Chapter 6

* * *

TELEPATHY (late nineteenth century [origin from “tele-” + “-pathy”]): The communication or perception of thoughts, feelings, and so on by (apparently) extrasensory means.—Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “telepathy”

* * *

When people pray, they’re basically attempting to communicate with some sort of being, God or god, saint, angel, spirit, or ancestor. But that being, insofar as it exists, is not physically present and does not have a physical form with ears anyway, so from a materialist’s perspective, praying, aloud or silently, is a waste of breath and time. But what if mental intentions and information could be shown to travel across space to other living human minds?

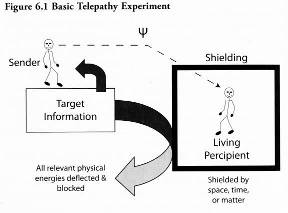

The basic idea of telepathy, a term coined by classics scholar and early psychologist Frederic W. H. Myers in 1882, is that one person’s mind can pick up information from another person’s mind. Figure 6.1 shows the basic procedure for a telepathy experiment. In an experiment, the target information is examined with the intention of mentally sending it by a sender or agent, so that we know that the relevant target information exists in the mind of the person acting as sender. This sender is materially isolated from the percipient, another living person who acts as the detector, by distance or material barriers. If total materialism is correct and there’s indeed no such thing as telepathy, then the sender’s attempts to mentally send the information will have no effect: the percipient’s calls will be nothing but guesses, and results will merely reflect chance variation. If there’s some kind of telepathic channel operating even intermittently, shown by the dotted line labeled ? (the Greek letter psi) in the figure, while there still may be lots of chance variation, it won’t be only chance variation; there will be extra hits in identifying the target information. (13)

Telepathy implies, of course, that mind is somehow of a different nature than matter. We set up the experiment so that, given our knowledge of physical matter and reasonable extensions of that knowledge, nothing could happen; yet in practice something sometimes happens.

In the classic days of parapsychology, card-guessing tests were standard procedure. The sender would usually be in a separate room, perhaps even in another building, to be sure there were no relevant sensory cues about the cards given off by the sender. The experimenter (who was sometimes also the sender) would thoroughly shuffle a deck of target cards, and at a designated time, the sender would begin looking at the cards one by one, in sequence. He would look at each card for a designated length of time, say half a minute, while trying to send the identity of that card to a distant percipient. Starting at the same time, the percipient, in another room, would try to get an impression of what the card was and either write it down or tell it to an experimenter, who wrote it down. After completion, the order of the deck of target cards would be compared to the percipient’s calls, hits would be counted, and a statistical evaluation made.

At this stage of our knowledge, we don’t actually know how much the sender’s efforts to send really matter. Many experiments formally designated as telepathy experiments might actually have their results due to clairvoyance or precognition, as described in following chapters. In spite of this lack of theoretical clarity, though, the idea of mind-to-mind communication, telepathy, is a commonsense idea that will undoubtedly stick with us. Its existence is especially important if we think that mind is of a different nature than body, resulting in some kind of dualism. Without getting into the theoretical complications, then, I’ll continue to use telepathy in the commonsense way to mean that the relevant target information exists in someone’s mind—who may or may not be actively trying to “send”—at the time the percipient is trying to get the information by some kind of psi perception.

Let me give you the flavor of a telepathy experiment by describing some of my own training in telepathic ability.

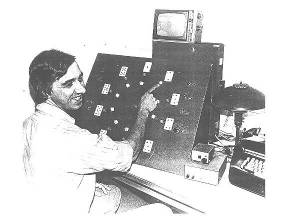

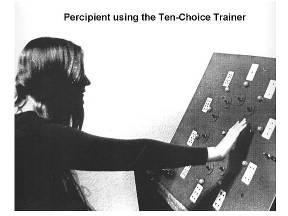

Figures 6.2 and 6.3 show the sender (a younger me, in this case) and a percipient or receiver (one of my students at UC Davis) in an extensive telepathy experiment I carried out in the 1970s (Tart 1976). Note that this was not an experiment designed to test the reality of telepathy per se, although it added to the evidence for the existence of telepathy. As I mentioned earlier, an enormous amount of evidence for the reality of phenomena like telepathy had been collected long before I came into the field. It’s always been clear to me that nonacceptance of that evidence was almost always for irrational reasons, so I never saw the point in collecting more proof-of-existence evidence that would also be irrationally ignored. The purpose of my experiment was to try to see if people could be trained to use telepathy more effectively by giving them immediate feedback on how they were doing. (14)

