Chapter 9

* * *

PSYCHOKINESIS (English, twentieth century [origin: from “psycho-“ + “kinesis”]): The supposed ability to affect or move physical objects by mental effort alone.—Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “psychokinesis”

* * *

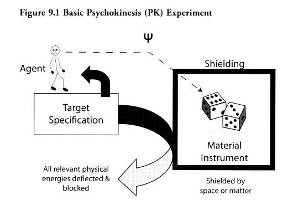

Psychokinesis (PK), or to use an older term, telekinesis, is the ability of mental intentions to directly cause physical effects on the material world without any known physical mechanisms, such as muscle action, being involved. Figure 9.1 diagrams the basic model of PK. An agent is given instructions to make something happen simply by wishing for or willing it, and is physically separated from the target materials so that no ordinary physical forces are of any use.

There have always been reports that people caused resting objects, like a bottle sitting solidly on a tabletop, move by force of will alone, but it’s rare (but not unknown) to see events like this under laboratory conditions, where possible fraud or other material explanations can be completely ruled out. Many alleged PK events, for example, were produced in the darkened rooms of mediumistic séances as proof that spirits existed, but so many of these were revealed to be fraudulent when investigated closely. And yet, with a few mediums, such as Daniel Dunglas Home (pronounced “Hume,” 1833–1886), major movements of physical objects occurred under good observational conditions in hundreds of cases. Putting aside for the time being the question of whether such instances proved the existence of spirits, were they paranormal? Were they PK?

I’ve found it psychologically interesting that most people, including most parapsychologists, find it easy to ignore all the reports about D. D. Home and other similar mediums. I’ve decided that there’s some kind of psychological principle at work, an attitude on the order of “We moderns are so very, very smart, not like people in the old days, who were dumb and credulous, easily fooled, so if I don’t like any report more than twenty years old that attests to things I don’t want to believe in, I needn’t go to the bother of actually finding flaws in it; I can just dismiss it as ‘old’ and ‘anecdotal,’ and forget about it.”

I can’t think of any good reason why an educated group of men and women a hundred years ago were any better or worse than we are at observing things under good observational conditions, so I take most of the reports about D. D. Home seriously. For example, accordions, in rooms illuminated by candles or lanterns, were often seen and heard to play recognizable tunes, even though they weren’t being touched by Home or anyone else, or were being touched only with one hand. Consider this report by Sir William Crookes (1832–1919), a distinguished early scientist who investigated Home under stricter laboratory conditions than usually obtained at séances. (26)

I find Crookes’s description (1926) of some accordion research with Home so charming in its language, as well as valuable, that I reproduce it at length here:

Among the remarkable phenomena which occur under Mr. Home’s influence, the most striking, as well as the most easily tested with scientific accuracy, are (1) the alteration in the weight of bodies and (2) the playing of tunes upon musical instruments (generally an accordion, for convenience of portability) without direct human intervention, under conditions rendering contact or connection with the keys impossible. Not until I had witnessed these facts some half-dozen times and scrutinized them with all the critical acumen I possess did I become convinced of their objective reality. Still, desiring to place the matter beyond the shadow of doubt, I invited Mr. Home on several occasions to come to my own house, where, in the presence of a few scientific enquirers, these phenomena could be submitted to crucial experiments.

The meetings took place in the evening in a large room lighted by gas. The apparatus prepared for the purpose of testing the movements of the accordion consisted of a cage formed of two wooden hoops, respectively 1 ft. 10 ins. and 2 ft. diameter, connected together by 12 narrow laths, each 1 ft. 10 ins. long, so as to form a drum-shaped frame, open at the top and bottom; round this 50 yards of insulated copper wire were wound in 24 rounds, each being rather less than an inch from its neighbour. These horizontal strands of wire were then netted together firmly with strong so as to form meshes rather less than 2 ins. long by 1 in. high. The height of this cage was such that it would just slip under my dining table, but be too close to the top to allow of the hand being introduced into the interior, or to admit of a foot being pushed underneath it. In another room were two Grove’s cells, wires being led from them into the dining room for connection, if desirable, with the wire surrounding the cage.

