Hot type to no type; when the story was all

I started as a copy boy at the Montreal Gazette in September 1967.

I’d been thrown out of university and needed a job, so I applied at the Gaz because the Star, the big paper in town, had no openings for an 18-year-old with high school leaving. I was offered two entry-level positions – selling advertising for $70 a week or working as a copy boy at $60.

“What gets me into the newsroom?”

“Copy boy.”

“I’ll take it.”

We reported to everyone – reporters, photographers, editors, composing room foremen, photo engravers, even Jake, the head copy boy. We were expected to replace anyone on a meal or cigarette break where a sentient body was required – switchboard operator, police reporter and occasionally, Wagner, the elevator operator. There was a dress code – white shirt, tie and grey flannels.

I loved it from the moment I set foot in the newsroom. The only problem was the pay – $42.15 a week clear.

I joked about it with the paymaster. He told me his story of going hungry because of Quebec politics. He’d grown up in Sorel at the height of the Depression, when it was run by the Simards at the time of Duplessis. His father, a Liberal, sold life insurance door-to-door until the Simards ordered their employees and anyone who did business with them to patronize only Union Nationale businesses. Anyone with a Liberal affiliation had to choose between poverty and exile.

The news cycle of that time was dictated and dominated by newspapers. Radio ripped, read and rode the police bands, chasing breaking news. Television worked with film, an inefficient news-gathering medium at best. The first electronic news gathering (ENG) units were yet to find work in Canada. There was no web, no Internet, no cellphones, no PCs, just fax machines and banks of teleprinters spewing copy from CP, AP, UPI and a dozen other wire services.

A copy boy’s Job No. 1 was to clear the wires, separate stories and make sure they went to the right department and desk. You’d know when the alert bells rang that something big was coming across the wire, and woe betide the hapless lad who forgot to check the Teletype room after stepping out for a smoke or an errand.

One learned who to serve first. If news editor Brodie Snyder yelled “Copy!” you’d scoot to his out basket and stuff what was in it into a plastic cylinder which you’d jam into a pneumatic tube, sending it to the composing room. We’d get Cokes for the deskmen and hard liquor for the old-timers who needed it to get a story out.

Recreational drugs were making their appearance in the workplace, but with Mother Martin’s next door and the Montreal Men’s Press Club uptown in the Sheraton Mount Royal basement, the profession ran on alcohol and male privilege. When I started as a copy boy in 1967, the Gazette newsroom was a man’s world, and the women worked at day jobs in Business and Family/Home/Lifestyle. Change was already underway. By the time I joined the Star in ’76, Donna Logan was running the newsroom.

For copy boys, there was no down time. Those of us who were literate were sent to the composing room to read right off the forms – steel frames into which compositors laid columns of lead type from the Linotype and Ludlow headline machines. Once locked with a key, the forms were taken to the press that created the mattes, impressions of the pages on fireproof material used to cast the lead plates that would be bolted onto the presses three storeys below.

Because our alphabet reads left to right, the type laid into the forms read backwards. On deadline, when there wasn’t time to take a galley proof, we’d read off the forms backwards and upside down (a skill I still use) to ensure that the body type matched the headline and lines weren’t missing or transposed.

In a union shop, we learned never to point. Offenders risked losing their fingernails to the steel pica ruler wielded by Eddie Hill, the composing room foreman. We leaned over to read with our hands clasped behind our backs, and pointed by voice. “Third column, second story, bottom lines transposed.”

Copy boys learned the newspaper industry from the ground up.

In the roaring pressroom, the black gang wore caps made out of folded newsprint. They would scoop a bundle of papers off the folder and hand them to us hot off the presses.

In the photo department we’d watch the photogs develop film and make prints, then hand us 8x10s for the photo editors. The photo desks would measure and crop according to their proportion wheels and send us up to photo engraving, where the photos would be transformed into zinc engravings to be inserted into the forms. It would be 20 years before Nikon would produce its first digital SLR, the F-1.

My break came when Paul Thurston, the overnight police reporter, quit to get a job flacking for one of the railways. For the next 10 years, the Gazette would be my family.

Front de libération du Québec

I’d been following the Front de libération du Québec since the first wave of bombings back in ’63, but my first experiences covering the socio-political tsunami sweeping Quebec were the February 1969 bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange and the McGill français riot a month later. The bomb injured 27 and inflicted structural damage, but the ultimate cost was to Montreal’s role as Canada’s financial hub.

McGill français was to prove no less disruptive.

Fired for challenging McGill’s anglophone elitism, poly-sci professor Stanley Gray fronted a vast mobilization with the help of Québec français firebrand Raymond Lemieux and McGill Daily editor Marc Raboy.

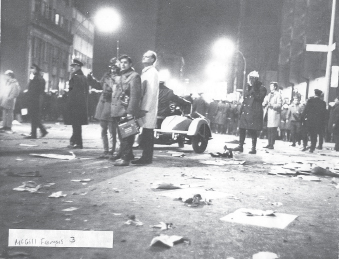

A crowd of between 6,000 and 15,000 converged at the corner of University and Sherbrooke to march on the school’s administration building. The riot squad, clubs in hand, formed a wall in front of the Roddick Gates, McGill University’s main entrance. Motorcycle cops pulled their sidecar-equipped Harleys into alleyways off the side streets below Sherbrooke and waited for orders to charge from behind. Reporters had a choice of where they wanted to be – relatively safe but immobilized behind police lines or in the crowd. We stuck with the crowd.

A police commander announced the gathering was illegal and ordered it to disperse. Loudspeaker harangues and posters gave way to rocks and flying picket stakes. Police Harleys roared out of their hiding places, cops in the sidecars swinging away as they careened through the packed crowd. We saw demonstrators struck by motorcycles and bystanders beaten bloody as they cowered in doorways and on staircases. Someone was dropping tire traps onto Sherbrooke St. – two four-inch nails with their heads cut off, each bent 45 degrees in the middle, then welded together to form a tire-piercing pyramid. They were courtesy of United Aircraft Local 510, the Pratt and Whitney union that financed its strikes with the sale of high-tech hashish pipes and rustic jewellery made from horseshoe nails.

