Chapter 16

* * *

REINCARNATION (mid nineteenth century [origin: from “re-“ plus “incarnation”]): (1) Renewed incarnation, especially (in some beliefs) the rebirth of a soul in a new body. (2) A fresh embodiment of a person. —Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 6th ed., s.v. “reincarnation”

* * *

Reincarnation or rebirth is the belief, held by a large proportion of the world’s population, that some essential aspect of one’s living self, the soul, survives physical death and, after some period of varying length in an afterlife state, is reborn as the soul of a new being. Beliefs in reincarnation usually include a belief in some form of karma, a psychic law of cause and effect, so that actions in one lifetime will eventually, when circumstances are ripe, have effects in a later lifetime. In classical Hinduism and Buddhism, for example, a person who performs virtuous actions and grows spiritually in one life is more likely to be reborn in happy circumstances and have good things happen to her as she interacts with others. Someone who lived an evil life, on the other hand, is likely to be reborn in difficult circumstances or even, in some belief systems, as an animal or other kind of being.

The typical flavor that comes with belief in reincarnation in the East is negative: you suffer in this life, and unless you get enlightened, you’ll suffer in future lives as your karma ripens, you unskillfully generate more negative karma, or both. My own bias, what I’d like to be true, as a Westerner believing in progress, is positive: there’s so much to learn in life, so many interesting things, that one lifetime isn’t anywhere near enough to make much progress on this. So I look forward to returning to “school” many times until I finally have a “master’s degree.” That’s just my personal bias, of course, which has no bearing on the important question as to whether reincarnation is real. Remember, as a scientist my strong desire is to know the truth, whether or not it accords with what I’d like it to be. Part of having a better chance of learning the truth is to know what biases you have in approaching issues.

If reincarnation is established for any cases, then we can someday deal with more refined questions like these: Does it happen to everybody or just to some? Does karma actually work? If so, how? How would I live my life more effectively and with a longer-term view if I thought reincarnation was likely? Meanwhile, our basic task remains to assess what evidence we have for reincarnation rather than just blindly believe or disbelieve in it.

Although I’d read about apparent cases of reincarnation that had some evidential value while I was still a teenager, devouring what literature I could find on psychical research and parapsychology, my first serious involvement with a case occurred in fall 1956, while I was a student at MIT. I was browsing in the student bookstore one day. Because I had very little money for anything but essentials, most of my browsing was done at the remaindered books table, and I found one hardcover book for a dollar that intrigued me, The Search for Bridey Murphy, by Morey Bernstein (1956). The title didn’t attract me, and I don’t know why I picked it up and looked at it more closely, because it sounded like some kind of novel. But I saw from the jacket that it was about hypnosis and reincarnation, and since I’d already read extensively about hypnosis, I was intrigued and gambled my dollar.

It was a good gamble, because I ended up fascinated with the story and felt that the whole thing had been well researched. I little suspected, as did the publishers, that the book I’d found being remaindered on the dollar table would soon become a best seller!

Morey Bernstein, the author, was a prominent Colorado businessman who experimented with hypnosis as a hobby. An “amateur hypnotist,” in the sense that he wasn’t trained in psychology or medicine and didn’t charge for what he did, he had a decade of experience using hypnosis in a variety of ways, and I could tell from my own reading that he was quite knowledgeable about the scientific literature on hypnosis. Bernstein had become interested in hypnotic regression, where you suggest to a hypnotized subject that it’s much earlier in time than the present, the subject’s fifth birthday, for example, and often find the subject, especially if she’s hypnotically talented, then beginning to speak and behave like her earlier self. Often the subject talks about things long forgotten, making you wonder if hypnosis can increase memory in a dramatic way.

Bernstein had heard stories of people being regressed to previous lives but was quite skeptical about them. He finally tried it himself, arranging to have six recorded sessions over the course of several months with a casual social acquaintance who was a talented hypnotic subject to whom he gave the pseudonym Ruth Mills Simmons. She was later identified by the press as Virginia Burns Tighe.

I’ll now briefly summarize the case, not to prove or disprove the reality of reincarnation—that would take many books in and of itself to begin to adequately weigh the evidence—but to give the flavor of this kind of material.

I’d read the Bernstein book and put it aside, thinking it definitely provided some good evidence for reincarnation but, like any real case, had possible flaws and questionable points. A while later, I had to reread it though, for the book had hit the best-seller lists and so much was being written about it. Yet what was being written really puzzled me; so much was on the order of “Bernstein made this (ridiculous) claim and that (ridiculous) claim.” I didn’t remember those claims, so I had to check my memory of the book.