Figure 9.2 Crookes’s Experiments:

Artist’s Sketch of D. D. Home with One Hand on End of Accordion

Mounted in Shielding Cage

The accordion was a new one, having been purchased by myself for the purpose of these experiments at Wheatstone’s in Conduit Street. Mr. Home had neither handled nor seen the instrument before the commencement of the test experiments. In another part of the room, an apparatus was fitted up for experimenting on the alteration in the weight of a body.…

Before Mr. Home entered the room, the apparatus had been arranged in position, and he had not even the object of some parts of it explained before sitting down. It may, perhaps, be worthwhile to add for the purpose of anticipating some critical remarks which are likely to be made, that in the afternoon I called for Mr. Home at his apartments, and when there he suggested that, as he had to change his dress, perhaps I should not object to continue our conversation in his bedroom. I am, therefore, enabled to state positively that no machinery, apparatus or contrivance of any sort was secreted about his person.

The investigators present on the test occasion were an eminent physicist, high in the ranks of the Royal Society (Sir William Huggins, F.R.S.), a well-known Serjeant-at-Law (Serjeant Cox), my brother, and my chemical assistant.

Mr. Home sat in a low easy chair at the side of the table. In front of him under the table was the aforesaid cage, one of his legs being on each side of it. I sat close to him on his left, and another observer sat close to him on his right, the rest of the party being seated at convenient distances round the table.

For the greater part of the evening, particularly when anything of importance was proceeding, the observers on each side of Mr. Home kept their feet respectively on his feet, so as to be able to detect his slightest movement.

The temperature of the room varied from 68 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Mr. Home took the accordion between the thumb and middle finger of one hand at the opposite end to the keys [woodcut figure omitted] (to save repetition, this will be subsequently called “in the usual manner”). Having previously opened the bass key myself, and the cage being drawn from under the table so as just to allow the accordion to be passed in with its keys downwards, it was pushed back as close as Mr. Home’s arm would permit, but without hiding his hand from those next to him [second figure omitted]. (27) Very soon the accordion was seen by those on each side to be waving about in a somewhat curious manner; then sounds came from it, and finally several notes were played in succession. Whilst this was going on, my assistant went under the table and reported that the accordion was expanding and contracting; at the same time, it was seen that the hand of Mr. Home by which it was held was quite still, his other hand resting on the table.

Presently the accordion was seen by those on either side of Mr. Home to move about, oscillating and going round and round the cage, and playing at the same time. Dr. Huggins now looked under the table and said that Mr. Home’s hand appeared quite still whilst the accordion was moving about emitting distinct sounds.

Mr. Home still holding the accordion in the usual manner in the cage, his feet being held by those next him, and his other hand resting on the table, we heard distinct and separate notes sounded in succession, and then a simple air was played. As such a result could only have been produced by the various keys of the instrument being acted upon in harmonious succession, this was considered by those present to be a crucial experiment. But the sequel was still more striking, for Mr. Home then removed his hand altogether from the accordion, taking it quite out of the cage, and placed it in the hand of the person next to him. The instrument then continued to play, no person touching it and no hand being near it.

I was now desirous of trying what would be the effect of passing the battery current round the insulated wire of the cage, and my assistant accordingly made the connection with the wires from the two Grove’s cells. Mr. Home again held the instrument inside the cage in the same manner as before, when it immediately sounded and moved about vigorously. But whether the electric current passing round the cage assisted the manifestation of force inside, it is impossible to say.

The accordion was now again taken without any visible touch from Mr. Home’s hand, which he removed from it entirely and placed upon the table, where it was taken by the person next to him, and seen, as now were both his hands, by all present. I and two of the others present saw the accordion distinctly floating about inside the cage with no visible support. This was repeated a second time after a short interval. Mr. Home presently reinserted his hand in the cage and again took hold of the accordion. It then commenced to play, at first chords and runs, and afterwards a well-known suite and plaintive melody, which it executed perfectly in a very beautiful manner. Whilst this tune was being played, I grasped Mr. Home’s arm below the elbow and gently slid my hand down it until I touched the top of the accordion. He was not moving a muscle. His other hand was on the table, visible to all, and his feet were under the feet of those next to him….

