Chapter 15

Experimental Approach to Postmortem Survival

* * *

MEDIUM (origin: Latin, literally “middle,” “midst”): (1) A person acting as an intermediary, a mediator, rare. (2) (Plural: “-iums”) A person thought to be in contact with the spirits of the dead and to communicate between the living and the dead.

MEDIUMSHIP (noun): (1) The state or condition of being or acting as a spiritualistic medium; (2) intervening agency, intermediation.—Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “medium” and “mediumship”

* * *

The most direct kind of evidence bearing on possible postmortem survival comes from studies with spiritualist mediums. A medium is someone who believes she can serve as an intermediary to convey messages to and from whatever aspect of people survives death, usually in a special session termed a séance. We know far less about the psychology of mediumship than we need to, but there’s a lot of variation in how it’s done. In the classical days of studying mediumship (mid and late 1800s through early and middle 1900s), the most interesting mediums went into “trances,” ASCs of which they usually remembered nothing after coming back to normal, but during which they believed they were temporarily “possessed” or controlled by a guiding spirit who controlled access by other spirits, deceased spirits, or both so that they could perform their role as a communications medium. Such deep-trance mediums are rarer nowadays, and contemporary mediums usually remain in pretty much an ordinary state of consciousness while getting impressions (visual and auditory images) of what the deceased spirits want to communicate.

There have always been people like this in all human societies that we know of, often playing a central role in the societies’ religious systems. Christian culture deliberately suppressed such people, calling mediumship and related areas the “work of the devil,” and more-modern psychiatric diagnoses of it as inherently pathological further suppresses it. Who wants to be regarded as crazy? There may be a lot of people around with a natural talent for mediumship who are thus inhibited from developing it.

In its present Western form, mediumship began in December 1847, in Hydesville, New York. Three sisters, two of them still teenagers, Margaret, Leah, and Kate Fox, heard strange rapping sounds that seemed to come from the walls. Soon neighbors visited to hear the sounds, and by using a code of various numbers of raps for yes or no, apparent communication with deceased spirits occurred. The story of what happened to the Fox sisters over their lives is fascinating and complicated (Weisberg 2005), especially as to whether a “confession” that Margaret had faked it all, obtained from one sister but later repudiated, was the real truth or a desperate sellout for money from an old, destitute, and, by then, alcoholic woman. What matters to us is that those 1847 raps fed into religious yearning and inspired social movements in America and then Europe, which rapidly led to Spiritualism’s becoming a major (and always highly controversial) religious movement.

At its best, Spiritualism had (and still has) an attitude quite congruent with essential science. Like the science of its time (and today), it recognized that a lot of received religious beliefs had been shown to be false by science. Beliefs, like scientific theories, should, as much as possible, be based on evidence, not unrecognized emotions or hopes and fears. So Spiritualists didn’t ask anyone to believe in postmortem survival or what the spirits communicated and taught. They asked, quite reasonably, that you consider the possibility that there might be such survival and then look at the evidence for it. Go to a good medium, they would say, ask her (mediums are of both sexes, but women usually predominated) to contact a deceased relative or friend, and then ask that ostensible spirit sufficient questions to establish whether he is or isn’t who he claims to be. Perfection wasn’t expected, because the communication channel of the medium was recognized as noisy and as distorting transmission sometimes, like a poor, long-distance telephone or cell-phone connection, and the spirits themselves often complained that they could not get their messages across accurately. But if there were lots of good answers, then you could believe that this was indeed the spirit of your deceased relative. If not, you certainly shouldn’t believe it.

Another aspect was physical mediumship, where spirits apparently proved their existence by performing psychokinetic feats, such as levitating tables, speaking aloud from midair, and so on, but this is a very complex area, sometimes involving deliberate fraud, and we won’t go into it here, because the evidence for survival it produced wasn’t as direct as the information from ostensible spirits. D. D. Home, discussed in chapter 9, was an example of an outstanding physical medium.

Of course, what evolved, Spiritualism as an organized religion, has added, like any human activity, a great deal of accumulated belief that may overshadow this basic scientific, investigative function.

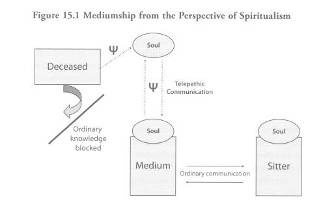

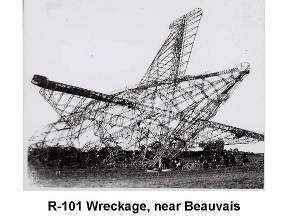

Figure 15.1 diagrams how mediumship is theorized to work according to general Spiritualist beliefs.

