First Days at Okinawa

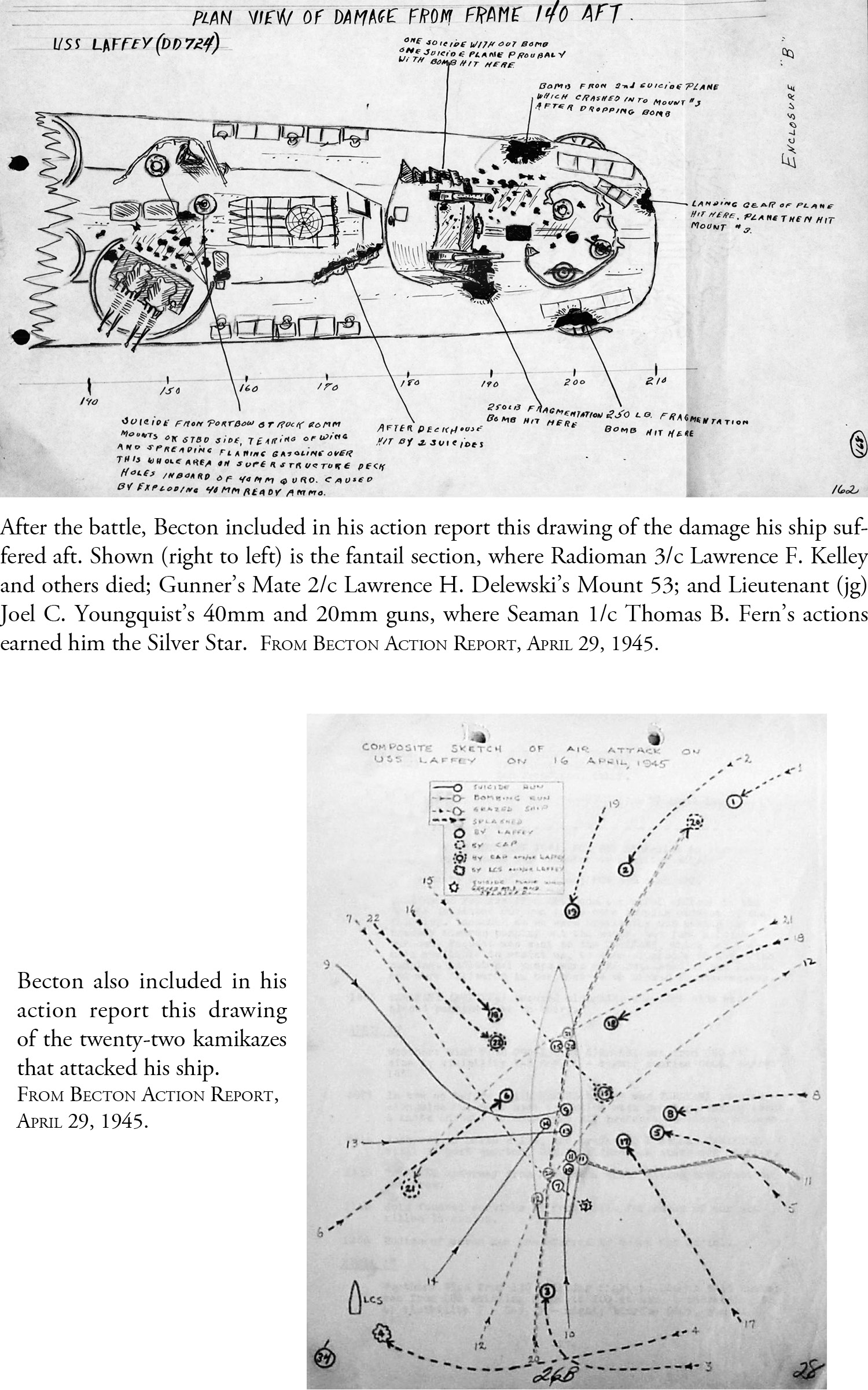

After striking Nippon’s home

Off Iwo Jima she did roam.

Then Okinawa to be eyes

And guns to clear the hostile skies.

—“Invicta,” Lieutenant Matthew Darnell

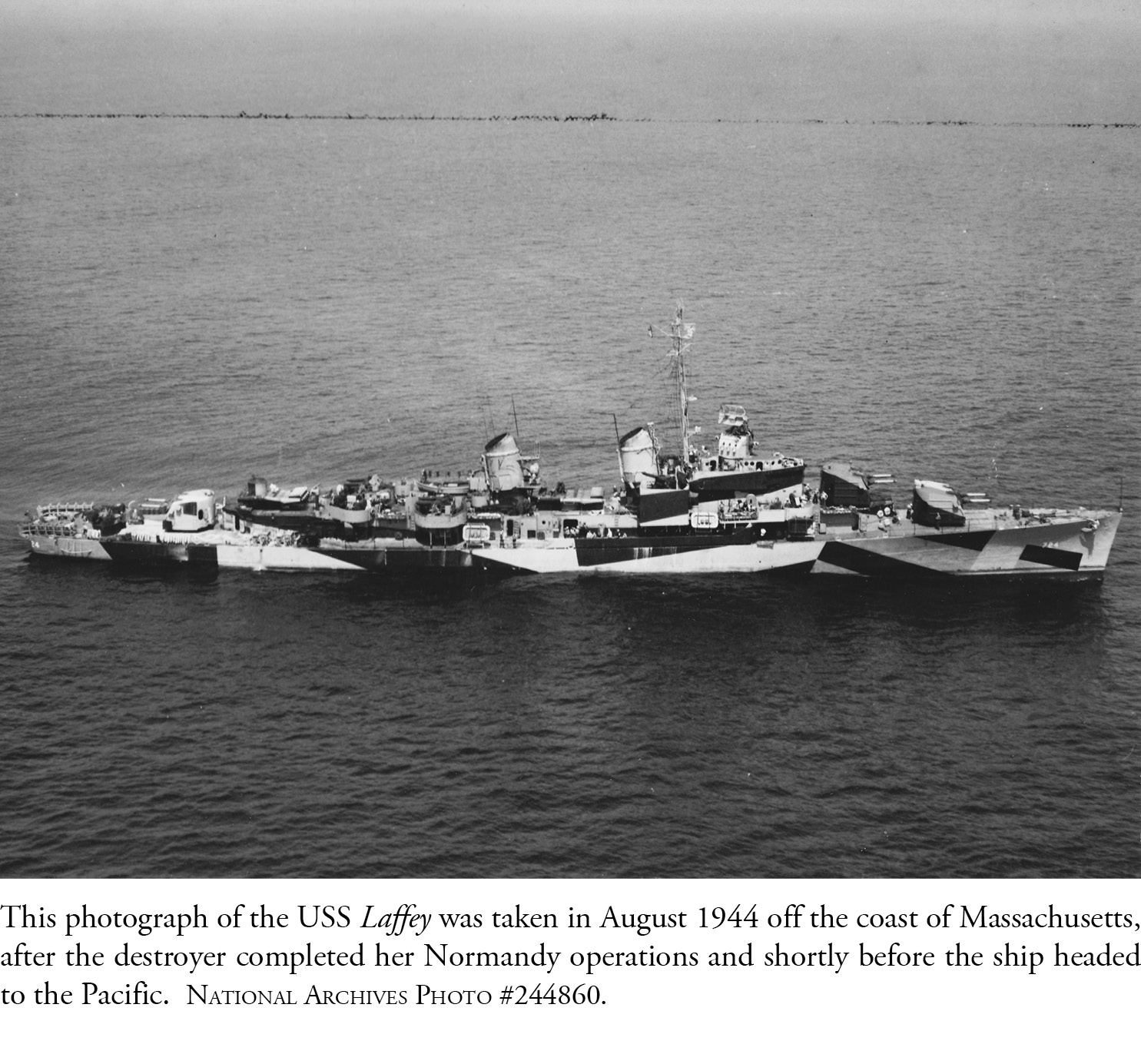

In late morning on March 2, Laffey entered Mugai Channel of Ulithi Atoll. The men had never seen anything like the vast anchorage, filled with ships of every sort. A part of the vast Caroline Islands chain located 850 miles east of the Philippines, Ulithi, a volcanic atoll with coral islands, sand, and palm trees, encircled an anchorage fifteen miles across. “It was huge,” said Sonarman Zack. “The entire task force could fit inside it.”1 Seabees constructed an airstrip on Falalop Island in the northeast, headquarters on Asor to its west, an advanced base hospital and ship repair facilities on Sorlen to the north, and—the reason most sailors looked forward to a stay at Ulithi—recreational facilities and beer on Mog Mog.

