Chapter 11

* * *

MAYBE (Late Middle English [origin: from “it may be” Cf. “mayhap”]: Adverb—Possibly, perhaps. Noun—What may be; a possibility. Now rare. —Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “maybe”

* * *

As for the psi phenomena in the previous chapters, the “big five,” each has hundreds of well-controlled experiments supporting its existence, as well as hundreds of thousands of events reportedly happening to ordinary people in everyday life that are most likely caused by these psi functions. That sounds like a lot of evidence, but remember that scientific parapsychology is a very small-scale enterprise and it’s taken decades to collect this evidence. How small? My current rough estimate is of a few dozen scientists at most, almost all of them working on parapsychological research on a strictly part-time basis. (For a more exact, if older, comparison, see Tart 1979b.) If I compared parapsychology to any mainstream research area in fields like biology, chemistry, physics, or medicine, I doubt that the total, worldwide parapsychological research in a year would equal an hour of any mainstream field’s research. While we have more than adequate evidence to support the existence of the big five, there has been little definitive research, given this lack of resources, to tell us about their nature, ways of improving their operation, their implications, or the like.

Besides the big five, there are a number of possible psi phenomena I call the “many maybes” that, if they’re real, have important implications for what’s spiritually possible. They all have enough, even if few, studies that I find I have to consider them possible realities, but not enough to be fairly certain of their reality or to form a reliable reality basis for understanding spirituality as the big five do. I introduce some of these many maybes in this and the following chapters. Note that the iffy status of these phenomena would make some parapsychologists (of the few that exist) disagree with me about their reality status; with some thinking that some of these phenomena have pretty solid support, and others considering them to be so unlikely that perhaps I shouldn’t even discuss them until there’s more evidence. But just as we can’t live life only on the basis of what’s certain, we can’t base our spirituality only on what’s certain; we need to get on with life, so we have to stretch some to get a fuller picture.

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve always found the idea of precognition, that the inherently unpredictable future can sometimes be foretold by some kind of psi ability, mind boggling, to say the least. It makes no sense at all to me, which, of course, says something about the nature of my mind’s organization, and not necessarily anything about reality. Yet the weight of the evidence forces me to include precognition in the big five. At a conceptual level, the reality of precognition reminds me that we understand only a little about the nature of time.

So, if the mind can sometimes get information about the future with psi ability, it implies that some psychic aspect of mind is not always stuck in the present. If this aspect of mind can view into the future, shouldn’t it be able to view into the past? Shouldn’t we have a logical category of postcognition?

We do have the logical category and name, but there’s a real methodological problem in trying to study postcognition. Assume that the mind gets information from the past. How do we verify that this information is correct? By checking against presently existing records of the past, such as books, deeds, wills, people’s memories, digging up an archeological site, and so on. If there are no presently existing records, we can’t check ostensible postcognition for accuracy, and it remains merely a speculation.

But if present-time records exist that verify postcognition, how do we know that the percipient didn’t use “simple,” present-time ESP, clairvoyance, or telepathy, to read the records rather than contact the past or read the mind of someone who knew about the past? Or precognitively read the minds of investigators who later dug up the information about the past?

No one has thought of a satisfactory solution to this methodological problem. With precognition experiments, you can try to predict a future event that’s determined by so many different factors that it’s hard to imagine a mind reasoning to a correct prediction from present information, even if a good deal of clairvoyant and telepathic input about the present state of things were available, or even if some unconscious, psychokinetic manipulation of present events to try to force a particular future state occurred. For example, the classic precognition studies asked percipients to predict the future order of decks of target cards. Normal sensory knowledge or clairvoyant knowledge of the current order of the target deck wouldn’t help, because that order would be destroyed and randomly reordered by thorough shuffling of the deck. Shuffling randomizes, because we can’t control the small size of the cards and high speed of their motion in shuffling, in terms of our material, human senses (barring cheating by card sharks, which need not concern us here).

But suppose, through some combination of clairvoyant knowledge of where particular cards were in the deck at a given time and psychokinetic “pushes” or “alterations of friction,” the unconscious mind of the ostensible precognizing percipient could influence the shuffling process to make desired cards end up in the position that had been predicted, an ace third down from the top, for example? It would only need to happen occasionally to produce statistically significant results that misled us to think we had evidence for precognition.