The medium and the person seeking communication, the sitter, are together communicating via their physical bodies and senses, the sitter asking questions or responding to the medium’s statements, and the medium supposedly communicating what the spirits are telling her. That’s at the ordinary, material level. At a mind or soul level, though, the medium’s soul is using some kind of telepathy to communicate with the soul of the departed spirit. Ordinary knowledge about the deceased is blocked, the deflected arrow in the figure, since ideally the medium didn’t know the deceased or have access to any ordinary knowledge about him.

The materialist’s model of mediumship rules out any possibility of postmortem survival of any aspect of consciousness, of course, as well as psi ability in general. It could be represented in figure 15.2.

Here the deceased is simply gone, and there are no souls of the deceased, the medium, or the sitter to engage in any kind of communication. If there’s any resemblance between the deceased’s qualities and what the medium says, we must attribute it to some combination of deliberate, conscious fraud on the medium’s part, coincidence, conscious or unconscious cold reading by the medium as some part of her mind imitates the deceased, or all of these. “Cold reading” (Nelson 1971) is the technical term used by magician mentalists and fraudulent psychics to mean ways of faking a psychic reading, based on close observation of physical characteristics of the sitter and her responses to leading questions.

I haven’t personally investigated mediumship in an active way but have, rather, contented myself with extensive reading of and thinking about my colleagues’ studies. Why not look into it personally? Partly I’ve simply been too busy with my many other interests, and partly I’ve recognized what a complex area it is and that I’d have to give up too many of my other interests to get adequately involved in mediumship studies; it may be partly temperament or because I have little interest in the future, being content to take life as it comes. Who knows why? Perhaps I have some unacknowledged fear of death that I subconsciously deal with by avoiding too close contact with mediums? But here I’ll sketch the picture of what fairly extensive evidence collected by others shows.

The most solid finding that I think all investigators who try to be objective and scientific would agree on is that the results of most mediumistic séances do not provide strong evidence for (or against) survival. Almost all séances are held to provide comfort to the bereaved; they usually do this, and it’s an important psychological function. Bereaved people may want evidence that a loved one has survived and is continuing a happy existence, but emotional need makes them poor judges of evidence. If the sitter asks the medium to contact Uncle Joe, for instance, and Uncle Joe “proves” his identity to the sitter by telling him, “You know I always loved you, even when I couldn’t show it very well,” that may be emotionally convincing to the bereaved sitter and may perhaps even be true, but it won’t impress others. It’s far too vague and general.

Just as in the evaluation of descriptive statements about distant target locations in remote-viewing experiments, discussed in chapter 7, for significance we need correct and specific statements about the intended targets without a lot of generalities that apply to many other targets diluting them. (The blind judging and statistical evaluation techniques developed for remote viewing would be excellent for studying mediumship, but very little has been done so far.) A nonemotionally involved observer will want the Uncle Joes of séances to produce specific, verifiable facts particular to their earthly lives, specific facts that wouldn’t be known to the mediums through normal means, or readily deduced from the appearances or actions of the sitters. And deliberate fraud must be ruled out. Like any area of human activity where money and power can be gained, there are many who prey on others, ranging from the mild forms of “cold readings” to impress the bereaved with psychological trickery based on sensory observations and psychological manipulations, to serious swindling schemes where private detectives track down information about deceased relatives to make the faked communications from the spirits look genuine, so when substantial “donations” are asked for, they’re likely to be gotten (Keene 1976).

But there have been many honest and outstanding mediums who’ve given much more impressive results than vague generalities to comfort the bereaved. I’ll give two examples here to illustrate both the richness and the complexity of this material.

I had the privilege of meeting Eileen J. Garrett (1893–1970), one of the world’s outstanding mediums, while I was still an engineering student at MIT, back in 1955 and 1956. She lectured several times in Boston, and I was invited to small receptions with her afterward. While she’d been a medium most of her life, she was also honestly puzzled and curious about what she did and, through her Parapsychology Foundation, was a major supporter of research in parapsychology.