To sailors accustomed to weeks and months at sea, where death was a constant, Mog Mog was paradise. Though a minority, like Massachusetts native Tom Fern, wished for a little snow to break the sultry monotony, most men joked that it offered their four favorite “Bs”—bathing, baseball, boxing, and beer. Golden beaches and their luscious sand replaced the unforgiving decks of destroyers and cruisers, deep blue waters offered the chance for a refreshing swim, and cooks handed out ice cream, pies, and cake. Mog Mog’s beer bars—little more than wooden stands set up to handle the eighteen to twenty thousand men who packed the island, dispensed two bottles of warm beer to each enlisted. Officers enjoyed their own facility where they could purchase a shot of Scotch for twenty cents and enjoy the company of Navy female nurses. Basketball courts, baseball diamonds, and a football field offered recreation for the athletically inclined, while a movie theater and a small chapel enticed those who sought more passive endeavors. Even former heavyweight boxing champion, Gene Tunney, who had twice defeated Jack Dempsey in compiling a sixty-five-win career, was there to arrange recreation events for the thousands of sailors. Until late that afternoon, when everyone had to return to his ship, Mog Mog provided a safe haven from the war. For the next seventeen days Fern, Johnson, and their shipmates could take their minds off kamikazes and bloodshed and be youngsters again.

To provide stability to a novice crew and to give the men time to gel into an efficient team, for the first year of a new ship’s existence, Navy policy dictated that no officers would be transferred. As a year had now passed since Laffey’s February 1944 commissioning, Becton lost his executive officer, Lieutenant Charles Holovak, who received command of his own ship, and his gunnery officer, Lieutenant Harry Burns, who became an executive officer elsewhere. Although Becton would miss the capable officers their replacements, Lieutenant Challen McCune Jr. as his new second in command and Lieutenant Paul B. Smith as gunnery officer, ably slipped into their new duties. Tougher to replace was the group of senior petty officers and other experienced men the Navy shifted to man the vessels coming out of shipyards.

During their stay at Ulithi the crew selected an emblem for Laffey: a black tiger with glaring yellow eyes and menacing fangs chewing on a twisted Japanese plane. The symbol was a natural outgrowth of Becton’s wish to operate an aggressive ship that took the fight to the enemy, similar to a tiger attacking its prey, and recognition of the obvious role that Japanese aircraft had in Pacific combat. “It means we’re bad luck, or death, to Jap planes,” Seaman 1/c Ernest E. Belk later explained. “We didn’t know how appropriate it was going to be, though.”2

Although kamikazes had been largely absent from the air strikes against Tokyo and their operations off Iwo Jima, they could not be discounted, even at Ulithi, distant from the combat zone. On March 11, while the crew watched a movie on the forecastle, general quarters sounded. Men rushed to battle stations as Lieutenant Iroshi Murakawa and eleven enemy aircraft from the Mitate Unit No. 2 dived on the carrier USS Randolph (CV-15). One barreled through heavy antiaircraft fire and smashed into the carrier’s starboard side just below the flight deck, killing 27 and wounding 105.

The next day Becton called Lieutenant Manson and Lieutenant Henke to his cabin. With only one more weekend in Ulithi before the planned Easter Sunday attack on Okinawa, Becton wanted a religious service for his crew before they left for what could be their toughest operation to date. “Look at that attack yesterday,” he remarked to the pair. “If eight hundred miles of ocean won’t stop them from trying, we are going to need help.”

He asked Manson and Henke to organize an Easter service on the final Sunday, March 18. They turned to Seaman Belk for assistance, and together the three assembled a moving ceremony held three days before the ship left Ulithi. Lieutenant Henke read prayers, and Radioman 3/c Lawrence F. Kelley, whose heart-wrenching tenor voice had often entertained the crew in late afternoon sessions on the fantail, sang several religious pieces before turning to the popular “I’ll Be Seeing You.” The powerful song about a person who, although far from his loved one, sees her image wherever he turns, moved those who attended and had men thinking of family and loved ones. Lieutenant Youngquist, who attended every service held aboard Laffey, noticed an increased attentiveness in the men who would soon be entering combat. “I suppose there have been many grander and more impressive religious services held to celebrate Easter and to invoke the Almighty’s blessing,” wrote Becton. “But I doubt if any has ever been more sincerely touching than the one we had aboard the Laffey about two weeks before we sailed into hell.”3

As Ulithi and its pleasures slipped from view, the crew’s thoughts turned to the upcoming Okinawa operation. Facing another lengthy operation at sea, Seaman Fern had already dispatched a letter imploring his parents, “don’t be mad when you don’t get any letters for a while.”4 Men held mixed opinions as to what they might encounter. Kamikazes had been active while Laffey covered three Philippine landings, but had been conspicuously absent during their raids against Japan and off Iwo Jima. Most assumed the weapon was certain to appear, but hopefully the numbers would not compare to what they had witnessed off the Philippines.

Some argued that luck had so far sheltered the ship and crew. During stretches of time when kamikazes dived on battleships and smashed into cruisers, Laffey emerged unscathed, first off the Philippines and then again off Japan and Iwo Jima, apparently being one of those vessels good fortune favored. “At that time of our lives,” said Seaman Martinis, “we considered ourselves indestructible. Kamikazes wouldn’t happen to us.”5

“It May Be a While Before You Hear From Me”

The United States gathered an immense force to seize Okinawa. More than twelve hundred ships, including eighteen battleships, two hundred destroyers, and over forty aircraft carriers escorted and transported the assault troops to the island. So great was the armada that forces had to assemble at almost every major US port in the Pacific, including locations in the Marianas, the Philippines, the Solomons, Hawaii, and the West Coast. Under the command of Admiral Spruance, the hero of Midway, and Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the naval units rivaled those employed in the massive European D-Day operation staged at Normandy.

The campaign for Okinawa was the most recent in a long string of operations that shoved the Japanese out of the island bastions they proudly held in early 1942. Beginning in the Solomons, United States land and sea forces gradually leapt westward and northward in a simultaneous advance along two Pacific paths, gobbling up the Gilberts, the Marshalls, the Marianas, New Guinea, the Philippines, and Iwo Jima in the process. Now, they were poised to grab Okinawa, practically on the doorstep of Japan. Once successful, the Americans intended to use Okinawan airfields to house bombers to attack Japan, and Okinawa itself as a major staging area for the massive numbers of men, ships, and supplies required for the landmark invasion of Japan.

The Japanese considered Okinawa to be a part of Japan proper. American planners accordingly assembled a powerful landing force to counter the thousands of enemy soldiers defending the island. Three Marine and four Army divisions would land on Okinawa’s western coast before splitting, with the Marines clearing out the northern part of Okinawa while the Army secured the south.

The Navy’s role varied little from earlier assaults. Admiral Mitscher’s carrier aircraft would conduct preliminary strikes against Formosa, Okinawa, and Tokyo and other strategic points in the Home Islands before turning south to support the April 1 landings. In the meantime Laffey, no longer with Mitscher’s fast carriers, would join other ships to provide supporting gunfire to the landing force.

Suicide aircraft were on the minds of every American naval commander assigned to be a part of the operation. During a March 10 meeting, while Laffey’s crew rested at Ulithi, Admirals Nimitz, Spruance, and Mitscher expressed their concerns over the expanding toll of the Pacific War. Marines had suffered hideous casualties at Saipan, Iwo Jima, and other locations. Due to kamikaze attacks an increasing number of naval vessels had either limped back to port for repairs or wound up on the ocean’s bottom. Mitscher warned the group to expect hundreds, if not thousands, of kamikaze aircraft during the Okinawa operation.

Three days later Mitscher guided Task Force 58 out of Ulithi on its pre-invasion mission of hitting Kyushu airfields, but suffered severe losses when Japanese bombers hit the carriers USS Wasp (CV-18) and Franklin on March 19. One bomb forced Wasp to return to the States for repairs, while two bombs ripped through the Franklin’s hangar deck, igniting gasoline-laden aircraft and demolishing the CIC. The Japanese pilots succeeded in killing more than seven hundred crew and knocking two vessels out of the war. The event showed how prepared the enemy was two weeks before the invasion, portending difficult times for Laffey and fellow vessels when they prowled the waters off Okinawa.

