Chapter 7

Clairvoyance, or Remote Viewing

* * *

CLAIRVOYANCE (mid-nineteenth century [origin: French, formed as “clairvoyant”]: The supposed faculty of perceiving, as if by seeing, what is happening or exists out of sight. —Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “clairvoyance”

* * *

Reporting on his experience of Cosmic Consciousness (see the introduction), Bucke noted: “…Among other things he did not come to believe, he saw and knew [italics mine] that the Cosmos is not dead matter but a living Presence, that the soul of man is immortal, that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure, all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of everyone is, in the long run, absolutely certain” (1961, 8).

The classic materialist’s view is of a universe of separate objects, occasionally and meaninglessly affecting each other through material forces but basically dead matter, not linked together by some kind of living “presence.” Bucke had to be deluded when he wrote the above. But are things more linked than we normally imagine?

Clairvoyance, from French words meaning “clear (clair) seeing (voyance),” is the direct perception of the state of the physical world without the use of your normal physical senses or the intermediation of another mind. That is, at the time of a clairvoyance test, no one, no human mind, knows what the relevant target information is, so any positive results can’t be attributed to telepathy at that time. (19)

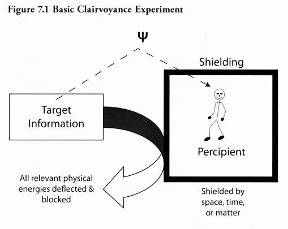

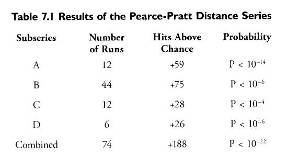

Figure 7.1 diagrams the basic clairvoyance-experiment procedure. This figure is almost the same as a telepathy procedure, but there’s no sender or agent involved. In classical parapsychological research, to conduct a clairvoyance test an experimenter would typically take a deck of cards and, without looking at the card faces, shuffle them thoroughly to randomize their order; put the deck back in its box, still without looking at the card faces; and often further shield the target deck by putting the box into a locked desk drawer. Then the percipient would be invited into the room and, while the experimenter observed her, asked to write down the order of the deck of target cards. (There are many variations of these procedures, of course, but they need not concern us here.)

Let’s look at a classic and outstanding clairvoyance study, the Pearce-Pratt experiment in clairvoyant card guessing, done at Duke University in 1933 and 1934. Hubert E. Pearce Jr. was a divinity student who had introduced himself to J. B. Rhine as someone who thought he’d inherited his mother’s clairvoyant abilities, and he’d already scored exceptionally well in previous tests. J. Gaither Pratt, later a leading researcher in parapsychology, was a graduate student in psychology at Duke and a research assistant to Rhine, although he hadn’t shown a particular interest in parapsychology at the time. J. B. Rhine, later founder and head of the Duke Parapsychology Laboratory, was then an assistant professor in the psychology department. Here’s Rhine’s description of the procedure (Rhine and Pratt 1954, 165–77):

At the time agreed upon, Pearce visited Pratt in his research room on the top floor of what is now the Social Science Building on the main Duke campus. The two men synchronized their watches and set an exact time for starting the test, allowing enough time for Pearce to cross the quadrangle to the Duke Library, where he occupied a cubicle in the stacks at the back of the building. From his window, Pratt could see Pearce enter the library.

Pratt then selected a pack of ESP cards [the Zener cards shown earlier in figure 5.2] from several packs always available in the room. He gave this pack of cards a number of dovetail shuffles and a final cut, keeping them facedown throughout. He then placed the pack on the right-hand side of the table at which he was sitting. In the center of the table was a closed book on which it had been agreed with Pearce that the card for each trial would be placed. At the minute set for starting the test, Pratt lifted the top card from the inverted deck, placed it facedown on the book, and allowed it to remain there for approximately a full minute. At the beginning of the next minute, this card was picked up with the left hand and laid, still facedown, on the left-hand side of the table, while with the right hand, Pratt picked up the next card and put it on the book. At the end of the second minute, this card was placed on top of the one on the left, and the next one was put on the book. In this way, at the rate of one card per minute, the entire pack of twenty-five cards went through the process of being isolated, one card at a time, on the book in the center of the table, where it was the target or stimulus object for that ESP trial.

