* * *

NEAR (Middle English [origin: from “near,” adverb]): Close at hand, not distant, in space or time.

DEATH (Old English): The act or fact of dying; the end of life; the final and irreversible cessation of the vital functions of an animal or plant.—Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “near” and “death”

* * *

Dennis Hill earned his BS degree in biochemistry back when that was sufficient training to become a working scientist. He was employed as a consultant in environmental chemistry software when he wrote to me in 2001. Hill reported the following near-death experience (NDE) to my website, The Archives of Scientists’ Transcendent Experiences (www.issc-taste.org). His experience occurred in November 1958 in a college infirmary in Fort Worth, Texas, although his description now incorporates descriptive terms from later spiritual seeking in life. He titled his description, “Ah, Sweet Death” (Hill 2001):

“Damn it, woman! That hurt!” The deadly penicillin injection hits a tight knot in the muscle that the body knows is the last gesture of resistance before giving up to the insidious invader.

The crusty night nurse regards me with a practiced dispassion: “Just pull up your pajamas, roll over, and go to sleep. I don’t want any more trouble from you.” She ambles back to her station in the otherwise unstaffed college infirmary.

I notice that something within me has become suddenly still and quiet. Has my heart stopped beating? I put my hand on my chest: nothing. I reach for the radial pulse with my other hand: nothing. Little sparkles of light dance before me as my vision begins to dim.

“Dave!” I call out to the other guy on the ward, who lives on my floor in the dorm.

Darkness sweeps in.

There is a sudden rush of expansion into boundaryless awareness. I feel utter serenity infused with radiant joy. There is perfect stillness; no thoughts, no memories. In the rapturous state, free from the limitations of time and space, beyond the body and the mind, I have no memory of ever having been other than This.

The Buddhists know about this state. They chant:

‘Gaté, gaté, paragaté,

parasamgaté. Bodhi swaha!’

(Gone, gone, utterly gone,gone without recall. O freedom!)

Gone without recall? Gone beyond remembering ever having been? O freedom! It is true!

In this vast and blissful stillness there is now movement. I am drawn toward a tunnel ringed in blue radiance. Into the tunnel, through no volition of my own, I continue on around the curve in the tunnel until I see a dot of white light that grows larger as if [I am] approaching it.

Maharaj Jagat Singh writes: “As the Soul hears the sound of the Bell and the Conch, it begins to drop off its impurities. The Soul then travels up rapidly, and flashes of the distant Light begin to come into view. Connecting the two regions is an oblique passage, called the Curved Tunnel. Only after crossing this tunnel does the Soul reach the realm of the Creator. Here the attributes of the mind drop off, and the Soul ascends alone. Once it reaches its Home, it merges in it, thereby setting the Soul free.” (Okay, so how did he know that the tunnel is curved?—around to the left, as I recall.)

Falling into the white light, I am somehow jerked back through the tunnel into the body. The precious fullness of bliss and peace is juxtaposed in the limitations of a body thumping wildly from the epinephrine injected into my heart. The rapture is gone. I am very angry at coming back.

The Sufi Master, Hazrat Inayat Khan, gives us this teaching, “Die before death.” The message here is to become established in the joyous tranquility of the inner Self so that when the body suddenly drops away, we will not be distracted by attachments to the world. In this way the Soul will complete its journey home. All of yoga is preparation for the last moment before and the first moment after leaving the body.

Next time I will be ready.

No fear, only the equipoise of the Indweller.

Hill’s simple comment (2001) on his experience is, “No fear of death. Persistent awareness of the utter stillness behind the mind and within all activity.”

Do you find that parts of this description don’t quite make sense for you? Or perhaps some part of you probably understands, but you can’t quite contact that part? That’s an illustration of the distinction I made between OBEs and NDEs in the previous chapter. A person’s consciousness during a simple OBE is pretty much like ordinary, “normal” consciousness, so she can describe it quite comprehensibly. But in an NDE, while there may be an initial OBE component, usually with consciousness seeming pretty much like normal, there’s usually an altered state of consciousness (ASC) involved, so there are important changes in the way consciousness functions. This ASC makes sense to you during the ASC, but this sense doesn’t transfer well to ordinary consciousness afterward; it’s state-specific knowledge and memory.