For the next year, the FLQ fundraised with holdups while the RCMP, Sûreté du Québec (SQ) and Montreal police fought turf wars and collective-agreement battles. In October 1969, the Montreal cops walked off the job to enforce demands for danger pay and parity with their Toronto counterparts. It took 16 hours for the provincial government to order them back to work. During that time an SQ corporal was shot dead at a confrontation between taxi drivers and enforcers for Murray Hill, the private bus/limo service that held the Dorval Airport monopoly.

I wasn’t working that night but we were downtown on Ste. Catherine St. The mob ruled, smashing its way into shops and looting anything and everything. An elderly Italian implored my buddy and me to stand outside his shoe store, where we spent the evening cursing would-be looters. Around 9 p.m. the first SQ cruisers appeared in the downtown core. The shopping spree tapered off as cops began arresting people who had their arms full.

Monday, Oct. 5, 1970

By day, I was a sociology sophomore at Loyola College. At night, I was a Montreal Gazette police reporter, spending most of my shift working the phones and asking cops if they had anything going on. Usually the answer was nothing. Occasionally I’d write a filler on a holdup. Once in a while I’d get a tip on a big story, usually ending up assigned to a general reporter. We had a term for it: Bigfooted.

The Gazette police desk competed fiercely with our opponents at the Montreal Star. We were the newsroom’s go-to Rolodex. We knew how to get the names of owners, occupants, neighbours, addresses and phone numbers. We called next of kin. We chased sirens with our Bearcat police scanners cranked up.

We were three of us on the Gazette police desk – Eddie Collister, Albert Noël and me, the rookie. Eddie was terrific at talking to people. He could reach police brass and mob lawyers. His contacts were everywhere. He would meet a Station 10 detective in the privacy of an X-rated film house near Atwater and a Mafia mouthpiece above a drug den. Albert and I had worked together at the Quebec Chronicle-Telegraph, where I was learning Quebec’s official language. When he joined the Gazette, Albert didn’t drive and I was still picking up Québécois French, so we’d double team – Albert because the cops took to him like a brother and me because I had a Volvo and a camera.

I was between classes that Monday when my Gazette Pagette beeped. I ran for the closest pay phone and called the desk. Eddie answered. “A British diplomat (James Cross) has been kidnapped from his house on Redpath Crescent. How fast can you get over there?”

“Twenty minutes, tops.”

The poor man’s Maserati, my burgundy Volvo 123GT with the whip antenna poking out of the centre of the roof, was illegally parked nearby. I shot around the foot of the mountain, then past the hospital as I headed for the enclave of brick half-timbered homes a brisk walk from downtown. The street outside 1297 was packed with reporters, photographers and cameramen. The high point of the stakeout was watching the cops apprehend two men engaged in a personal activity on the mountain. By then it had gotten too cold to sleep in the car so I headed back to the newsroom.

Gazette photographer Garth Pritchard was asleep on my desk, using a Montreal phone book as his pillow. He’d turned down the police radio; I turned it back up. He woke up spouting threats, but grabbed his photo gear. We jumped into the Volvo. I cranked up the Bearcat and headed across the Jacques Cartier bridge.

We had no clue of what to look for. We crossed to the South Shore and drove streets we didn’t know, looking for police activity, something, anything.

It was past midnight when Garth put his hand on the gearshift. “Duffer, this is stupid. We don’t know what we’re looking for. Let’s go get Dilallo burgers.”

As it turned out, we didn’t have to go looking for news. For that first week we ran – to the SQ’s massive bunker on Parthenais, to RCMP headquarters in Westmount, to CBC studios in the old Ford Hotel (where announcers would read the FLQ manifesto), to Canadian Army command at Longue Pointe, to pro-secession rallies at the Centre Paul-Sauvé and the Université de Montréal. That week the three of us came to realize the cops had no more idea of what they were looking for than we did.

On the 10th, Chénier Cell members snatched Quebec’s Deputy Premier and Labour Minister Pierre Laporte while he was tossing a football with his nephew.

A week into the crisis, the Gazette police desk was a 24/7 operation; we napped and ate on the fly as Ottawa and Quebec fought over how far society should go in appeasing terrorists to free Cross and Laporte.

The next Saturday I was watching a movie when my Pagette went off. I called the desk. No answer. I called the newsroom. They’d found Laporte’s body in the trunk of a car near the St. Hubert airport on the South Shore. Garth was there. He had photos of Laporte’s body.

The next night we received a tip from a usually reliable source – the gun-toting wife of SQ tactical squad’s Albert Lisacek – to head for St. Hubert’s Armstrong Blvd. Investigators had found the house where Laporte had been executed. We jumped in the Volvo. Garth was riding shotgun. TorStar photog Graham Bezant was in the back seat. I saw an SQ cruiser and pulled in behind it as men in plainclothes swarmed us. I rolled down the window and was digging for my driver’s licence when the cop on Garth’s side told us to freeze. Bezant, who didn’t speak French, reached into his jacket. The passenger-side cop cocked his revolver and put it to Garth’s head.

Suddenly, we heard Lisacek’s familiar voice: “What the fuck are you boys doing here? Good thing my guys were feeling relaxed. You could be dead.”

He told us a Volvo like mine had been posted to the SQ watch list after a patroller saw one cruising through Longueuil the night Cross was kidnapped.

I asked Garth if he was okay.

“I will be once I get my hands around your throat. You were laughing, you dumb fuck. You thought it was funny.”

Living Rough

Gaz reporters learned to live rough.

My first Montreal crash was the Rathole Arms, a condemned rooming house on Richmond Square. The province had expropriated it for the Ville-Marie Expressway, but construction was delayed, so we pried the plywood off the front door and made ourselves a home. The Satan’s Choice biker gang took the downstairs. They’d wheel their choppers in off de la Gauchetière for the night and chain them to the cast-iron radiators in the long hallway. I lived upstairs with a bunch of musicians, artists and a couple of underage runaways.

The bikers made sure we weren’t undercover cops by inviting us to smoke hot-knife hashish with them. The power had been cut off but we tapped a line into a neighbour’s place to run a stove we found. We had to carry water. I slept in a hammock because I couldn’t take the rats running across my sleeping bag. Weekends I went home so I could shower and do laundry.

