Approche; Kinsky, “Piccinini”; Lawrence-King, “‘Perfect’ Instruments”; Lorimer, Saldívar Codex; Lowe, “Historical Development”; Lowe, “Renaissance and Baroque”; Lundgren, New Method; Mace, Musick ‘ s Monument; Mason, Chitarrone; Maugars, Response; Ness, “Lute Sources”; Nordstrom, Bandora; North, Continuo Playing; Nurse, “Development”; O'Brien /O'Dette, Lute Made Easie; O'Dette, “Observations”; O'Dette, “Plucked Instruments”; Poulton, Lute Playing; Poulton, Tutor; Radke, “Beiträge”; Russell, Santiago; New Grove Instruments; Satoh, Method; D. A. Smith, “Baron and Weiss”; Spencer, “Chitarrone”; Spring, Lute in England; Stein, Songs; Tyler, Brief Tutor; Tyler, Early Guitar; Tyler, “Mandore”; Tyler, “Italian Mandolin”; Tyler/Sparks, Early Mandolin; Ward, “Sprightly”; Weidlich, “Battuto.

DISCOGRAPHY

Alessandro Piccinini: Intavolature di liuto et chitarrone, libro primo. Nigel North, lute. Arcana A6.

Ancient Airs and Dances. Paul O'Dette, lute, archlute, and Baroque guitar. Hyperion CDA66228.

The Complete Lute Music of John Dowland. Paul O'Dette, lute. Harmonia Mundi HMU 9071604 (5 vols.).

Henry Lawes: Go Lovely Rose Songs of an English Cavalier. Nigel Rogers, tenor; Paul O'Dette, lute, theorbo, and guitar. Virgin Classics VC 5 45004 2.

Denis Gaultier: La rhetorique des dieux. Hopkinson Smith, lute. Astrée AS 6.

Henry Purcell: Complete Ayres for the Theatre. The Parley of Instruments, directed by Roy Goodman. Hyperion CDA67001/3.

Henry Purcell: Hark, How the Wild Musicians Sing. Redbird/The Parley of Instruments. Hyperion CDA 66750.

Il Tedesco della Tiorba: Kapsberger Pieces for Lute. Paul O'Dette, lute and chitarrrone. Harmonia Mundi HMU 907020.

John Jenkins: Late Consort Music. The Parley of Instruments. Hyperion CDA 66604.

The King's Delight. The King's Noyse. Harmonia Mundi CD HMU 907101.

Lord Herbert of Cherbury's Lutebook. Paul O'Dette, lute. Harmonia Mundi HMU 907068.

Luz y Norte (Released in the United States as Spanish Dances). The Harp Consort, Andrew Lawrence-King, director. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi.

Matthew Locke: The Broken Consort—Part 1. The Parley of Instruments. Hyperion CDA66727.

Pièces de luth: French Lute Music of the Seventeenth Century. Nigel North, lute. University of East Anglia.

Pièces de luth. Anthony Bailes, lute. EMI 1C 063 30938.

The Queen's Delight. The King's Noyse. Harmonia Mundi CD HMU 907180.

The Scottish Lute. Ronn McFarlane, lute. Dorian DOR 90129.

Sigismondo D'India: Lamento d'Orfeo. Nigel Rogers, tenor; Paul O'Dette, lute and chitarrrone; Andrew Lawrence-King, harp, harpsichord and organ. Virgin Classics VC 7 907392.

William Lawes: The Royal Consorts. The Purcell Quartet with Paul O'Dette and Nigel North, theorbos. Chandos CHAN 0584/5.

TUNING CHART

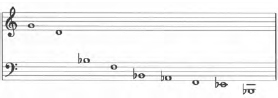

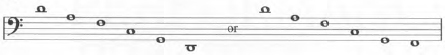

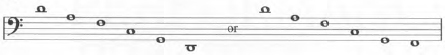

Example 15.3a. Fourteen-course archlute.

![]()

Example 15.3b. Fourteen-course theorbo.

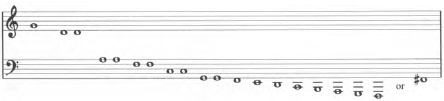

Example 15.3c. Ten-course lute in Renaissance tuning (vieux ton).

Example 15.3d. Eleven-course lute in D minor tuning.

Example 15.3e. À cordes avalées.

Example 15.3f. French flat tuning.

Example 15.3g. French sharp tuning.

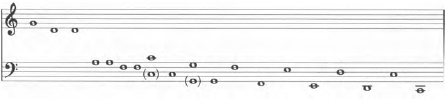

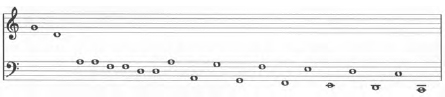

Example 15.3h. Gallichon.

Example 15.3i. Angélique.

Example 15.3j. Baroque guitar tunings.

Example 15.3k. Mandore.

Example 15.3l. Mandolino.