Alas, we don’t seem to have a D. D. Home around nowadays! Why? No one knows, but there has been speculation that the times have changed too much. In Home’s day, many people believed in spiritualism, and this gave a useful belief and social support system for Home to work in. Anyway, we don’t have any Homes, so we must work at a much less spectacular level.

In drawing the basic process diagram for PK, I showed dice as the target. The use of dice was inspired by a professional gambler, who dropped into J. B. Rhine’s laboratory at Duke University in the 1930s. He told Rhine that he shot craps for a living and made a decent living at it—and he didn’t cheat. But he’d recently read an article by a mathematician who showed that it wasn’t possible to make a living at craps; the odds were too much against you. “So,” the gambler likely asked, “how do I manage to be successful? Why do the dice come up the way I need them to so often?”

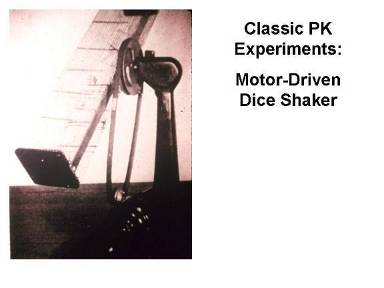

Classical parapsychological studies thus used thrown dice as the PK targets. Throwing dice is a multiple-choice-type test, like card guessing, and we can know precisely what the chance expectation is, one sixth of the desired target faces. An agent, the person attempting to mentally influence the roll of the dice, usually shielded from exerting normal influences by distance, barriers, or both from the surface where the dice were thrown, was asked to will them to come up in a certain pattern. The pattern would be something like aiming for ones for the first ten trials, twos for the second ten, and so on, equal numbers of all faces to compensate for any mechanical biases in the dice. (28) Figure 9.3 shows the highest development of this classical parapsychological technique, where the dice were tumbled about in a rotating wire cage and at some random point a timer opened the door in one end of the cage, allowing the dice to fall and bounce on the recording surface.

Figure 9.3 PK Dice Apparatus

Many experiments showed systematic changes in the die faces that came up. As reported in his outstanding book, The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena (1997), parapsychologist Dean Radin, along with psychologist colleague Diane Ferrari, performed a meta-analysis of 73 English language publications, representing the efforts of 52 investigators from 1935 through 1987. In this half-century time span, 2,569 would-be agents altogether had tried to mentally influence the outcome of just over 2.6 million dice throws in 148 different experiments. There were also just over 150,000 dice throws in 31 control studies where no one was attempting to influence the outcomes.

To make all the experiments read on the same scale, their results were mathematically recalculated as if chance were 50 percent. The control experiments showed that empirically, dice behaved just as we’d expect them to, with a “hit” rate of 50.02 percent.

For the combined experimental studies, though, where would-be agents were attempting to get more hits, the scoring rate averaged 51.2 percent. That’s not much in an absolute sense but has odds of more than a billion to one against being due to chance. The great majority of the time, the agent’s wishes had no effect, but every once in a while, a tumbling die was influenced to come up the desired way.

As with the earlier meta-analysis for precognition reported in chapter 8, Radin and Ferrari considered the file-drawer problem. Were lots of unsuccessful PK studies not being published, so the successful results were really a chance artifact? Only if an astonishing 17,974 unsuccessful studies were languishing in file drawers, or to put it another way, only if 121 unsuccessful, unpublished studies had been done for each successful, published one. Nor were less methodologically rigorous studies any more successful than more rigorous ones.

Nowadays dice are almost never used, and the targets in PK experiments are most likely to be the states of electronic RNGs. It’s more convenient to do them that way, because you can automate the whole experiment to preclude human errors, and the data’s already in computerized form to allow for more in-depth analyses. The effects are usually small but statistically significant.

Staying with Radin’s comprehensive review in The Conscious Universe, he and psychologist Roger Nelson at Princeton University performed a meta-analysis of 152 studies, published from 1959 to 1987. The reports covered 597 experimental PK series, where would-be agents tried to influence the RNG’s outcome, and 235 control studies.

