![]()

Ornamentation in

Early Seventeenth-Century Italian Music

The seventeenth century was a period of Italian dominance in musical matters over much of Europe. Italian singers and instrumentalists were in great demand in Germany, Austria, Eastern Europe, and in England, and they brought with them their styles of ornamented singing and playing. A discussion of Italian ornamentation practice in the seventeenth century thus is relevant to the performance of much of the music produced outside of Italy as well. In addition, seventeenth-century ornamentation practice is a blending of traditional practices bequeathed from the sixteenth century and innovative techniques developed in connection with the new monodic singing style fashionable after the turn of the century.

The revolution in musical style around 1600 that led to the birth of monody and opera was as much a radical change in the art of singing as it was in the art of composition. One of the pioneers of the new style, Giulio Caccini, was first and foremost a virtuoso singer; he committed his “new way of singing” to paper only to prevent other singers from spoiling his songs by their “improper way of singing them.” The new style of singing involved principally three aspects: (1) greater attention to the sentiments of the text, (2) a particular kind of rhythmic freedom (known as sprezzatura) which gave precedence to natural speech rhythms and created a kind of “speech in song” (recitar cantando), and (3) the use of a whole range of ornamental devices which were either new or used in new ways. We can get a sense of the novelty of these devices by listening to a description of contemporary singers by the Roman nobleman Pietro della Valle, himself present in 1600 at the first performance of Emilio de’ Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di anima, e di corpo:

However, all of these [singers of the old school], beyond the trilli, passaggi and a good putting forth of the voice, had in singing nearly no other art, such as the piano and forte, gradually increasing the voice, diminishing it with grace, expressing the affetti, supporting with judgement the words and their sense, cheering the voice or saddening it, making it merciful or bold when necessary, and other similar gallantries which nowadays are done by singers excellently well. At that time no one spoke about it, nor at least in Rome was news of it ever heard, until Sig. Emilio de’ Cavalieri in his last years brought it to us from the good school of Florence, giving a good example of it before anyone else in a small representation at the Oratorio della Chiesa Nuova, at which I, quite young, was present.1

Perhaps della Valle exaggerates, yet he makes a distinction which seems valid: divisions belong essentially to the old style of singing, affective devices to the new. To be sure, divisions continued to be used (and sometimes written into the music) to a varying degree throughout the first half of the seventeenth century. Even Caccini, who protests so vehemently against the misuse of passaggi, includes many in his own pieces. We will see, however, that many of these passaggi consist of a succession of smaller, more or less formalized ornaments.

Any singer or instrumentalist who sets out to perform seventeenth-century music with stylistic awareness must understand the function of ornamentation. Too often, ornaments are treated as optional extras: small notes to be added to the music at will but with no intrinsic expressive connection to the written notes. To the seventeenth-century musician, however, ornaments were seen in a very different light. Their use was obligatory because they represented an essential means of expressing the sentiments of the text and of displaying grace.

The Renaissance concept of “grace” is fundamental to an understanding of the function of vocal ornamentation in the seventeenth century. Lodovico Zacconi, theorist and singing teacher, takes pains in his Prattica di musica (1592) to demonstrate the relationship between ornamentation and “grace”:

In all human actions, of whatever sort they may be or by whomever they may be executed, grace and aptitude are needed. By grace I do not mean that sort of privilege which is granted to certain subjects under kings and emperors, but rather that grace possessed by men who, in performing an action, show that they do it effortlessly, supplementing agility with beauty and charm.

In this one realizes how different it is to see on horseback a cavalier, a captain, a farmer, or a porter; and one notes with what poise the expert and skillful standard-bearer holds, unfurls, and moves his banner, while upon seeing it in the hands of a cobbler it is clear that he not only does not know how to unfold and move it, but not even how to hold it […]

It is not, therefore, irrelevant that a singer, finding himself from time to time among different people and performing a public action, should show them how it is done with grace; for it is not enough to be correct and moderate in all those actions which might distort one's appearance, but rather one must seek to accompany one's acts and actions with beauty and charm. Now, the singer accompanies the actions with grace when, while singing, in addition to the things stated at length in the preceding chapter, he accompanies the voice with delightful accenti.2

Thus ornamentation is essential to the singer in demonstrating the same “grace” that distinguishes the horsemanship of a cavalier from that of a farmer. It is his means of showing how that which he does, he does not do just properly, but with supreme ease. It is part of the subtle and complicated courtly art of sprezzatura: using complicated artifice to make what is difficult appear to be so easy that it is done without thinking (while not, at the same time, letting it be seen that one is thinking about not thinking).3 Tasteful singing was conceivable without divisions (in fact, it was sometimes preferable), but never without ornaments.

THE DIVISION STYLE

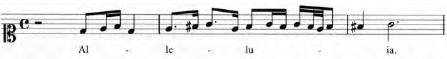

The process of diminution consists of “dividing” the long notes of an unornamented melodic line into many smaller ones. Though denigrated by some of the proponents of the “new style,” divisions were still very much a part of vocal and instrumental practice after 1600. Indeed, the period from 1590 to 1630 was one of the most fertile for the production of division manuals. These manuals typically presented a series of intervals (ascending second, ascending third, etc.) with sample divisions followed by ornamented cadences and often by entire madrigals, chansons, and motets in which the soprano, sometimes the bass, and occasionally all of the parts were provided with elaborate divisions, usually known as passaggi or gorgie. One of the most appealing and useful of the manuals, by Giovanni Luca Conforto, even claims to be a method for learning in a month's time the art of division.4 Figure 16.1 shows the first page of Conforto's manual with divisions on the ascending second.

Figure 16.1. Giovanni Luca Conforto: Breve et facile maniera (1593).