Winter came. Without heat the building became uninhabitable. The Choice moved into a ground-floor flat farther east on de la Gauchetière. We stayed in touch. I found a cheap room on Hutchison, a block above Sherbrooke, next door to one of the city’s most respected purveyors of recreational pharmaceuticals. The New Penelope and the Swiss Hut were at the end of our block. Café André was just around the corner. The Spanish Club stayed open late and offered cheap beer and wine; Mazurka’s served a reasonably priced bowl of soup with plenty of fresh Polish rye bread. On paydays, when I was feeling flush, I’d head over to Ben’s after my 2 a.m. shift, order a medium smoked meat, fries, dill pickle, cherry Coke and watch the nighthawks. It was the life I dreamed of.

Eventually I got a raise and moved up the lodging chain to a highrise at the corner of University and Milton, where I hung out with some of the people who trashed the Sir George Williams computer lab. There was a little pizzeria on the ground floor. I was having a late lunch there one day, talking to the owner, when a guy walked in with a huge brick of mozzarella. The owner opened the cash and counted out a bunch of bills.

“What’s that about?”

“You don’t want to know.”

“No, seriously …”

“I have to buy my cheese from him.” He said it was a form of protection. Buy from X and nothing bad would happen to his pizzeria.

It wasn’t long after that that Louis Greco was killed and his brother Tony seriously burned when Tony’s pizzeria blew up. Police said they were cleaning the floor with kerosene.

(There are brands of cheese I will not buy.)

From the McGill Ghetto, Hubert Bauch and I moved to a house on Grosvenor in Westmount. Hubie was the ideal roomie – neat, quiet, and always supplied for a party. He and I moved to a journalists’ group home on Prospect Ave. It was a fin-de-siècle mansion turned into a warren of tiny rooms, all of them occupied by Gazette reporters and Canadian Press deskers and their respective friends. Our Prospect Garbage Can Punch Bash was a 36-hour bacchanalia, complete with Satan’s Choice hogs parked in the back alley. The Choice kept a low profile while visiting above the tracks.

The Judge’s Horse

In the early ’70s, the Trudeau government began expropriating land northwest of Montreal for what would briefly become the world’s largest airport. Mirabel would turn Montreal into Canada’s eastern gateway. It would be an airport far enough from civilization to allow the noisy Concorde and its supersonic transport (SST) competitors to land 24/7. Hobbled from the outset by unfinished Highway 13 and a broken promise of a high-speed shuttle, Mirabel was, however, doomed before construction began when the Americans and Soviets scrapped their SST programs.

Ottawa persisted in the face of vociferous opposition. Farmers, some of them descendants of Quebec’s 17th-century habitants, dug in for a long fight with the backing of the Union des producteurs agricoles, Quebec’s farm lobby. Others were quick to flip their land to speculators “assembling” the site on behalf of the federal lands acquisition agency. To cover their costs in the interim, these vultures rented out the farms.

That was how Anthony Gilliland came to shoot the judge’s horse.

June 26, 1972. Albert got a tip from the SQ. Someone was holed up in a farmhouse on a range road in the middle of nowhere, holding his family hostage and threatening to blow everyone up if the cops tried to arrest him. The SQ was trying to keep a lid on the story because those involved didn’t want media attention.

We had the address but it took us half a day to find the place and only after we spotted the SQ cruiser parked at the entrance to the driveway. As we walked up to the house, a man’s voice from an upstairs window ordered us not to move. In English. We told him we were Gazette reporters. The voice’s owner came downstairs and asked us in. He was haggard from lack of sleep and he was carrying a single-shot 22-calibre rifle. Behind him was a woman with an infant in her arms. Four children were perched on the staircase, watching us through the balustrades.

We sat around their kitchen table as Gilliland told his story. The couple had rented the 60-acre farm from one of those Mirabel land-flip speculators. Next door was a stable that boarded horses for a riding club which included several Montreal lawyers and a well-known judge. It was used mainly evenings and weekends for activities that included young women.

The Gillilands lived on welfare. They had moved to Ste. Scholastique from Two Mountains in search of a healthier lifestyle. Their garden was their only source of food, and they were hoping to put up enough to survive the winter. Horses from the stable next door had trespassed repeatedly onto their farm and trampled or eaten some of their vegetables. The Gillilands complained to the stable owner, without results. When the horses returned the day before, Gilliland shot at them with his rifle.

This time the cops were quick to show up to arrest Gilliland for injuring four horses, causing one to be put down. Gilliland told them he was holding his wife and kids hostage and would blow the place up if they tried to arrest him. The SQ backed off.

Albert and I made a quick decision. There was no phone in the house. To call the story in I had to drive to the nearest pay phone, then head back to Montreal with my film. But what if I couldn’t get back in past the cops?

“I’ll get you back in,” Albert said. “Remember, a carton of Viceroys.”

When I returned to the house the SQ cruiser was parked in Gilliland’s front yard and the cop waved me in. Albert and Gilliland were smoking on the front porch.

“I told them you were the English hostage negotiator,” Albert said. While I was gone he’d gotten the rest of the story from the SQ. The judge wanted Gilliland’s head for killing his horse, but was media-shy for reasons that had to do with what went on at the riding club. The SQ warned the judge they wouldn’t be able to control the story if it went to court.

As we talked, our arch-enemies drove into the yard. Veteran Montreal Star police reporter Paul Dubois and a photographer started toward the house.

“He’s an asshole,” Albert told Gilliland. “Tell him to get off your property.”

Gilliland did better than that. He went upstairs and stuck his rifle out the window, as he did with us.

“Get the fuck off my land!” he shouted.

Dubois and the photog scampered to the SQ cruiser and exhorted the cop to take action. The cop shook his head. Dubois and the Star photog got back into their car and took off in a cloud of dust.

Dubois got the last word. His Montreal Star story painted Gilliland as a shiftless loser with a grudge against his neighbours, a layabout who refused offers of employment from the caring stable owners. The Star also quoted the land-flip vulture, saying he was cancelling the Gillilands’ lease and giving them 30 days to vacate.