In his cubicle in the library, Pearce attempted to identify the target cards, minute by minute, and recorded his responses in pencil. At the end of the run, there was, on most test days, a rest period of five minutes before a second run followed in exactly the same way. Pearce made a duplicate of his call record, signed one copy, and sealed it in an envelope for Rhine. The two sealed records were delivered personally to Rhine, most of the time before Pratt and Pearce compared their records and scored the number of successes. On a few occasions when Pratt and Pearce met and compared their unsealed duplicates before both of them had delivered their sealed records to Rhine, the data could not have been changed without collusion, as Pratt kept the results from the unsealed records, and any discrepancy between them and Rhine’s results would have been noticed. In subseries D, Rhine was on hand to receive the duplicates as the two other men met immediately after each session for the checkup.

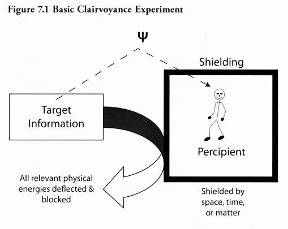

How did the Pearce-Pratt experiment work out? Table 7.1 shows the results for the four subsets (where conditions varied, with approximate distances from cards to Pearce of either 100 yards or 250 yards, and Rhine being more directly involved in subseries D, as well as for the total experiment).

Note again that Pearce had been preselected from earlier work as a very talented percipient: these aren’t the typical results one gets from unselected college students. He carried out a total of 1,850 calls in the combined study, scoring 558 hits when 370 were expected by chance, an average 30 percent hit rate instead of the 20 percent expected by chance with the five-choice Zener cards.

Note that these are extraordinarily significant results in terms of the odds against their being due to chance. Odds of 1 in 20 (.05) are usually called “significant” in psychology and many other branches of science, while odds of 1 in 100 (.01 or 10-2) are definitively significant. Odds like 10-4 (1 in 10,000) are seldom reached in ordinary psychology experiments.

Since the 1970s the most interesting form of clairvoyance experiments have been what’s called remote viewing (RV), a term coined by physicists Russell Targ and Harold Puthoff (1974) when they worked as researchers at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), a prestigious, private think tank that carried out a wide variety of contract research for the government and industry. (20) They chose the term “remote viewing” to make their research more understandable to mainstream scientists (the more general term, “remote sensing,” was in wide use in the scientific and engineering communities then, to refer to all sorts of instrumental ways to detect and measure things at a distance, techniques such as radar or echolocation) and to avoid the negative “mystical” connotations many people associate with a word like “clairvoyance.” I had the good fortune to be a consultant on some of these studies and see a lot of RV in action.

Puthoff and Targ once gave a report on their early RV studies at a small evening meeting of parapsychologists at my home in the San Francisco Bay Area. We were all somewhat amazed—and somewhat skeptical too—at the high quality and quantity of psi results their studies seemed to show. Most parapsychological studies yield statistically significant, but practically tiny, results. Puthoff and Targ were used to skepticism, however, and had already decided to actually conduct an informal RV demonstration at our meeting as the best way of dealing with our skepticism. One colleague left and randomly went to we knew not where. Half an hour later, we were asked to try to clairvoyantly see, or remote view, the target location where this person was, and make any notes or sketches we wanted to regarding it. Note that while this colleague was at the remote target location, we weren’t asked to try to get what he was thinking but rather to describe the physical locale, an emphasis on clairvoyance, not telepathy, although telepathy isn’t excluded. We’ll see later how in formal RV experiments, telepathy’s largely irrelevant to the results.