As much as the United States wanted Okinawa, the Japanese intended to prevent its loss. To them, retaining the island was a matter of honor and pride. Standing merely 350 miles south of Kyushu, Okinawa was considered one of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures. Assaulting it would be akin to attacking Tokyo. The Japanese boasted that in their long history the Home Islands had never been invaded, but should Okinawa fall, little remained to stop the Americans from doing exactly that. The Japanese military would turn to any measure, any last resort, to prevent the unthinkable from occurring. On March 20, one day before Laffey left Ulithi for Okinawa, Imperial General Headquarters labeled the island “the focal point of the decisive battle for the defense of the Homeland”6 and marshaled every weapon at their command to repel the invaders.

Desperate times called for desperate measures. Imperial General Headquarters realized the enemy would come for Okinawa, but they lacked the necessary resources to stop them. Serious shortages existed in ships, oil, bombs, and bullets. Japanese factories, once humming with activity, now labored under devastating American bombing raids to produce a fraction of what they had previously manufactured. Placed in a precarious situation, the Japanese hoarded their remaining aircraft and turned to the one commodity they possessed in abundance—volunteers willing to die for their country and their Emperor by piloting aircraft into enemy ships. One aircraft, one ship—a simple equation that, if successful, might reverse fortune for the reeling Japanese.

In a March 29 meeting, Emperor Hirohito admonished his military commanders to adopt every possible measure to halt the United States. They informed him that because of the disastrous naval clashes in the Philippines, few surface forces were available, but that more than three thousand kamikaze aircraft stood ready to meet the Americans at Okinawa.

As Imperial General Headquarters stated in outlining the new plans, “there was no longer any alternative to general use of special attacks, in which even inexperienced pilots could score a hit.”7 The plan, named Ten Go (“Heavenly Operation”), earmarked a series of colossal air raids, called kikusui (“floating chrysanthemums”), to assault enemy ships off Okinawa. The newest aircraft and most experienced pilots would be retained in the homeland to defend Japan’s shores, but otherwise every available aircraft, including seaplanes, outdated fighters, training planes, and scout planes, was sent to Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki’s Fifth Air Fleet in Kyushu for use off Okinawa. Despite being given little training in flying, men willing to gain honor by yielding their lives quickly filled the kamikaze corps.

“As the air raids on the Japanese archipelago intensified, we noticed a definite change in the morale of the kamikaze volunteers,” said Captain Rikihei Inoguchi, the senior staff officer to Admiral Onishi. “They became more desperate than ever. They became more agitated emotionally by the conviction that only by their deaths could the fatherland be saved from imminent destruction.”8

Japanese soldiers fighting on Okinawa planned to slow the American advance on land with a series of defense lines anchored along Okinawa’s numerous ridges and throughout the island’s elaborate network of caves. In stalling the American drive on land, they would force American ships to remain offshore to lend air support, thereby turning them into tempting targets for kamikaze attacks. Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, commander of the Japanese defenders on Okinawa, exhorted his men to a spirited defense by heralding the feats of their brethren in the skies. “The brave, ruddy faced warriors with white silken scarves tied about their heads, at peace in their favorite planes, would dash spiritedly out to the attack.”9 Ushijima counted on the kamikazes to so seriously impede US naval support for the forces ashore that he would be able to defeat the Marines and Army infantry.

American ships and sailors would pay a heavy price as a result. “In the Ryukyus,” remarked Vice Admiral Seiichi Ito on April 2, “we can best break the enemy’s leg.”10 Ito would soon command Japan’s final surface foray at sea.

One of the subjects of Ito’s scorn, Tom Fern, only knew that he was again venturing into combat. He wrote his mother on March 21, “it may be a while before you hear from me after this—haven’t got time to write you a regular letter so this will have to do.”11 Fern planned to send a longer letter as soon as he returned from the assignment, but for now his mother would have to be satisfied with the few words he could provide. Seaman Fern wished he could impart more, but the Navy clamped a tight lid on information. Outside of Becton, no one in the crew knew much about operations anyway. His mother would need to endure the coming weeks without knowing whether her boy was safe, a burden shared by other mothers and fathers throughout the United States.

“Lone Ranger Duty”

Laffey left Ulithi as part of Task Force 54, the largest bombardment group yet assembled in the Pacific, commanded by their old friend from Normandy days, Rear Admiral M. L. Deyo. Eighty-three ships, including ten battleships and ten cruisers screened by Laffey and twenty-three destroyers, exited the anchorage on March 21 to begin the three-day journey to Okinawa. The long line of warships impressed observers on shore, who watched the latest conglomeration of American military might—further proof of American industrial capacity—sweep into Pacific waters.

From other ports and anchorages troop transports, crowded with Army infantry or Marine units, bore the invasion forces toward Okinawa. Knots formed in stomachs and thoughts turned to family and home as the ships moved closer to the island, for whether Marine or Army, all had heard of the carnage that marked the most recent operation against Iwo Jima. This assault was likely to bring more of the same.

The Laffey crew held a different perspective as they took their ship to sea. Although they could not forget what had happened to the landing forces at Iwo Jima, at least the air opposition, the part with which they were most concerned, had slackened. Compared to what they had encountered off the Philippines, the enemy’s air response during their raids against the Tokyo area and during the Iwo Jima operation had been surprisingly light. As far as the men were concerned, they would most likely encounter the same lack of air attack at Okinawa. Sonarman Zack expected some aerial fireworks to occur, only because they were moving closer to Japan and the enemy had already proven willing to resort to desperate measures, but few thought that squadrons of kamikazes would descend on them as they operated off the island.

Late in the afternoon Becton proceeded to his assigned station twelve miles ahead of the task force, forming the vanguard of Deyo’s assemblage as it churned toward the island. The next day Becton conducted drills simulating a bomb hit near his forward five-inch gun mount and a suicide crash into the base of the number one stack. Most of the crew read nothing into the exercises—Becton had, after all, kept them busy with drills since the ship’s commissioning—but the skipper’s choices that day proved prophetic.

Largely due to Mitscher’s carrier aircraft and Army B-29 bombers, Task Force 54 arrived in Okinawa waters late on March 24 without being attacked. Intelligence estimated that airfields on Okinawa, Formosa, and Kyushu housed as many as three thousand Japanese planes. To neutralize that weapon, on March 23 Army and Navy aircraft opened a series of air strikes to destroy those kamikazes before they lifted from the runways.

As American aircraft pounded enemy airfields, on March 25 five ships, including two cruisers screened by Laffey and two other destroyers, detached from Deyo’s main force and proceeded toward Kerama Retto, a cluster of ten rocky islands fifteen miles off Okinawa’s southwest coast. The islands, which fashioned a sheltered harbor large enough to anchor seventy-five ships, would serve as an advanced fueling and resupply base as well as a repair center for any ships damaged during the operation.

The March 26–29 seizure of these islands by the Army’s 77th Division, backed by Laffey and the detached force, proved to be a sideshow to the main landings at Okinawa a few days later, but it reaped welcome dividends at minimal cost. The crews of numerous destroyers, including Laffey’s, would frequent the anchorage’s repair facilities in the weeks to come. In addition, the infantry stumbled upon a surprise when they unearthed 350 suicide boats, camouflaged and hidden in caves. The plywood craft, eighteen feet long and five feet wide, each carried two 250-pound depth charges. Had the boats remained undiscovered, the Japanese planned to steer the craft toward the numerous troop-laden American transports floating in the waters near Okinawa. Those craft would now pose no threat to the landing force as it neared Okinawa.

Laffey again executed a variety of assignments during three weeks off Okinawa. Patrolling for enemy submarines occupied some days, while shore bombardments, night harassing fire, and screening filled the rest. As dusk approached, they joined with other ships in a circular cruising disposition designed for enhanced antiaircraft defense, and retired seaward for the night.