In point of fact, there were some classical card-guessing studies designed to test this idea. They were designated psychic shuffle studies. Experimental participants, acting as agents in this case, were given a deck of target cards, told to shuffle them, facedown, a stated number of times, while wishing or intending that the cards would come up in a certain order, say the red cards in the top of the deck and the black ones on the bottom. An experimenter supervised the shuffling, of course, to prevent agents looking at the cards or otherwise cheating. Results were generally positive; that is, significantly more of the desired cards ended up in the designated target positions than would be expected by chance (Kanthamani and Kelly 1975). (32)

The psychic shuffle is a very interesting result on its own, but because parapsychologists wanted to test precognition, not PK, further steps were added, outside what we’d think of as reasonable possibilities of manipulation by percipients or agents and experimenters, to determine the final random order of target cards. So the protocol might call for something like this:

1. Ask percipient to write down the order the deck will be in at a specified time tomorrow.

2. Send the percipient home.

3. Half an hour before that specified time, the experimenter thoroughly shuffles the facedown deck a large, pre-specified number of times.

4. The experimenter then consults that day’s morning newspaper to find the high temperature in some specified location, say Kansas City, divides that number by three, counts down that number of cards in the shuffled deck, and cuts the target deck there.

5. The experimenter repeats the above step for several other locations.

When you get significant precognition results under conditions like these—and this did happen—it’s really stretching it to say that this wasn’t really precognition, that the ostensible percipient really was a PK agent who not only pushed cards around during later shuffling but affected the high temperature in Kansas City, and so on. You make the PK alternative more and more complex. So, we can feel highly confident in theorizing that the mind can actually get information from the future at times.

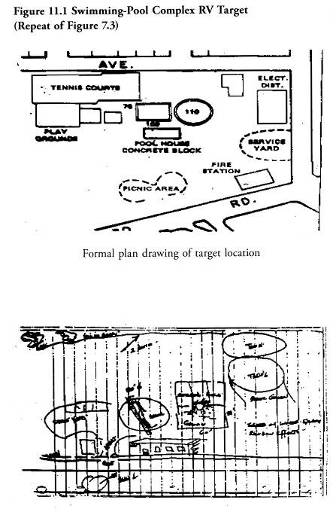

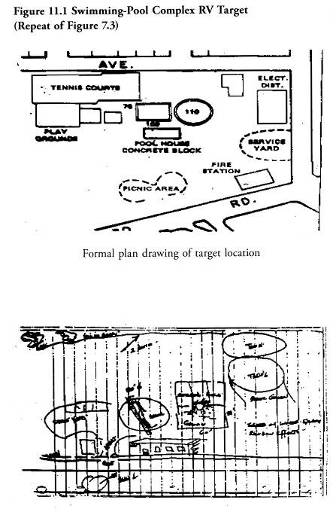

Yet things can happen that make us suspect postcognition is real, even if we can’t come up with a satisfactory experimental design. For example, recall the clairvoyant RV study described in chapter 7, where the target site was a swimming-pool complex in Palo Alto. Here, for convenience, is a repeat of figure 7.3, the plan drawing beside remote viewer Pat Price’s sketch of what he thought was there.

Remember Targ and Puthoff’s description (1977, 52–54):

…Pat’s drawing is shown…in which he correctly described a park-like area containing two pools of water: one rectangular, 60 x 89 feet (actual dimensions 75 x 100 feet); the other circular, diameter 120 feet (actual diameter 110 feet). He was incorrect, however, in saying the facility was used for water filtration rather than swimming. With further experimentation, we began to realize that the occurrence of essentially correct descriptions of basic elements and patterns coupled with incomplete or erroneous analysis of function was to be a continuing thread throughout the remote-viewing work.

As can be seen from his drawing, Pat also included some elements, such as the tanks shown in the upper right, which were not present at the target site. The left-right reversal of elements—often observed in paranormal perception experiments—is likewise apparent.

All in all, this was an excellent, present-time RV, spoiled mainly by the erroneous inclusion of two water towers and the idea that the facility was used for water filtration rather than swimming. One can imagine this as imaginative overlay through associations with (correctly perceived) water or the like.