As a result of my conventional psychological training, I’d thought about the basic telepathy-testing situation in a different way than parapsychologists usually conceptualized it. They thought of it as testing how much telepathic ability a sender and percipient team had. I reframed it as a situation in which the percipients (and agents) needed to learn what to do, instead of just being a matter of testing the level of a talent they already possessed. After all, if someone says, “Lift your right hand while wiggling your fingers,” you can do that with ease and precision because you’ve long ago learned how to do that, but if the person says, “Read my mind,” what are you supposed to do? Concentrate hard? Relax? Pray for success? Take a casual attitude? Stare at the ceiling? Pray for aid from the local nature spirits? Breathe deeply? Breathe shallowly?

In the almost universal procedures used in telepathy experiments that had been done before I came into the field in the late 1950s, a percipient in a telepathy, clairvoyance, or precognition experiment guessed at the identity of an entire deck of cards before receiving any feedback as to whether any particular guess were right or wrong. From a psychological perspective, this struck me as what psychologists term an extinction paradigm, a procedure that kills off any talent a person actually has in a given task through confusion and discouragement. (15)

Figure 6.2 Charles Tart Sending with Ten-Choice Trainer

Think of it this way: In classic card-guessing tests, on any given trial, you have to make a call as to what you think the target card is, so you hope for inspiration or some kind of feeling to guide you, and when (or if) it comes, you act on it. Or perhaps you just “guess,” whatever internal psychological process “guess” means at a particular time. Then you have to make another call and another call and another call. By the end of a run through the cards, when the results of your calls through the target deck are scored and shown to you, you might find that you were right on, say, the third, seventh, fifteenth, sixteenth, nineteenth, and twenty-third trials. This is delayed feedback. Were those hits the ones on which you felt especially confident, or were those the ones on which your body seemed to tingle? Or, what else? That is, the feedback of rightness or wrongness comes too late for you to begin accurately discriminating what kind of internal cues or feelings might indicate that your call was actually influenced by psi perception, versus those on which you were just guessing. So my experiment was designed to test whether providing immediate feedback to percipients who already showed some talent at this kind of procedure, such as in a screening test, would enable them to gradually increase their scores, instead of their scores gradually diminishing to chance, resulting in extinction of talent, as was, sadly, the normative result for repeated guessing studies. The commonness of the decline effect, a falling off of scoring with repeated trials until it often reached chance, was frequently cited as strong evidence for the reality of psi ability. Chance, after all, doesn’t get “tired,” “bored,” or “confused”; it operates uniformly over time. People, though, get tired, bored, or confused.

In my procedure, the sender sat in front of a panel on which ten lights, each with a corresponding switch beside it, were arranged in a circle. An electronic random number generator (RNG) (the little box on the right, on top of a somewhat larger box in figure 6.2) was used to select which of the lights would be lit and thus serve as the telepathic target on any particular trial. (16) When this target was selected and the experimenter or sender turned on the chosen target light, a “ready” light in the center of the circle on the percipient’s panel (see figure 6.3), came on to show her that it was time to try to telepathically perceive what the correct target was and then indicate her response by pressing the appropriate button beside the light she thought was the target. Immediately, the correct target light came on, so the percipient got instant feedback on whether or not she was correct. (17) If incorrect, was she physically close to the correct target? If she was exactly correct, a pleasant chime also rang inside the apparatus. Percipients came to love the sound of that chime!

Figure 6.3 Student Percipient Using the Ten-Choice Trainer

These were large-scale experiments. Working with student coexperimenters I trained in my experimental psychology class at UC Davis, in the first study we screened more than fifteen hundred students for psi ability, giving a group psi test in their classes and inviting those whose individual results looked significant to a confirmation study to see if their results held up or were probably just chance variation. Those who continued to show high scores were invited to participate in the main training study, where ten completed at least twenty sessions on the ten-choice trainer, shown in figures 6.2 and 6.3 above, and fifteen completed at least twenty sessions on a commercially manufactured four-choice trainer by Aquarius Electronics.