Mrs. Garrett was investigated by several researchers and was familiar with all the attempts to explain mediumship, both pro and con. When asked, toward the end of her life, whether she believed that she really communicated with spirits, she replied that on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays she was certain of it. On Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, though, she thought that the psychologists were probably right, that it was just her unconscious mind making it up, with a little ESP thrown in for veracity. On Sundays she didn’t give a damn!

The Challenger Disaster of Its Time

In 1930, Mrs. Garrett was unexpectedly involved in a very impressive mediumship case. She lived in London at the time, and all of Britain had been excited for months over the forthcoming launch of a new dirigible, the R-101, by the British military. There was controversy, too, as some people thought the airship hadn’t been tested enough, and both Mrs. Garrett and some other psychics had experienced warnings that there would be some kind of disaster. She gave a personal warning of these predictions she’d received through her spirit control, while in trance, to Sir Sefton Brankner, director of civil aviation at the Air Ministry, more than two weeks before the airship’s scheduled departure. His answer was, “We are committed.” The flight had to be made, for prestige purposes, before the October Imperial Conference of Dominion Prime Ministers. Naturally, the government didn’t pay attention to warnings from psychics!

The excitement then was comparable to our excitement at the beginning of the first manned launches into space. This giant airship was to be a triumph of technology, introducing a way of flying from Britain to India instead of the long sea voyage.

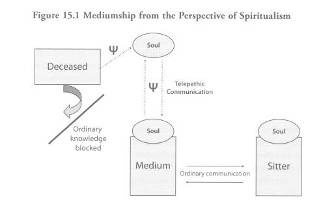

Figure 15.3 R-101 Airship

The R-101 left Cardington Aerodrome as scheduled at 7:36 p.m. on October 4, 1930, bound for India. At 2:05 a.m. that night, she crashed into a hill in France and exploded. Forty-eight people died in the crash. One of those who died was the wife of Sir Sefton Brankner. The world was shocked, and grieved! Its effect on people was comparable to the U.S. 1986 Challenger space-shuttle disaster.

Figure 15.4 R-101 Airship Crashed

Three days later, October 7, an already scheduled séance was held for a visiting Australian journalist, Ian Coster, and British psychical researcher Harry Price. The prearranged aim was to try to contact Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the Sherlock Holmes detective stories, who’d died three months before. An expert stenographer noted everything that was said.

Mrs. Garrett went into her usual trance, with her usual control spirit, Uvani, working through her, and was working on contacting Doyle, when suddenly (Fuller 1979, 224):

…Eileen became agitated. Tears rolled down her cheeks. Her hands clenched. Uvani’s voice became hurrying. “I see I-R-V-I-N-G or I-R-V-I-N. [Flight Lieutenant H. C. Irwin was captain of the R-101.] He says he must do something about it. Apologizes for interfering. For heaven’s sake, give this to them. The whole bulk of the dirigible was too much for her engine capacity. Engines too heavy.…Gross lift computed badly. And this idea of new elevators totally mad. Elevator jammed. Oil pipe plugged [more technical details].…Almost scraped the roofs at Achy.”

Achy was an obscure railroad junction in France, not shown on regular maps, but it was on dirigible navigation maps.

The following is from notes reconstructed the day after another session, with Major Oliver G. Villiers, an Air Ministry Intelligence officer (Fuller 1979, 251):

Communicator Irwin: “One of the struts in the nose collapsed and caused a tear in the cover. It is the same strut that caused trouble before and they know…(sitter believes reference was to officials in Air Ministry). The wind was blowing hard, and it was raining. The rush of wind caused the first dive. And then we straightened out again. And another gust surging through the hole finished us.”

Sitter Villiers: “Tell me, what caused the explosion?”

Communicator Irwin: “The diesel engine had been backfiring because the oil feed was not right. You see the pressure in some of the gas bags was accentuated by the undergirders crumpling up. The extra pressure pushed the gas out. And at that moment the engine backfired and ignited the escaping gas.”

In a somewhat amusing aftermath once this material was published, two Royal Air Force Intelligence officers came to interview Garrett. It turned out that they suspected Garrett of having had an affair with one of the R-101’s officers: there were too many correct but militarily classified technical details in her account!

As to these technical details, Mrs. Garrett’s granddaughter, Lisette Coly, assures me that Mrs. Garrett was not at all a technical type of person; it was hard for her to operate a TV set without help. Andrew MacKenzie (1980) also notes that it’s usually quite difficult to get technical details in mediumistic sittings.