Eventually, Gilliland was arrested and the case went to court. The judge with the dead horse declined to press charges. Anthony Gilliland and his family disappeared without a trace.

Pre-digital

There’s something to be said for pack journalism, newsers, scrums and digital recording devices – it’s hard to get it wrong. Not so in the days before digital.

Ste. Thérèse, Friday, July 28, 1972. A city cop shot 16-year-old André Vassart in the back, killing him because Vassart, a suspected drug dealer, was outrunning him. Protests turned into a riot. The mayor banned public gatherings and called in SQ reinforcements. Over the next three days, 30 people were arrested amid accusations of police brutality. The Gaz missed the story because the Saturday paper went to press early. There was no Sunday Gazette.

The assignment desk dispatched me to Ste. Thérèse to write a follow for the Monday paper. I headed over to the local tavern, my usual point of contact in a strange burg. A pitcher of beer later, I had the bones of a story. I headed out onto the porch, where half a dozen locals were taking in the afternoon sun in violation of the Riot Act.

A passing Ste. Thérèse police cruiser slowed when the driver saw us. “Chiens sales!” someone barked. The driver slammed on the brakes. A cop jumped out and ran up onto the porch waving his matraque, a two-handed riot club. We ducked and scattered. One, a slight fellow I had talked to earlier, wasn’t fast enough. The cop grabbed him like a rag doll and dragged him to the cruiser but couldn’t get the back door open. Somehow, he’d locked himself out. His partner behind the wheel drove off to jeers from the crowd. The cop he left behind yanked open the back door of a passing SQ cruiser, pushed his prisoner into the back seat and followed him in.

The SQ cops shouted at him to leave them out of it. Like something from the Keystone Kops, the Ste. Thérèse flic pushed his prisoner out the far door and frogmarched him down the main drag to local police headquarters. I tailed them inside.

Inside, a man was at the counter talking to the desk sergeant about keeping an eye on his house while he was out of town. The cop pushed his prisoner into a bathroom behind the counter, jammed the man’s head into the toilet and flushed it. Twice, three times. Then the beating began. The vacationer and I looked at each other in shock as the beefy cop rained punches on the unresisting prisoner. Until that moment I’d only heard stories about police brutality. Realizing there were spectators, the desk sergeant ordered the assailant to stop. Together they half-dragged the unresisting victim through another door. I saw a cellblock before the door closed. On my drive back to the Gaz, I wrote my story in my head while loathing myself for not intervening.

Back in the newsroom, I told city editor Mike Daigneault what I’d witnessed. He questioned me closely. What exactly did you see with your eyes? Hear with your ears? Who else was there? What can you confirm? Do you have names?

While I’d been talking with locals at the tavern, I had jotted “René Jean” in my notebook. I was convinced he was the same person having his head jammed into the police station toilet. I took the numbers off the SQ cruiser and Ste. Thérèse police car. I had the name off the desk sergeant’s chest pin, but I didn’t recall seeing an ID pin on the cop doing the beating. I should have asked the vacationer his name.

“Write it,” Daigneault said.

The desk splashed the story across front page, above the mast.

Mike called me first thing the next morning. “Better get in here,” he said. “The cops and the city are denying everything. They’re saying you made the whole thing up. They want a retraction and an apology on front page.”

It was my initiation to the serious-self-doubt club. If I couldn’t prove it, I was done. Discredited reporters quickly become ex-journalists. It’s a career-ender, and it should be.

Mike went over the options. If I had doubts about anything in my story, a retraction would be the only way out. I had no doubts. Next was to try to find witnesses or, better, the victim himself. I spent the morning on the phone getting nowhere. Around noon I ducked out for a bite. Wagner, our elevator operator, stopped me as I was boarding his cage. “Couple of guys in suits in the lobby. Maybe you want to take the back stairs to the loading dock.”

I figured he was pulling my leg. “No, I’ll go down and see what they want. If there’s trouble, you can handle it.”

I exited the elevator and walked toward them. There were two spiffy dressers, with short hair and $200 shoes. “Can I help you?”

“Monsieur Duff?”

“Yes. And you are …?”

Their badges said Sûreté du Québec. Their cards identified them as SQ internal affairs sergeant-detectives.

“We would like to talk to you.”

“Right here is fine.”

“No. Outside, in our car.”

“What if I don’t want to get into your car?”

All they wanted was a signed statement from me attesting to what had transpired in Ste. Thérèse and the SQ’s involvement.

Wagner was still waiting, something I found comforting. “Tell the newsroom the SQ is taking me for a ride.”

An unmarked Chevy was illegally parked on Ste. Antoine, with two more plainclothes cops waiting in the front seats. My shepherds folded me into the back seat before sandwiching me between them. One pulled out a clipboard. “Just tell us what you saw. No opinions.”

I retold the story. The guy acting as the recording secretary then read it back to me and I signed it. One of them got out to let me out.

“What if I had refused to get in the car?”

“We would have gotten a warrant and taken you to Parthenais to spend a night thinking about it.”

Back at the paper I worked the phones until everyone had gone home. On the plus side, we had not heard from the town lawyers, but I had nothing to hand in. I slunk out of the newsroom, through a gauntlet of stinkeye from the city desk.

I spent a sleepless night and dragged myself into the office.

Daigneault was waiting in his office doorway. He handed me that morning’s Le Devoir. “Saved by the competition.”

There it was, “Bel et bien battu” splashed across their front page with a photo of René Jean stripped to the waist and a doctor pointing to huge welts and bruises covering his body. Except that he was identified as Clément Poudrier.

Le Devoir’s story quoted a doctor at the Ste. Thérèse medical clinic who examined the patient, as well as the police director who said the prisoner had incurred the injuries while the arresting officer was applying a standard armlock to subdue him. There was no mention of the toilet.

Daigneault wasn’t one to let me off the hook. “This time you’re lucky. But you’ll be clearing out your desk the next time you get beaten on your own story.”