Many people who hear about NDEs think something like, “Wow! I wish I could have that experience and that knowledge!” I certainly did when I first read about them way back in the 1950s—without the hard and scary part of coming close to death, of course!

As NDE researcher P. M. H. Atwater (1988) and others have documented, however, it’s often not a simple matter that you start out “ordinary,” have an extraordinary experience, and then “live happily ever after.” Years of confusion, conflict, and struggle may be necessary as you try to make sense of the NDE and its aftermath, and to integrate this new understanding into your life. Part of that struggle and integration takes place on transpersonal levels that are very difficult to put into words, another part on more ordinary levels of questioning, changing, and expanding your worldview. (I’ll use the term “transpersonal” rather than what would often be synonymous, “spiritual,” as it has a more open connotation to it, whereas spiritual is usually associated with particular, codified belief systems. Appendix 4 elaborates on the transpersonal.) I’m not really qualified to write from a higher spiritual perspective, but I’ve gathered some useful information in my career about the nature of the world that may help with that part of the integration, and that’s one of my primary emphases in this chapter.

Philosopher and physician Raymond Moody, whose 1975 book Life After Life hit the best-seller lists (there has always been a deep, spiritual hunger in people) brought the NDE out of the closet, and it’s now widely known. As to actual occurrence, estimates today are that, due to modern medical resuscitation technology, millions of people may have had an NDE.

To give the general flavor of NDEs, here’s the “composite case” Moody (1975) constructed out of the common elements of NDEs. No one person is likely to experience all of these elements, or always experience them exactly in this order, but the overall flavor is conveyed nicely. I’ve italicized brief descriptive elements.

A man is dying, and as he reaches the point of greatest physical distress, he (1) hears himself pronounced dead by his doctor. He begins to (2) hear an uncomfortable noise, a loud ringing or buzzing, and at the same time feels himself (3) moving very rapidly through a long, dark tunnel. After this, he suddenly finds himself (4) outside of his own physical body but still in the immediate physical environment, and (5) he sees his own physical body from a distance, as though he’s a spectator. He (6) watches the resuscitation attempt from this unusual vantage point and is in a state of (7) emotional upheaval.

After a while he collects himself and becomes more accustomed to his odd condition. He notices that (8) he still has a “body,” but one of a very different nature and with very different powers from the physical body he has left behind. Soon, other things begin to happen. (9) Others come to meet and help him. (10) He glimpses the spirits of relatives and friends who have already died and a loving, warm spirit of a kind he has never encountered before. (11) A being of light appears before him. This being asks him a question, nonverbally, to (12) make him evaluate his life, and helps him along by showing him a panoramic, (13) instantaneous playback of the major events of his life. At some point he finds himself approaching some sort of (14) barrier or border, apparently representing the limits between earthly life and the next life. Yet he finds that (15) he must go back to the earth and that the time for his death has not yet come. At this point (16) he resists, for by now he’s taken up with his experiences in the afterlife and doesn’t want to return. He’s overwhelmed by (17) intense feelings of joy, love, and peace. Despite his attitude, though, he somehow reunites with his physical body and lives.

Later (18) he tries to tell others but has trouble doing so. In the first place, he can find (19) no human words adequate to describe these unearthly episodes. He also finds that others scoff, so (20) he stops telling other people. Still, the experience (21) affects his life profoundly, especially his view about death and its relationship to life.

The fact that Moody can construct a composite case that captures so much of actual NDE cases points out one of the things most important about NDEs: the enormous similarity of NDEs across a wide variety of people and cultures. If NDEs were nothing but hallucinatory experiences, as materialists want to believe, induced by a malfunctioning brain as a person dies, then we would expect great variation from person to person, and the qualities of the experience would be largely determined by the culture and beliefs of the each person experiencing the NDE. Instead, we have great similarity across cultures and belief systems, arguing that there’s something “real” about the NDE rather than its being nothing but a hallucination. Indeed aspects of the NDE often contradict the (previous) belief systems of the people experiencing them. (Former) atheists, for example, are embarrassed by meeting a being of light who’s so godlike, yet their descriptions of the being are very similar to people with other beliefs.