In this R-101 example of high-quality, mediumistic communications, we have plenty of specific detail, correct for the particular situation and not likely accessible by ordinary means. Let’s look at another high-quality case that will further illustrate both the possible quality of mediumistic readings and their complexities. This case is from the personal experience of Rosalind Heywood (1964), a British psychic investigator:

After the war I went to a Scottish medium to see if she could pick up something about a friend, a German diplomat whom I feared had been killed either by the Nazis or the Russians. I simply didn’t know what had happened to him. The medium very soon got onto him. She gave his Christian name, talked about things we had done together in Washington, and described correctly my opinion of his character. She said he was dead and that his death was so tragic he didn’t want to talk about it. She gave a number of striking details about him and the evidence of personality was very strong….

Who wouldn’t be impressed with this kind of material? Indeed, many investigators say evidence of personality, little quirks about a communicator that embody the deceased’s style, can often be more impressive than simple factual data.

However, Heywood goes on (1964 as quoted in Roll 1985, 178–79):

If I had never heard any more, I would have thought it very impressive. But after the sitting, I set about trying to find out something about him. Finally the Swiss foreign office found him for me. He was not dead. He had escaped from Germany and had married an English girl. He wrote to me that he had never been so happy in his life. So there I think the medium was reading my expectations. She was quite wrong about the actual facts but quite right according to what I had expected.

There are no exact statistics on the occurrence of mediumistic communications that are impressive in terms of apparent psi elements but quite incorrect about the person’s being dead. The impression of a number of my colleagues is that these cases are uncommon but not extremely rare. That this sort of thing can happen at all, though, means that we must theorize that, in at least some, if not all, cases, there might not be any actual postmortem survival but, rather, that the high-quality evidence can be alternatively explained by a theory of unconscious impersonation plus unconscious psi phenomena. That is, some aspect of the unconscious mind of the medium imitates the deceased and, in addition to generalities and pleasantries that make the sitter feel good, adds occasional veridical information obtained by psi ability. Since this veridical information is often extensive and highly specific, compared to the statistically significant, but practically tiny, amounts of psi ability seen in most laboratory studies, this kind of psi phenomena is referred to as super-psi phenomena.

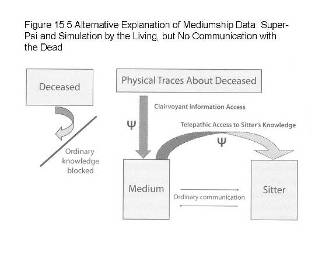

Figure 15.5 diagrams the unconscious impersonation plus super-psi theory as an alternative explanation of what happens in good mediumship. By some combination of unconscious clairvoyance of physical traces of information about the deceased, plus telepathic access to the sitter’s (and other people’s) knowledge about the deceased, a plausible simulation of a surviving spirit is constructed.

This is a rather amazing alternative theory if you think about it. Unconscious impersonation, unconscious use of psi ability, and high-level super-psi ability: how plausible is it?

Unconscious impersonation of another personality is a generally accepted psychological phenomenon. When I was extensively involved in hypnosis research at Stanford University back in the 1960s, for instance, one of the standard items on our regular hypnotic susceptibility scale for talented subjects included such a suggestion, and stage hypnotists often amuse audiences by picking some obviously shy-looking volunteers from the audience, subtly selected among them for those having high hypnotic talent, hypnotizing them, and then suggesting that they’re a famous rock star or similar performer. The theatrical, extroverted performances as they sing are usually pretty impressive! This kind of thing is routine for stage hypnotists, so the idea of unconscious impersonation by mediums is plausible. In our cultural setting, this is “obviously” a demonstration of hypnosis and the powers of the unconscious mind. In other cultural settings, this sort of thing might be an “obvious” example of “spirit” possession.

How about unconscious use of psi ability? How plausible is that? In a general way, unconscious use of psi ability has been demonstrated repeatedly for decades in parapsychological experiments as the sheep-goat effect, introduced in chapter 8. This effect, discovered by psychologist Gertrude Schmeidler in 1942, is unusual and important enough to discuss in further detail. A multiple-choice ESP test, such as a card-guessing test, telepathic or clairvoyant, is given to a group of percipients. Before the actual ESP test, they fill out a questionnaire asking, among other things, about their belief in ESP or their personal ESP abilities. The sheep are those who believe in ESP, the goats those who don’t.