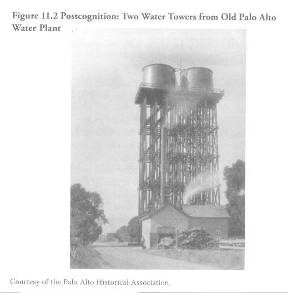

And then many years later, long after Pat Price had died, Russell Targ, who was a resident of Palo Alto, received a routine newsletter from the city of Palo Alto. Its cover, a historical photo, showed two water towers at a long-since-gone water filtration plant. I’ve obtained a better-quality photo, courtesy of the Palo Alto Historical Association. Here it is.

The note on the back of the photo reads, “The city water plant with adjacent reservoir was built in 1898 at Newell and Embarcadero Roads.” That’s the present location of the park and swimming-pool complex. What was considered imagination or a mistake on Price’s part was correct—far many years earlier.

One of the things the SRI remote-viewing experimenters gradually learned over the years from other studies than the one this example comes from, especially precognitive RV studies, was that it was a good idea to not simply ask, “Describe the place where X is,” but rather “Describe the place where X is, as it looks now.”

Do past things or events leave psychic traces that can be picked up in the present, is this another reminder of how little we understand time, or both?

As I noted earlier, it’s conceptually frustrating to deal with the idea of postcognition, because the only way to verify its accuracy, if it is indeed real, is by checking against physical records or living people’s memories, and that means that there’s a source of current-time information that might account for the results, making them due to “mere” clairvoyance or telepathy. But since the existence of precognition forces us to question the adequacy of our conventional ideas about the nature of time and some ideas associated with spirituality deal with unusual conceptions of time (33), I want to give another example of what might be postcognition—or might be “mere” clairvoyance but certainly isn’t telepathy from the living. And I do have to accept the fact that just because my conceptual system has trouble with something like precognition or postcognition doesn’t mean it isn’t real.

In chapter 7, we looked at one aspect of Project Deep Quest, an experiment of parapsychologist Stephan Schwartz, the aspect of interest to us being how it ruled out electromagnetic radiation as a carrier of the information in RV. One of Schwartz’s main interests has been the applied use of RV in archeology. Part of Project Deep Quest was the successful location of a century-old wreck lying hundreds of feet below the surface (this fascinating story is described fully in Schwartz’s 2007 book Opening to the Infinite, which also has his comprehensive instructions on how to use RV). Postcognition? “Mere” clairvoyance? Certainly, the location was not known to any living people, nor were there any records locatable by marine-wreck experts about the wreck’s location.

I’m intrigued even more, though, by one of Schwartz’s Egyptian archeological projects that extends much farther back in time: the location of a specifically detailed site in the city of Marea, now buried under the desert sand. You can find a detailed report on this project online at www.stephanaschwartz.com, but I’ll describe its highlights here.

Marea, founded several centuries before the Christian era, was a thriving trade center and regional capital, built on the shores of a large lake (Lake Maryut), with a canal to Alexandria and a river connection to the Nile. It was occupied and still functioning as a trade center as late as the sixteenth century, but today it lies hidden beneath a desert of low, semiarid hills. The lake has been reduced to isolated ponds of brackish water, none more than a few feet deep, and very little archeological work has been done on the site.

Schwartz felt Marea would be an excellent area to test the practical usefulness of remote viewing, because the only modern archeological survey, done in 1976, three years prior to Schwartz’s project, found little. That survey used the then most current electronic remote-sensing technologies and search methodologies for archeology, including aerial photography, topographical survey, and proton precession magnetometer measurements. It concluded that there were lots of subsurface structures, which would be hardly surprising when you knew the ruins of a city were under the desert and that the streets were laid out in a grid pattern, like modern cities. Otherwise, it concluded that there was probably little, if anything, left under the surface but foundations. There was nothing very specific in the survey, which left lots of room for RV to add something.

Two remote viewers, George McMullen, a Canadian who’d worked extensively with another archeologist in the past (haven’t you always wondered how in the world archeologists know where to dig?), and Hella Hammid, mentioned in chapter 7, the Los Angeles photographer who was originally selected as a “control,” a person who thought she had no psychic abilities but turned out to be quite talented in SRI remote-viewing studies, were flown to Egypt for this project. Neither had ever heard of Marea: indeed, most archeologists have never heard of Marea; it’s an obscure site.