James Bay

Thursday, Nov. 15, 1973. After 71 days of hearings and months spent writing his decision, Quebec Superior Court Justice Albert Malouf granted the James Bay Cree and their allies an injunction halting the $6-billion James Bay Energy project. Legally, nothing could move on the site until Quebec’s Court of Appeal heard the case. Earliest opportunity: Monday.

I’d been covering the Malouf inquiry for the Gazette. The Cree, the Innu, the Inuit – every First Nations community that would end up being affected by the James Bay and subsequent developments – had their day in court. It was David vs. Goliath, the brilliant James O’Reilly and his clients Robert Kanatewat, Billy Diamond, Philip Awashish, Zebedee Nungak and the Inuit Tapirisat against the crowd of legalists representing Hydro-Québec and its creatures, the James Bay Energy and Development corporations.

An injunction hearing is the closest thing there is to high drama in Canadian courts because it’s the only venue where a judge is asked to decide the outcome based on whichever side is more successful at proving it will be worse off if it loses. Malouf had to decide whether the traditional rights of 5,000 hunter-gatherers outweighed the socioeconomic interests of five million Quebecers.

The court heard about country food, the aboriginal seasonal diet of Arctic char, seal, bear, moose, caribou, beaver and goose. It heard how Ottawa ceded control of the District of Ungava to Quebec, but not its ownership. It heard how the La Grande River would become the continent’s largest hydroelectric generating complex by flooding thousands of square kilometres, and forcing the Cree off their traditional hunting and trapping territories. Burial places where they visited their ancestors would be underwater.

Hydro’s lawyers portrayed the Cree as nomads without ancestral attachment to the lands being flooded or built on. They also tried to prove the James Bay Cree had already adapted to the mainstream Canadian diet and consumer technology – snowmobiles, ATVs, outboards, television, movies and so on. But the bulk of their case was that Quebec’s growing need for hydroelectricity should tip the balance of convenience in Hydro’s favour.

Within minutes of Malouf’s bombshell, reporters scrambled to book the first flight to James Bay to see whether the project had been shut down. Nordair had scheduled 737 service flying workers in and out of the project via Matagami, but to be allowed on the plane one had to have authorization.

So our Gazette/Southam posse – Southam’s Bill Fox, Gaz photog Garth Pritchard and I – booked a flight to Fort George, now Chisasibi, the Cree community at the mouth of the La Grande where it flows into James Bay. We’d fly to Matagami, then hop off at La Grande to catch another Nordair flight the half hour to Fort George.

Matagami airport was jammed with workers in transit and journalists who weren’t being allowed to travel on. We hooked up with Raymond Saint-Pierre, then a CKAC radio reporter, and explained how we hoped to sneak onto the project via the road from Fort George. Together, we bullied Nordair staff until they threw up their hands and allowed us back onto the 737.

At the La Grande airport, we were hustled off the plane and into the ramshackle terminal. We could see the ancient C-47 that was supposed to carry us to Fort George but we weren’t being allowed to board. It took a loud argument between Nordair and James Bay Development Corporation staff to learn why. The C-47 was inoperative and there were no seats available on the departing 737. There was nowhere for us to go, nowhere for us to stay. So we were placed under arrest and transported to the airport manager’s trailer.

“I’m not locking the door,” warned the beefy James Bay Constabulary cop. “But don’t think of wandering off. There’s nowhere to go, and we’ve seen wolves around here.”

The airport manager, Pierre MacDonald (later to find fame with his grosses maudites anglaises), was out of town so we made ourselves at home. There was plenty of booze in the fridge. The freezer was filled with moose steaks and Dunn’s smoked meat.

We heard an explosion. Pritchard grabbed his gear, and he and Fox headed out the door. Half an hour later they were back with pictures of construction in full swing.

That was enough to send Saint-Pierre searching for a phone. We found one disconnected, stashed in a desk. He tried a phone jack; it worked. He reached an operator somewhere on the site and called the CKAC newsroom. Right away they put him on air with the story of how construction on the James Bay project was proceeding despite the injunction. We cracked open several of MacDonald’s beers and poured ourselves vodka chasers.

We were in the midst of celebrating when we heard the J-Bay constabulary truck roar up to the Atco. “Quick, hide it!” Saint-Pierre said, handing me the phone. I yanked open a closet door; inside was one of those miniature washer-drier combos. I thrust the phone into the washing machine just as the cops burst in.

“All right, who’s got the phone? Give us the phone!”

“What phone?”

They looked around the place, couldn’t find the phone and left. This time they locked the door.

They weren’t gone 10 minutes before Saint-Pierre was back on the line to Montreal. A former law student, he questioned whether the James Bay Energy Corp. was in contempt. He told the story of the injunction hearing to a huge audience heavily indoctrinated by Hydro’s advertising blitz.

All that in two minutes, leaving us plenty of time to hide the phone.

The second visit by our constabulary warders was unpleasant. “If you don’t produce that phone, we have orders to throw you out.”

We’d had a few drinks at this point. We jeered them. I stripped naked, ran outside and dived into the snow. Pritchard said later that I was ranting about how they couldn’t scare me, how I could survive the cold. “Duffer, they thought you were nuts. That’s why they left.”

The last visit was almost casual. Saint-Pierre was still on the phone when the cops burst in. They grabbed it out of his hands, ripped it out of the wall and took it with them.

Suddenly, the JBEC couldn’t get us off their territory fast enough. By Saturday we were back in Montreal. I wrote this story and handed it in.

“You’re not the story, Duffy,” said Kevin Boland, a copy editor on the city desk. “Put this through the typewriter again. Write it straight. Lose the vertical pronouns.”

So I wrote it straight.

Hotel Matagami

March 1974. Southam’s man in Montreal, Bill Fox, slipped the bouncer a twenty to grab a wall table where we could watch the freak show in the hotel bar. It was near midnight in this haphazard huddle of construction trailers and prefabs 800 kilometres north of Montreal. This outpost of civilization was jammed with labourers evacuated from the James Bay hydroelectric project after union goons trashed the LG2 construction camp 600 kilometres farther north.

We were prescient enough to have pre-booked a couple of rooms for our Gazette/Southam posse but sleep was impossible. The prefab barracks rattled from drunks bouncing off walls and vigorous fornication as sex workers entertained the cash-flush horny hordes. Fox and I filed our stories and we all headed downstairs for food and drink.