As expected, empirical results in control studies continued to meet mathematical expectation: 50 percent hits. But the hit rate in the experimental studies was 51 percent, again, small in absolute terms but with odds against chance of a trillion to one. The level of results was very similar to that of the dice-tossing studies, so we’re probably dealing with the same process here: a small but significant PK effect. And as with the dice studies, poorer methodology in the earlier studies that might’ve produced more artifacts didn’t have any significant effect, and it would take 54,000 insignificant, unpublished studies languishing in file drawers to take away the significance of the published studies.

Many more PK studies with electronic RNGs have been published since Radin and Nelson’s meta-analysis, the PK effect continues to manifest, and analyses and theories get more sophisticated all the time. The size of the PK effect remains about the same though.

Biasing an electronic RNG slightly, by intention alone, may seem trivial compared to reports of an untouched accordion playing a tune in D. D. Home’s presence. On the other hand, there’s something quite mind blowing about these RNG results. What’s the target? If you try to influence a tumbling die, you have an implicit, commonsense model that you need to mentally “push” with just the right amount of force at just the right angle at just the right moment on the tumbling die, and that’ll force it to come up the way you want. But what do you “push” on while trying to influence electronic circuits that are sitting in a box? What level of reality are you working on? Certainly not a commonsense reality of push and shove.

My personal introduction to PK studies happened in summer 1957, between my sophomore and junior years at college, when I had a summer job as a research assistant at the Round Table Foundation in Glen Cove, Maine. Andrija Puharich, the physician and researcher who ran the foundation, was visited by some people from Virginia who claimed various psychic abilities that we tried to test. The person I’ll focus on here claimed ability to psychokinetically control the spin of a coin, usually a silver dollar, so the desired side would come up as the coin slowed and finally fell to the tabletop.

I was quite suspicious of William Cantor, the man who did this. Cantor could get 80 to 90 percent of the desired target face, but he was too glib and self-assured for me, and he was the one spinning the coin, so I was sure there was some mechanical trick to the way he spun it. It looked as if the coin was spun hard and would spin for ten to fifteen seconds or more before slowing down enough to noticeably wobble, and then you could often glimpse the desired target face but not the other face as it spun. It was a fascinating visual display. But all the tricks I tried in spinning the coin myself didn’t work; I got 50 percent.

I watched Cantor get strong results dozen of times, and I kept trying to figure out the trick but couldn’t. I realized later that he was quite aware of my suspicions and frustration, and watched it build and build. Finally, when I was clearly very frustrated, he let me in on the secret. If you wanted the coin to come up heads, for instance, just before spinning the coin, you tilted it slightly off the vertical position so that the heads side was tilted back. I was delighted to now know the secret and have my suspicions confirmed, and I then started getting 70 to 80 percent hits on my spins!

But after a few minutes or so of this, I realized I’d already tried this particular trick before, and it hadn’t worked! Indeed, using what physics I knew at the time, it seemed to me that if you gave the silver dollar a good spin, it wouldn’t matter if it were tilted a little before you spun it; the momentum of a hard spin would straighten it up. (I’m not sure if this is literally true, but it’s what I believed at the time.) My scores fell back to chance, 50 percent—and stayed there.

Cantor had been deliberately playing with me, letting me get very frustrated until I was desperate for a belief that would explain things for me. Then he gave me this false explanation, knowing that in my frustration, I’d grasp at it—and start getting results! He’d done it with others before.

It was a good lesson in psychology for me, whether there was any PK involved or not. Belief systems can empower us—even if they’re factually wrong! Or disempower us, depending on the beliefs.

To give the flavor of experimental PK studies, I’ll describe my few formal studies, inspired by this early experience.