This was a great lesson for me about resistance to knowledge, for it soon became clear that the very idea of reincarnation was so upsetting to many people in the culture of the fifties that they lost what sense they had and got kind of crazy! This was even true for writings by people I had regarded, based on their previous published work, as scientific authorities on hypnosis: they made fools of themselves in the course of criticizing and ridiculing Bernstein over things he hadn’t said! In retrospect, I saw that it was a good lesson for a young man to start getting skeptical of authorities, but it was quite shocking to me at the time that people who were supposed to be paragons of truthfulness and accuracy could be so far off.

The discrepancy between what Bernstein had written and claimed (quite modest claims, really) and what was attributed to him and attacked was so great that I’ve somewhat jokingly expressed it as the idea that there must’ve been two books called The Search for Bridey Murphy written by authors named Morey Bernstein and published at about the same time. Clearly I’d read only one of them, and the raging debunkers, the pseudoskeptics, had read the other.

To my pleasure and edification, I met Morey Bernstein and his wife Hazel a few months later when I worked in parapsychology research at physician Andrija Puharich’s Round Table Foundation in summer 1957. It saddened me to hear the inside story of just how vicious and personal so many of the attacks on the book and its author were. Bernstein was especially angry at a Chicago paper that claimed that Virginia Tighe actually spent a lot of time as a child with a neighbor who was Irish and had regaled her with tales of Ireland. According to Bernstein, the neighbor, who never made herself available to be interviewed by any other investigators, was the mother of the publisher of a newspaper whose editor was very angry at Bernstein for not giving his paper early rights to the story, and had told Bernstein he would get back at him!

So what was all the fuss about? Neither Morey Bernstein nor Virginia Tighe had ever visited Ireland, but when she was told to go back to a life before this one, Virginia started to recount memories of a life in which she was named Bridey (Bridget) Kathleen Murphy. She was an Irish girl who claimed to have been born in Cork, Ireland, in 1798. Her father was a Protestant Cork barrister named Duncan Murphy, and her mother was named Kathleen.

Virginia, speaking with an Irish accent, reported that she’d gone to a school run by a Mrs. Strayne and that she had a brother, Duncan Blaine Murphy, who eventually married Mrs. Strayne’s daughter, Aimee Strayne. Bridey also had another brother, but as was too common in those days, he died while still a baby.

When she was twenty, Bridey recounted getting married in a Protestant ceremony to a Catholic, one Brian Joseph McCarthy, the son of another Cork barrister. The couple then moved to Belfast, where her husband received more schooling and, Bridey claimed, eventually taught courses in law at Queens University.

Protestantism versus Catholicism was an issue of great importance then (and today) in Ireland, so the couple married again in a second ceremony by a Catholic priest, Father John Joseph Gorman, of Saint Theresa’s church. Bridey and Brian had no children.

Bridey lived, Virginia recalled, to age sixty-six and then was, to use her own expression, “ditched”—that is, buried—in Belfast in 1964.

Virginia made many statements, some about commonplace things that anyone would know about Ireland, some uncheckable, some found to be incorrect, and some correct and unlikely to be known by most people (Ducasse 1960, 5).

Evaluating a case like this is much more complex (and interesting!) than the laboratory studies described earlier, which established the existence of the five major kinds of psi ability: telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition, psychokinesis, and psychic healing. We can’t come up with some precise mathematical statement that the odds our results are due to chance are one in ten (which we’d regard as no evidence), one in twenty (the traditional level in psychology at which the results are considered “significant,” unlikely to be due to chance), or even less probable. What is “chance” in a case like this? Certainly that an Irishwoman would be named Murphy is not at all improbable, but suppose the term “ditched” for being buried, certainly not in use in America or Ireland at the time of the experiments, turns out to be true (as it did)? How significant is that? Or when, while regressed, she sneezed once and spontaneously asked for a “linen,” how likely is coincidence when you find out that “linen” was a term used for handkerchief way back then? How do you evaluate the fact that evidence can be found for her claimed husband’s existence as a clerk but not as a barrister, so perhaps she was actually recalling a past life but inflating her social status in a way that might’ve been typical in such a past life? Or is this just an example of imagination and it’s only the desire to believe that makes some people see this kind of thing as evidential?

I recommend reading The Search for Bridey Murphy for those interested in reincarnation, for the wealth of detail we have no space to go into here. There’s still a recording available of some of the sessions; as we discussed in the case of mediumship, the style of communications can sometimes seem more evidential than the “facts” involved. When you weigh all the information about Bridey Murphy, I think the rational conclusion is that the evidence it provides for possible reincarnation is strong enough that it would be foolish to just disregard it because of a priori convictions that reincarnation can’t be possible, but it would also be foolish to feel that it “proves” the reality of reincarnation.

