Blood and babes were bread and butter

She didn’t have to speak; her expression said it all.

I had told my friend that I’d just landed a job at the Edmonton Sun and I could see that she disapproved. How could I work for such a sexist right-wing rag? That was her view of Sun newspapers and, truth be told, it was mine, too.

My only defence was, sexist right-wing rag or not, I wanted to get back into my chosen profession – working for a daily newspaper – and the Edmonton Sun had come calling. Like most people, copy editors need to feel wanted.

It was 1981 and I was one of hundreds of reporters, photographers and editors who had fanned out across the country looking for employment after becoming collateral damage on Aug. 27, 1980 (Black Wednesday) – a day that will live in infamy in Canadian journalism – when two rival national newspaper chains conspired to limit competition by closing the 94-year-old Ottawa Journal and the 90-year-old Winnipeg Tribune. Thomson Newspapers owned the Journal, where I’d been a reporter, and Southam Inc. owned the Trib. Nothing, of course, came of the national uproar that the closings caused, nor the subsequent Royal Commission looking into ownership concentration of media in Canada.

After a year of toiling at a suburban Toronto weekly I was ready to go west, young man, even if it was only to a job with a Sun tabloid.

Rising out of the ashes of the stodgy Toronto Telegram, another oldtime big-city broadsheet to bite the dust (in 1971), the Toronto Sun shook up T.O. like a stripper at a church bake sale – irreverent British-tab sensibility, shrieking headlines, crime and mayhem, condensed news stories, redneck columnists, Sunday editions (not a Canadian tradition), exhaustive sports coverage and – ta-da! – bodacious babes on Page 3 (also not a Canadian tradition).

She was known as the Sunshine Girl, a euphemism for pin-up, and readers could ogle her in all her buxomness while pretending to be innocently reading a newspaper. And, like her British progenitor, albeit without baring her nipples, the Sunshine Girl would appear unfailingly on Page 3 no matter what the news of the day was – presumably even if World War III broke out.

The upstart Toronto tabloid was an instant hit and before long it spawned little Suns in Alberta. The Edmonton and Calgary versions, following the flagship paper’s winning formula of sensational headlines, crime and gore, endless jock talk and daily excoriations of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, bilingualism and the metric system, also dished out dollops of Western alienation. And, of course, there were Sunshine Girls in various states of undress on Page 3, and in the flesh – with fishnet stockings and scarlet tailcoats – at publicity events.

Looking back from the perspective of 35 years later, I’m sure my ambivalence about joining the Sun had more to do with its troglodyte politics than its frat-boy world view. After all, sexism was as ubiquitous in the 1980s as cigarette smoking and drinking and driving. Back then, no one would think anything of a small-town weekly referring to female school basketball players as comely cagers, and a photo caption from my Ottawa Journal days said motorists could be forgiven for not noticing the stop signs being wielded by 19-year-old twins working on a road crew in shorts, tank tops and construction helmets. The headline: “Eye Stop-hers.” Uh-huh.

But the Sun boldly took male chauvinism to a new level.

Alberta-bound, I knew what I was getting into, and it wasn’t the New York Times or Le Monde.

I got my first taste of Fleet Street on the Prairies when, after motoring across the flatlands from Saskatoon, I was shown around the Sun newsroom, which was in a suburban office building near an oil refinery. I was invited to sit in on the 4:30 p.m. news meeting.

The sun might have set on the British Empire, but to my small-town Canadian ears I got the impression that day that British influence on Canadian newspapers was far from setting at the Sun.

“Well,” the Brit city editor said to the Brit editor-in-chief, “we could go with the murder of the Sunshine Girl, or there’s the guy who got his brains bashed out with a hammer. It’s a pretty good one, brains hanging out all over the place. Decent stuff.”

Whatever my misgivings were about joining the Sun, and sense of guilt by association, I soon started to feel at home with my fellow copy editors, a motley posse of transplants from Britain, the U.S. and central Canada, plus a homesick Maritimer. We banded together that bone-chilling winter like exiles stranded in a windblown weather station in Antarctica.

At work each night, seated behind visual display terminals, as we called them in those days, encircling the slot person who quarterbacked the next day’s edition, my fellow “rim rats” – a.k.a. “rim pigs” – and I would massage, pummel and hack local copy and wire stories and tried to outdo each other with the wittiest headlines we could conjure up.