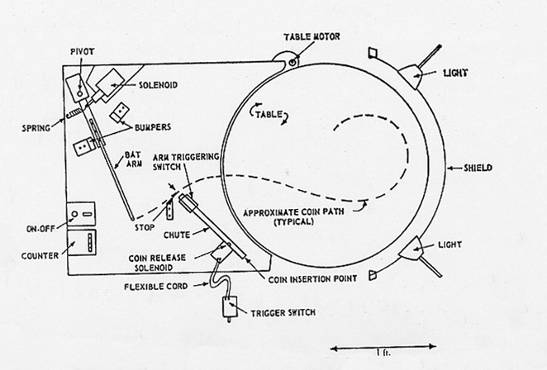

Almost two decades later, much more mature (or so I thought) and a psychology professor at the University of California, Davis, I came back to this spinning-silver-coin puzzle, and with the help of my students Marlin Boisen, Victor Lopez, and Richard Maddock, conducted several experiments (1972). Psychologically, I felt that a spinning silver coin, like a big, shiny silver dollar, was an excellent target for PK: it was dramatic, and you could often see one face or the other, rather than a blur, as it spun, making you feel as if you were focusing on it in some mysterious fashion. Its whirring sound as it spun and the clatter as it finally lost momentum and fell drew in your attention. The whole procedure was both fascinating and fun, which I think are important conditions when you’re trying to look for psi ability in the laboratory. But letting the test person, the agent, spin the coin wasn’t satisfactory, since we didn’t know if you couldn’t influence the outcome by normal means that way. So we devised a mechanical apparatus, photographed in figure 9.4 and diagrammed in figure 9.5, to spin the coin.

Fig. 9.4 Reprinted by permission of the

Journal of the Society for Psychical

Research

A silver dollar, selected to be as unbiased as possible, and as shiny as possible, was placed in the clear, plastic holder shown at the middle bottom of the figure. When the agent was ready for a trial, the experimenter, holding a switch attached to the apparatus by a soft, flexible cord, so that he couldn’t accidentally pull on the apparatus, pushed the start button. This pulled back a little pin that held the silver dollar in place so that it now rolled down the inclined chute, pushing on a switch near the bottom of its roll. This triggering switch activated a mechanical bat arm with a padded neoprene tip, whose forceful swing hit the edge of the coin just as it rolled out of the chute, spinning it rapidly and knocking it horizontally out onto the circular tabletop. Rubber bumpers absorbed the momentum of the bat arm at the end of its swing, and then a spring returned it to its rest position.

The round table rotated very slowly (about one revolution per hour) by means of a roller and motor at its edge. This was designed to prevent uneven table wear that might affect the operation of the coin.

Two small, high-intensity lamps illuminated the spinning coin from the right-hand side of the machine. The subject sat or stood between these two lamps. A shield, about four inches higher than the top of the round table and extending to the floor, was between the subject and the apparatus. This shield was supported directly by the floor and had no physical connection with the apparatus. The subject was told not to touch the shield, but if he did accidentally bump it, he still wouldn’t physically affect the apparatus.

The entire apparatus was shock mounted, to eliminate vibrations transmitted through the floor, in the following way. (29) A large automobile tire was laid flat on the floor, a piece of plywood laid on top of it, and then several concrete blocks were placed on it. Another automobile tire was placed on top of that, and the coin-spinning apparatus was on top of this. This inexpensive method of shock mounting was extremely effective in eliminating vibration and movement transfer. Some lead bricks were slid back and forth on the underside of the apparatus proper to level it; they also added additional mass on top of the tires for further isolation from any floor-transmitted shocks.

The subject also held a clear-plastic deflecting mask over his nose and mouth. This allowed him full physical view of the spinning coin, with no intervening materials, but prevented any effects from his exhalations. During experiments, the coin was never fired unless the subject was holding the mask over his mouth and nose. Neat, eh? As a lifelong gadgeteer, I loved this apparatus!

Fig. 9.5

But, darn it—three studies, run by each of my three student colleagues, didn’t show significant results, except for a possible decline effect in one. Maybe there is no PK? I didn’t consider this a likely interpretation, because so many studies by others had found evidence for it, but there was no PK manifested here, perhaps because we used ordinary college students as agents rather than have someone specially selected as apparently already having PK ability?

That’s one of the realities of research: you set things up with high hopes of getting interesting findings, and what you expect doesn’t happen. You try to learn from what did happen, and think about why you didn’t get what you expected. There’s always a sense of disappointment when things don’t work, but there’s also satisfaction in knowing you’ve done a well-designed experiment.

And then, just to keep my mind from resting resignedly but peacefully, the same apparatus was later used when the well-known British psychic Matthew Manning visited my lab. He did three experimental runs with chance results and didn’t want to do any more, feeling he had no psychic contact with the coin. That’s quite understandable; who wants to work at something he doesn’t have any success with? As we discovered after he’d left, though, the coin used showed a significant bias toward heads, 56 percent in Manning’s experimental runs. But we’d calibrated the coin extensively before (and after) Manning’s visit: it was a coin with a significant tails bias of 55.6 percent (Palmer, Tart, and Redington 1979). What do we make of that?