I had some interesting imagery come to me that involved some sort of factory or machinery, rotating drums or something, and bright colors. I wasn’t impressed though; it seemed rather vague to me.

Then we were taken to the target for feedback, which turned out to be a brightly lit launderette on University Avenue in Berkeley. I wandered up and down the sidewalk a little, looking at the exterior and plate-glass window of the launderette and thinking it didn’t very well match my remembered imagery that I had thought of as a factory. “Okay,” I thought resignedly to myself, “ESP doesn’t work really well very often; it certainly didn’t seem to work for me.” But then as I stood in a new position to the right side of the window and looked in, I suddenly saw an excellent fit with my imagery: the rotating washers and dryers looked much like the rotating drums I’d seen, and bright-colored clothes were in baskets on a table. I was impressed!

But this was just an informal demonstration of procedure, nice if you experience it personally but otherwise too subjective to count very strongly as evidence for clairvoyance, so let’s look at how formal RV experiments are conducted.

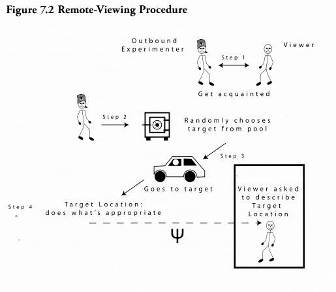

Figure 7.2 shows the basic procedure in the initial SRI (and many subsequent) RV studies. As a first step, a person I’ve sometimes thought of as the “hider,” or, more formally, the beacon person or outbound experimenter, meets and gets acquainted with the person who’ll serve as remote viewer. The beacon person will later go to some remote location, hidden from the ordinary senses of the viewer. At this point, though, the beacon person has no idea where he’ll go, so he needn’t worry about his interaction giving any cues to the viewer: there’s no information to give.

Figure 7.2 Remote-Viewing Procedure

In the second step, the outbound experimenter leaves and goes to another laboratory room, where he uses an RNG to decide which of about fifty envelopes he’ll remove from a locked safe. Each envelope contains the name of a target location that has visually interesting characteristics and is within a thirty-minute drive of SRI in Menlo Park, California, where the original RV research was carried out. Within a thirty-minute drive was a maximum time, but the target location could be mere minutes away, requiring the beacon person to use up a lot of time going around in circles driving to it. Given the richness of the San Francisco Bay Area, this meant that the target location could be almost anywhere; there were hundreds of thousands of sites to choose from.

At the end of the third step of traveling to the target, thirty minutes later, the outbound experimenter arrives at the target location and just hangs around in it, or does what’s appropriate for people in that location, the fourth step. If the target was a fast-food restaurant, for example, the outbound experimenter would order and eat there, or if it was a playground he’d swing on the swings.

At the thirty-minute mark, the remote viewer, who has stayed in a locked laboratory with an inbound experimenter, is asked to describe what the target location is like where the outbound experimenter is. The viewer speaks into a tape recorder and, typically, makes a number of sketches of her impressions.

But “Wait,” you might be thinking, “isn’t this a telepathy experiment rather than a clairvoyance experiment? Couldn’t the viewer be reading the mind of the outbound experimenter rather than directly perceiving the physical characteristics of the target location?”

Yes, the viewer could do that, but it wouldn’t really help her score well, and might even lower her score, as you’ll see when I describe the evaluation procedure. Sometimes the aspect of the target locale that was well described by the remote viewer was one that hadn’t even been visible to the beacon person at the time. And it was later discovered that you didn’t actually need an outbound experimenter at a target site for RV to work well anyway; this beacon person was usually a kind of psychological aid that wasn’t always necessary.

There’s a set period for the outbound experimenter to remain at the target, typically fifteen minutes to half an hour, and then he returns to the laboratory. The viewer’s recorded verbal descriptions and sketches have meanwhile been collected by the inbound experimenter back at the lab and locked away for later formal evaluation.