It was the kind of bar where the girls waiting table alternate with the girls stripping onstage. “No, no, baby, we don’t kiss,” the barmaid warned the roustabout at the next table. The crowd couldn’t keep its hands off the waitresses hefting booze. The bouncers were equally quick to muscle gropers and brawlers. We were glad to be sitting next to a wall as we downed $8 beers and tucked into leathery $20 steaks.

Blokes tend to stick out, so we stuck together. Fox, a Timmins native, knew how to keep his head down when the bottles and chairs started flying. Gazette photog Garth Pritchard, who shared a ski chalet with members of the West End gang, came equipped with a trouble radar.

We all felt the trouble in the air. “La saccage d’LG2” was one of a series of political eruptions shaking Quebec between the 1970 FLQ crisis and the 1976 Parti québécois sweep. There was a war on between Quebec’s two major labour unions over who should control the major construction sites, including the James Bay hydroelectric project and 1976 Montreal Olympics. It’s a Québécois axiom that he who gains control of a worksite is guaranteed well-paid work for family, cronies and colluders, a pattern we’ve seen repeated despite commissions of inquiry led by Robert Cliche and France Charbonneau almost 40 years apart.

We were living in print journalism’s heyday, the golden era before instantaneous data transmission and memory chips. Reporters were a newspaper’s eyes and ears. We filed by wire or dictated to rewrite editors. Photogs shot in black and white and had to find somewhere to develop their film. Photo transmission was laborious; colour photos took four separations. Newspapers reserved colour for their Saturday fronts.

We lived in two worlds – in the newsroom and on the road. Some people loved the bogus collegiality of the newsroom, in truth a vicious, backbiting forum for petty intrigue. Others died a slow death in the newsroom, consuming in excess to anaesthetize the tedium. We looked for any excuse to hit the road and our editors were happy to oblige. When we were on the road they didn’t have to find something for us to do.

Cooking Up a Story

June 1975. City editor Jim Peters called me into his office.

Peters was one of the Toronto Telegram refugees who transformed the Gazette from the Grey Lady of rue Saint-Antoine into a serious journalistic contender.

“Duffer, go find a job. In James Bay.”

Long before it made its way onto the list of ethics transgressions, the Gaz was embedding reporters without the host’s knowledge. Gillian Cosgrove had put together an award-winning series based on her experiences in the Batshaw Centre, a system for English-speaking youth experiencing some kind of crisis in their lives. Some claimed it wasn’t ethical.

Not me, not after the Malouf injunction hearings and the four days it took Quebec’s Appellate Court to overturn months of testimony by honest people who had placed their faith in white man’s justice. I visited a JBEC-approved employment centre to find out who was hiring. Hardrock miners were in big demand, followed by heavy equipment operators, truck drivers, mechanics and a long list of jobs I wasn’t qualified for. Eventually I found one: cook. Crawley & McCracken, the same firm that ran Murray’s restaurants, had the contract for all the kitchens, cafeterias and dining halls in the territory. They were desperate for staff. It paid badly compared to every other job on site and employees were forced to work split shifts. Turnover was high; most cooks quit after a month.

I dropped by the Crawley & McCracken offices in Old Montreal to pick up a application form and chat up the secretary. There was an immediate opening for a cook second class at the survey and core-sampling camp in LG-3, a half-hour helicopter jaunt upriver from LG2. All I had to do was fill in the form, get a medical and report for duty.

My pal Mike Dobbie ran the Château du Lac, Hudson’s local bar and grill. On Château letterhead, Dobbie wrote a flattering letter about my imaginary skills as a breakfast chef, steak chef, salad chef and baker. I spun a CV listing my years of experience and handed it in with my application. Two days later, a doctor was giving me a physical. The next day I was lining up for the Nordair shuttle to Matagami and La Grande.

First stop was a JBEC checkpoint to ensure we were authorized to travel to La Grande. I was on the list; they waved me through. Three hours later, I was in a minibus driving past the LG2 airport manager’s trailer where we’d been locked up a year earlier. My travel companions were a biology student from Université Laval and a Montreal teen whose parents were desperate to get him out of the house for the summer. We overnighted at Crawley’s transit bunkhouse before being loaded onto the early helicopter shuttle for LG3.

Nothing prepared me for the immensity and beauty of the James Bay region, especially as seen from a helicopter. One could see for a hundred miles in every direction without seeing a trace of civilization. We followed the La Grande, as yet untamed by the complex of dams, reservoirs and forebays that now stretch to the Labrador border. Suddenly, LG3 was beneath us, a collection of tents on platforms huddled on the shoreline where the La Grande narrowed into a canyon.

I was directed to the Crawley bunkhouse. The chef was asleep in his bunk when I walked in with my kit. It was around 9 a.m. so I walked around the camp. Late in June, drifts of snow remained. The prefabs and tent platforms were afloat in a sea of mud. When I returned to the tent the chef – a short, balding guy built like a bag of cement with simian arms – was struggling to wake up. I introduced myself. He gave me a long, hard look that told me he didn’t like anglos.

“Ever cook in a camp?”

No, I confessed.

“Never mind. You’ll learn. Time to get working.”

Serge was from the Abitibi, where men lived half their lives in lumber camps, construction camps or mining camps. Camp food was what they ate – starch, meat, protein, carbs and lots of it. The afternoon began with us making 600 doughnuts in the fryer, baking cakes and bread pudding in big square pans. Besides Serge, my bunkies included two assistant cooks.

LG3 was a survey camp, which meant packing 125 lunches because nobody returned to the camp to eat. We made mountains of sandwiches for next day’s lunch, then wrapped everything and put it in the walk-in cooler to be taken out at breakfast along with donuts, cake and boxed fruit drinks. Then we rolled 600 cigars au chou (cabbage rolls). I flipped pork chops on the grill, mashed cauldrons of potatoes and tended to the official Crawley vegetable medley of peas, carrots and celery.