There are many things in life we believe, for example, not because we’ve had direct experience of them, but because others’ reports of their experiences are so similar. I’ve never been to Rome, for example, but am quite content to believe that Rome exists because of such consistency in others’ accounts. The NDE, then, is what we call psychologically an archetypal experience, a possibility if you’re human, whether your culture has prepared you for it or not.

A standard reason for materialistic pseudoskeptics to dismiss NDEs, when they pay any attention to them at all, as nothing but brain-based hallucinations is to emphasize the “near” part of NDE, noting that the person experiencing it wasn’t really dead. The person may have looked dead from the outside if she showed no obvious signs of a pulse or respiration, and may have even been declared dead by a doctor, but the fact that she recovered later tells us that she wasn’t really dead. Maybe there was still a lot of brain functioning going on. This is an important point, and one of the things we’d like to know about NDEs is just how “dead” was the person experiencing it? What exactly does “dead” mean?

Ideally we’d like sophisticated physiological measures taken on people who’ve just died and might revive and report an NDE. Realistically, though, most NDEs don’t take place in medical settings, and when they do, the emphasis, to put it mildly, is on resuscitating the patient as quickly as possible (the longer they’re without a pulse, the more probable the chances of brain damage), not on conducting an accurate physiological study of their bodily and nervous system state. In principle, for example, it would be useful to measure brain-wave activity (EEG) to see if there is any, but it takes a while to properly attach the needed electrodes for this, during which time oxygen starvation is continuing in the brain—and then the first massive electrical shock applied to the chest in an attempt to restart the heart would completely destroy the expensive EEG machine!

There’s one dramatic NDE case, though, where we know a great deal about what was happening in the patient’s brain, that of Pam Reynolds (pseudonym), written about by cardiologist Michael Sabom (1998). (48)

Pam Reynolds, singer and musician, needed surgery for a giant basilar artery aneurysm. This was a weakness in the wall of a large artery at the base of her brain, which had caused it to balloon out much like a bubble on the side of a defective automobile tire. If it burst—and it could at any time—Pam would die in minutes. Unfortunately, the aneurysm was located in a place so difficult to access and so close to vital brain functions that normal surgery techniques were too risky; they could cause the rupture that would kill her or inflict permanent brain damage. So her doctor referred her to one of the few places in the world where appropriate surgery might be possible, the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona. Its director, Dr. Robert Spetzler, had developed a new surgical procedure termed hypothermic cardiac arrest. As Sabom (1998, 37) starkly puts it, this procedure would require that “…Pam’s body temperature be lowered to sixty degrees, her heartbeat and breathing stopped, her brain waves flattened, and the blood drained from her head. In everyday terms, she would be dead.”

I must admit that I find just reading about this is a little frightening. It brings back memories for me, as it probably will for many readers, of having surgery, lying on that cold table with an intravenous line inserted. There’s an interesting part then, in my own memories, where I’m having an intellectual conversation with the anesthetist about the nature of anesthesia (it’s a professional interest to me how consciousness can be so altered as to feel no pain, and I’d rather think about my technical interests and competences than about what’s going to happen to me soon on that table!), and suddenly, to my perception, I’m coming back to consciousness in the recovery room, having gone unconscious midsentence, without even feeling sleepy first. Pam remembered intravenous lines being put in, and I’m sure she was much more worried than I, since she had a life-threatening situation.

General anesthesia was begun, and various instruments were connected to Pam’s body to monitor her condition. (I’ve examined Pam’s anesthesia records, courtesy of Dr. Sabom. For us laypeople, we can say that she was very heavily sedated.) Blood pressure and blood flow from her heart were continuously monitored, as well as blood oxygen levels. Temperature sensors were placed in her esophagus and bladder to monitor her core body temperature, and her brain temperature was also monitored. Conventional EEG electrodes on her scalp would measure cortical brain activity, and the auditory nerve center in her brain stem would be monitored. This involved putting molded earphones in both her ears and continuously playing hundred-decibel clicks (the amount of sound that a full symphony orchestra, all playing loudly, can put out, or like being beside a jackhammer—loud!), while looking for an averaged evoked electrical response from this deep brain-stem level.