The formal results of two training studies, reported in full elsewhere, were very promising. The first training study (Tart 1976) showed a probability of its total hits happening by chance of 2 x 10-25, two times ten to the minus 25th power—yes, that’s ten with twenty-five zeros after it, two in more than a million billion billion—on the ten-choice trainer and 4 x 10-4—four in ten thousand—on the four-choice trainer. No percipient showed a decline in scoring over time (the drop-off I theorized was extinction that was so typical of parapsychological studies), and some showed suggestive signs of getting better with the feedback training. The most significant percipient made 124 hits when only 50 were expected by chance.

A later, second study had to be done with less-talented percipients, due to a lack of enough assistance for the screening stages, and it ended up showing chance scoring on the ten-choice trainer, but significant scoring on the four-choice trainer.

All in all, I felt that a good case had been made that immediate-feedback training might improve telepathic ability, but I didn’t have the resources to keep following up on this line of research. Large-scale empirical studies would need to be done on how much initial psi talent was needed if learning were to overcome the inherent extinction of being right by chance, for instance. And which was the better test situation: ten-choice, four-choice, two-choice, or what? Fewer choices, for instance, meant the feedback bell showing you were correct would ring a lot, making you feel good, but most of those rings would be due to chance and thus add confusion. A many-choice test, on the other hand, would have very few false rewards due to chance, but a person might get discouraged in the long intervals between genuine psi hits.

What I and most of my coexperimenters found especially interesting was the apparent unconscious manifestation of psi ability. Time after time, as experimenter or sender, you’d turn on the randomly selected target so that the “ready” light came on in the middle of the percipient’s console and, via closed-circuit television, you’d see the percipient immediately reach up and stop his hand right over the correct target. You’d immediately begin “mentally shouting” (no actual sounds were allowed, of course), “Push it, push it, push that button! You’re right!” only to watch the percipient move his hand away to other targets, come back and hover over the correct target again and again, and then finally move his hand suddenly and push the wrong button!

All of us senders had fantasies about being able to administer electric shocks then! This would’ve been unethical under the social contract we had with our experimental percipients, but it was perfectly obvious that the percipient (or at least the percipient’s hand) knew the correct target; how could he go and push the wrong button?

This perception that the hand “knew” could’ve sometimes been selective misperception on our part as senders, of course, and I tried to get grant support to do further studies where all the percipients’ hand motions would be videotaped and later judged by independent raters to see if they really did “know” the target at some unconscious level. I wanted to take various bodily measures, such as galvanic skin response (the body’s natural response to perceiving a new stimulus), to further see if their bodies showed more activation over correct targets, further indicating that they’d “received” the psi message at some unconscious, bodily level that just hadn’t made it to consciousness. I never could get the funding to do this. (18) But this personal experience, plus a lot of other kinds of colleagues’ parapsychological experiments, strongly suggests that we can unconsciously “use” psi abilities. The use they’re put to may not be what we would consciously do. (We’ll look at this possibility later when we discuss psi-mediated instrumental responses.)

As I hinted at the beginning of this chapter, telepathy in some form might be the “mechanism” involved in prayer, the nonphysical way of conveying intention and information from your mind to another (kind of) mind. Since, in my judgment, the experimental parapsychological evidence for telepathy, plus people’s spontaneous experiences, shows that telepathy is a reality, it provides scientific support for engaging in prayer.

And insofar as a psi ability like telepathy may be used unconsciously—for example, the hands seemed to know, but the percipient’s conscious mind didn’t—the picture of what prayer might consist of or do gets complex. Might part of you, outside of your ordinary consciousness, be “praying for” things you don’t know about—more or less effectively? It’s an interesting, and somewhat scary, thing to reflect on.

While followers of scientism usually dismiss the evidence for the reality of telepathy a priori, without bothering to look at it since they know it’s impossible, some investigators have tried to explain it within a materialistic framework.