Not all singers, to be sure, were capable of singing passaggi, and this inability could have been the result either of a lack of understanding of harmony and counterpoint or a lack of natural agility of the voice (known as dispositione). There was general agreement that dispositione was a gift from God and that little could be done to develop it in a singer who lacked it. Such singers could still merit praise, however, provided they were “content to sing the part as it stands, with polish, gracefully adding a few accenti,5 for this will be sufficient and will be a pleasure to hear.”6 In an attempt to make his music useful to the largest possible number of singers, Bartolomeo Barbarino presents a series of sacred monodies with unornamented and ornamented versions appearing side by side.7 In that way, the author claims, they will be useful to: (1) singers who have no dispositione, for they can be content to sing the plain versions, (2) singers who have dispositione but no knowledge of counterpoint, for they can sing the divisions as written out, and (3) singers who have both dispositione and a knowledge of counterpoint, for they can sing from the unornamented versions, improvising their own divisions.

Of the division manuals published after 1590, two are of particular interest because they provide a series of ground rules for the construction and employment of divisions. One of them (an undated manuscript called Il dolcimelo, produced about 1590 under the pseudonym Aurelio Virgiliano) gives rules for building divisions, and another—the Prattica di musica (1592) of Lodovico Zacconi—provides guidelines for the improvisation of passaggi in ensemble singing.

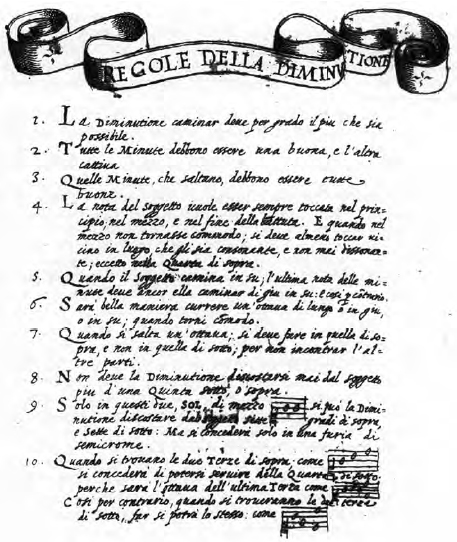

Virgiliano's rules for making divisions, shown in facsimile in Figure 16.2, are the most complete ones provided in any source and are a good point of departure for anyone wanting to learn the art of improvising passaggi. They may be paraphrased as follows:

1. The diminutions should move by step as much as possible.

2. The notes of the division will be alternately good and bad notes.8

3. All the division notes which leap must be good (i.e., consonant).

4. The original note must be sounded at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end of the measure,9 and if it is not convenient to return to the original note in the middle, then at least a consonance and never a dissonance (except for the upper fourth) must be sounded.

5. When the subject goes up, the last note of the division must also go up; the contrary is also true.

6. It makes a nice effect to run to the octave either above or below, when it is convenient.

7. When you leap an octave, it must be upward and not downward, in order not to clash with the other voices.

8. The division must never move away from the subject by more than a fifth below or above.

9. Only on the two Gs in the middle [g′] may the division move away from the subject seven degrees above and seven below, but this is conceded only in a fury of sixteenth notes.10

10. When you find two thirds going upward (g′-b′-d′), you may use the fourth below [the first note], because it will be the octave of the final note. The same is true of descending thirds.

Figure 16.2. Aurelio Virgiliano: Il dolcimelo (ca. 1590).

Virgiliano's rules describe quite accurately the division practice as it appears in written-out examples between 1580 and 1620. To be sure, stepwise motion is more consistently observed in vocal divisions than in instrumental ones. Yet even in instrumental divisions where triadic figuration is more frequently employed, the predominant melodic movement is stepwise.

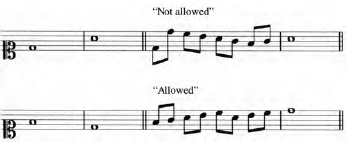

Virgiliano's fourth rule lays down the cardinal principle of divisions, which serves to maintain contrapuntal integrity and proper voice leading. The original note must be sounded at the beginning of the division, exactly in the middle and again just before moving to the next note (with the possible substitution of another consonance in the middle). Example 16.1 shows one of Virgiliano's divisions on the descending second which follows his fourth rule strictly, and one which substitutes the upper third in the middle.

![]()

Example 16.1. Aurelio Virgiliano: Il dolcimelo (ca. 1590).

This rule gives a two-part structure to the division: a formula for departing from and returning to the same note, and a formula for moving to the next note. Awareness of this bipartite structure can be extremely helpful to the beginning improviser, since it aids both in remembering division formulas and in constructing them. A few basic beginning figures can be combined with ending formulas for each of the different intervals to create a virtual infinity of complete divisions.

An examination of Virgiliano's examples reveals the fifth rule to be a corollary to the fourth. If the model moves by an interval larger than the second, the interval may be filled in with division notes, but they must approach the next note of the model from the same direction as the original interval, as shown in Example 16.2.

![]()

Example 16.2. Aurelio Virgiliano: Il dolcimelo (ca. 1590).

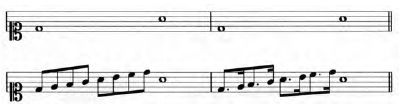

Upon casual reading, Virgiliano's sixth rule may seem to be contradicted by the eighth. Once again, a careful examination of the musical examples provides an explanation. In the sixth rule, Virgiliano allows octave substitutions for the notes of the model. In the course of a division, however, one should not stray from the note one is ornamenting by more than a fifth (see Example 16.3). Exceptions to this rule are in fact rare, though they do occur, in the examples of Virgiliano.

By studying rules such as these, and by playing examples of divisions on intervals, melodic patterns, and cadences, instrumentalists and singers became remarkably proficient at ornamenting single lines. Such divisions were cultivated both as a solo practice, with the other parts normally played on a lute or keyboard, and as an ensemble practice, with all the singers or instrumentalists tossing ornaments back and forth in a virtuoso exchange. The latter practice was clearly open to abuse and consequently was regularly condemned by theorists—so often, in fact, that we can be sure of its popularity among musicians. For practical advice on ensemble ornamentation we can find no better teacher than Lodovico Zacconi. From his treatise we can extract the following advice on employing the gorgie in ensemble singing:

Example 16.3. Aurelio Virgiliano: Il dolcimelo (ca. 1590).