After about an hour and a half of preparation, Dr. Spetzler began the surgery by opening a flap of scalp, exposing Pam’s skull. The anesthesiologist would have indicated that she was adequately unconscious for doing this. Spetzler then used a bone saw to open her skull. This pneumatically powered saw gave off a loud buzzing noise as it ran.

In her later account to Dr. Sabom (1998, 41), Pam reported: “The next thing I recall was the sound: It was a natural D. As I listened to the sound, I felt it was pulling me out of the top of my head. The further out of my body I got, the more clear the tone became. I had the impression it was like a road, a frequency that you go on….”

Recall that Pam had molded earphones in both ears, effectively blocking outside sound, and hundred-decibel clicks repeating several times a second, but the sound or vibration of the bone saw could have reached her inner ears through direct bone conduction. That she would have or recall any experience with this degree of anesthesia is remarkable, though. Pam goes on (Sabom 1998, 41): “I remember seeing several things in the operating room when I was looking down. It was the most aware that I think that I have ever been in my entire life….” (Note that describing experiences as especially clear isn’t what you normally expect from patients on sedative drugs or nitrous oxide, but this is common in NDEs.)

The account continues (Sabom 1998, 41): “I was metaphorically sitting on Dr. Spetzler’s shoulder. It was not like normal vision. It was brighter and more focused and clearer than normal vision…. There was so much in the operating room that I didn’t recognize, and so many people.”

Over twenty doctors and nurses were present in the operating room, although we don’t know how many of them were present before Pam was anesthetized. Pam goes on (Sabom 1998, 41): “I thought the way they had my head shaved was very peculiar. I expected them to take all of the hair, but they did not.

She then noticed what was making the sound, and described it as looking like an electric toothbrush, with a dent in it and a groove at the top where the saw blade appeared to go into the handle, and also that the saw had interchangeable blades that were stored in what looked like a socket-wrench case. Sabom has sketches of the bone saw and its case for blades in his book, and describing them this way strikes me as quite accurate for a layperson who was trying to make sense of something she was seeing for the first time under what were, to put it mildly, unusual conditions!

While Dr. Spetzler was opening Pam’s head, a female cardiac surgeon had located the femoral artery and vein in Pam’s right groin. But they turned out to be too small to handle the large flow of blood that would be needed to feed the cardiopulmonary bypass machine if the blood had to be drained from Pam’s body, so she got the left-side artery and vein ready for use. Pam later recounted (Sabom 1998, 42): “Someone said something about my veins and arteries being very small. I believe it was a female voice and that it was Dr. Murray, but I’m not sure. She was the cardiologist [sic]. I remember thinking that I should have told her about that….I remember the heart-lung machine. I didn’t like the respirator….I remember a lot of tools and instruments that I did not readily recognize.”

This suggests that Pam’s mind was using psi ability to perceive what was happening in the operating room. She wouldn’t have been able to see anything even had she been conscious, as her eyes were taped shut, nor hear any doctor’s voice because of the molded earphones excluding outside sound and the hundred-decibel clicks masking any really loud sound that did manage to get through. But note that while Pam was heavily anesthetized—certainly deeply enough to feel no pain from the cutting and sawing on her scalp and skull—she was not “dead,” as she would be later. (49)

Dr. Spetzler found, as had been feared, that it was too dangerous to operate directly on the aneurysm, so they would have to induce hypothermic cardiac arrest, that is cool Pam’s body, stop her heart, and drain the blood from her body to keep the aneurysm from bursting. Through tubes inserted into her femoral artery and vein, warm blood was then drawn from Pam and cooled in a special machine.

By 11:00 a.m. her body temperature was down by twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit, and her heart was going into ventricular fibrillation. She was given a massive dose of intravenous potassium chloride to completely stop her heart before the fibrillations could irreversibly damage it. After her heart stopped, her EEG flattened into nothing measureable, and her deeper brain-stem functions, measured by the click stimulation, weakened. By 11:20 a.m. her core body temperature was down to sixty degrees, with her heart still stopped and her brain stem showed no activity. The operating table was tilted up, the blood bypass machine turned off, and the blood drained from her body. By usual medical criteria, Pam was dead.