Now the outbound experimenter, the viewer, and the inbound experimenter all drive to the chosen target location so the viewer can make a direct, personal comparison of her impressions with what’s actually there. This comparison isn’t included in the material later given to a judge for formal evaluation, since it’s information gathered after the viewer knows what the target is by ordinary sensory contact while being there, but I believe this relatively fast (but not immediate) feedback to the viewer helps her hone her clairvoyant skills in the long run, learning to give more emphasis to certain kinds of feelings and impressions and less to others.

Although the results need formal evaluation, as will be described below, RV sometimes gives immediately striking results.

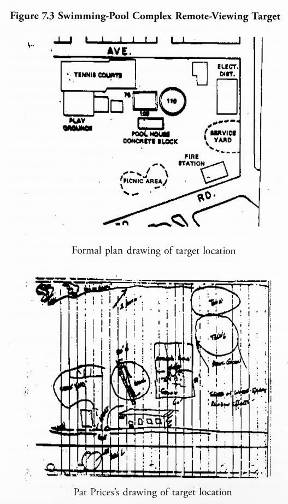

Figure 7.3, for example, shows a sketch (on lined paper) of an outstanding remote viewer, Pat Price, a retired police commissioner, made while remote viewing a target that turned out to be a public swimming-pool complex in Palo Alto, about ten minutes away from the laboratory. There’s a formal plan drawing made later for illustrative purposes above it (again, the plan drawing was not part of the formal evaluation, in case there was any bias in creating the drawing).

In Mind-Reach: Scientists Look at Psychic Ability, Targ and Puthoff (1977, 52–54) report:

…Pat’s drawing is shown…in which he correctly described a park-like area containing two pools of water: one rectangular, 60 x 89 feet (actual dimensions 75 x 100 feet); the other circular, diameter 120 feet (actual diameter 110 feet). He was incorrect, however, in saying the facility was used for water filtration rather than swimming. With further experimentation, we began to realize that the occurrence of essentially correct descriptions of basic elements and patterns coupled with incomplete or erroneous analysis of function was to be a continuing thread throughout the remote-viewing work.

As can be seen from his drawing, Pat also included some elements, such as the tanks shown in the upper right, which were not present at the target site. The left-right reversal of elements—often observed in paranormal perception experiments—is likewise apparent.

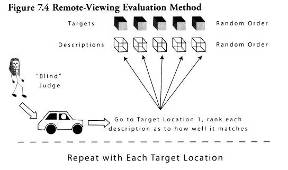

To properly and formally evaluate RV studies, you follow the procedure shown in figure 7.4. Basically, you do a series of independent RVs with different targets. Practically and mathematically, six is the minimum number of viewings you can have in an experimental series for the statistics to be adequate, while more than nine or so gets rather complex for a judge to keep everything in mind.

Let’s say you’ve done six RVs in separate sessions. The materials from each—drawings and a typed transcription of the viewer’s impressions—are put in six separate packets and arbitrarily labeled A through F. There’s no information in each packet as to what target location the descriptions were intended to go with. The swimming-pool complex material, for example, namely the transcript and Pat Price’s drawing (not the plan drawing shown above) would contain no information that this was supposed to be about the swimming-pool complex. Copies of the driving instructions to each of the six target locations used are also arbitrarily numbered 1 to 6. The twelve packets are given to a judge who doesn’t know what descriptions were supposed to go with what targets, a blind judge, to use the technical term. The judge is asked to drive to each of the target locations, read all six descriptive transcripts and drawing packets while at each location, and rank each description’s similarity to each target. So at target location 3, for example, the judge might decide that description F fits it best, then description B next best, and so on.