The ESP test is given, its results recorded and then scored separately for the sheep and the goats. The sheep usually score above chance expectation, often significantly so. The goats, in contrast, usually score below chance expectation, often significantly so.

Almost all of these sheep-goat studies have been done with highly educated people, usually college students. There’s a belief implicitly drummed into us over and over again through our schooling by its repeated occurrence: tests measure what you know. The more you know, the higher your test scores; the less you know, the lower. They wouldn’t give us all those tests unless it meant something, would they?

The sheep believe in ESP: they take a test to measure ESP, tend to get a “good,” above-chance score, and therefore are happy. They’re good sheep, properly herded by their shepherd, the experimenter. Their beliefs have been confirmed: there is ESP and their scores showed it. The goats, on the other hand, the stubborn ones not following the shepherd’s leadership, don’t believe in ESP, there’s nothing to be measured on the test, and sure enough, they get low scores, which seems to verify their beliefs that there’s indeed nothing to measure. Everybody who believes that tests measure what you know is happy.

Of course, these aren’t statistically sophisticated people who realize that below-chance scoring can be just as significant as above-chance scoring. I don’t believe anyone has ever done a sheep-goat experiment with statistically sophisticated people. (52)

So how do you score significantly below chance? The only possible way I’ve ever thought of or heard anyone else mention is that while you’re undoubtedly just guessing most of the time, every once in a while you unconsciously use some form of ESP to correctly know what the next test card is, and then your unconscious mind influences your conscious mind to guess anything but that correct answer.

I find this a marvelous demonstration of the power of the human mind: we can unconsciously use ESP in the service of our needs, in this case to support our belief that there is no ESP! Our clever minds (mistakenly) produce a “miracle” to demonstrate that there are no miracles!

Returning to the super-psi hypothesis as an alternative explanation for accurate mediumistic results, the answer is yes; it is plausible that, at least occasionally, a medium, believing in spirit survival, might unconsciously use psi ability to get valid information that increases the believability of her unconscious imitation of a deceased person.

Sometimes I wonder about the place of unconscious, unrecognized psi ability in life. When we think about the long-term possibilities of investigating spirituality and add psi phenomena into the equation, you can see that these kind of results, while arguing for some kind of reality to spirituality in a general sense, also mean that those future investigations may require a lot of sophistication if people can unconsciously use psi ability to support the particulars of their belief systems.

Here’s another example of unconsciously using psi ability in support of our needs. Parapsychologist Rex Stanford thought about people who were “lucky.” What exactly did being “lucky” mean? Some events attributed to luck are really the deliberate use, consciously or unconsciously, of skills; it’s just not obvious to us how this was done. And clearly some luck is just coincidence; a person just happens to be in the right place at the right time for something good to happen. Yet it often seems that some people are persistently lucky rather than that instances of good luck are uniformly spread across the population.

Stanford devised a theory of psi-mediated instrumental responses (PMIRs) (1974), and he and his colleagues carried out a number of experiments to test his theory that at least sometimes, we unconsciously use psi ability to scan our world, detect a situation coming up that it would be lucky to be involved in (or avoid), and our unconscious influences our conscious mind to just happen to be at the right place at the right time. Being at the right place at the right time is the instrumental (effective) response in psychological jargon. The person manifesting the PMIR has no idea she’s using psi ability in this way; for example, she suddenly feels like taking a walk around the block and “just happens” to meet a person who does something that benefits her. Indeed she can be a person who doesn’t believe in weird things like psi ability, yet still benefits from her unconscious, instrumental use of it.

Stanford and his colleagues conducted several studies of potential PMIRs, and in one (Stanford et al. 1976), forty college-age men were individually tested by an attractive female experimenter. No mention of the PMIR hypothesis was made to these percipients. Each person participated in a short word-association test; the experimenter would say a word from a list and the percipient would respond with the first word that came to his mind. The experimenter recorded the time it took the percipient to make each response. To all appearances, this was a straightforward psychology experiment of a kind that had been done hundreds of times before in mainstream psychology.

None of the percipients knew that there was a sealed decision sheet (a different one for each of them) on which one of the words of the association list had been randomly selected as a psi target. For half (randomly selected) of the men, if their fastest (or tied for fastest) response was the target word, they would go on to participate in a much more interesting ESP experiment after the word-association test was finished. The other half of the group had to give their slowest (or tied for slowest) response for the key word. Stanford believed that this wouldn’t work as well because he theorized it would be easier for psi ability to speed up a response on such a test than to inhibit one.