Around 4:30, the helicopters began shuttling the survey and coring crews back from the surrounding hills. At 5 sharp, the dining hall doors opened and the ravenous mob poured in, grabbing trays and loading up. They’d spear three chops and half a dozen cabbage rolls as we’d dump a pound of mashed spuds and a ladle of veggies on the plate. Dessert was cake, pie and pudding. Everything we put out ran out.

Dinner rush over, we pulled next morning’s bacon out of the freezer, loaded the coffee urns and set up the counter for the breakfast rush. Then we washed up in the communal bathhouse, headed to the bunkhouse and crashed by 8 p.m.

Up at 4:30. Coffee on, beans and oatmeal on the range and bacon frying to half done as we broke eggs into dessert bowls ready to be dumped onto the grill or into the poaching pot. We put out the lunch fixings at the same time. At six sharp, the crowd poured in and we were frying nonstop. The mountains of sandwiches and baked goods disappeared into lunch boxes.

As we cleaned up, Serge turned to me. “Got it?”

“Got what?”

“Breakfast. You’re in charge tomorrow.”

I was up at 4 a.m. The tent stank. I headed outside to clear my head. The pre-dawn chill was already lifting; mist covered the La Grande, oily smooth and tea-coloured. I grabbed my towel, stripped off my pyjamas and waded into the river up to my neck. The bone-chilling water snapped me awake. A few fast laps and I’d had enough. It became my routine for the next month.

It passed quickly as I found time between shifts to talk to as many people as I could. Quebec’s population back then was around five million, but in many ways, the province was still a huge small town. One helicopter pilot kept looking at me; he looked familiar.

People loved to talk about the project, beginning with the cost ($14 billion in 1987 dollars), the environmental impact, the benefits for Quebec society – but not about the impact on the region’s aboriginal peoples. The Société d’énergie de la Baie James (SEBJ) decided to deforest and scour plant life from the future reservoirs after a study of Ontario’s Grassy Narrows inhabitants found high levels of mercury, and postulated that the poisonous heavy metal could have leached from flooded forests. (Decades later, it was revealed that the provincial government knew the source was a nearby paper mill.)

On one of our walks through the hills around LG3, the Laval biology student counted 150 annual growth rings in a black spruce the size of an average Christmas tree.

Corruption was a perennial topic. I heard stories of 300-kilometre helicopter flights for booze and cigarettes, of colossal overtime bills, of lucrative contracts for people doing nothing. Mostly, I heard stories about the old-timers who lived most of their lives in camps, like the guy who kept a woman in an apartment and lavished her with cash, a Corvette, jewellery and furs for six months so he could dream of the fantastic vacation awaiting him. Then he would throw her out and find someone else.

And politics. Outside Montreal, Quebec City, Hull and Sherbrooke, Quebec in 1975 was French-speaking, nationalistic and happy that way. I’d explain my accent by telling the suspicious that I was a Scottish nationalist. Then they’d rag on maudit traitre Trudeau et son stooge Bourassa. Most were chomping at the bit to elect René Lévesque and the Parti québécois, toss the hated English out of the top jobs and become maîtres chez nous, (masters of their our own house). As I write this, I remember returning to La Grande for the project’s inauguration in 1979, where the crowd booed Lévesque and cheered Robert Bourassa, who would make a return to politics in 1986 as the father of the James Bay project. Quebec is so fickle.

Three weeks into my assignment, I was outed. Chris, the helicopter pilot, finally placed me. “I know you. You’re a Gazette reporter. I flew you last year.”

I didn’t try to deny it and asked him not to blow my cover. He said he wouldn’t, but he must have told other pilots, because the word got out. Less than a week later I was called to the SEBJ camp supervisor’s office.

“I have learned that you are a journalist. Your contract is cancelled. You’ll be flown out of here as soon as we can get a plane in. I strongly advise you not to leave your quarters.”

Officially, I was another “jompeur.” The camps even had a verb for it, “jomper.” It applied to anyone who didn’t or couldn’t fulfill the terms of their contract for whatever reason, like the guy found outside with his luggage in the rain who said he was waiting for the bus.

Serge was pissed. He’d have to start getting up at 4:30 again. “I was thinking of a vacation and you go and fuck me. Fucking English.”

I told him to look on the bright side. Robert was ready to take over breakfast.

Late that afternoon, an old single-engine Otter on floats landed upstream on the La Grande and let the current pull it down to the tiny beach where I began my mornings. I was the only passenger. An hour later I was back at LG2.

Then began the strangest part of my sojourn. Officially, I was one of hundreds waiting to fly out on rotation, R&R medical leave or because their contracts were up. How soon we departed depended on our place in the waiting list for one of the precious seats on Nordair’s 737.

So I spent the next three days walking unescorted around LG2.

I ran into people I knew who told me more stories about corruption and environmental problems. I was invited to Radisson, the trailer city where subcontractors maintained bunkhouses and their occupants brewed beer, distilled shine and grew weed. I talked with teachers, nurses and secretaries about what it was like being a woman in a place where women were heavily outnumbered and underpaid. Some loved the place. They’d met someone, they were making real money and saving for their first house and a kid. Others dreaded the weather, cursed the isolation and waited for the next rotation out.

Finally, a seat on the 737 came available and I flew back to Montreal. I spent the next week writing my story from notes and photos, splitting it into five parts that would run for a week. It was published that fall and drew immediate fire from the SEBJ, Hydro-Québec and Crawley & McCracken, all of whom claimed I’d cooked up stories from a bunch of kitchen talk.

I still love to make breakfast.

JoJo and the Judge

Growing up, I loved to fly. Now I’m a white-knuckled, we’re-all-gonnadie reluctant passenger, cringing at every shudder and yaw. By my reckoning I’ve been living on borrowed time since James Bay.

The fear began with a hard landing. A very hard landing. The Gazette had chartered a speedy Sud Aviation Gazelle to fly us into La Grande in the wake of the sacking of LG2 by union goons in March 1974. If we weren’t allowed to land, my plan was to jump out with my backpack and hike in to the scene of the crime.

Maybe it’s a good thing, but the engine lost power and forced us down on a frozen lake somewhere between Matagami and La Grande. Even better, there was a survey camp on shore for the crews surveying the route of the future power transmission lines. Within the hour, we were aboard an Alouette, a plodding workhorse chopper which took us back to Montreal with nothing to show but a colossal bill.