Pam, meanwhile, was continuing her NDE. She told Dr. Sabom (1998, 43–44): “There was a sensation like being pulled but not against your will. I was going on my own accord, because I wanted to go. I have different metaphors to try to explain this. It was like The Wizard of Oz—being taken up in a tornado vortex, only you’re not spinning around like you’ve got vertigo. You’re very focused and you have a place to go. The feeling was like going up in an elevator real fast. And there was a sensation, but it wasn’t a bodily, physical sensation. It was like a tunnel, but it wasn’t a tunnel.”

This difficulty in finding words adequate to describe the experience is typical of the altered-state aspect of NDEs. New kinds of sensations and experiences can occur that we have no accurate words for and ordinary language wasn’t designed to deal with (Sabom 1998, 44–45):

At some point very early in the tunnel vortex, I became aware of my grandmother calling me. But I didn’t hear her call me with my ears….It was a clearer hearing than with my ears. I trust that sense more than I trust my own ears. The feeling was that she wanted me to come to her, so I continued, with no fear, down the shaft. It’s a dark shaft that I went through, and at the very end, there was this very little, tiny pinpoint of light that kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger.

The light was incredibly bright, like sitting in the middle of a lightbulb. It was so bright that I put my hands in front of my face fully expecting to see them, and I could not. But I knew they were there. Not from a sense of touch. Again, it’s terribly hard to explain, but I knew they were there.

I noticed that as I began to discern different figures in the light—and they were all covered with light; they were light and had light permeating all around them—they began to form shapes I could recognize and understand. I could see that one of them was my grandmother. I don’t know if it was reality or projection, but I would know my grandmother, the sound of her, anytime, anywhere.

Everyone I saw, looking back on it, fit perfectly into my understanding of what that person looked like at their best during their lives.

I recognized a lot of people. My Uncle Gene was there. So was my great-great-Aunt Maggie, who was really a cousin. On Papa’s side of the family, my grandfather was there.…They were specifically taking care of me, looking after me.

They would not permit me to go further….It was communicated to me—that’s the best way I know how to say it, because they didn’t speak like I’m speaking—that if I went all the way into the light, something would happen to me physically. They would be unable to put this “me” back into the body “me,” like I had gone too far and they couldn’t reconnect. So they wouldn’t let me go anywhere or do anything.

I wanted to go into the light, but I also wanted to come back. I had children to be reared. It was like watching a movie on fast-forward on your VCR: you get the general idea, but the individual freeze-frames are not slow enough to get detail.

With no blood in Pam’s body, it was relatively easy for Dr. Spetzler to remove the aneurysm and seal off the artery. Then the blood-bypass machine was turned back on, and warmed blood sent back into her body. Her brain stem and then the higher levels of her brain began to show electrical activity (Sabom 1998, 45): “Then they [Pam’s deceased relatives] were feeding me. They were not doing this through my mouth, like with food, but they were nourishing me with something. The only way I know how to put it is something sparkly. Sparkles is the image that I get. I definitely recall the sensation of being nurtured and being fed and being made strong. I know it sounds funny, because obviously it wasn’t a physical thing, but inside the experience, I felt physically strong, ready for whatever.”

It’s tempting to think that this “feeding” experience corresponded with the warmed blood flowing back into Pam’s body, but we don’t have any precise timing marker in the later parts of her NDE as we seemed to have with her perception of the remark about her veins being too small.

At noon, though, the previously inactive heart monitors showed the disorganized activity of ventricular fibrillation, and it wasn’t corrected with just more warming of her blood. This fibrillation could kill Pam within minutes. Her heart was shocked, without effect, then shocked a second time, which finally restored a normal heart rhythm.

Meanwhile, but again we don’t have markers for precise timing, Pam’s NDE continues (Sabom 1998, 46):

My grandmother didn’t take me back through the tunnel, or even send me back or ask me to go. She just looked up at me. I expected to go with her, but it was communicated to me that she just didn’t think she would do that. My uncle said he would do it. He’s the one who took me back through the end of the tunnel. Everything was fine. I did want to go.

But then I got to the end of it and saw the thing, my body. I didn’t want to get into it….It looked terrible, like a train wreck. It looked like what it was: dead. I believe it was covered. It scared me and I didn’t want to look at it.