1. In beginning a contrapuntal piece, when the other voices are silent, do not begin with gorgie until the other voices have entered.

2. Spread the divisions in a balanced way throughout the piece. At the end of a piece, do not let loose with an enormous ornament after having left the middle bare and dry.

3. The longer the note the more suitable it will be for divisions. Do not make passaggi on quarter notes, especially if they have text. If they are melismatic, they may have a few divisions. On half notes, some passaggi may be sung as long as they do not obscure the text. On semibreves and breves, one may make as many ornaments as one wishes.

4. Passaggi may be used in all the voices, though bass divisions will require special caution. Zacconi provides a series of special divisions for bass parts, the most noteworthy characteristic of which is the avoidance of filling in the descending fifth movement at cadences. Bass divisions were generally regarded differently from divisions in the other parts, and indeed, some theorists prohibited them altogether. Singers tended to be more indulgent, though even they had some reservations: “It would please me greatly if whoever sings the bass would sing it firmly, sweetly, with affetto and with a few accenti, but of divisions, to tell the truth, I would want very few, and never at the cadences, because the bass is properly the basis and foundation of all the parts. Therefore, he must always be firm, without ever wavering.”11

5. Passaggi may be sung on all the vowels, though some will require special practice.12

Finally, Zacconi is eloquent on the nature of divisions as formulas in which repetition plays an essential part:

The art of the gorgie does not so much consist in variation or in the diversity of the passaggi as it does in a just and measured quantity of figures, the great speed of which does not permit one to perceive whether that which one hears has already been said and is being repeated. On the contrary, a small number of figures can be reused many times in the manner of a circle or a crown, because the listener hears with great delight the sweet and rapid movement of the voice and does not perceive the multiple repetitions through the very sweetness and rapidity of the movements. It is incomparably better to do one thing often and well than, doing many things, to do them poorly in many ways.13

Here Zacconi is particularly perceptive, since one of the most common errors of beginning improvisers is that of trying to be too creative with each ornament. The repetition of formulas, as Zacconi points out, is fundamental to a fluid division style.

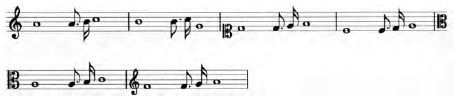

The division practice described by Virgiliano and Zacconi is that which had been in use for the last half of the sixteenth century. It is best exemplified by the manuals of Giovanni Bassano, Girolamo Dalla Casa, and Giovanni Luca Conforto. The divisions tend to flow smoothly with little rhythmic variety and extensive use of sequences. Around 1600, this division practice quickly began to be modified. Rhythms became more varied through the application of radoppiate (sudden bursts of notes in “redoubled” speed) and dotting, rendering the divisions less predictable and less sequential.

According to the sensibilities of the new singing style around 1600, melismatic eighth-note figures (and occasionally sixteenths, as well) were lacking in grace if sung in a rhythmically literal way. As Caccini, Antonio Brunelli, Giovanni Domenico Puliaschi, and others point out, they could be made more graceful by the use of dotting, back-dotting (the so-called Lombard rhythm or Scotch snap), and combinations of both of these. In Caccini's example, shown in Example 16.4, the rhythmic variants labeled “2” are all considered to have more grace than those labeled “1.”

Example 16.4. Giulio Caccini: Le nuove musiche (1602).

Brunelli, who borrows some of Caccini's examples in the preface to his Varii esercitii (1614), claims that all eighth notes, in contrast to sixteenth notes, must be dotted. His examples show a much more rigid dotting scheme in which normal dotting is considered better than no dotting, but back-dotting is “best” (see Example 16.5).

Example 16.5. Antonio Brunelli: Varii esercitii… (1614).

The way in which Brunelli applied these dottings in practice is unclear, since his divisions are all written in undotted eighth and sixteenth notes. If he intended for entire passages to be played with one type of dotting, then his point of view is exceptionally rigid. It was the diversity and contrast of rhythms which seemed to interest the proponents of the new style. Giovanni Bovicelli makes just this point in his Regole, passagii di musica…, 1594:

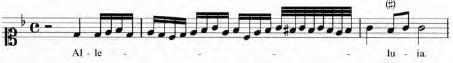

In order to avoid, as the saying goes, always repeating the same old song, often to the great tedium of the listener, [one may make use of] what seems to be an excellent ornamental device, that is, the varying of passaggi frequently, using indeed the same notes, but breaking them up differently. Because just as in writing or in speaking, it is extremely tedious for the listener or the reader if the discourse drags along without any colorful figures of speech, so also the passaggi in singing, if not made in different ways, almost as though brought to life with colors, will bring annoyance instead of delight. I mean to say that the passaggi must sometimes be a series of notes of the same value, and at other times the same notes must be varied in other guises, in such a way that even if the notes are the same, they will appear different, nonetheless, due to the different way they are put forth. [See Example 16.6.]14

Example 16.6. Giovanni Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi di musica (1594).

The frequent varying of rhythms from one bar to the next, or even from one beat to the next, combined with an increasing concern with intelligibility and expression of the text, led to a profound change in the nature of ornamentation practice. The “tickling of the ear” created by “the sweet and rapid movement of the voice” was no longer sufficient for a time in which singing was to be “speech in song,” expressing all the passions of the soul. One still finds divisions in compositions in the new style, but most often these “divisions” can be seen as a succession of individual ornaments, altogether more expressive and varied than the passaggi of the old style.