They started March 26, when they joined one battleship, two cruisers, and two destroyers to patrol the area southwest of Kerama Retto. While the Laffey crew enjoyed a quiet day, a kamikaze crashed into the aft gun mount of the USS Kimberly (DD-521), a destroyer screening with a different unit, killing four and wounding fifty-seven. This initial attack on a picket ship off Okinawa spared Becton and his crew, but he remarked that it “was a nasty hint of what was to come.”12

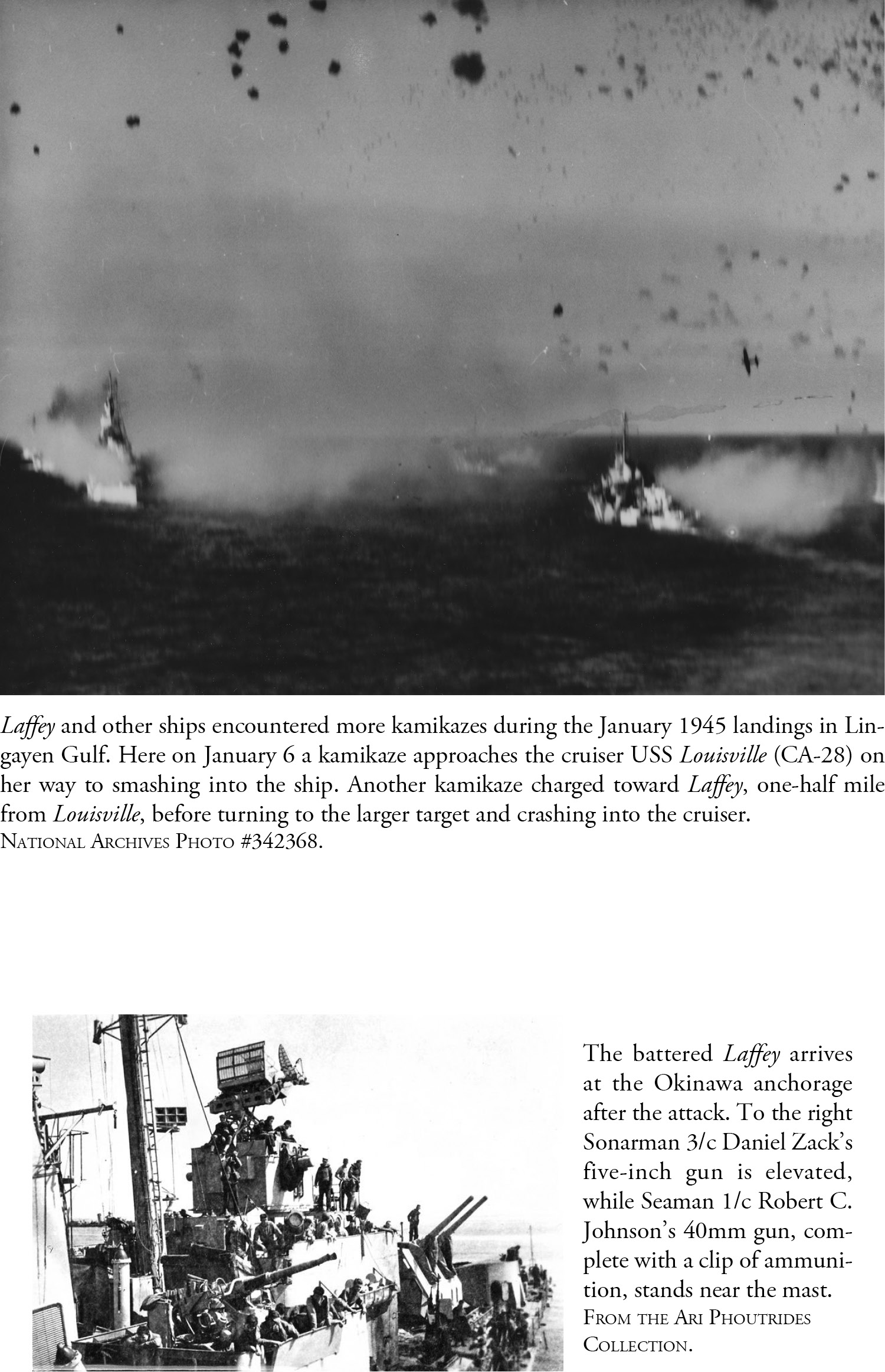

Any lingering hopes among the crew that the kamikaze threat had dissipated ended early the next morning when seven Japanese aircraft damaged five ships, including the venerable battleship USS Nevada (BB-36), which lost eleven men killed and forty-nine wounded. Most wrenching, as far as Laffey crew were concerned, was the loss of their sister ship, O’Brien. After being constructed at the Bath Shipyard, the two had operated together in both the European and the Pacific theaters. Men from both ships had mixed with each other during shore liberties, and at sea delivered mail and exchanged personnel. The crews had already lost two ships from DesDiv 119—German mines and bombs sank Meredith off the coast of France, while kamikazes badly damaged Walke at Lingayen Gulf—and the third was now removed on March 27 when a sole kamikaze bore through thick antiaircraft fire and crashed forward of amidships on O’Brien’s port side. Fifty men were killed or missing and another seventy-six were wounded. Thirty-six minutes later a second kamikaze dived at Laffey, but gunfire from adjoining ships splashed the intruder two miles short of its target.

Action intensified March 28–29 when Laffey joined two battleships, one cruiser, and two destroyers and proceeded to another screening position ten miles west of Naha on Okinawa’s western side. While the larger warships conducted a seven-hour bombardment of the Naha area, Laffey scoured the sea and sky for enemy patrol boats, submarines, and aircraft. All guns were manned and ready to fire, but no threat appeared until late that night. As the unit retired seaward for the night, Laffey’s radar picked up an enemy plane at twenty-five miles. Four minutes later, Becton ordered his forward five-inch guns to commence firing, and for the first time in the Okinawa campaign, Laffey’s forward gun mount crews jumped to action. The powerful guns trained on the incoming plane and boomed a line of shells toward the enemy, turning away the plane after firing more than one hundred rounds in four minutes. Shortly after midnight on March 29, Becton investigated a sonar contact that appeared at thirteen hundred yards, and two hours later a bogey closed to within seven miles before ship antiaircraft fire brought it down.

The next day Laffey left the formation to refuel at Kerama Retto. Ships of all sorts darted about the busy anchorage, filled mostly with vessels in need of repair from kamikaze damage or requiring more ammunition and supplies. Most men aboard Laffey took only a cursory glance at the hobbled ships, as they were preoccupied with replenishing their vessel. After refueling, the ship steamed to that day’s patrolling station five miles northwest of Kerama Retto.

On March 31 Laffey patrolled off southern Okinawa when a kamikaze struck Admiral Spruance’s flagship, USS Indianapolis (CA-35), forcing the cruiser out of action for repair. Spruance switched his flag to New Mexico (BB-40), but the incident illustrated that in the waters off Okinawa, no one was safe, from the lowest rank up through the commanding officer.