It was communicated to me that it was like jumping into a swimming pool. No problem, just jump right into the swimming pool. I didn’t want to, but I guess I was late or something because he [the uncle] pushed me. I felt a definite repelling and at the same time a pulling from the body. The body was pulling and the tunnel was pushing….It was like diving into a pool of ice water….It hurt!

Given that by ordinary criteria, Pam was still heavily anesthetized, one wonders how it could hurt.

By a little after 12:30, Pam was stable enough to be disconnected from the blood-bypass machine. Dr. Spetzler left the operating room, because his younger assistant surgeons normally closed the various surgical wounds. They turned off the classical music Dr. Spetzler usually enjoyed in the background during surgery, and played rock music as background to their task. Pam later told Dr. Sabom that when she came back, they were playing the hit song “Hotel California,” by the Eagles, which has a famous line about how a person can check out but somehow never be able to really leave. Pam felt that this was an amazingly insensitive thing to play in an operating room (Sabom 1998, 47)!

One can argue about the timing in Pam’s NDE—if time in an altered state is experienced more rapidly than in an ordinary state, for example, could her entire NDE have taken place while there was still activity in her living brain, before she was brought to a standstill?—such that her NDE did not really occur while she was technically dead? But that’s an argument that itself pushes a lot of our ideas about what time is, so it certainly looks, by ordinary standards, as if parts of Pam’s NDE happened after she was physically dead.

Essential science likes to collect a lot of evidence about something before getting too serious in theorizing about what might have happened. It would be wonderful if we had more cases like this, but so far we don’t. (50) But let’s do a little theorizing now based on the big five and many maybes we’ve reviewed so far.

Almost all of you who’ve had your own OBEs, NDEs, or both know, on some very deep level, that your mind or soul is something more than your physical body. Our everyday, automatic, psychological identification of who we are with our physical bodies, with the simulation constructed by the ecological self we discussed in chapter 12, is a useful working tool for everyday life but not the final answer. As discussed earlier, though, integrating this experiential knowledge with your ordinary self in the everyday world is not always easy, especially when the too dominant climate of scientism constantly tells you that your deeper knowledge is wrong and that you’re crazy to take it seriously.

My small contribution toward integration is the message that, using the best of essential scientific method rather than scientism, looking factually at all of the data rather than just what fits into a philosophy of physicalism, the facts of reality require a model or theory of who we are and what reality is that takes psi phenomena; OBEs; NDEs; and noetic, ASC knowledge seriously. Certainly we all make mistakes in our thinking at times, but you’re not deluded or crazy to try to integrate this kind of knowledge with the rest of your life. You’re engaged in a real and important process!

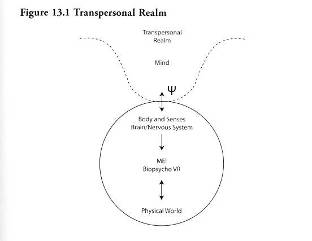

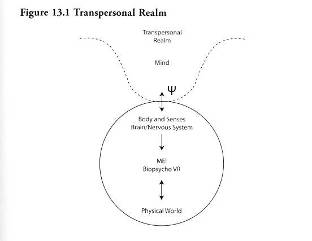

I can schematize my best scientific and personal understanding of our nature at this point with a diagram I created years ago (1993).

Being a product of older Western culture, which makes me think that the spiritual realm is “higher,” I’ve put a transpersonal or spiritual realm at the top of the figure, and I’ve shown it as unbounded in extent. (Perhaps the transpersonal realm should be drawn at the bottom—basis of all, or totally surrounding—nature of all, the rest of the figure, depending on what aspect you want to symbolically represent.) Those of you who’ve had OBEs, NDEs, or other transpersonal experiences know, to some degree, of what realm of experience I speak here, even if ordinary words can’t describe it well. A part of that transpersonal realm, designated as “Mind” in figure 13.1 is in intimate relation with our particular body, brain, and nervous system. As I mentioned briefly earlier, although this “mind” is of a different nature from ordinary matter, I believe that psi phenomena like clairvoyance and PK are the means that link the transpersonal and the physical; that is, our mind has an intimate and ongoing relationship with our body, brain, and nervous system through what I’ve termed auto-clairvoyance, where “mind” reads the physical state of the brain, and auto-PK, where “mind” uses psychokinesis to affect the operation of the physical brain.