Our brains are made of physical matter and have known physical energies—chemical and electrical—coursing within them. With German psychiatrist Hans Berger’s 1924 discovery of electrical currents in the brain, some scientists immediately theorized that these electrical currents might also generate radio waves, thus making the brain a radio transmitter. If another brain could act as a radio receiver, we could have communication at a distance without the use of the usual physical senses: telepathy. The idea was very appealing: you took an exotic mystery, telepathy, and explained it “away” in terms of known scientific, physical knowledge. Insofar as this theory of telepathy is true, we should someday be able to build electronic devices that could both send and receive telepathic messages to and from human brains.

As you get more specific, though, telepathy as mental radio turns out to be a theory that doesn’t account well for the facts; indeed, the empirical facts contradict it. This was clear to me when I first became interested in parapsychology, because I’d been a ham radio operator as a teenager and then studied enough electronics to pass the federal examinations to receive a first-class radiotelephone license, allowing me to work my way through college as a transmitter engineer in various radio stations. Sending and receiving by radio were very familiar matters to me.

The first problem with the telepathy-as-mental-radio theory is that communicating by radio takes enough electrical power to send a signal over the required distance. While there can be interactions with external conditions (such as the state of the electrically charged ionosphere reflecting radio waves), generally the farther you want to communicate, the stronger the radio signal you need to generate. Signal strength falls off with the square of the distance. Looking at the kind of electrical power likely to be generated in the brain, it might be feasible to transmit for a few hundred feet, but the power required to communicate over thousands of miles—some telepathy tests have been successful at that kind of distance—would be well beyond what we could expect any material brain to generate.

The second problem is that the generation of such radio waves by the brain should be easily detectable by appropriate physical instruments placed near a sender’s head. For communicating over thousands of miles, the signal should be so powerful that such an insensitive detector as a fluorescent tube held near the sender’s head should light up; it does not. No instrument placed near senders’ heads has ever reliably detected radio waves carrying telepathic information, even of a low power.

The third problem is what engineers call signal-to-noise ratio. If you’re in a very quiet room, you can hear someone whisper to you across the room. That’s a high enough signal-to-noise ratio. If you’re in a noisy room though, like at a cocktail party, you can hardly tell that the person’s speaking, much less make out what’s being said; that’s a low signal-to-noise ratio. There has always been some electronic noise around anywhere on our planet due to electrical storms, but today the radio spectrum is saturated with noise from innumerable electronic devices. It’s possible to pick up electrical or magnetic signals from a brain, but it not only requires our most sensitive detectors, since the electrical or magnetic radiation is so weak, it also requires that the person be in an extremely expensive metal-shielded room to keep out all this extraneous radio noise. So for telepathy as mental radio to make sense in terms of what we know about the physical world, the brain would have to generate a strong signal that should be easily detectable but never has been detected, and this signal would need to be much stronger than the extensive ambient electronic noise on our planet to convey useful information.

The fourth problem is shielding. If telepathy is indeed some kind of radio transmission, we should be able to block telepathy by putting the sender, receiver, or both in electrically shielded rooms. But the occasional use of such rooms hasn’t knocked out telepathy results. Indeed, there’s some evidence (Tart 1988a) that working in electrically shielded rooms that are configured in a certain way may actually make telepathy stronger, although we need much more research to solidify and refine this data. This makes no sense in terms of conventional physics. My best guess at present is that the electrical shielding may cut down interference with brain functioning from electromagnetic sources, thus producing less distraction or interference from nontelepathy tasks, allowing a sender or receiver to function more efficiently. So the shielding doesn’t directly affect the telepathy; it’s simply putting the human instrument who expresses telepathy, the sender or receiver, in a better physical environment and thus mental frame of mind to use this nonphysical function.

Thus what empirical data we have to date about telepathy (and other forms of psi ability) is that it’s not affected by material distance or shielding. If telepathy were some form of radio communication, it would be thus affected. In this practical sense, telepathy (and other forms of psi ability) are nonphysical in nature, because they don’t show the lawful characteristics associated with relevant material phenomena.