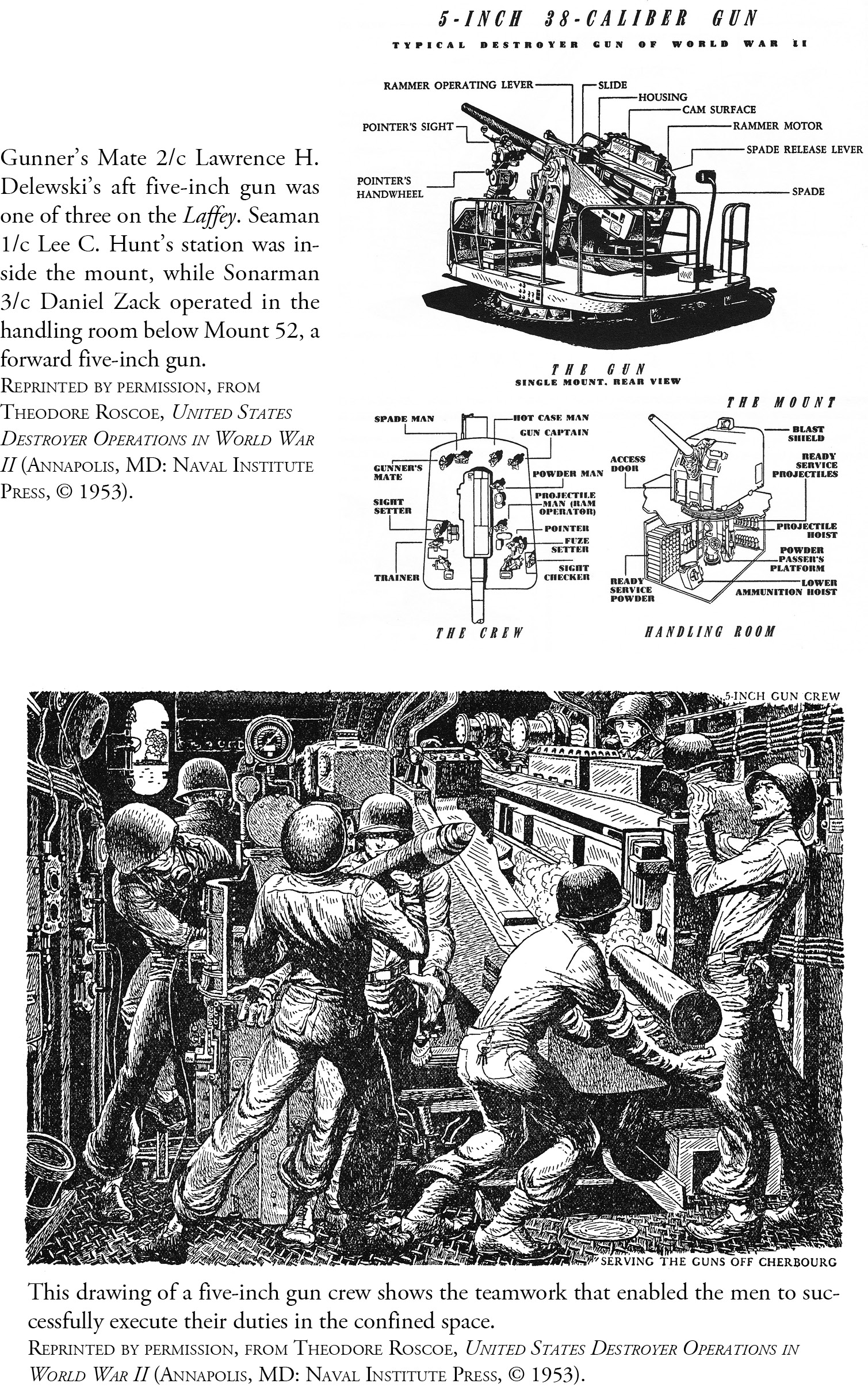

As evening approached, Laffey left to conduct night harassing fire on Japanese positions ashore, a potentially dangerous mission that often required the ship to operate alone. “We called it Lone Ranger duty,”13 recalled Gunner’s Mate Lawrence Delewski, the gun captain of Mount 53, because it reminded men of the famous Wild West cowboy riding alone into hostile lands. Becton carried out his mission without mishap, however, and all attention switched to the following day.

“Every Skipper Dreaded the Assignment”

Landing day, April Fool’s Day, offered a cruel irony of its own by kicking off what would become one of the bloodiest land and sea operations of the war on one of its holiest of religious days—Easter Sunday. The day began with a 1:24 a.m. report of an enemy submarine prowling in the area, a report lent credence when a torpedo crossed the bow of the USS Longshaw (DD-559), a ship operating in conjunction with Laffey. The pair moved closer to shore to conduct harassing fire against enemy positions, with one ship screening seaward while the other fired her guns, then switching positions.

Shortly after dawn Becton took Laffey from the main landing site on Okinawa’s west coast and headed to their decoy station in the southwest portion of the island. Although the main landings would occur in Hagushi Bay to the northwest, Laffey and other ships were designated to conduct a feint in hopes of tricking the Japanese into thinking the landings would happen in the south. Two minutes after turning southwest, Laffey radar spotted a bogey twenty miles out. Becton ordered his two forward five-inch guns to prepare to fire, and two minutes later, with the bogey now only seven miles out, the gun crews commenced fire. After firing forty-six shells in one minute the guns fell silent when the bogey turned away.

One hour later Becton placed his ship in position off the decoy beaches, where his gun crews began a busy day of firing toward shore targets. “We were deployed south,” said Seaman Martinis, who became a renowned heart surgeon after the war, “and bombarded the south end of the island for several days. Our group was a decoy to get the Japanese to think we were hitting there.”14 Quartermaster Phoutrides and others on the deck watched landing craft approach the line of departure as if infantry was to land, then turn away at the last minute instead of continuing toward shore.

As Laffey engaged in her feint, the main landings unfolded smoothly. Japanese General Mitsuru Ushijima had left a token force at the beach so he could concentrate his forces at well-entrenched defensive positions inland, where he hoped to delay the assault as long as possible by making the Americans pay dearly for every yard they seized. In retarding the American land advance, as planned Ushijima would force his enemy to hold its fleet offshore, making the ships vulnerable to the kamikaze aircraft gathered at Kyushu airfields.

That morning the first American wave hit the beaches, rushed inland, and within ninety minutes seized Yontan and Kadena airfields. Kamikazes smashed into a battleship and an LST killing sixteen, but the rain of kamikazes many feared would strike the fleet had not materialized.

In fact the first five days of the Okinawa operation, from the April 1 landing through April 5, hinted that their stay might not be difficult. No kamikaze threatened the ship, and one might have thought Laffey maneuvered off the coast of France, where despite the carnage occurring ashore, the destroyer faced minor opposition.

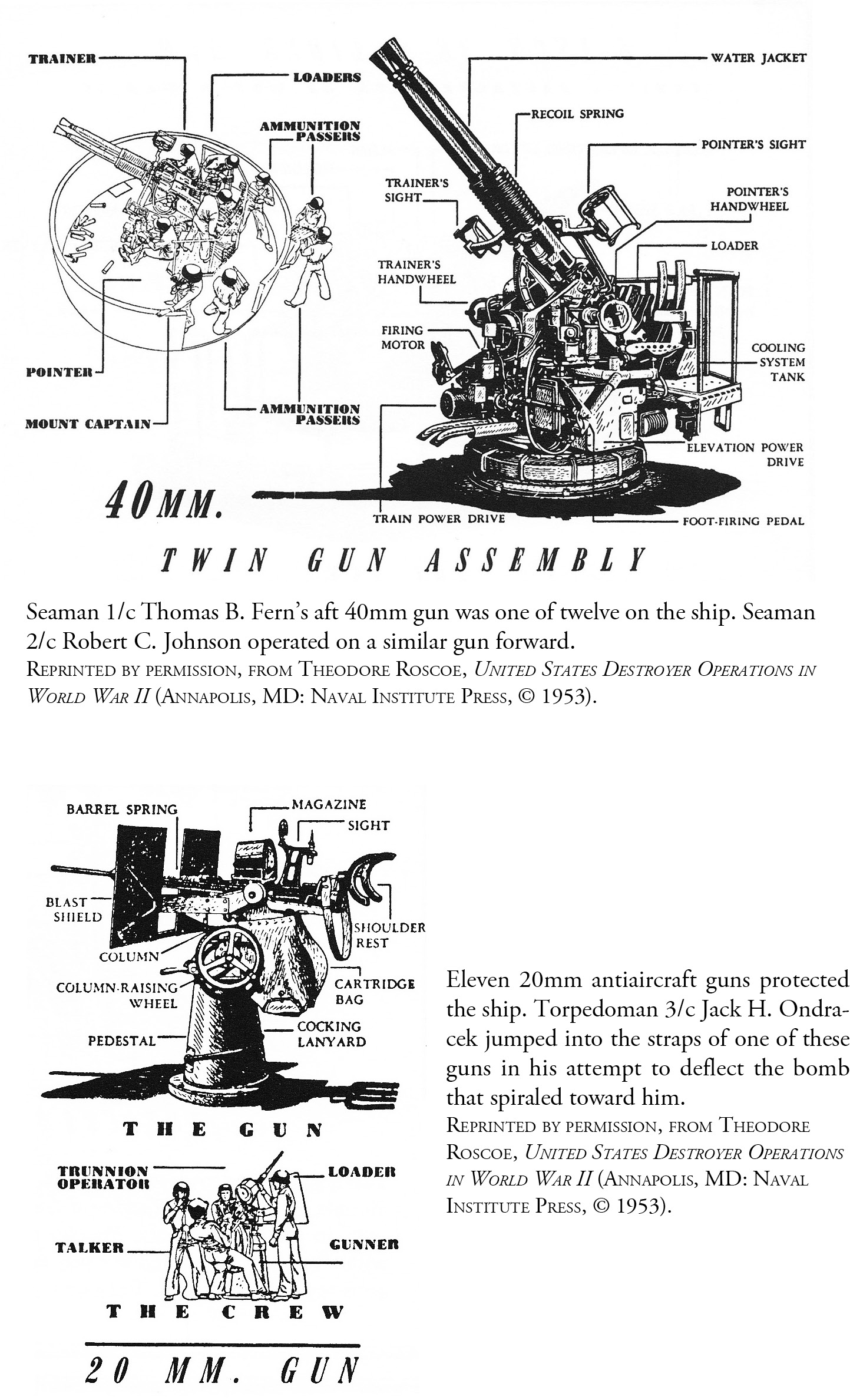

On April 3 Becton moved Laffey to the island’s western side, where for the next three days she continued to bombard land targets and conduct nighttime harassing fire. On April 3, her five-inch guns expended 413 shells in two separate bombardments, while her 40mm and 20mm guns exploded a floating mine.