Schwartz usually began psychic archeology projects by having viewers, working at home, look at large-scale maps of the area of interest while being instructed to “map dowse,” meaning to mark on the map the areas they sensed would contain specified kinds of archeologically interesting objects. Such marked maps would then be overlaid on a light table to see where the markings of the remote viewers, who worked independently of each other, overlapped. This is a standard engineering approach for working with “noisy” signals, that is, signals that contain errors as well as correct information. Such averaging tends to cancel out errors but make the agreed items stand out. But Schwartz couldn’t get any adequate maps of that area of Egypt containing Marea before going to Egypt, and even after getting there, could obtain only one map, which was on an almost useless scale.

So, Schwartz worked with Fawzi Fakharani, a prominent Egyptian professor of archeology at the University of Alexandria, who, while quite skeptical of RV, had the political connections to allow for excavation at the Marea site. On the morning of April 11, 1979, McMullen and Hammid were taken in separate vehicles to an area of desert chosen by Fakharani that was out of sight of the area of Marea, about six miles from it. After the stop, Schwartz decided to accompany McMullen during his first attempt to locate Marea, while Hammid was driven away out of sight. After they’d left, McMullen was given the following charge by Fakharani:

1. Locate the ancient city of Marea, which is somewhere within an area roughly 24 kilometers on a side, a form 576 square kilometers in size (an area roughly equal to half the city of Los Angeles, which is 15 by 15 miles or 225 square miles). After locating the city, locate a building that has either tile, fresco, or mosaic decoration in it.

2. Within the chosen building, locate the walls, windows, doors, and depth at which the floor would be found.

3. Describe any artifacts or conditions that would be found within the building site.

If, like Professor Fakharani, you were very skeptical (I would say “pseudoskeptical,” as discussed in chapter 3) of the reality of RV, this was basically an impossible task and McMullen was bound to fail.

Followed by Schwartz with a tape recorder and by a camera crew, McMullen then wandered off across the sands. McMullen seemed in something of a trance state, ignoring the hundred-degree temperature, stinging winds, and sand flies, occasionally giving scattered impressions about long ago, most of which were uncheckable, but he finally reported that he knew where he wanted to go. Schwartz reports (2000): “McMullen and the author then walked back to where Fakharani and his assistant were waiting, whereupon McMullen knelt in the sand, sketched an outline of Marea as it appears today, and described for Fakharani where the University of Alexandria’s dig was located and what the area looked like…Fakharani acknowledged on camera the accuracy of the description.”

Fakharani then drove the crew to Marea and his dig site. McMullen wandered around for some time suggesting other dig sites (none yet excavated; this is expensive work!) and giving unverifiable impressions of how people lived in the ancient city; only physical structure remains can be checked by archeological work, not how people lived.

Schwartz (2000) notes that once again: “McMullen was charged again by Fakharani to ‘locate an important building—one with tile, fresco, or mosaic—something representative. It is for you to tell me where to dig.’”

Without hesitation, McMullen proceeded to walk up a hill on the south side of the ancient road. Once there, he did the following:

1. Quickly sketched in the outline of a building with several rooms and stated that the area described was only a part of a larger complex.

2. Located walls, one doorway, and the corners of the structure.

3. Indicated that the culture that had built this building was Byzantine.

4. Described the probable depth to the tops of the walls as being approximately “three feet” (.91 meters).

5. Indicated that there would be debris (dropped there after being taken from a different structure).

6. Said that one wall, the west one, would have tiles on it.

7. Explained the culture or cultures that had built or modified the building and its later use for storage.

8. Felt the crew should come across “a floor” of the structure at approximately “six to ten” feet (1.8 meters to 3 meters), although he confessed—somewhat distressed—“I can’t see the floor” (Schwartz 2000).

9. Said that several colors would be associated with the site, but felt green was the most prevalent, since he perceived it most strongly.

And here, because I want to encourage you to read the fascinating report (www.stephanaschwartz.com) and I don’t want us to wander too far afield from the main themes of this book, I’ll simply say that basically McMullen was revealed to be correct on all those details. The corners, wall, and door were where McMullen later drove in stakes; the tops were three feet down; there was debris dumped in the site; and the funny feelings about the floor related to the fact that the tile floor had actually been almost completely removed, leaving only the white subfloor and so forth.

Is there some real sense in which the “past” still exists? If so, is it only as a kind of stored “memory”? Or, is there indeed something very unusual about the ultimate nature of time, which perhaps various spiritual traditions have hinted at, that we’re a long way from understanding?