Now note carefully that I use the adjective “nonphysical” in a strictly pragmatic way. I’m not making any absolute statement about the ultimate nature of reality. How would I know? And I usually qualify “nonphysical” with the phrase “given what we know about reality and reasonable extensions of that knowledge.” So what I’m saying more precisely and practically is this:

1. Given what we know about the ordinary physical universe, telepathy (and psi ability in general) doesn’t follow known physical laws or reasonable extensions of those laws.

2. Telepathy (and psi ability in general) often seems to “violate” those laws.

3. The practical meaning of this lack of sense in terms of conventional physics is that it’s probably a waste of time to sit around and wait for an explanation of psi phenomena and spirituality in terms of known physical laws, or reasonable extensions of known physical laws. Rather, we should investigate them on their own terms. Certainly, we shouldn’t ignore them or actively deny their reality!

How about the reasonable extensions of known physical laws? How far does “reasonable” reach?

Among some people there’s certainly a hard-core adherence to materialism that insists that everything will eventually be explainable in terms of current and yet-to-be-discovered physical laws (such as quantum effects). So we can ignore psi phenomena and spirituality, and wait until progress in physics handles them?

This is certainly an attitude that people can take, but it’s not science. Philosophers call this attitude promissory materialism, and it’s not science, because it’s not falsifiable: you can’t prove that it might not be true. I could just as well claim that these phenomena will all be explained one day in terms of little green angels with four arms who mischievously avoid all our attempts to see if they’re real. I guess we’d call that promissory angelism. In neither case can you prove that it won’t be that way at some future time, since the future never arrives.

If you know basic physics, you’ll know I’ve been talking about how telepathy is nonphysical from the perspective of a classical, Newtonian, commonsense universe. But what about quantum effects? What about the entanglement of two particles speeding away from each other at the speed of light and how a change in one produces an instantaneous change in the other?

The quantum picture of the universe is indeed very interesting, and some contemporary writers have cited aspects of it as science’s somehow justifying psychic and spiritual phenomena. Well maybe, and maybe not.

First, I’m skeptical of how well most of these writers actually understand quantum physics. I know enough physics to know that I don’t really understand quantum physics, so I won’t use my poor and possibly distorted understanding to argue for the existence of psi phenomena and spiritual phenomena. The existence of psi phenomena is more than adequately demonstrated by the empirical results of so many experiments already. I understand that this isn’t enough for some people. They want to have a good reason, a good theory, to accept something, but as I’ve said in outlining essential science in earlier chapters, empirical evidence, data, always has priority. It’s nice to have a theory to make you mentally comfortable with the data, but you can’t ignore or reject data simply because you’re intellectually uncomfortable.

Secondly, for all the intellectual fashionableness and excitement of quantum-theory approaches, they haven’t resulted in any better psi manifestations. I have a very practical approach to essential science: usually a better theory makes things work better. If you really understand something better, you should be able to work with it more effectively. Earlier I used the example that the germ theory of disease, implying that you’d better purify the water, worked enormously better than the demon theory of plagues, which led to ringing the church bells loudly to scare off the demons. I have brilliant colleagues who are involved in thinking about psi phenomena in quantum-theory terms, but I’m required by intellectual honesty to remind them occasionally that their quantum approaches don’t yield any more psi phenomena in experiments than approaches of any other sort.

I wish all theorists well, but all theories have to produce empirically verifiable results. Maybe quantum theory approaches will provide a useful theory of psi phenomena and spirituality, or maybe it’ll turn out to be a fashionable but passing distraction, the way the mental-radio theory of telepathy was. And just to complicate life, it seems to be generally true that when you believe you understand something, you act more confidently and effectively because of that confidence, regardless of the literal truthfulness of your beliefs. So thinking that quantum theory justifies the reality of psi phenomena, for example, may make you a more effective psychic, just as, to use a historical example, believing in the reality of helping spirits probably made people in an earlier time more effective at using their own psi abilities.

For those who want to follow up on this, the best starting point, with great relevance to spirituality, is Dean Radin’s book Entangled Minds: Extrasensory Experiences in a Quantum Reality (Paraview Pocket Books, 2006).