THE DEVICES (MANIERE)

The specific ornamental devices that were a part of the seventeenth-century Italian singing style can be divided into three categories: melodic devices, dynamic effects, and ornaments of fluctuation. By “melodic devices” we mean those ornaments that actually modify the melodic shape of the original by adding notes to it. In this they are similar to divisions, but briefer and more formulaic. Dynamic effects comprise a series of devices that involve the willful and expressive manipulation of the intensity of a note or a small group of notes. Into the category of “ornaments of fluctuation” we place those ornaments that consists of a regular and periodic fluctuation of pitch, intensity, or both.

MELODIC DEVICES

The Groppo

Among the most frequent of all ornaments were the various kinds of cadential figures known as groppi (groppo is an old form of the modern Italian gruppo = “group”). The groppo is really a type of cadential division that became so common at the end of the sixteenth century that it took on a life of its own: it became an ornamental formula. In its basic form, as in Example 16.7, the groppo involves a repeated alternation between the leading tone and the tonic in which the final movement to the tonic is accomplished by means of a descent to the third below.

![]()

Example 16.7. Basic form of the groppo.

In practice, the groppo was frequently performed radoppiato (redoubled) in sixteenth or even thirty-second notes, with many more repetitions of the half-tone step. Zacconi says that many singers like to fill an entire measure with sixteenth notes in this way, a practice to which he has no objection as long as the rising third figure at the end is done with grace and without violence.

Bovicelli is also concerned with the gracefulness required of singers in terminating the groppo, particularly with regard to placing the final syllable of the text at the end of the ornament:

Where the passaggi are of many notes, and especially in finishing the groppetti, which always end with sixteenth or thirty-second notes, one must, as much as one can, avoid pronouncing a new syllable on that note which immediately follows the groppetto; rather he must go on, slowing down with notes of a bit more value.15

Actually, as can be seen from his musical example in Example 16.8, Bovicelli's solution involves finishing the groppo without changing syllables, then adding (after the final note of the cadence) an additional leading-tone movement in quarter notes (in this case ornamented with two eighth notes) upon which the syllable change is effected. This solution, which he adopts many times in his complete sets of divisions on motets and madrigals, creates a rather strange effect, not without an exotic appeal, but which appears to be uniquely his own.

Example 16.8. Giovanni Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi di musica (1594).

The groppo is sometimes found with more elaborate terminations. Bovicelli gives a formula (Example 16.9), called the groppo rafrenato in which the sixteenth notes of the groppo are “braked” (rafrenato) before the final note.

Example 16.9. Giovanni Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi di musica (1594).

Another elaborate termination is given by Zacconi (Example 16.10), who refers to it as a “double accento.”

![]()

Example 16.10. Lodovico Zacconi: Prattica di musica (1592).

While the groppo normally alternates the leading tone with the tonic, another version is sometimes encountered for use in the descending cadence. Conforto gives the version seen in Example 16.11, calling it the groppo di sotto.

![]()

Example 16.11. Giovanni Luca Conforto: Breve et facile maniera (1593).

A number of writers also describe groppi that incorporate tremoli or trilli. These will be discussed below, together with other ornaments of fluctuation.

The intonatio is an ornament done on the first note of a piece, or of any phrase, and consists of attacking the note a third (or sometimes a fourth) below and then rising to the written note with a dotted figure, as shown in Example 16.12, taken from an example by Bovicelli:

Example 16.12. Giovanni Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi di musica (1594).

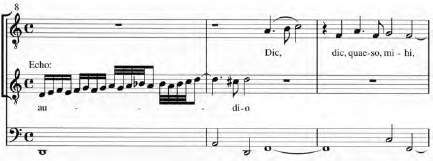

The intonatio seems to have been done with great frequency. Caccini says quite simply that there are two ways of beginning a note: on the written note with a crescendo, or on the third below. His pieces, as well as those of many others, including Monteverdi, have frequent written-out intonatii. In the excerpt of Audi cœlum from Clauido Monteverdi's 1610 Vespers in Example 16.13, the tenor intones the word Dic with a clear intonatio.

Example 16.13. Claudio Monteverdi: Audi cœlum from 1610 Vespers.

The Accento

Probably the singer's most important ornament in the first half of the seventeenth century was the accento. For Zacconi, it was the ornament that most aptly demonstrated courtly grace. For Orazio Scaletta, it was synonymous with “singing elegantly” and was especially useful to the singer not gifted with dispositione (the agility of the throat required in quick divisions).16

Accenti were generally done in places where divisions were considered inappropriate. These include the following:

• moments of strong affect, particularly involving expression of sadness, grief, or pain (thus Zacconi points out that certain kinds of texts particularly require accenti, as, for example, Dolorum meum, misericordia mea, and affanni e morte)

• the beginnings of imitative pieces where one part sings alone

On the other hand, accenti were particularly to be avoided, according to Zacconi:

• in some sorts of fugal entries and fantasies in order not to destroy the imitation

• with declamatory or imperative texts such as Intonuit de celo Dominus, Clamavit, Fuor fuori Cavalieri uscite, and Al arme al arme

The actual form of the accento is somewhat elusive. This is true in part because the use of the term varies in its specificity: at times it seems to refer to a single ornament with an exact melodic and rhythmic shape, while at other times it appears to be a generic term for any ornament of few notes applied to a single melodic interval. Even when used in this generic sense, though, certain common identifiable characteristics recur.

The clearest (and one of the earliest) descriptions of the accento is that of Zacconi, who says the composer is concerned only with placing the musical figures in accordance with the rules of harmony, but the singer has the obligation of “accompanying them with the voice and making them resound according to the nature and the properties of the words.” In particular, he continues, when one has intervals larger than the second to sing, one should make use of some “beautiful accenti.” Zacconi illustrates the accento as applied to ascending and descending thirds with the examples in Example 16.14:17

Example 16.14. Lodovico Zacconi: Prattica di musica (1592).