Despite unrelenting deadline pressures there was no shortage of banter on the rim, and it often morphed into mirthful mockery of the Sun’s barnacle-encrusted columnists, their unflagging cheerleading for the oil industry and bare-knuckle capitalism and their frothing denunciations of what they saw as effete eastern liberals. We especially delighted in lampooning Toronto-based columnists like Czech-born Lubor J. Zink, whose anti-communist paranoia would make Joseph McCarthy sound like a pinko, and British-born socialite Barbara Amiel, whose haughtiness would make Marie Antoinette look like Mother Teresa.

I’m sure our scorn for Babs would have been even more savage had we known that she’d become Baroness Black of Crossharbour after marrying blowhard tycoon and felon-to-be Conrad Black, husband No. 4, a decade later.

Our ancillary tasks included concocting Sunshine Girl captions, based on the snippets of biographical data provided to us by photographers, who each night sashayed young women past us to their studio. “Debbie, 19, is into dreamy hunks and fast cars. VROOM! VROOM! Chief turnoffs: thermonuclear war and guys who come on too strong.”

Once, after a young woman had been paraded by, a trio of editors stood and held up sheets of paper with hand-written scores – 9, 7, 8½ – like Olympic figure-skating judges.

Another of our duties was crafting the Bill Oddly column.

Each shift one of us was designated to cobble together the quirkiest news stories available on our wire services and add sardonic comments by the aptly named Mr. Oddly. Regular readers of the column must have been puzzled by how Bill’s tone and voice could change so drastically from day to day, depending on which copy editor had donned his persona the night before. Sometimes using words like lasses, lads, pints and bollocks, Bill sounded like a Brit who’d filed his column from a pub in Bristol; other times you’d swear he was a good ol’ boy holed up in a fleabag motel on Route 66. Despite the fact that Bill didn’t exist, he and the missus received a steady flow of invitations to local social events, to which the Sun would dutifully respond by saying that Bill was on assignment.

But blood and guts were our bread and butter and we packed our news pages with it.

Peter Stockland, a reporter, recalls leading off a story with – “Blood stained a skid row sidewalk yesterday after an attack by a knife-wielding maniac” – and getting a standing ovation from the news desk because editors had been desperate for a lead story.

“I might have added ‘brazen’ and ‘daylight’ just to jazz it up,” he says. “It was actually a bullshit fight between two drunks on Boyle Street, but it did the trick.”

On one typical night on the rim a photographer and reporter returned from covering a train-truck collision. Managing editor Randy McDonald looked up from his VDT and asked: “Anyone killed?”

“Nah,” the photographer replied.

“Was it a miracle?”

And that, in a nutshell, was the Sun’s approach to news:

CARNAGE!

Dozens die in crash

Or:

MIRACLE!

Dozens narrowly escape death

It needed to be one or the other.

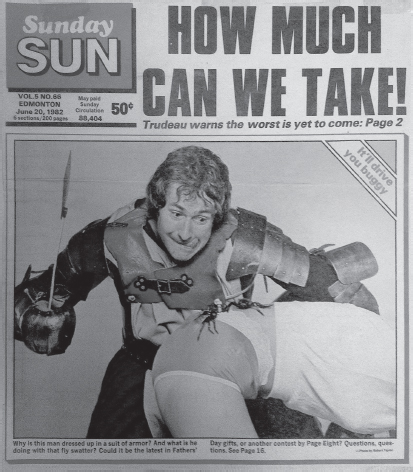

Sun banner headlines were all in capital letters, never understated, often garnished with an exclamation mark, and in a type size that newspapers in earlier times reserved for more earth-shaking stories (e.g. GERMANY SURRENDERS or JFK ASSASSINATED). Above or below the main heading would be a deck explaining what the story was actually about:

CHILE ON THE BOIL

Protesters take to the streets of Santiago

In 1982 when populist Calgary Mayor Ralph Klein delivered his infamous “Eastern bums and creeps” speech in which he blamed newcomers for a spike in crime in the city, news editor Tony McAuley came up with, in tiny type, “Ralph to East” followed by the 120-point screamer: “BEAT IT, CREEPS.” He was proud of that one.