The result of this interaction is the creation of a bio-psychological virtual reality, or BPVR, an emergent system labeled “ME!” in the figure, to stand for “Mind Embodied.” The bold type and exclamation point remind us that our identification with and attachment to ME! is almost always intense! We may have lofty philosophical beliefs about how the spirit is so much more than the merely material, but if somebody shoves our head underwater and holds us down, the beliefs and needs of ME! will manifest quite strongly!

This ME! is a simulation, derived from and expressing our ultimate, transpersonal nature, our physical nature, and the external physical world around us. We ordinarily live “inside” this simulation; we identify with it and mistake it for a direct and complete perception of reality and ourselves. But those of you who’ve been “out” in various ways know, as we’ve just discussed, our ordinary self is indeed just a specialized and limited point of view, not the whole of reality.

We need an immense amount of research to fill in the details of this general outline, of course, but I think this conveys a useful general picture.

If you’ve never had an OBE or NDE, dear reader, let me suggest you try to meet someone who has—not someone filled with ideas and convictions based on thinking or emotions, but someone who has actually had the experience and is willing to talk about it.

Here are some of the key points of this wider model of human nature, taken from what we’ve discussed, that will help set the stage for the remaining chapters:

• There’s no doubt that the physics and chemistry of body, brain, and nervous system (the BBNS) are important in affecting and (partially) determining our experience. Further conventional research on these areas is vitally important, especially if it’s done without the traditional scientistic arrogance that physical findings in, for example, neurology automatically “explain away” psychological and experiential data. Sometimes they do; sometimes they don’t, but we have to discriminate which is which.

• The findings of scientific parapsychology force us to pragmatically accept that minds can do things—perform information-gathering processes like telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition (ESP), and directly affect the physical world with PK and psychic healing—that cannot be reduced to physical explanations, given current scientific knowledge or reasonable extensions of it. So it’s vitally important to investigate what minds can do in terms of mind, not faithfully (faithful to dogmatic materialism) wait for these phenomena to be explained (away) someday in terms of brain functioning. The firm belief that they’ll be thus explained away is a form of faith that, as mentioned earlier, philosophers have aptly called “promissory materialism,” and it’s indeed mere faith since it cannot be scientifically refuted. You can never prove that someday everything won’t be explained in terms of a greatly advanced physics—or a greatly advanced knowledge of angels, dowsing, stock market movements, or whatever. Recall that if there’s no way of disproving an idea or theory, you may like it or dislike it, believe it or disbelieve it, but it’s not a scientific theory.

• The kind of research on the nature of mind called for above is vitally important, because most forms of scientism have a psychopathological effect on too many people by denying and invalidating the spiritual or transpersonal longings and experiences that they have. This produces not just unnecessary individual suffering but also attitudes of isolation and cynicism that worsen the state of the world. You can review my Western Creed exercise in chapter 1 for elaborations of this point, and also some of the consequences I would see for my life (and your life) if the Western Creed were true, which I discuss in a later chapter.

• Two of the most important kinds of transpersonal, spiritual experiences people can have are OBEs and NDEs. They have major, long-term effects on the attitudes toward life of those experiencing such phenomena. People experiencing both of these psi phenomena from the inside have what to them is a revelation of a truer or higher understanding of who we really are. While this is usually a positive feeling and psychologically gratifying, it’s also important to extensively investigate these phenomena more deeply, because they themselves may be, at least partially, simulations of even higher-order truths as well as distortions of reality. Remember, just because something feels deeply true does not make it true. The essential scientific approach to such feelings, then, is to take them seriously indeed but to, with humility and dedication, (1) try to get clearer data on their exact nature; (2) develop theories and understandings of them (both in our ordinary state and in appropriate ASCs, along the lines of state-specific sciences that I’ve proposed elsewhere) (1972, 1998a); (3) predict and test consequences of these theories; and (4) honestly and fully communicate all parts of this process of investigation, theorizing, and prediction.

Genuine and open scientific inquiry has much to contribute to our understanding of our spiritual nature.