Radar operators aboard the destroyer enjoyed a breather, as no enemy plane approached Laffey, but the same did not hold true elsewhere. On April 3 gunners aboard the USS Prichett (DD-561), stationed far to the north at Picket Station No. 1, the location closest to Hyushu and thus the most exposed to kamikaze attacks, splashed two aircraft, but not before sustaining damage from a bomb. Later in the day the USS Mannert L. Abele (DD-733), in Picket Station No. 4 off Okinawa’s northeast coast, shot down two aircraft.

Becton kept his crew sharp, for no matter where the ship operated off Okinawa, kamikazes remained a constant threat. Everyone admitted, though, that the stations to the north, particularly Picket Station No. 1, justifiably bore the reputation as being the most dangerous assignments near Okinawa. Destroyers screening at the northernmost post almost begged kamikazes to take a crack at them.

Though Picket Station No. 1 offered its perils, any of the sixteen radar picket stations that ringed Okinawa along the most likely air routes leading to the island offered challenges to the destroyers posted there. Part of the Navy’s plan to defend troop transports, landing craft, and other ships operating closer to shore, the destroyers on picket stations, placed at distances between fifteen and seventy-five miles off the island’s coast, provided an early warning system against incoming Japanese aircraft. Once their radar screens picked up enemy planes, they alerted other ships off Okinawa and vectored the CAP toward the intruders.

Unlike earlier assaults, where American air power and carrier aircraft helped neutralize Japanese air opposition, Okinawa’s proximity to the Home Islands placed it within easy striking range of Japanese aircraft based in Japan and Formosa. Crafty camouflage and widespread dispersal of kamikaze aircraft made it difficult to spot them from the air, and Japan housed aircraft at so many airstrips that American fighters and bombers could not possibly eliminate them all. Placed in such a quandary, the US Navy had no alternative but to remain off Okinawa to provide air support for the troops ashore, a distasteful prospect to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Admiral Spruance, who knew their ships, tied so closely to land operations, would be sitting ducks for enemy aerial assaults. They trusted that the invasion forces would speedily seize Japanese airfields already on Okinawa, thus freeing the Navy to depart.

Beginning March 26, a destroyer or a destroyer minesweeper manned each station. After the April 1 landings, as soon as they could be spared one or two LCI gunboats, LSMs (Land Ship Medium), or LCS (Littoral Combat Ship) craft joined the destroyers to provide added antiaircraft firepower. The ships lacked the punch offered by Laffey and other destroyers, however, causing the destroyer crews to label them the “Pallbearers,” a grisly reference to the lethal toll exacted at the picket stations and the lack of offensive power added by the landing craft.

No one aboard Laffey wanted to compare an exposed picket station to a Marine unit charging into enemy machine gun fire, but they and other naval personnel understood the risks. By being the first ships that the kamikazes encountered, they occupied the most treacherous sea posts near Okinawa, similar to a solitary cavalry scout sent into Indian territory so he could provide an early warning to the main unit miles behind. Men aboard destroyers grimly joked that they were the bait to entice the kamikazes, and that it was only a matter of time before they were hit. As one sailor aboard a picket destroyer said, “the waiting was scary too, knowing what was coming when those pilots’ one wish in the world was to kill you.”15

Inexperienced Japanese pilots traveling one of those sixteen routes to Okinawa often attacked the first vessel they spotted, instead of searching for a carrier or battleship. They also had read the words of Admiral Ugaki, who urged his pilots to take out the picket ships and their radar so that subsequent kamikaze pilots could go after larger prey. Picket destroyers thus absorbed a disproportionate amount of damage.

Becton, a veteran of Pacific action, wrote of picket duty that “every skipper at Okinawa dreaded the assignment,” not because of the dangers that came with it, “because danger was part of a destroyer’s job. But all destroyer men are imbued with a tradition of aggressive offense, and waiting for an enemy to come to them was not much to their liking.”16 He preferred to put the enemy on the defensive rather than granting them the initiative.

“That One Chilled Our Blood”

Destroyers on picket stations drew kamikazes toward them like a magnet attracts iron filings. Although most operations consisted of twenty or fewer aircraft, the Japanese mounted ten major offensives, the kikusui, in which anywhere from fifty to three hundred aircraft pounced on American ships. Some broke through the destroyer picket line and attacked the larger ships, but the American destroyer pickets bore the brunt of the assaults.

The first kikusui hit the American fleet on April 6. “Red Alert. Many enemy aircraft reported closing from the north,”17 blared Laffey’s public address system. None of the aircraft came within firing range of Laffey, then screening off Okinawa’s western coast, but Becton kept the crew at general quarters throughout the day in light of the numerous reports of bogies in the area.

In the afternoon fifty kamikazes swarmed Picket Station No. 1 and the adjoining Station No. 2. Although the CAP splashed the majority, some battled through to hit the USS Bush (DD-529) at Station No. 1 and the USS Colhoun (DD-801) at Station No. 2. Both ships sank later in the day. Kamikazes dived into targets off southern Okinawa, off the east coast, and even inside Kerama Retto, sinking three destroyers, one LST, and two ammunition ships, while damaging ten others and killing 367 men.

The attacks emphasized the dangers of operating near Okinawa. Laffey’s crew had witnessed kamikaze attacks off the Philippines, but as Becton wrote, “none of us had ever experienced attacks of such magnitude and intensity”18 as the ones that occurred on April 16. The longer they remained in Okinawa waters, the greater the likelihood that sooner or later, one or more kamikaze would target them.

Within twenty-four hours a threat from the sea grabbed their attention. Quartermaster Phoutrides was enjoying a few quiet moments belowdecks when the ship suddenly lurched forward and gained speed. Seconds later a call to general quarters sent him scrambling back to the bridge, where he observed a cluster of battleships and cruisers moving into the familiar circular cruising formation.

Reports had arrived that the world’s largest battleship, Japan’s mighty Yamato, and her escorting ships had left Japan’s Inland Sea with the probable intent of attacking American surface forces off Okinawa. Laffey had been ordered to take station on the right flank of a unit hastily formed to race north to meet the enemy force.

Phoutrides believed that they had enough firepower in the task force—six battleships, seven cruisers, and twenty-one destroyers—to crush Yamato and her nine deadly eighteen-inch guns, but others were not as optimistic. Screening off Okinawa seemed more alluring than going up against those heavy guns. “Now, that one chilled our blood,”19 wrote Lieutenant Manson of the expected fight against the most potent warship then afloat.

One hour after leaving, the task force changed from circular disposition to the rectangular battle formation, with Laffey’s division standing at the apex. “Our division was to go in first, and we were excited about that because we were finally on the offensive. Until now we had screened,”20 said Phoutrides.

Within hours Admiral Mitscher’s carrier aircraft intercepted the Japanese force and sent Yamato to the ocean’s bottom, ending the need for the American surface unit. At 10:00 p.m. Laffey and the other ships turned back to Okinawa to resume their stations.

“It was great to hear that the carrier aircraft had destroyed Yamato,”21 said Sonarman Zack, who believed the odds favored the Japanese should his ship go head-to-head with the enemy battleship. The charmed life of the USS Laffey continued.

“At That Point, It Was Pretty Routine”

A variety of activities occupied Laffey April 7–12, some mundane and others fraught with peril. “We have been shelling the beach for the past few nights,” Fireman Gauding wrote in his diary. “Using mostly star shells to aid our troops on the beach.”22 The crew became accustomed to the sound of general quarters, but unlike at Normandy, Phoutrides and his shipmates now hastened to their posts as veterans of war. The Normandy training ground had prepared them for Pacific duty.