This written example, however, only approximates the considerably more subtle art of singing the accento,18 as Zacconi's description makes clear. In order to make an accento on the ascending third, for example, the singer must hold the first whole note a little into the value of the second. This lingering, however, must not exceed the value of a quarter note. One must then ascend to the second whole note, but, in passing, make heard “something like a sixteenth note.” Thus, if we insist on fixing in objective rhythmic notation something which Zacconi clearly intends to be rhythmically vague and subjective, an accento on the ascending third would have the form illustrated in Example 16.15:

Example 16.15. Lodovico Zacconi: Prattica di musica (1592).

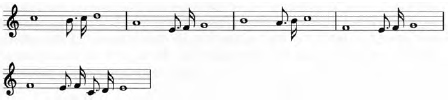

Zacconi's example for the falling third in Example 16.14 introduces another common accento characteristic to be found in many later sources: the use of a rising second to ornament descending intervals. Indeed, accenti on ascending and descending intervals were often looked upon quite differently and had sometimes very dissimilar forms. In its most usual occurrence, the rising second is used to ornament the descending second. This sort of descending accento is called the “true accento” by Francesco Rognoni Taeggio in his Selva de varii passaggi…(1620), who claims that there is another one used in ascending which can sometimes be pleasing, as well.19 His ascending and descending accenti are illustrated in Example 16.16:

![]()

Example 16.16. Francesco Rognoni: Selva de varii passaggi (1620).

For the ascending and descending second (see Example 16.17), Zacconi's accento retains the approach to the second note from the third below. This approach, always using a dotted rhythm, is clearly related to the intonatio. In fact, Zacconi's accento on the second is essentially an intonatio used between two neighboring notes.

Example 16.17. Lodovico Zacconi: Prattica di musica (1592).

In view of the explicit function of the accento of helping to “carry the voice” (portar la voce) from one note to the next on larger intervals, it is rather more difficult to understand many of Zacconi's accenti for ascending fourths and fifths. Here he retains the dotted rhythm, but instead of filling in the interval melodically, as we might expect, in all but two of his examples he retains the leap as seen in Example 16.18:

Example 16.18. Lodovico Zacconi: Prattica di musica (1592).

To understand this rather odd form of accento, we must bear in mind that the purpose of the accento is to help the singer accompany not only the notes, but also the words, with grace. By adopting this form of the accento for a leap of an ascending fourth where there is a change of syllable on the second note, the singer avoids changing syllables on the leap. Instead, he changes syllable on the same note, but slightly after the beat (thus aiding the listener in hearing the consonant) and then produces the melodic interval melismatically.

The accento is described or at least mentioned in a great number of other seventeenth-century Italian sources on singing. Indeed, it is a rare discussion of singing in this period that does not at least mention it. There is, however, some disagreement among these authors whether accenti are properly made on ascending or descending intervals, or on both. While Rognoni claims, as we have seen, that the “true accento” is made only in descending intervals, Scaletta maintains that they may be made only on ascending ones and indeed goes on to say that in a series of ascending intervals, “they are only done when the part ascends to the highest note…if there were four notes ascending by step, the accento would be done on the last and not on the others.”20

The Ribattuta di Gola

Caccini gives the name ribattuta di gola (lit., beating of the throat) to the ornament in Example 16.19. Although the name seems not to have been in general use—indeed, the same ornament appears in the table of ornaments supplied by the editor to the first edition of Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di anima, e di corpo carrying the name Zimbelo—the ornament is encountered frequently in monodies and ornamented pieces of the early seventeenth century.

![]()

Example 16.19. Emilio de’ Cavalieri: “Zimbelo” as found in Rappresentatione di anima, e di corpo.

A striking occurrence of the ribattuta di gola is seen in the setting of Duo seraphim from Monteverdi's 1610 Vespers (Example 16.20), where it is combined with a trillo in a series of virtuoso exchanges.

![]()

Example 16.20. Claudio Monteverdi: “ribattuta di gola” as found in Duo seraphim from 1610 Vespers.

Without question, dynamics have always been a part of musical expression, at least in singing. Sylvestro Ganassi writes in 1535 that just as the painter imitates the effects of nature with different colors, so the singer varies his sound with more or less force according to that which he wishes to express.21 The use of the natural dynamics of the human voice in expressing the text was not new in 1600. What was new was an intentional and self-conscious use of dynamics to create effects and the codification of these effects into ornamental devices. While we do not normally consider dynamics to be ornaments, the seventeenth-century concept of ornamentation went beyond our idea of embellishments to embrace any deliberately employed expressive device.

Beginning around 1600, one occasionally finds dynamics indicated in the music by the use of such terms as piano, forte, and ecco. Usually these words are associated with echo effects. The seicento was interested nearly to the point of obsession in the echo as a natural phenomenon. Natural science was concerned with the physical properties of echoes (an investigation not without interest to the practicing musician, who was urged to seek out a grotto or valley with a clear echo to use as a practice place). The echo fashion filtered into literature in the form of wordplay in which an echo repeats incompletely the final word of a phrase, thus changing its meaning in unexpected and dramatic ways (e.g., clamore…amore…more…re…e). Poems based on wordplay echoes were obvious candidates for a musical setting and helped to increase the popularity of echo effects in both vocal and instrumental music as well.

Occasionally, piano and forte appear as indications to the continuo player, who was instructed to play loudly (with fuller registration) in tutti or ripieno sections, and more softly in concerted solo sections. Paradoxically, this situation was reversed for singers, who were instructed to sing more strongly in solo passages than in ripieni.

In addition to these “block” dynamics which applied to entire phrases or sections, singers used several devices to give dynamic shape to individual notes or small groups of notes.

