To err is human, but to really screw up you need to work for a newspaper.

Or at least you did.

Before the world truly became a global village, with everyone drowning in a continuous tsunami of information – and misinformation – there was a time when people relied on the news to arrive once a day, in paper form, put together by copy editors like me, to be digested with your morning coffee. It was a daily miracle, when not only did words matter, but so did facts, when those of us involved in the dissemination of news were as concerned about getting stuff right as we were about getting it out.

And how mortified we were when we didn’t get things right.

Take DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN, the infamous Chicago Daily Tribune front-page headline that erroneously proclaimed Thomas Dewey victorious over Harry Truman in the 1948 U.S. presidential election. I can imagine colleagues telling the poor schmo (or schmoes) who were responsible: “Look, no one died” or “Don’t feel bad, tomorrow it’ll be lining a birdcage.”

But a famous photo of a beaming Truman holding up a copy of the mother of all newspaper gaffes, reprinted countless times, belies any comforting thoughts about mistakes ending up in birdcages.

And while it’s unlikely that anyone would die as the result of a copy editor’s blunder, there were times when mistakes took a toll. (“He’ll never live that one down.”) In the days when newspapers really mattered, it took a gaffe to laugh (somebody else’s); it took a typo to cry (your own).

I can still hear the chortling on the Montreal Gazette news desk the day after the editor in charge of seeing off the previous night’s final edition had “fixed” a story and headline about Catholics calling for the beatification of Queen Isabella I of Castile. Apparently not well-versed in Catholicism, he replaced “beatified” with “beautified.”

The fear of making mistakes caused stress, often leading to lost sleep or self-medication. More times than I care to remember I awoke after only a couple of hours of sleep, my mind racing with thoughts that I might have gotten a headline wrong or let something libellous slip through in body type. This would be followed by the agony of waiting another couple of hours to hear the thump of the newspaper landing on my doorstep so I could see if I had, say, typed a suitable headline over the dummy one I’d tapped onto a page when laying it out. Newspaper databases reveal a staggering number of space-holder headlines that appeared in print:

National Post

Oct. 29, 1999

Arts & Life

HEADLINE: Funny film headline goes here

Toronto Star

March 3, 2000

HEADLINE: Powell headline goes here 2 full lines deep;

Deck goes right here and it’s 3 lines deep

And then, when my fears were confirmed, there was the dread of having to face the music. You didn’t want to begin your shift by seeing your cringe-worthy handiwork, along with an acerbic comment, displayed in LOOK IT UP!, a critique of copy editors’ work posted on the bulletin board by Joe Gelmon, the Gazette’s ayatollah of style.

Joe Gelmon was the Montreal Gazette’s ayatollah of style, and his bulletin-board critiques of editing mistakes were often biting.

But worse was being reamed out by managing editor Mel Morris, a white-haired, old-school newsman with an infallible bullshit-detector, an uncanny ability to see holes in news stories and a reassuring decisiveness when it came to selecting the day’s lead story. His face, when he was about to blow his top, was like a thermometer; you could see the redness rising. (“And then all Mel broke loose …”)

For some deep-seated, masochistic reason I’ve kept a memo he left in my mail slot in 1987:

“I suppose it’s possible to make more mistakes in a single headline, but I hope I don’t live to see it …”

And that was the gentle part.

I’d misspelled “violinist” – omitting the third “i” – in a headline over a recital review by our classical music critic and referred to a nine-year-old prodigy as an 11-year-old. I’d whipped up the headline while the reviewer was still writing and hadn’t noticed that he’d changed the prodigy’s age from 11 to nine.

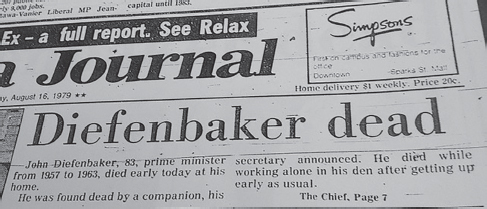

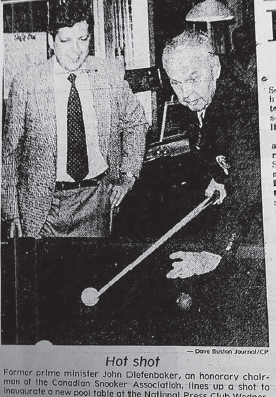

I shudder to think of how Mel might have reacted had he been at another paper where I worked, the Ottawa Journal, on Aug. 16, 1979, the day John Diefenbaker died. Imagine how perplexed readers of that now-defunct paper must have been after reading about Diefenbaker’s death on the front page, only to turn to Page 4 and find a photo of Canada’s 13th prime minister looking very much alive, with a pool cue in hand no less. (Only hours before he died, Diefenbaker had inaugurated a new pool table at the National Press Club.) The Journal was an afternoon paper, and several inside pages were put to bed the night before they were to appear in print. Whoever laid out the front page on the morning of Aug. 16 was, obviously, unaware of what was on Page 4.