Over the next four days they needed every bit of composure they could muster, as additional kamikazes buzzed the American fleet like angry wasps. They came singly or in pairs, rather than in the gigantic kikusui of April 6, but they exacted a disturbing toll, smashing into six warships in four days. Sailors kept close watch at dawn and dusk, when suicide pilots liked to attack from the rising or setting sun, and learned to be wary on moonlit nights when, as one sailor described it, kamikaze aircraft swooped down “like a giant bat gliding in.” Admiral Spruance, normally a man of few words, labeled the nighttime kamikaze pilots “witches on broomsticks.”23

While always cognizant of the kamikaze threat, Becton focused on other tasks during April’s first week and a half. The ship patrolled offshore, keeping watch seaward for suicide boats, which had already smashed into three ships, or swimmers with hand grenades attempting to sneak up on vessels. They engaged in shore bombardment, exploded mines off Okinawa’s east coast, and searched for possible launching sites for enemy suicide boats. On April 9 their supporting fire helped American ground forces in the Nago Wan area blunt an enemy counterattack backed by Japanese tanks, artillery, and mortars. They conducted nighttime harassing fire on the enemy in hopes of disrupting their rest.

Whenever an SFCP called in coordinates, Laffey’s five-inch gun crews blasted enemy troop concentrations and defenses, but they learned to be careful lest the Japanese trick them into firing on American units. “We were told the Japanese tried to cut in on our frequency and a soldier who spoke perfect English would act like a spotter and try to direct fire onto our own men,” said Phoutrides. “We’d have to verify that they were American by asking questions, such as his name and ship. You did this every time.”24

One morning the 40mm and 20mm crews joined the ship’s five-inch guns when a kamikaze approached on the formation’s port side with an American F4F Wildcat fighter in pursuit. They received credit for an assist when the plane crashed near the USS Idaho, (BB-42), but not before the plane had drawn uncomfortably close to the Laffey.

“The only time I got nervous was when we were tracking incoming bogies,” said Phoutrides “I’d listen to the reports and notice the range closing. Becton would say, ‘Commence firing,’ and there would be four to five seconds between his order and the first shot, and I was really nervous. I’d think, ‘What are you delaying for? That plane is getting closer!’”25

To some, those early April days off Okinawa proved less dangerous than prior Pacific operations. On April 8 Admiral Turner wrote Nimitz that it seemed the Japanese had slowed their operations off Okinawa. Others claimed the enemy had expended most of their kamikazes at Lingayen Gulf, and boasted that the seizure of airfields on Okinawa that could house Marine F4U Corsair fighters would prevent the Japanese from mounting a large-scale kamikaze attack. The kamikaze assaults that filled their days and kept them awake at nights in the Philippines were becoming distant memories.

“It seemed to be easier than before, easier than Iwo Jima,” said Lieutenant Youngquist. “At that point, I felt good about things. It was pretty routine before April 13.”26

Any hopes for continuing a quiet routine dissipated on April 12 with the second kikusui raid. Almost two hundred kamikazes, escorted by an equal number of fighters, fell on the fleet, with enough smashing through the CAP to damage the aircraft carriers, Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Essex (CV-9), four battleships, and more than twenty other ships. At Picket Station No. 1, kamikazes forced the destroyer USS Cassin Young (DD-793) to retire to Kerama Retto for repairs, smacked into the USS Purdy (DD-734), killing thirteen and wounding twenty-seven, damaged one landing craft, and sank a second. In one day at one station, the Japanese had eliminated four American warships from battle, and temporarily removed the ships that had to leave the line to escort the damaged vessels to repair facilities.

The Laffey crew counted their blessings. They had little about which to complain, other than the normal sailors’ gripes about food or overbearing chiefs. If they wanted to moan about their duty, they only had to look to the north, where Picket Station No. 1 had been turned into an oceanic bull’s-eye for kamikazes. The tasks might be boring where they were off Okinawa’s coast, but at least they were not posted to Picket Station No. 1. Those poor guys got it every day.

“This Is One I’d Rather Not Give You”

On Picket Duty No. One

We took up our spot

To report the movement of the Rising Sun

—“An Ode to the USS Laffey (DD-724),” Gunner’s Mate Owen Radder

Lieutenant Theodore Runk realized that as the ship’s communications officer he rarely enjoyed more than brief moments of solitude. He spent most of his hours in the coding room, overseeing the men who sent coded messages to Admiral Nimitz and other superior officers, and receiving similar items in return. Commander Becton, who believed that knowledge was a key component of being a good skipper, wanted to read every message sent to or from his squadron, even those relayed from one destroyer to another. This kept Runk and his men busy, but Runk never minded. The added workload made the hours pass more quickly. If a message arrived when he was away from his post, Lieutenant Youngquist or one of the enlisted men working in the coding room alerted Runk.

Laffey was screening for a battleship south of Naha the night of April 12–13 when near midnight a dispatch broke the monotony of routine ship messages. Runk read the note, but rather than handing it to an enlisted, he decided he should be the one to deliver this news to Becton. He climbed the ladder to the bridge and found Becton in his sea cabin.

“Captain, this is one I’d rather not give you,” said Runk. Becton, slightly surprised to see Runk standing before him, figured something important was up. He displayed no emotion as he read the message Runk handed over, and then replied, “Yes, Ted, I see what you mean.”

The order was the one each skipper commanding a destroyer off Okinawa preferred to avoid. After steaming to Kerama Retto to pick up a Fighter Director Officer (FIDO) team, Laffey was to turn north and travel to the most exposed spot of the sixteen picket stations that ringed Okinawa: Picket Station No. 1. “That meant only one thing,” wrote Becton. “Laffey was being assigned to a station on the radar picket line. The gates of hell awaited us.”27

Word of their new destination, which destroyer crews had labeled “Purple Heart Corner” and “Bogie Boulevard,” quickly spread about the ship that April 13. One of the men working near Phoutrides pointed out that it was now Friday the 13th, a fact that was certain to gain notice among sailors. When a second man urged those near him to add the three digits of the ship’s number, 7-2-4, Phoutrides mentally calculated the answer: 13. “Sailors are a superstitious lot,” said Phoutrides, “and we thought something was going to happen to us. It went through the ship like wildfire.”28 An assault that had begun on April Fool’s Day now included orders to Laffey to operate at Picket Station No. 1, arguably the most dangerous location then in the Pacific, on Friday the 13th.

Lieutenant Manson’s first thoughts were that the destroyer would stand directly in the flight path between Japan’s southernmost airfields in Kyushu and Okinawa, and that most of the destroyers sent to Picket Station No. 1 had either been sunk or damaged by kamikazes. He said that, “it wasn’t a question of whether it [Laffey] would get hit or not, it was just a question of when and with how many.”29

Torpedoman’s Mate 2/c John F. Schneider and his buddies discussed the possibility that they might not return alive from the station, and found that each man tried to convince the others that everyone would be fine. They assured one another that they would emerge unharmed, just as they had escaped unharmed off the Normandy beachhead, Cherbourg, the Philippines, and Iwo Jima. Luck had so far favored them, “and we thought that we might be able to break the jinx [of destroyers getting hit at Picket Station No. 1]. But we knew that just about everything that was sent out did get hit sooner or later.”30

Gunner’s Mate Delewski, who had done so much to prepare his gun crew for battle, understood the risks, but was confident his men would answer the challenge. “We were not blind and we were not stupid,” he said. “We knew where we were headed and what could happen. We knew we had to be at our best.”31

“That was the number one spot,” said Seaman Johnson. “We knew we’d eventually go up there. We’d seen those ships that came back, so we knew we’d be in real trouble. The rest of the operations we were on were not as dangerous, but we figured this was it, we’re probably going to get hit.”32

Whereas others dwelt upon the damage inflicted on destroyers, Sonarman Zack thought about the reason why Laffey had so far avoided harm. “Off the Philippines, Japan, and Iwo Jima we were always with a battle group, and you figure the bigger ships will be the target. But if you’re alone, you’re the target.”33

Kamikazes had selected the choicest vessels, the biggest ships, for destruction. In the Philippines some of the deck crew witnessed enemy aircraft drop into a dive directly toward them, only to change course and veer toward a cruiser or battleship. Where the Laffey was now going, Zack knew, they would be alone. They would be the biggest ship and the choicest target.