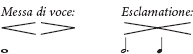

The swelling and diminishing of a tone, widely known as messa di voce, was in use from the beginning of the seventeenth century, though it was not known by this term until at least the 1630s. Caccini calls it simply il crescere e scemare della voce (increasing and diminishing of the voice), though he mentions it mostly to state his preference for a contrary effect called esclamatione (see below). Della Valle, in the passage cited above, uses a similar expression in relating that it was one of the devices brought to Rome by Emilio de’ Cavalieri in 1600. Mazzocchi appears to be the first to use the term messa di voce in 1638, but the ornament which he describes involves increasing (and only increasing) both the volume and the pitch of a note. Ornaments involving the gradual sharpening of a note by a diesis (half of a small semitone) or by a small (enharmonic) semitone are described by other writers from the 1640s and were used in passing from one note to its enharmonic upper neighbor (e.g., f to f#) Mazzocchi then describes the swelled note and indicates it in the music with the letter “C” (for crescere):

When, however, one is to increase only the breath and the spirit of the voice, but not its pitch, this will be indicated by the letter “C,” as was done in a few madrigals; and one should then observe that just as the size of the voice must first be sweetly increased, so must it subsequently be abated little by little, and so leveled off until it is reduced to the inaudible or to nothing, as from a well which thus responds to certain pitches.22

Interestingly, Mazzocchi applies the crescere almost exclusively to final notes.

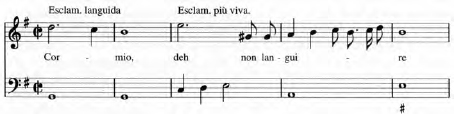

More popular in the early decades of the seventeenth century than the swelled note was the esclamatione. Caccini describes it in detail, claiming that it is the principal means of moving the affections. It consists, he says, in beginning a note by diminishing it—that is, beginning strongly and immediately tapering—so that one can then strengthen it and give it liveliness. Thus the form of the esclamatione is opposite to the messa di voce: the esclamatione is typically done on downward-moving dotted figures, usually consisting of a dotted half note with falling quarter or dotted whole note with falling half. The voice is diminished little by little and then is given more liveliness “in the falling of the quarter note”:

According to Caccini, a larger interval requires a more passionate esclamatione, as in Example 16.21.

Example 16.21. Giulio Caccini: “esclamatione” as found in Le nuove musiche (1602).

Esclamazioni are mentioned by many other writers, but none of them provides much new information about it, with the exception of Francesco Rognoni in 1620. Rognoni's description varies little from that of Caccini, but he adds that “one gives spirit and liveliness to the voice on the quarter note with a little tremolo.”23

We will discuss later what is meant by the tremolo itself, but in writing out these tremoli rhythmically, Rognoni gives an indication, as can be seen in Example 16.22, of the exact point at which the crescendo is to begin. Both of Rognoni's examples indicate that the tremolo, and thus the crescendo of which it is a part, is to begin on the dot of the first note.

Example 16.22. Francesco Rognoni: “tremolo” as found in Selva de varii passaggi (1620).

Ornaments of Fluctuation

Numerous techniques have been used throughout history both by singers and by instrumentalists to create fluctuations of pitch and intensity. These devices often represented part of an oral tradition (and thus remain frustratingly unelucidated in theoretical sources) but sometimes were personal and controversial. Being difficult to describe precisely, they frequently led to misunderstandings and terminological quagmires. In this the seventeenth century was no exception. Some of the techniques used around 1600 produce effects which we would normally call vibratos; others produce trills, note repetitions, and other effects strange to modern ears.

The term “vibrato” did not come into use until the nineteenth century, and the concept of vibrato as distinct from other kinds of fluctuations was foreign to the seventeenth-century musician. Thus an intensity variation produced by varying the bow pressure on a violin could share the same name as a whole-step trill on the organ: tremolo. To understand seventeenth-century ornaments, it is best to give up the term “vibrato” and concentrate instead on the devices and the techniques used to produce all sorts of tone fluctuations.

Most devices of this sort in the seventeenth century went under the name tremolo. Sometimes it refers to the kind of unmeasured “quivering” or “trembling” that Praetorius and others ascribe to good voices, particularly those of boys. Zacconi's discussion is particularly interesting because he credits this tremolo with a role in the production of the passaggi:

And in order not to leave out anything on this subject, for the great enthusiasm and desire that I have to aid the singer, I say in addition that the tremolo—that is, the trembling voice—is the true door for entering into the passaggi and for mastering the gorgie, because a ship sails more easily when it is already moving than when it is first set into motion, and a jumper jumps better if before he jumps he takes a running start.

This tremolo must be brief and graceful, because the overwrought and the forced become tedious and wearying, and it is of such a nature that in using it, one must always use it, so that its use becomes a habit, because that continuous moving of the voice aids and readily propels the movement of the gorgie and admirably facilitates the beginnings of passaggi. This movement about which I speak must not be without the proper speed, but lively and sharp.24

Other descriptions of the tremolo appear to impute to it a more measured, rhythmic nature. Rognoni gives an example of the vocal tremolo (Example 16.23) and says that “for the most part the tremolo is done on the value of the dot of any note”:

Example 16.23. Francesco Rognoni: “tremolo” as found in Selva de varii passaggi (1620).

Rognoni does not explain the technique used to produce the tremolo, but he does make a distinction between it and the trillo, saying that the latter is “beaten with the throat.” Thus the tremolo is presumably a smooth and regular fluctuation of intensity and/or pitch.25 It has, according to Rognoni, a special role in the production of the esclamatione, where a tremoletto26 is used to give liveliness to the voice at the point where the voice is to increase in volume.

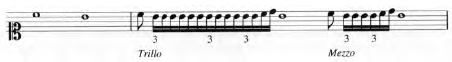

As opposed to the tremolo, which was unarticulated, the trillo is usually described as an articulated reiteration of a note “beaten in the throat”—that is, employing the same kind of throat articulation used for the execution of rapid passaggi.

The Roman falsettist Giovanni Luca Conforto was the first to notate it in his Breve et facile maniera of 1593. Conforto (see Example 16.24) uses a “3” to indicate that the repeated notes should be redoubled in speed27 (i.e., they should have three beams instead of the two that appear below them):

Example 16.24. Giovanni Luca Conforto: “trillo” as found in Breve et facile maniera (1593).