Copy editors were urged to whip up snappy, sexy headlines, so it came as a bit of a shock when I discovered that there were limits. That was the time my boss had me redo my MR. FIX-IT FIXED headline over a story about a man who’d accidentally amputated his penis with a saw in his basement. I figured it was acceptable because, well, the story had a satisfactory outcome – the hapless handyman had his severed member reattached thanks to a surgical breakthrough. Also, he was unlikely to ever see my headline because he lived in the U.S. Midwest, far from Edmonton and long before one even imagined newspaper stories appearing online. Miffed that my brilliance would be seen only by readers of the first edition, I trudged back to the newsroom from La Petite France, the Sun’s smoke-filled, after-hours watering hole, to replace the headline with something more prosaic.

“At least you didn’t go with Black & Dicker,” quipped city editor Graham Dalziel.

I’ve often wondered what readers would think if they could hear the guffaws generated in newsrooms by stories like that of the unfortunate Mr. Fix-it. Maybe it’s just our way of coping with human misery – laughter – but there have been times when it’s given me pause. For example, after a 10-year-old boy had presumably drowned after being sucked into the city’s sewer system when a manhole cover was forced out of position by rising water, a Sun manager asked the city editor if there were any updates on the “sewer rat.”

Then there was the night that a wire story moved telling us that Barney Clark, the first human recipient of a permanent artificial heart, had died – or, in newsroom parlance, “assumed room temperature.”

“Shit!” the slot guy said. “That blankety-blank would have to die.”

Actually, on that occasion I was most surprised by my colleague’s milquetoast “blankety-blank” reaction given that our deadline was fast approaching, we were feverishly working on a story about five people killed in a train wreck near Calgary and there was no time to shoehorn in “the formerly alive” Mr. Clark.

As with MR. FIX-IT FIXED – “play it straight,” I was told – those of us on the rim were never sure what the Sun brain trust feared would offend readers. This we blamed on what seemed to be a behind-the-scenes tug-of-war of likes and dislikes between editor-in-chief David Bailey and Patrick Harden, who was on his way to being promoted from general manager to publisher. It was said of Bailey, an Englishman with a bushy beard, that he worked hard and played hard, and that he liked to push the envelope, “but never beyond acceptable Canadian standards.” On the other side was Harden and his Boy Scout-master earnestness, which seemed far removed from whatever our sassy and brassy little paper was supposed to be.

“The Harden days were the worst,” recalls Ric Littlemore, a good-natured news editor whose beloved Jaguar we referred to as The Dildo on Wheels.

“I stuck a stupid story in one day about some Québécois teens whose friend had just died,” Littlemore says. “After the service in the cemetery, but before the help lowered the casket, the kids cracked it open, sat their friend up and put a beer in his hand, and then proceeded to get drunk with him one more time. Cops put a stop to it. I loved the story. It came in late and I had this perfect, if too-prominent little (news) hole.”

The next day, “Harden came in screaming: ‘What were you thinking?’”

Littlemore tried to tell him that he thought it was “an interesting contemplation on youthful reaction to death,” to which Harden said it was just the kind of thing to further trash the paper’s shabby reputation. “It’s stories like this that will make people stand right up and throw the paper into the garbage.”

“Oh, c’mon,” Littlemore protested, “no one would do that.”

Harden replied that his wife had done that very thing at the breakfast table.

“He had to read his own paper with coffee grounds falling onto his pressed white shirt,” Littlemore says.

So a story about teens’ beery sendoff of a departed friend was deemed too edgy but for a hike in transit fares? Have a girl in a bikini boarding a city bus.

Objectifying women on our pages was one thing, but even by the politically incorrect Zeitgeist of the early ’80s, the appearance of a stripper in our newsroom came perilously close to crossing a line.

The stripper, who appeared to be stoned, had been hired by a couple of madcap colleagues to perform a lap dance on reporter Peter Stockland in honour of his approaching nuptials. She started the music on her boom box, disrobed and plunked herself on Stockland, who squirmed and smiled broadly. Female staffers fled the newsroom. The window that separated our fishbowl of a newsroom from the office building’s atrium was soon plastered with the faces of civil servants and businessmen in shirts and ties, feasting their eyes on the tawdry show unfolding inside. The peeping Toms quickly vanished, however, the moment a Sun photographer began snapping pictures of them.