This pattern of not getting the clear evidence of psi phenomena that you expect, but getting some sort of secondary effect, is relatively common in parapsychological studies. Sometimes it’s just a chance happening—if you do analysis after analysis, some will be apparently significant by chance alone. And yet sometimes, it has led some parapsychologists to think there’s something inherently “perverse” about psi phenomena, that we’re being “teased” by it. It’s as if psi happens often enough to keep us interested, but not reliably or strongly enough for us to be certain about it or apply it very well. I’ve certainly felt that way at times.

Beyond the simple venting of frustration by thinking this way, though, I’ve sometimes had a thought that’s heretical in current scientific thinking. Mainstream science and much parapsychology implicitly, if not explicitly, assumes that we, humanity, are the most, if not the only, intelligent creatures in the universe. So when we do experiments to extend our knowledge, the outcome is a function only of the natural laws governing things and our cleverness in investigating them. But suppose there is, as we consider in this book, a spiritual reality, perhaps with spiritual beings of some sort existing in it? Are the desires and qualities of these spiritual beings part of our experiments also? Is the idea of being “teased” with inconsistent but unignorable psi results more than just a metaphor?

I wrote the preceding description of my own PK experiments with spinning silver coins largely from memory, but in putting finishing touches on this chapter, I went back and reread my original report (Tart et al. 1972) to ensure my accuracy about details. I was accurate except for one thing. Although I remembered William Cantor’s psychological manipulation of me so that I apparently showed some PK for a few minutes, I had completely forgotten about the experiment Andrija Puharich and I did with him as a more rigorous test of his claimed PK ability.

In the last test before Cantor went back to Virginia, we decided to do one hundred coin-spinning trials with him. We did this in a special environment that Puharich believed enhanced ESP ability (and perhaps psi ability in general), a solid-wall Faraday cage. (30) That research is a fascinating story, too complex to go into in this book, but I’ve written about it and reported one confirmatory study of my own elsewhere (see Tart 1988a). Here’s what happened in this PK test; I quote my earlier report (Tart et al. 1972, 143) since I don’t quite trust my memory after realizing I’d totally forgotten this:

The most well-controlled test, carried out just before W. C. [William Cantor] had to leave the foundation, was performed with an a priori agreement that there would be one hundred trials (spins of the coin), and that W. C. would try to influence the coin to fall heads on all of these. No trial was to be counted unless the coin spun for at least five seconds. It was spun by holding it vertically upright between index finger and tabletop, and flicking it on edge rapidly with the index finger of the opposite hand. The test was carried out in a small copper-shielded room (a Faraday cage) with W. C., Dr. Andrija Puharich (A. P.), and C. T. [myself] sitting around three sides of a small, glass-topped coffee table. W. C. did not touch the table or the silver dollar used at any time during the test. A. P. spun the coin, while C. T. kept a record of the number of trials and the outcome of each trial, with A. P. checking C. T.’s record of outcomes as it was made. W. C. was in perfect view at all times, and could not surreptitiously touch the table, blow on the coin, or otherwise influence it in any known, physical manner.

The outcome of this test was 100 heads, the chosen target, in 100 trials. The odds against this happening by chance alone are astronomical. (31)

It’s true that I now write about this fifty years later, and that’s a long time, but to just forget that I saw one hundred heads in a row?

Just as the unexpected appearance of massive precognitive psi-missing in my immediate-feedback training study (see chapter 8) made me aware of a deep kind of resistance to the very idea of precognition, perhaps I have some deep resistance to the very idea of PK, in spite of my intellectual acceptance of it?

My possible resistance or not, PK is one of the “big five.” Sometimes the human mind can affect that state of the material world by wishing, with no known material intervention. Perhaps there’s more than one kind of PK, such as a very small-sized way of biasing otherwise-random events, like falling dice or electronic RNGs, but also a much more massive kind of PK that makes accordions play when they aren’t being touched.