Now we can see how this kind of RV is primarily a clairvoyance experiment: the remote viewer must describe physical features of the target locations that the blind judge will later be able to notice. Passing thoughts in the outbound experimenter’s mind or idiosyncratic ways of perceiving physical reality won’t be of any use, because the judge has no idea what they were. Telepathy isn’t ruled out; an outbound experimenter could be looking at the target location from exactly the same vantage point the judge will later have and seeing it the same way the judge is likely to see it, but telepathy from the outbound experimenter to the viewer isn’t needed; clairvoyance will do. Again, it’s also important to note that while the early RV experiments used beacon people, with an assumption that this would make the procedure more interesting or more successful for the viewers, many later but just as successful RV studies had no beacon people involved at all. (21)

The technically inclined reader can look up the exact statistical methods used (Tart, Puthoff, and Targ 1979), but basically the formal evaluation goes like this. If there’s no clairvoyance involved, the viewer’s impressions are simply guesses, and they’re random and general. Some of them, especially broad generalities—“This is a big area”—will be correct, but they’re just as likely to be correct for the locations that were not the target for a given viewing as for the designated target, thus giving high “hit” scores to the wrong places. If the guesses are correct and very specific, on the other hand, they’re not likely to match any particular target location by chance alone. So to show a high likelihood of the involvement of genuine clairvoyance, the viewer must come up with specific items of description that are correct for the designated target but not for the other targets in the experiment, and that’s what the statistics formally evaluate. It’s important that the target locations used be clearly different from one another. A fast-food restaurant, a church, a playground, a fire station, a drive-in movie theater, and a redwood grove would be a good set, for instance, while six churches would have so much in common that it would take extraordinarily good RV to differentiate them enough for a blind judge to make correct matches.

To illustrate, in our example above, Pat Price gave some specifics—two pools of water, their approximate dimensions, and their shapes—that didn’t match elements in the other targets in that series. So the judge easily ranked that description as the best match for that target.

The fact that the judge is blind to which descriptions were supposed to go with which targets also controls for any biases on the judge’s part. A too-credulous judge will see correspondences everywhere; a too-skeptical judge will seldom see them anywhere, but a judge’s credulity or skepticism won’t systematically bias the evaluation of the results, except perhaps to make them less sensitive to detect genuine clairvoyance.

Although it was classified knowledge through most of the early work, it’s now well known that most RV research, especially that at SRI, was sponsored by various government agencies like the Department of Defense, the Army, or the Central Intelligence Agency, whose interests were primarily whether RV could be a useful form of supplemental intelligence gathering in the Cold War.

To become a consultant on the SRI project, I had to obtain a Top Secret security clearance and sign two contracts where I agreed not to reveal what the research found. I remember those contracts well, as agreeing to secrecy of any sort was not my usual style of life! But I believed this research was important for national security: wars tend not to start when the aggressive side believes the other side knows what its plans are. One contract stipulated the penalties for revealing secrets, namely ten years in prison and a ten-thousand-dollar fine. The other contract, which I humorously thought of as the cheap-secrets one, stipulated five years in prison and a five-thousand-dollar fine.

Fortunately for scientific knowledge, much of what was in these classified RV programs has been revealed by various authors (Schnabel 1997), who discovered them from documents recovered through use of the Freedom of Information Act, so they’re no longer secrets that I have to worry about revealing. However, a good number of the most successful results used in actual intelligence operations have never been declassified.

Amusingly, the results of classified military programs aren’t always what’s anticipated. My colleague physicist Russell Targ, for example, one of the pioneer investigators of RV at SRI, sometimes jokes that what he found while acting as a spy for the CIA led him to find God.

Support for RV research and its practical applications for the military and intelligence agencies eventually ended when it became well known enough to be politically embarrassing. As Russell Targ (2008, 147) put it, “Shortly after that (2005), the program was declassified, and Robert Gates, now Secretary of Defense but then a CIA director, announced on the TV program Nightline that the CIA had indeed supported the SRI program since 1972, but he declared that nothing useful ever came out of it. I wondered at the time why the interviewer, Ted Koppel, didn’t ask him why he supported such a stupid program for twenty-three years if indeed ‘nothing useful ever came out of it.’”