This case also illustrates a general problem in investigating reincarnation with modern people: by the time we’re adults or even teenagers, we’ve been exposed to an enormous amount of information about the past. Just as the unconscious impersonation theory of mediumship has been put forward as an alternative to believing that spirits survive death (perhaps with a bit of psi ability, if not super-psi ability, to add verisimilitude to the simulation), perhaps an adult recalling a previous incarnation is simply believing a simulation, a kind of dream, concocted by his unconscious mind.

When hypnotic regression is involved—and many techniques for recalling past lives that aren’t formally called “hypnosis” may indeed be a kind of hypnosis—we must remember that, in general, hypnotized subjects have a great desire to please the hypnotist. Thus when there’s a suggestion that a person will remember a time before her birth, from a previous life, it’s quite reasonable to assume that, at least some of the time, the material “recalled” is actually a fabrication by her unconscious mind. But this is a “fabrication” that seems quite true to the subject; there’s no conscious imagination or lying involved. The recaller has no conscious memory of having read the books or seen the documentaries about past times that provide convincing evidence, but he might have done so; it’s hard to prove someone has never been exposed to certain kinds of material.

For example, I recall a fascinating case reported by psychiatrist Ian Stevenson (1983) in which a Mrs. Crowson (pseudonym) participated in Ouija board séances with a friend, resting one hand on the movable planchette, and thus capable of (unconsciously) influencing it. A lot of excellent, fact-filled communications were received from ostensibly deceased persons, and the details were easily verified in the obituary columns of the London Daily Telegraph. In fact, the material was almost exclusively what you could find in the obituaries, causing Stevenson to wonder if Mrs. Crowson had read them, even if she’d consciously forgotten that she’d done so. She did not read the paper, but her husband read it and also did the crossword puzzles in it, which were on the same page, such that when the paper was folded for convenience in doing the puzzles, there were obituaries visible around it. Mrs. Crowson sometimes finished off crossword puzzles her husband had been unable to complete, so she was visually exposed to the relevant material even if she didn’t consciously look at it. Thus cryptomnesia (concealed recollection, or hidden memory) was the likely normal explanation rather than communication from the deceased.

My own best guess at present is that if you have a hundred cases of past-life recall in adults, by whatever method, there might be some genuine cases among them, but probably some are indeed unconscious fabrications. I wish we had the data to specify what “some” means here, but we don’t.

One partial way around the problem of adults unconsciously knowing so much about the past and being motivated, especially when hypnosis is involved, to please the hypnotist or reincarnation investigator, is to look for instances of young children who spontaneously recall past-life material. While we may not be absolutely certain, we can often be much surer about whether a child has been exposed to certain kinds of factual material compared to an adult.

Psychiatrist Ian Stevenson devoted a major part of his career to looking for and investigating such cases of children who spontaneously claimed to remember past lives, and the laboratory he left behind at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, after his recent death in 2007, now has thousands of such cases. This allows for broadscale analyses of patterns, as well as checking on individual cases. Stevenson never claimed that he’d “proven” reincarnation but only that he’d found sufficient evidence that it needed to be looked at seriously. In this way he was practicing essential science, where you never get so attached to any theory that you claim that it’s proven, only that you have certain kinds of evidence for and against it, and that your best guess, given the evidence so far, is…. An excellent introduction to Stevenson’s work is Thomas Shroder’s book, Old Souls (Fireside, 2001).

Psychiatrist Jim Tucker, one of the leading scientific investigators of reincarnation, starts his excellent book on this kind of research, Life Before Life (2005, 1–3), with the following case report, drawn from this collection of ostensible reincarnation cases at the University of Virginia Division of Perceptual Studies, which Stevenson founded:

John McConnell, a retired New York City policeman working as a security guard, stopped at an electronics store after work one night in 1992. He saw two men robbing the store and pulled out his pistol. Another thief behind a counter began shooting at him. John tried to shoot back, and even after he fell, he got up and shot again. He was hit six times. One of the bullets entered his back and sliced through his left lung, his heart, and the main pulmonary artery, the blood vessel that takes blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs to receive oxygen. He was rushed to the hospital but did not survive.

John had been close to his family and had frequently told one of his daughters, Doreen, “No matter what, I’m always going to take care of you.” Five years after John died, Doreen gave birth to a son named William. William began passing out soon after he was born. Doctors diagnosed him with a condition called pulmonary-valve atresia, in which the valve of the pulmonary artery has not adequately formed, so blood cannot travel through it to the lungs. In addition, one of the chambers of his heart, the right ventricle, had not formed properly as a result of the problem with the valve. He underwent several surgeries. Although he will need to take medication indefinitely, he has done quite well.