Becton overheard a steward’s mate boast, “nothing’s going to happen to us. Maybe to those other ships, but not to Laffey. We’re too lucky!”34 Becton remained silent, but doubted that their luck could hold out forever.

“They’ll Keep on Coming ’Til They Get You”

Under cloudy predawn skies, Laffey left her station off southern Okinawa and turned west toward Kerama Retto. Crew had heard the nickname, “Busted Bay,” which sailors bestowed on the anchorage for the numerous damaged warships that had limped into Kerama Retto, but until now it had meant little as the ship had avoided harm. They had observed some of the kamikaze-induced devastation during an April 6 visit to the anchorage, but no one—not Becton, Phoutrides, Gauding, or anyone—was prepared for the Dante-esque sights that greeted them as Laffey pulled into Kerama Retto.

“It was depressing as the devil and a little frightening, too,” wrote Becton as damaged ship after damaged ship came into view. “It went on and on until it felt you were moving down the aisle in the middle of a hospital ward full of mangled and crippled casualties.”35

Men on deck stared at the spectacle. “What a sight! What an awful sight!” recalled Lieutenant Manson. “Grotesque patterns of superstructures etched against the blue sky; mattresses and loaves of bread floating in the oil slicks oozing from torn hulls. All over the harbor colors were at half-mast, as damaged ships buried their dead.” Small boats hastened from one damaged ship to another, bringing physicians for injured men and repair crews for bent propellers and torn masts. Streams of wounded, many hideously burned, poured from battle-scarred warships to hospital ships as “Laffey’s sober-faced crew just looked, sadly shaking their heads.”36

“Going into Kerama Retto was awful,” said Sonarman Zack. “One cruiser had her bow blown off, and many destroyers were there that had been flattened by kamikazes. You [could] sure see the damage that one plane can do to a ship if it hit in the right spot.”37

The veterans aboard Laffey spotted destroyers on which they had earlier served, or ships bearing buddies from old times. The bow of one destroyer minelayer had been wrenched back across her bridge, and the muzzle of a five-inch gun was twisted into a right angle. Ships sported scorched decks, ruptured fuel tanks, and collapsed sides. The signal bridge of the battleship USS Tennessee (BB-43) had vanished from suicide crashes, and Japanese bullets and bomb fragments had punctured hundreds of holes in superstructures.

Crew manning Laffey’s 40mm or 20mm guns scrutinized similar locations aboard their damaged compatriots, now charred from bomb explosions and fires, grim foreshadows of what could happen to them. Lieutenant Matthew Darnell, the ship’s surgeon, stared at the demolished wardroom of one destroyer and muttered, “that’s my battle station.”38 On a destroyer that had once delivered mail to Laffey, a burial crew prepared bodies for the trip to the cemetery.

When Laffey pulled alongside Cassin Young to pick up a FIDO team consisting of Lieutenant E. L. Molpus, Lieutenant J. Vance Porlier, and three enlisted men, her skipper, Commander J. W. “Red” Ailes, whose ship had barely avoided sinking from kamikaze attacks at Picket Station No. 1, Laffey’s destination, said simply, “duck as fast as you can, make as much speed as you can, and shoot as fast as you can.” Members of Cassin Young’s crew shouted their own warnings to Laffey sailors. “You guys have a fighting chance, but they’ll keep on coming ’til they get you.”39

The Laffey crew had gained valuable experience since the ship’s commissioning, but the perils of Picket Station No. 1 presented a different scenario. They had never been ordered to occupy a static position and wait for the enemy to come to them. Becton and the crew hated being the bait, but they had their orders.

“You know what you are facing but you had no choice. It was our duty,” said Seaman Johnson. “You were part of the ship and the ship was ordered to go, so you went.” Quartermaster Phoutrides understood that the threat of a kamikaze attack always existed, “but it wasn’t until we got to Kerama Retto that I thought much about it. It was hard to believe when you saw those ships.” For the first time since he went to war he thought, “something might happen to us.” Gunner’s Mate Robert Karr said that “we all felt that our time of testing was at hand,” and Gunner’s Mate Delewski, added, “no one had to draw any pictures for us. No one had to say a word. We all knew we were in for the fight of our lives.”40

After filling Laffey’s magazines with three hundred rounds of five-inch ammunition, Becton took the destroyer to the command ship USS Eldorado (AGC-11) for final orders from Admiral Turner. Radio and radar technicians boarded to check the equipment, reminding Lieutenant Manson of a physician who inspected a boxer moments before he was to step into the ring.

Coxswain George Falotico had long wanted to leave his station inside Mount 52 for a more open post. Now, directly before leaving for the most dangerous sea station at Okinawa, he and Gunner’s Mate 3/c Stanley H. Ketron agreed to switch places. Ketron moved inside the mount and Falotico took his place on a 20mm gun. Falotico understood that he was now more exposed, but in his opinion that was a small price to pay for fresh air and an enhanced view of events.

“Our Turn Is Coming Up Tomorrow”

The bad news continued that Friday the 13th when an announcement over the public address system informed the crew that their president of the past twelve years, and their commander in chief, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, had succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage. The death of their leader, who loved to sail and had long held a special place in his heart for the Navy, hit hard because Roosevelt had been the only president many of them had known. After assuming office in 1933, he had guided the nation through the depths of the Depression, stood as a principal opponent to Adolf Hitler, proclaimed the country the “Arsenal of Democracy,” and oversaw the massive military build-up used to wage war in the European and Pacific theaters. Now, instead of the constant, ever optimistic Roosevelt at the helm, an unknown commodity would be in charge. Every ship and shore station was to conduct a memorial service on April 15.

Phoutrides had heard many of Roosevelt’s famous radio chats, and was saddened that the president would not be around to see the defeat of Japan and Germany, objectives that had dominated the last years of his presidency. Others, like Lieutenant Youngquist and Seaman Dockery, nudged the news aside. Something that occurred thousands of miles distant had little impact on their immediate futures, and besides, they had more important matters on their minds.

Tokyo took advantage to drop propaganda leaflets behind American lines on Okinawa, claiming that Roosevelt died because the strain of huge losses on the island was too much for him to bear. The leaflets promised more of the same, and warned, “the dreadful loss that led your late leader to death will make you orphans on the island. The Japanese special attack corps will sink your vessels to the last destroyer. You will witness it realized in the near future.”41

Better news followed with the unexpected delivery of bags of mail. Because they had been at sea for much of the past month, letters from loved ones had become a premium. With Picket Station No. 1 looming, Becton pulled every trick in his impressive bag to arrange a delivery before they left Kerama Retto for their post to the north.

Becton flashed a message to a nearby LST asking if they had any mail aboard. The LST replied that they did, but Laffey would have to wait her turn as the LST had been besieged with similar requests from other ships. Becton, about to take the crew to a post from which some might not return, and knowing how important even a few lines from mothers or wives might mean to his men, told a signalman to send the message, “Five gallons of ice cream for immediate delivery of any mail for the Laffey.”

Within moments came the reply, “Send boat!”42 Laffey’s boat crossed to the LST and returned with seven bags of mail. Sons grabbed letters from parents and husbands clutched photos of children they had not seen in months. The crew forgot, if only for a few hours, the specter of the coming days, and morale soared for men about to head to Picket Station No. 1. Becton devoured a letter from Imogen Carpenter, but it took every bit of wisdom he possessed to console the man who received a Dear John letter from his wife, who informed the sailor that she had sold their store back home and moved away with another man.

Becton’s thoughtfulness in arranging for the delivery, coming on the eve of their departure for the hottest naval spot around Okinawa, impressed everyone. “He got mail for us, which was a big deal for the crew,” said Quartermaster Phoutrides. He wrote his brother in June 1945, “we had been underway for about 7 weeks without getting any mail and the crew was pretty much in the dumps about it. On top of that, many of us had a premonition we were going to be hit, and when you feel that way, a measly letter sure helps out.” As he added almost seventy years later, “It shows how much he cared for the men.”43

Mail provided a welcome break from the chilling sights that dominated recent days. “Have just seen the graveyard for our ships that have been hit while on picket duty,” Fireman Gauding wrote on April 13. “Our turn is coming up tomorrow for picket duty. It sure looks like our turn is next. Every ship so far has gotten hit with a suicide plane. We have all got our fingers cross [sic] & hope for the best.”44