As with telepathy, discussed in the previous chapter, clairvoyance, as we currently know it, is nonphysical from the perspective of a classical, Newtonian universe.

Attempts to create a physical theory of clairvoyance began with the early card-guessing test results. If such tests are done with a percipient trying to guess a single card that has been removed from the shuffled deck and is facedown on the table in front of her, the physical analogy that comes to mind is that it might be some kind of “X-ray vision,” like that which Superman used in the comic books. Literal X-rays wouldn’t seem feasible, because the level of radiation involved would probably give the experimenters cancer soon, but perhaps some similar form of unknown, but definitely physical, radiation accounted for clairvoyance?

But many clairvoyance tasks with cards involved leaving the shuffled pack whole, as well as often putting it back in its box, putting it in some other kind of container like a desk drawer, or both. So some kind of X-ray vision gets much tougher to imagine. If you’ve ever tried to look through (using ordinary light rays rather than X-rays) a stack of slides, you’ve seen that all the images are jumbled together so that you can’t discriminate them.

Also, like telepathy, there’s no indication that ordinary physical-shielding factors like distance or solid barriers have any effect on clairvoyance scores, except psychologically. But if a percipient believes a kind of barrier will create a problem, it may.

In the model of clairvoyance given in figure 7.1, the target is “shielded” from the percipient. Usually these are fairly ordinary kinds of shields, ranging from the thickness of the cardboard a target card is printed on at a bare minimum to having the target cards stacked together to shield each other while being in a cardboard box that’s in a drawer and perhaps in another room with a wall between. There’s one kind of known classical physical energy that could penetrate such shielding, though—although how it could “couple” to the targets to pick up the information is a mind boggler—and that is extremely low-frequency electromagnetic radiation (ELF). Eliminating ELF as a possible carrier of clairvoyant information was the outcome of a unique, albeit one-shot, experiment, Project Deep Quest. (I find it wryly amusing that we have to worry about the action of an ELF in a parapsychology experiment, but I suppose it’s just a manifestation of my “elfish” sense of humor.)

Stephan Schwartz has been one of the most successful and creative investigators of RV, and was interested in the question of whether ELF might be important in RV. Through his contacts in the Navy (he had worked on many government projects in the past), in 1977 he was able to borrow the use of a deep-diving research submarine, the Taurus, which was doing its sea trials off Santa Catalina Island, near Los Angeles. Working with Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ to create target materials, Stephan and the Taurus crew took mutual friend and remote viewer Hella Hammid, an artist and photographer, more than five-hundred feet below the surface, below where it had been established that ELF waves could penetrate. This is the most thorough kind of shielding against any kind of electromagnetic radiation that you can get on our planet.

Although on the verge of nausea—it had been a rough voyage getting out to the dive site—Hammid’s RV impressions were (Schwartz 2007, 58): “A very tall looming object. A very, very huge, tall tree…a cliff behind them…Hal is playing in the tree. Not very scientific.”

Six sealed envelopes were then opened, one containing a photo of the correct target site (not known to anyone in the submarine), five being nontarget sites. Hammid selected the one of a large tree on the edge of a cliff, which turned out to be correct.

Later, well-known psychic and artist Ingo Swann, who’s credited with creating the idea of RV in the first place, was taken out, and dived to more than 250 feet. He remotely viewed that Targ and Puthoff were then walking about in a large, enclosed space, perhaps a city hall—but no, a mall, with reddish, flat-stone flooring. It turned out that they were strolling about in a shopping mall in Palo Alto (Schwartz 2007, 61).

ELF was out. Whatever way clairvoyance works, it’s very unlikely that it has anything to do with electromagnetic radiation. Applied in a rigorous way, the RV approach has yielded many interesting results. But note that a number of people have made questionable claims of being experts in RV, and offer to teach it to people for a high price. Caution is advised!