Then there was the Cessna Skymaster icing incident. Gazette photographer Garth Pritchard and I were heading to LG2 when we ran into serious icing conditions. The Skymaster’s de-icing boots couldn’t handle the buildup. If it got too thick the Cessna would drop like a stone.

But I didn’t know that until the pilot dropped the nose and began turning us around.

“What’s happening?” I asked from the back seat. “Why are we turning around?”

“Ice!” the pilot said.

I started to argue. We had to get to LG2 for a big announcement.

Garth, sitting next to the pilot and witness to the developing emergency, lost it. “You stupid fucker, we’re going to die if we can’t get below this ice! Shut the fuck up or I’m going to hammer you stupider than you already are.”

I kept quiet. The pilot raised the cabin heat to max and lost altitude to where the de-icing boots would start working. We flew back to Montreal without a story.

Then there was Jojo and the Judge.

Before the James Bay hydroelectric project was launched, the District of Ungava was administered by a body called the Direction générale du Nouveau-Québec. With the creation of the Société d’énergie de la Baie James, it was agreed that indigenous offenders would no longer suffer the trauma of being flown south for trial. Instead, the judge would come to them, a flying Quebec circuit court.

I succeeded in convincing the provincial Justice Ministry it would be good PR to allow a reporter to accompany the judge and his entourage on their private government aircraft. In the spring of 1975 I met up with the court at a hangar in Dorval. Our private plane was an ancient Douglas DC-3, a twin-engined antique that first flew in 1945. The only upgrade: skis mounted on the wheel axles so that it could land on snow as well as tarmac.

Jojo, the court clerk, was our flight attendant. There was a court stenographer, an armed court security officer and the judge, a Woody Allen-esque character with an enormous moustache and wearing an oversized raccoon coat and hat. Mario, our pilot, was a former French navy fighter jockey in a chic blue uniform with no insignia.

The DC-3 lumbered into the air, and we were off on a five-day circuit with stops in Leaf Bay (Tasiujaq), Payne Bay (Kangirsuk) and Povungnituk (Puvirnituq), the largest of the three Inuit communities on the circuit. It would be a long flight (a DC-3’s top speed is 333 km/h) but a happy one; shots were being poured as the ancient flying machine was droning and rattling over the Laurentians. We were well acquainted by the time we crawled past Schefferville. When Jojo began bragging about recent breast-enhancement surgery, her colleagues persuaded her to show everyone on the plane the results.

Seven hours after leaving Montreal, we approached Leaf Bay, a small settlement on the edge of the frozen ocean. Mario put the plane down on what looked from the air like a down pillow. It wasn’t until we were 10 feet off the deck that we could see that the surface had been rough-packed by snowmobiles before re-freezing. The plane lurched and banged to a stop. Snowmobiles roared out onto the ice to greet us and convey the entourage to shore, where the party moved into the local clinic. I woke up on a couch with a terrible hangover, unable to recall how or when I got there.

Next morning, court was convened in the community centre. The proceedings were in English, translated into Inuktitut and back. The halfdozen defendants pleaded guilty to charges mostly involving alcohol, expressed remorse and claimed they didn’t know what got into them. The judge sentenced them to community service, then gave each a fatherly heart-to-heart about the dangers of alcohol. His obvious sincerity was impressive.

Guilty pleas and minor sentences meant none of the accused would accompany us back to Montreal and continue on to a detention centre near Granby. Waterloo was reserved for those whom the court decided should be removed from their community. The village elders generally intervened on behalf of the accused because many of those transported south never came back.

After lunch, we took off for Payne Bay. The liftoff was more violent than the previous day’s landing, with chunks of ice ricochetting off the fuselage. The on-board party resumed.

Payne Bay was slightly larger, but the crimes were similar, with one exception. The son of a village elder stole alcohol, then made a half-hearted attempt at sexually assaulting one of the nurses after breaking into her residence. The judge warned the offender of the horrors of exile to Waterloo. The man looked terrified. We lunched on caribou pot roast before flying out to Puvirnituq.

We boarded our ancient bird and strapped ourselves into our rump-numbing seats while Mario revved up the twin radial engines. One was running rough. We deplaned onto the ice as Mario and a local mechanic ran through the checklist of probable causes and fiddled with the engines before closing the cowlings. Mario decided to take the plane for a test spin. We watched from the ground as he banked into a hard turn, the wingtip just above the ice. He landed, we reboarded and took off for Povirnituq.

POV was the headquarters of the Inuit Tapirisat, one of the driving forces behind regional self-government and the eventual creation of Nunavik. I skipped court and spent the day talking with Tapirisat elders about what autonomy would mean to Quebec Inuit. We headed over to the local eatery for a bite.

“What’s good?” I asked my hosts. They recommended the steak. “What about country food – caribou, bear, seal, whale?” Quebec’s game laws won’t allow it, they explained. It’s a serious offence, with big fines and possible jail time.

Autonomy didn’t arrive for another 32 years with the creation of Nunavik in December 2007.

JIM DUFF began his reporting career at 14 with the weekly Hudson Gazette. For the next 50 years, he has worked in and/or managed public and private radio and television, daily and weekly print. He was one of the hosts on essentialtalk.com, Canada’s pioneering streaming audio network and continues to blog (thousandlashes.ca). He still retains the Quebec rights to the Bloc Québécois name after buying it as a radio publicity stunt in 1998.

IN HIS OWN WORDS: My last job in print was the 10 years I spent as editor of the newspaper where I began. In October 2014, my publisher/spouse/partner Louise Craig and I closed our 65-year-old weekly because neither of us wanted the other to die in the saddle.

I’m a politician now, a municipal councillor in the town where my father once published the Gazette. Former colleagues chuckle because I’ve gone over to the dark side. Political colleagues have given up trying to control my urge to tell taxpayers the truth.

Every newspaper and half the radio stations I worked for are either dead or dying at the hands of the CRTC, Competition Bureau, media monopolies, hedge fund sharks and the complicity of a succession of federal and provincial governments.