Conforto's trilli have terminations similar to the groppo and thus show some similarity to an ornament called the tremolo groppizato, which appears four years earlier in Girolamo Dalla Casa's Il vero modo di diminuir (Example 16.25).

Example 16.25. Girolamo Dalla Casa: “tremolo groppizato” as found in Il vero modo di diminuir (1584).

Although Dalla Casa uses the term tremolo instead of trillo, it is tempting, given the speed of the ornament and its similarity to later trilli, to think that it represents an early example of the articulated reiteration.

Caccini's well-known example of how to learn the trillo shows a gradual increase in the speed of the reiterated notes. In his more extended musical examples (see Example 16.26), however, Caccini indicates trilli on notes as short as a quarter note and often includes figures with only two note repetitions. In view of Conforto's use of the number 3 to notate a faster trillo than those indicated by the notes, it could be that Caccini intends for the repeated notes to be redoubled in speed and number, the two written-out repeated notes being a kind of shorthand for note repetition. This hypothesis is supported by Ottavio Durante, who, in reference to the indication t, remarks that where it is found, “one must always trill with the voice, and when it is notated above a trillo or groppetto itself, one must then trill that much more.”28

Example 16.26. Giulio Caccini: “trilli” as found in Le nuove musiche (1602).

Despite the many descriptions of “beaten” trilli, the term was not exclusively used for a repeated-note ornament. In the preface to Cavalieri's Rapresentatione di anima, e di corpo, the table of ornaments gives a trillo which is nothing but a trill with the upper neighbor, and Bartolomeo Bismantova uses the term in the same way in 1677.29

CONCLUSION

The ornamentation style discussed in this article was that used primarily by Italian singers from the last decades of the sixteenth century until roughly the mid-seventeenth century, when new influences, including those brought from the French court, began to modify vocal tastes and practices. Singers, however, were the model for instrumentalists as well, who were to imitate the human voice as much as possible. One of the most important ways of doing this was through the imitation and adaptation of vocal ornamentation. Thus Sylvestro Ganassi calls the tonguing used for division playing the lingua di gorgia after the throat articulations used by singers, and Francesco Rognoni says that his description of vocal ornaments is “something useful to instrumentalists as well for imitating the human voice.”30 Singing without ornaments can never have the required grace; instrumental playing without ornaments can never be truly vocal.

This ornamentation style was also exported, more or less intact, to Germany, where Italian singers and Italian styles dominated in the seventeenth century. German writers like Praetorius, Johann Andreas Herbst, and Johann Crüger give examples of ornaments such as the intonatio, accento, groppo, tremolo, and trillo that are virtually identical to those of the Italians.

NOTES

1. Della Valle, “Della musica”: 255–256 (page numbers refer to Doni, Lyra Barberina).

2. Zacconi, Prattica di musica vol. 1, libro primo, cap. 63.

3. For a fascinating discussion of sprezzatura, see Baldassare Castiglione, Il libro del cortegiano, Florence, 1528, libro primo.

4. It is interesting to note that Conforto was criticized by Pietro della Valle for his excesses in singing passaggi.

5. More about accenti below.

6. Scaletta, Scala di musica.

7. Barbarino, Motetti.

8. This is more a definition than a rule. An understanding of the concept of good and bad notes, the alternation of consonant notes on stressed beats with dissonant ones on unstressed beats, was fundamental to musical thinking in the sixteenth century and is a prerequisite to Virgiliano's next rule.

9. As can be seen from his examples, Virgiliano is speaking here of the ornamentation of whole notes. His battuta thus refers to the entire value of the note being ornamented.

10. The reason for this exception and its restriction to g′ is unclear to this writer. As an illustration of this point, Virgiliano has inserted in the text a musical staff with two semibreves, both on g′.

11. Scaletta, Scala di musica.

12. Opinions are mixed on the suitability of all the vowels for making passaggi. Durante take the negative view: “[Singers] must…make use of those [passaggi] that are most appropriate and that work best for singing, guarding against doing them, however, in places that obscure the intelligibility of the words, [and] particularly on short syllables and on the odious vowels, which are i and u, for the one resembles neighing and the other howling.” (Durante, Arie devote, preface.)

13. Zacconi, Prattica, vol. 1, prima parte, cap. 66. The facsimile of this treatise can be accessed at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58224g

14. Bovicelli, Regole, avvertimenti.

15. Ibid.

16. Scaletta, Scala di musica, in the section entitled “Ultimo avertimento, utilissimo ancora per tutti quelli che desiderano cantar polito & bene.”

17. Zacconi, Prattica, libro primo, cap. 63.

18. All ornamentation, of course, is difficult to fix into precise musical notation, but it seems to have been particularly true of the accento that its performance was meant to be free of a fixed rhythm. Words such as “lingering,” “clinging,” and “rather late” are frequently used to describe it, and we are frequently told that its exact nature can be appreciated only by hearing it done.

19. Rognoni Taeggio, Selva, avvertimenti.

20. Scaletta, Scala di musica: ch. 15.

21. Ganassi, Fontegara: ch. 1.

22. Domenico Mazzocchi, Madrigali a cinque voci (Rome, 1638), preface.

23. Rognoni Taeggio, Selva, avvertimenti. See Carter, “Rognoni.”

24. Zacconi, Prattica di musica, libro primo, cap. 66.

25. In instrumental music of the early seventeenth century, tremoli are often found written out in repeated eighth notes with or without slur marks (see Carter, “String Tremolo”). Such tremoli nearly always proceed continuously for the duration of an entire, brief section, often chromatic in character, and are quite clearly meant to imitate the organ tremulant. One sonata by Biagio Marini (La Foscarina, sonata à 3 from the Affetti musicali of 1617) even has an indication in the organ part to “turn on the tremolo” (metti il tremolo), while the violins have the instruction “tremolo with the bow” (tremolo con l'arco) and the fagotto, “tremolo with the instrument” (tremolo col strumento).