The front page of the Ottawa Journal announces on Aug. 16, 1979, the death of former prime minister John Diefenbaker …

… while three pages later a photo shows Diefenbaker very much alive, shooting pool.

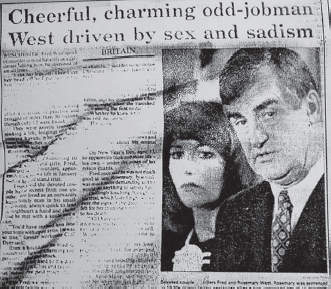

Another colossal gaffe involving a picture of a Canadian politician was made by the South China Morning Post, an English-language daily based in Hong Kong, when in 1995 it published a photo of Lucien Bouchard and his then-wife Audrey Best under a story headed “Cheerful, charming odd-jobman West driven by sex and sadism.” Somehow the Morning Post mistook Bouchard and Best for Fred and Rosemary West, two British mass murderers.

Oops! The South China Morning Post, an English-language daily based in Hong Kong, somehow mistook Lucien Bouchard and his then-wife Audrey Best with a pair of British mass murderers.

One of the most celebrated blunders in my early years at the Montreal Gazette occurred because of the fact that, in the 1980s, copy editors were not permitted to typeset corrections for stories already pasted onto pages. Instead, this had to be done by members of the printers’ union, many of whom were francophones and less than proficient in English. On this occasion, between first and second editions, a copy editor wanted to fix an incorrect date in a story about a fatal car accident. The date got fixed all right, but in the process the typist botched the rest of the sentence and “fiery car crash” became “fiery car wash.”

Also getting LOOK IT UP! bulletin-board treatment was a sentence in a landlord-tenant column containing this: “… the previous owner, now deceased and unavailable for comment …”

In those days, Gazette copy editors did page layouts by hand, rolling them up and firing them off in clear-plastic cylinders through a pneumatic tube to the composing department. There, compositors would wax and cut the strips of type we sent them. Then, following our layouts, they’d place the strips onto pages. It was often an adventure, especially when Pierre, a madman with an X-Acto knife, was handling a page. Once, on deadline, when my layout called for a headshot of singer-actress Dolly Parton, I discovered that Pierre had lopped off Parton’s forehead, but instead squeezed in her ample breasts.

But the comps were gone or re-assigned in the early ’90s, thanks to the arrival of pagination, a process which allowed editors to put pages together electronically. And while my copy-editing colleagues welcomed the control the new system gave us, I found it a mixed blessing. Pagination just gave me new ways to screw up royally, which is exactly what I did – literally – when I somehow juxtaposed captions for a photo of a World War II concentration camp and a painting by Prince Charles.

But there’s no stopping progress. When the Gazette installed Tansa Systems around 2010, the new spell-check software had the unfortunate habit of, every once in a while, changing words like Habs – a headline-friendly moniker for the Montreal Canadiens hockey team – into Hats. At least once Hats appeared in a headline on a Habs story. Go Hats!

I marvel at how bright the young people coming into the multi-faceted news business are, and the ease at which they master 21st-century technology. More power to them. But I didn’t get into newspapers to grapple with the likes of Tansa, which I facetiously claimed was my reason for taking a buyout. “One of us must go,” I declared, a reference to what Oscar Wilde supposedly uttered to the wallpaper while on his deathbed in Paris.

I could have said the same thing about the advent of newspaper “platforms,” when the “print edition” started becoming a mere sideshow to the non-stop digital news cycle.

As a retired newspaperman whose life has straddled two worlds – the one that evolved from Gutenberg’s invention of movable type and the digital one that supplanted it, I confess that my affections are more with the former.

In the pre-search engine days, having good general knowledge was a necessity to copy editing, especially for fact-checking. When that failed, we’d call the Gazette library (a.k.a. morgue), where staffers would do our sleuthing for us by perusing old newspaper clippings.

Frequently fact-checking involved interrogating a reporter by phone after he or she had filed their story and left for home or – say, in columnist Nick Auf der Maur’s case – a bar.