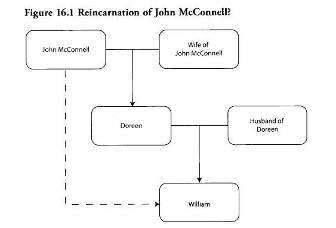

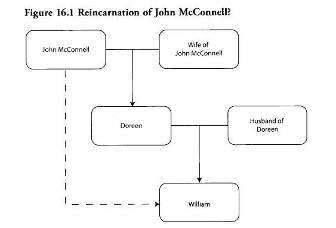

[I’ve sketched the relationship between various people in this case in figure 16.1 to make it easier to follow.]

William had birth defects that were very similar to the fatal wounds suffered by his grandfather. In addition, when he became old enough to talk, he began talking about his grandfather’s life. One day when he was three years old, his mother was at home trying to work in her study when William kept acting up. Finally, she told him, “Sit down, or I’m going to spank you.” William replied, “Mom, when you were a little girl and I was your daddy, you were bad a lot of times, and I never hit you!”

His mother was initially taken aback by this. As William talked more about the life of his grandfather, she began to feel comforted by the idea that her father had returned. William talked about being his grandfather a number of times and discussed his death. He told his mother that several people were shooting during the incident when he was killed, and he asked a lot of questions about it.

One time, he said to his mother, “When you were a little girl and I was your daddy, what was my cat’s name?” She responded, “You mean Maniac?”

“No, not that one,” William answered. “The white one.”

“Boston?” his mom asked.

“Yeah,” William responded. “I used to call him Boss, right?” That was correct. The family had two cats, named Maniac and Boston, and only John referred to the white one as Boss.

One day, Doreen asked William if he remembered anything about the time before he was born. He said that he died on a Thursday and went to heaven. He said that he saw animals there and also talked to God. He said, “I told God I was ready to come back, and I got born on Tuesday.” Doreen was amazed that William mentioned days since he did not even know his days of the week without prompting. She tested him by saying, “So, you were born on a Thursday and died on Tuesday?” He quickly responded, “No, I died Thursday at night and was born Tuesday in the morning.” He was correct on both counts: John died on a Thursday, and William was born on a Tuesday five years later.

He talked about the period between lives at other times. He told his mother, “When you die, you don’t go right to heaven. You go to different levels: here, then here, then here,” as he moved his hand up each time. He said that animals are reborn as well as humans and that the animals he saw in heaven did not bite or scratch.

John had been a practicing Roman Catholic, but he believed in reincarnation and said that he would take care of animals in his next life. His grandson, William, says that he will be an animal doctor and will take care of large animals at a zoo.

William reminds Doreen of her father in several ways. He loves books, as his grandfather did. When they visit William’s grandmother, he will spend hours looking at books in John’s study, duplicating his grandfather’s behavior from years before. William, like his grandfather, is good at putting things together and can be a “nonstop talker.”

William especially reminds Doreen of her father when he tells her, “Don’t worry, Mom. I’ll take care of you.” (53)

Coming back to general patterns, initial analyses of the University of Virginia collection indicate that a typical case starts with a preschool-age child spontaneously claiming to be someone who has died recently. While this is more likely to be noticed in cultures that accept the idea of reincarnation, such as India, it’s often not a welcome development for the parents, especially if the claimed incarnation is of a lower social status or caste than the current family! While such claims are liable to be ignored at first—the child must be imagining things or just playing—they eventually become persistent or dramatic enough, in the cases we hear about, that parents will begin investigating whether it was possible. Was there truly a person named so and so who lived in such and such place and died recently?

There are often behavioral indications that the child might be a reincarnation of someone else, such as markedly different diet preferences than those of his actual biological family and sometimes scattered words, even occasionally the use of a language the child has not learned in this life but which fits the claimed reincarnation.

The child frequently wants to “go home,” to be reunited with his real family, especially his spouse from the previous incarnation. When a reunion is finally arranged, there are sometimes dramatic instances of the child’s accurately picking out particular people from a crowd of onlookers, although this is sometimes hard to tell in the confusion surrounding the reunion.

Some of the most dramatic cases Stevenson and his colleagues collected are about biological markers, where the child has unusual birthmarks that correspond to the wounds that killed the previous personality. A child may show a small, roundish darkened area on his chest, for instance, and a much larger, irregular darker area on his back behind it, while claiming to be someone who was killed by a shotgun blast to the chest. Shooting wounds have small entrance holes and much larger exit holes. It’s as if the trauma of a violent death carries through strongly enough to affect biological development in the next life, and indeed, there are a few cultures that accept reincarnation, especially within families, that deliberately mark the corpse of a deceased person to see if a baby born later will bear those marks. (54)

Indeed there are enough cases in which children claiming previous incarnation showed unusual birthmarks and the previous personality had been violently killed that Stevenson used to joke that if you wanted to remember this incarnation in your next one, the best advice he could give you was to die a violent death. Stevenson documented many such cases in a massive two-volume work (1997a, 1997b).

Usually by the early school years, the memories of the previous life slip away and the child becomes “normal.”