The experimenter giving the association test did not, of course, know what the key word was until the test was completed, so she couldn’t make biased scoring errors. The percipients had no idea (by ordinary means) that their responses in the first part of this experiment would affect what happened in the second part, or even that there would be a second part to the experiment.

The favorable experiment consisted of participating in a picture-perception ESP task under pleasant, relaxed conditions, with positive suggestions. The female experimenter conducted this task, which would presumably be quite pleasant to the male percipients. The less interesting experiment consisted of sitting alone in a straight-backed chair in the experimental room doing card-guessing tests for twenty-five minutes. (I’ve always wondered what it said about the psychology of many classical parapsychology experiments that this kind of card-guessing test was used as a kind of punishment.)

The results supported Stanford’s PMIR hypothesis. In the fast group, the correct associations occurred significantly faster than they would by chance. As expected, the speed increase in the fast-response condition was larger than the speed decrease in the slow-response condition.

In the favorable second experiment of another PMIR study (Stanford et al. 1976), college-age men participated in a picture-rating task of attractiveness showing college-age women in varying degrees of undress. In the unfavorable condition, they participated in a vigilance task with a pursuit rotor. This was a device developed in the early days of psychology to measure motor skill. You had to hold a stylus over a small patch of light on the pursuit rotor (a rotating disk), but it was set to rotate at such a slow speed that the task was very easy, unskilled, very boring, and physically tiring. The percipient had to keep this up for twenty-five minutes. Again, word-association times were significantly changed.

So we have good evidence that two of the three aspects of the alternative theory, unconscious impersonation and unconscious use of psi ability, can happen in other situations. Whether this happens rarely, often, or always in mediumship is still a wide-open question.

The third aspect of this alternative theory, the “super” in super-psi ability, creates big problems though. If you really make the possible psi ability super, able to pull out large amounts of specifically correct information, you not only require much larger amounts of psi ability than living percipients usually show when they deliberately try to use psi ability in various laboratory tests, you also get beyond the limits of science. Recall that when we discussed essential scientific method in chapter 2, one of the characteristics of a scientific theory was that, in principle, it was disprovable; that is, it could logically lead to predictions of outcomes that, when tested, did not occur, and so the theory could be rejected. When you vaguely allow psi ability to be super, though, when you have no limits on what it might do, you can’t disprove it. If we allow super-psi ability, for example, we might say that right now you’re mistaken in thinking that you’re sitting in a chair reading this book. Actually you’re long dead, with no physical body and no location in the material world; you’re just unconsciously hallucinating this world and using various forms of super-psi ability to create an ongoing, consistent hallucination of being embodied and reading this book. With no limits on your unconscious, psychic abilities, how could you disprove that?

For those who like clear, neat, and tidy outcomes of their research, the super-psi explanation of mediumship results is a great disincentive to bother doing research. With a few major exceptions, such as psychologist Gary Schwartz’s recent ingenious work at the University of Arizona (2003), and intermittent work under the auspices of the Society for Psychical Research in England, for example, the fascinating work on physical mediumship of the Scole group (Keen, Ellison, and Fontana 1999), there’s little research on survival via investigation of mediumship going on today. Almost all of what we know comes from the older research. Why did it die out (no pun intended)?

Primarily, of course, in the mainstream scientistic world, postmortem survival research is a taboo topic. The mind is nothing but the brain, which turns to mush when we die; survival is thus a priori impossible, so only fools, charlatans, and crazies would want to research it.

The world of psychical research, where the mediumship work took place, was (and still is, unfortunately) a very small world, with almost no full-time, trained scientific researchers and only a few dozen part-timers like me. Resources are extremely limited, and most of the part-timers, like me, tend to be scholars who study the older work rather than active researchers. And conceptually, as noted previously, the super-psi hypothesis to explain mediumship put a lot of inhibition on the motivation to study postmortem survival. Why collect more evidence for survival when it not only might be nothing but unconscious impersonations plus super-psi ability but when you also can’t figure out a way to distinguish the two?

Personally I’m not too bothered by an alternative, super-psi explanation of the good mediumship evidence. A creature who can use super-psi ability actually sounds like the kind of creature who’s not so dependent on his or her physical body and thus might survive death. Such a creature might even be described as spiritual.