Nick was a Montreal phenomenon in a less politically correct time. With his bushy moustache, beaver-toothed grin, and fedora slightly askew on his head, Nick was a city councillor, radio commentator, filmmaker, man about town and bon vivant who cultivated his notoriety as a boozer and bum-pincher. Never letting facts get in the way of a good story, Nick’s columns were packed with endearing anecdotes and childlike enthusiasms, which I would have enjoyed editing more had they not also been a minefield of typos. To question Nick about his columns I enlisted the help of our switchboard ladies, who knew the drill, and would start calling Ziggy’s, Grumpy’s, Winnie’s or one of his other haunts. Minutes later Nick would be on the line, well-refreshed, shouting over tinkling glasses, women laughing and other sounds of good cheer.

Another moustachioed Gazette writer, police reporter Eddie Collister, also posed challenges for editors. Like Nick, Eddie was a throwback, in his case to the days of hard-boiled detective fiction. With Eddie, the challenge wasn’t so much weeding out typos, but rather trying to decide how much of his Mickey Spillane prose we could let get into the paper:

•“On the Main you can get a steamie for 50 cents, or you can get rubbed out for 50 bucks.”

•“Marion, who took several bullets in the head and was dead before his face landed in his plate of bacon and eggs, was apparently ordered eliminated because he had crossed a friend of a Mafia heavy.” (I’m not sure if this last one made it into print without being toned down, but I hope so.)

Copy editors were people who sweated what other people would probably now view as small stuff – spelling and grammar. We were junkyard dogs trying to fend off abominations like “I could care less.” As quaint as it must seem in this LOL, OMG, abbreviation-crazy age in which colons and semi-colons serve as smiley and winky faces, and an emoji can be named Oxford Dictionary’s “word” of the year, newsroom bunfights used to break out over such issues as the spelling of dyke (or dike).

Joe Gelmon was arbiter of what was acceptable spelling at the Gazette in the 1980s and ’90s, and this involved putting out a style book. It would be an understatement to say that Joe’s rulings were idiosyncratic. For example, the 1990 edition decreed that “sox” would be the plural of “sock.” That, fortunately, quickly got overruled by management. Contrarian that he was, Joe insisted that words like honour, labour and neighbour be spelled without the U, even though other publications across the land were moving back to more traditional Canadian spellings. “Honour,” his style book said, “should be dismissed as a silly regional affectation.” And whenever there was a question as to whether or not a word should be capitalized, Joe advocated what he called the “(Linda) Lovelace” rule: “When in doubt, go down.”

A style directive that we should not use diacritical marks (accents) in names and words other than English or French may have been responsible for at least one embarrassing headline.

Always eager to reach out to the city’s “ethnic communities,” the Montreal Gazette on Dec. 31, 1993, wished its readers HAPPY NEW YEAR in several languages on its front page. Unfortunately, by omitting the tilde over the first N in FELIZ AÑO NUEVO, the message to Hispanic readers was more along the lines of HAPPY NEW ASSHOLE.

Joe was witty in person and print – one of his headlines, over a story about a legal dispute involving a clothing manufacturer, read: “Flap over pants turns into suit” – but he could also be persnickety, perhaps a prerequisite to being a top-notch copy editor. His obsessiveness, however, did occasionally lead to newsroom flare-ups, especially when someone, in his absence, occupied his workstation. He posted a sign on his computer saying: “You are a guest here. Please leave the machine and its settings exactly as you found them. And please don’t leave detritus on the desk.”

Most of Joe’s workstation battles involved editors who occupied his spot during the day while working on “zones” – the weekly neighbourhood sections that were inserted into the main paper – and on one occasion he got hoisted into the air, chair and all, shouting in protest.

With only one weekly deadline to concern themselves with, zone deskers had time to collect some of the Gazette’s funniest raw copy from the young reporters working on the neighbourhood sections:

•“‘I found it moving,’ Rev. Fontaine said after the 10-minute nudists’ wedding ceremony.”

•“Fire Chief Jean-Marie Robert said he had seen the cat in Clark’s apartment fighting the blaze.”

•“Johnson was the only one not wearing a puppy for Remembrance Day.”

But cub reporters weren’t alone in keeping copy editors hopping.

Long-time reporter Alan Hustak, for example, could write well, especially when he could bring in an historical component to his stories, but his inability to spell was legendary. When his typos were pointed out, Alan would cheerfully quote Ralph Waldo Emerson: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Or simply say: “That’s why we have editors.”

Indeed, we still have editors. At least for now.

RIP, President Dewey.

JIM WITHERS is a retired newspaperman who can never order anything in a restaurant until he’s found at least one typo on the menu.