26. Sometimes the term tremoletto (lit., little tremolo) indicates a little trill of just two notes with the upper or lower neighbor.

27. Conforto/Stevens, Joy: 28.

28. Durante, Arie devote, preface

29. Bismantova, Compendio [23].

30. Rognoni Taeggio, Selva, title page.

SELECTED READING LIST

The reading list below includes the most important Italian sources on singing between 1590 and 1680. Where facsimile editions or English translations are not available, the original texts of prefaces may often be found in the published catalog of the Civico Museo Bibliografico in Bologna, which has original copies of most of these works. Some prefaces are also found in Claudio Sartori's Bibliografia della musica strumentale italiana, though Sartori is less generous with prefaces to the reader than with dedications. The list also includes several German sources which have extensive information on Italian singing style, as well as two invaluable German secondary sources which include extensive citations of sources in the original Italian.

Original Sources

1592 Zacconi, Lodovico. Prattica di musica. Venice. Partial German trans. by F. Chrysander, “Lodovico Zacconi als Lehrer des Kunstgesanges,” Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft 7 (1891): 337–396; 9 (1893): 249–310; and 10 (1894): 531–567 Facsimile ed. Bologna: Forni, 1983; digital reproduction at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58224g.image.f2.tableDesMatieres

1593 Conforto, Giovanni Luca. Breve et facile maniera. Rome. Facsimile ed. with German trans. by J. Wolf (Berlin: Breslauer, 1922); facsimile. rep., ed. Denis Stevens as The Joy of Ornamentation. White Plains, N.Y.: ProAm Music Resources, 1989. Eng. trans. of preface by Stewart Carter in review of Stevens's edition. Historical Performance 5/1 (1992): 50–54.

1594 Bovicelli, Giovanni Battista. Regole, passaggi, di musica. Venice. Facsimile by N. Bridgman, Documenta Musicologica (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1957).

1598 Scaletta, Oratio. Scala di musica. Verona. Facsimile ed. of the 1626 edition. Bologna: Forni, n.d.

1600 Caccini, Giulio. L'Euridice composta in musica. Florence. Facsimile ed. Bologna: Forni, 1976.

1600 Cavalieri, Emilio de'. Rappresentatione di anima, e di corpo. Rome. Facsimile ed., Farnborough, 1967

1602 Caccini, Giulio. Le nuove musiche. Florence. Anon. English trans. called “A Brief Discourse of the Italian Manner of Singing…” In J. Playford, Introduction to the Skill of Music, 10th ed. London. Rev. ed. of above in Strunk, Source Readings—Baroque. English trans. in Newton, Nuove Musiche. Modern musical edition with English trans. in Hitchcock—Nuove Musiche. Facsimile ed. by F. Mantica, preface by G. Barini. Rome, 1930. Facsimile ed. by F. Vatielli. Rome, 1934. Digital reproduction can be accessed at http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/b/bf/IMSLP56498-PMLP116645-Caccini_Le_nuove_musiche.pdf

1608 Durante, Ottavio. Arie devote, le quale contengono in se la maniera di cantar con gratia. Rome.

1609 Banchieri, Adriano. La cartella. Venice. Facsimile of 1614 ed. Bologna, n.d.; digital reproduction can be accessed at http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/e/e6/IMSLP23500–PMLP53564-cartella_musicale_1614.pdf

1612 Donati, Ignazio. Sacri concentus. Venice.

1614 Brunelli, Antonio. Varii esercitii…per…aqquistare la dispositione per il cantare con passaggi. Florence.

1614 Barbarino, Bartolomeo. Il secondo libro delli moteti…da cantarsi à una voce sola ò in soprano, ò in tenore come più il cantante si piacerà. Venice.

1615 Severi, Francesco. Salmi passaggiati per tutte le voci nella maniera che si cantano in Roma. Rome.

1618 Puliaschi, Giovanni Domenico. Musiche varie a una voce. Rome.

1619 Praetorius, Michael. Syntagma Musicum III, Termini Musici, Wolfenbüttel. Facsimile ed.: Kassel, 1958 and 2001 (paperback). Digital reproductions of the second two volumes can be found at http://www.archive.org/stream/SyntagmaMusicumBd.31619/PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB3#page/n0/mode/2up or http://www.archive.org/details/SyntagmaMusicumBd.21619 and at: http://www.archive.org/stream/SyntagmaMusicumBd.21619/PraetoriusSyntagmaMusicumB2#page/n0/mode/2up or http://www.archive.org/details/SyntagmaMusicumBd.21619

1620 Rognoni Taegio, Francesco. Selva de varii passaggi. Milan. Facsimile ed. with preface by G. Barblan (Bologna, 1970).

1638 Mazzocchi, Domenico. Dialoghi, e sonetti. Rome. Facsimile ed. Bologna, n.d..

1638 Mazzocchi, Domenico. Partitura de’ madrigali a cinque voci, e altri varii concerti. Rome. Facsimile ed. Bologna, n.d.

1640 Della Valle, Pietro. “Discorso della musica dell'età nostra…“ in G. B. Doni, Lyra Barberina, vol. 2. Florence, 1640. Facsimile ed. with commentary by C. Palisca. Bologna, 1981.

1642 Herbst, Johann Andreas. Musica practica sive instruction. Nuremberg.

1660 Crüger, Johann. Musicæ practicæ præcepta…Der rechte Weg zur Singkunst. Berlin.

1677 Bismantova, Bartolomeo. Compendio musicale. Ferrara. Facsimile ed. with preface by M. Castellani. Florence: S.P.E.S, 1978.

Secondary Sources

Brown, Embellishing; Gaspari, Catalogo; Goldschmidt, Gesangsmethode; Kuhn, Verzierungs-Kunst; Sartori, Bibliografia.