Our nondescript newsroom was frequently the scene of another sort of spectacle whenever entertainment editor Dave Billington came storming in in high dudgeon over some perceived injustice, hurling insults around like hand grenades. (“So, you little Nazi, shouldn’t you be out running around in lederhosen?”)

Billington’s broadsides, I came to learn, were just his way of getting the creative juices flowing. After heaping abuse on one of us, or someone not in our presence – once, for some long-forgotten reason, on environmental guru David Suzuki, Billington would quietly take his seat, extend his fingers over the keyboard as though he was about to perform a Rachmaninov piano concerto, and knock out an absorbing review in about 15 minutes.

He was a tall, gruff man’s man who wore a ponytail, baseball cap and fleur-de-lys medallion (symbolizing his affection for the Québécois). His T-shirt stretched over an impressive paunch which was largely the product of years of familiarity with Jack Daniel’s.

Billington had worked for Reuters in London before capturing a couple of National Newspaper Awards for critical writing while at the Montreal Gazette (in 1972 for a review of Rudolf Nureyev and a year later for a column about Marlene Dietrich). He then fulfilled a life-long dream of becoming a cowboy by working as a ranch hand in southern Alberta for a couple of years, before climbing back into the arts-writing saddle. It was while at the Sun that he added rodeo reporting to his repertoire, an unlikely field of expertise for an arts writer. When the rodeo came to town, Billington dressed the part, doffing his ball cap in favour of a Stetson.

Despite his rough-and-tumble appearance, Billington brought a touch of eloquence to the lowbrow Sun.

My favourite memories of him were when, after work, I’d arrive at La Petite France and he’d be sitting at the bar with his foot on a stool, presumably reserving it for me. His newsroom bluster would be gone, and we’d talk. Well, mostly he’d talk – sometimes recounting old war stories like about the time he got drunk on bourbon with John Wayne – and I’d listen.

Alcoholism has long been an occupational hazard in the news business and during my first few months in Edmonton, still the most brutally cold winter I’ve experienced in my 70 orbits of the sun, it dawned on me that my life had essentially been reduced to sleeping, working and quaffing beer, and not necessarily in that order. La Petite France had become my second home. I needed a healthier modus vivendi, but instead of reducing my beer consumption I opted instead to cut back on sleep – I was in my early 30s and could get away with it – and took up distance running.

To avoid the bitterly cold, lung-searing winds of March, I began my running regimen on the indoor track at the Kinsmen Field House. Around and around I’d go, almost in a trance, a little more each day, and always to the high-pitched sounds of Supertramp’s Breakfast in America, the only tape the sports facility had.

Edmonton (a.k.a. The City of Champions) has long been a great sports town – whether you were running marathons, etc., or a spectator. In football, the Eskimos dynasty rolled to its fifth straight Grey Cup title in 1982, and in hockey the Oilers were emerging as one of the most explosive teams ever, about to capture five Stanley Cups in seven years. Led by scoring sensation Wayne Gretzky, dubbed “Mr. Waynederful” by colleague Tony McAuley, the Oilers put the Oilberta capital on the map, even more so than did the West Edmonton Mall, the world’s largest shopping centre, which opened just before my arrival in 1981.

It was during the Stanley Cup finals in 1983 that the Sun set its sights on New York Islanders’ slash-happy goalie Billy Smith. The Sun’s frontpage consisted of a headline branding the nefarious netminder PUBLIC ENEMY NO. 1 and a close-up photo of a human eye. The idea was that fans would take their copies of the Sun to the game, hold them up, and thereby unnerve Smith with thousands of evil eyes looking at him.

“This’ll be great,” a manager enthused when it was suggested what a marketing coup it would be if the Hockey Night in Canada TV broadcast were to show the Sun’s front page.

And it might have worked had it not been for the fact that the photo, if turned sideways, looked more like a giant vagina than an eye.

I never intended to become a Sun lifer. Montreal and its charms were calling, so I left Edmonton after only two and a half years, a small fraction of my 38½ years in the newspaper business.

Sure, the Sun was a sexist right-wing rag. Still is, I assume.

But it was a fun place to work.

JIM WITHERS is a pun-loving retired newspaperman who once spent Thanksgiving in Turkey.